The Olympics Are in Tokyo, Is Team Japan Poised to Beat Everyone?

Olympic team member Akiyo Noguchi has been a dominant force for over a decade, with 21 World Cup competition victories. She placed fourth in the Meiringen, Switzerland, Bouldering World Cup in April. (Photo: Daniel Gajda/IFSC)

This article was published in the summer edition of Gym Climber, available free at your local climbing gym.

During the final round of the Bouldering World Cup competition in Eindhoven, Netherlands, in 2011, Akiyo Noguchi eased into a toe-hook on an overhanging volume, gripped a faraway sloper, cut her feet briefly and then cruised to the top. Noguchi would finish the round with all boulders topped to claim a victory over Austria’s Anna Stöhr—at the time the legend-to-beat in the women’s division on the circuit. But it was not just Noguchi’s eventual win in a stacked field that garnered attention; it was her climbing style, and the fluidity and assuredness with which she progressed through the pulse-quickening round. “Akiyo Noguchi of Japan shows some great athleticism as she climbs her way to victory,” one of the commentators effused as Noguchi stabilized herself in that particular boulder’s tricky overhanging toe-hook. “Akiyo’s consistency and few attempts clinch the title here.”

Also read: Olympic Climbing Schedule, Dates and Times to Watch

Noguchi had just turned 21 at the time of that Eindhoven World Cup competition, and news of climbing’s inclusion in the Olympics was still years away. However, Noguchi had already established herself as a formidable presence on the international scene, having won previous World Cup events in Canmore, Canada, in 2011; Wien, Austria, in 2010; and Kazo, Japan, in 2009, to name a few. In doing so, Noguchi had managed to keep her home country of Japan as a mainstay in IFSC event finals, largely picking up where Japan’s previous competition superstar, Yuji Hirayama, left off in the 1990s.

Go here: To meet the teams from the United States, Japan, Slovenia and the Czech Republic.

Yet, upon reflection and irradiated now by the glow of the forthcoming Tokyo Olympics, where climbing will finally debut, Noguchi was doing something else during her initial years on the IFSC circuit: She was heralding the dominance of an entire national team, and summoning the company of many Japanese compatriots who would soon join her at the elite level.

Also read: The Idiot’s Guide to Olympic Climbing

A Team Forms

Noguchi would eventually qualify for the Tokyo Olympics by placing second at the 2019 World Championships in Hachioji, Japan; this accomplishment, as a culmination of years she spent as Team Japan’s figurehead on the international circuit, was bolstered by 21 total World Cup competition victories and a quartet of overall bouldering season titles. But just three places below Noguchi in the final standings at those same World Championships was Miho Nonaka, who also earned an Olympic berth. In a suitable Olympic narrative, Nonaka had become the intriguing complement to Noguchi, their climbing styles as aesthetically different as their backgrounds. Eight years younger than Noguchi, Nonaka was a pure power climber and the product of the Tokyo gym scene, while Noguchi hailed from a rural farm and climbed on top of cows for recreation before she ever scaled a gym wall. Also, Noguchi had been consistent on the international scene practically ever since that commentary at Eindhoven explicitly stated so in 2011, whereas Nonaka’s presence was more intermittent. Most notably, Nonaka won the overall bouldering season title in 2018 right before shoulder injuries forced her off the circuit for approximately a year.

As a result, anticipation has mounted for the Tokyo Olympics to mark Nonaka’s full return to elite form. Or perhaps the upcoming Olympics will serve as Noguchi’s crowning achievement before a preplanned retirement. Or maybe the Olympics will manage to showcase both of them with a pair of medals in the women’s division for Team Japan.

Japan’s Olympians in the men’s division offer intriguing complements as well. Tomoa Narasaki and Kai Harada also clinched their Olympic berths at those 2019 World Championships. The duo’s Olympic inclusion was fitting considering the two men had traded bouldering World Championships dating back to 2016. And while Narasaki solidified a competition climbing legacy by innovating in the Speed discipline—omitting the third foothold jib to establish new standard beta called the “Tomoa Skip”—Harada occasionally beat Narasaki at speed events (such as the Speed World Cup in Wujiang, China, in 2019).

As part of a panorama, the consistent promise and prominence of Japan’s top competitors on the World Cup circuit over the past few years aligns nicely with the fact that the Olympics will take place in Japan. No other national team has been as consistently dominant over the past 10 years as Team Japan, so there is no better place for competition climbing to have such a high-profile Olympic premier.

Lost in the Olympic narrative is how many competitors on Japan’s national team almost qualified.

Climbing Becomes the Craze

Noguchi, Nonaka, Narasaki, and Harada have received most of their nation’s press and attention as the Olympics draw near. Lost in the Olympic narrative, however, is how many competitors on Japan’s national team almost qualified. For example, also in the finals at those 2019 World Championships in Hachioji—and narrowly missing out on Olympic berths—were Meichi Narasaki, Kokoro Fujii, Ai Mori, and Futaba Ito. The 2019 World Cup season also saw Keita Dohi, Yuki Hada, Natsuki Tanii, Aika Tajima, Mei Kotake, Natsumi Hirano, and Mao Nakamura advance to the final rounds of various events. These additional names added to any ensuing conversation about precisely who the best competitors on Japan’s robust national team might be.

Team Japan’s depth throughout 2019 was so impressive that it formed the basis for a lawsuit by Japan’s climbing federation, the Japan Mountaineering and Sport Climbing Association (JMSCA), which argued that Japan should be allowed to vie for Olympic berths at multiple qualification events—even after the country’s Olympic quota had been filled at a single event. The lawsuit was eventually dismissed by a court of arbitration, but it inadvertently shined a bright spotlight on the surfeit of top-tier competitors under the auspices and oversight of the JMSCA.

Read The Tokyo Olympics Will Be Akiyo Noguchi’s First … and Last

When trying to trace just how and why the JMSCA developed such an abundance of elite talent, you encounter cultural and environmental factors. The assistant coach of Team Japan, Takako Hoshi, points out that a Japanese concept of kaizen—which literally means “to improve”—is utilized as equally in streamlining manufacturing processes in Japan as it is in climbing gyms. “In Japan, we have this culture that we have to constantly, continuously improve,” Hoshi has stated in the past. “It’s in our culture to do that.”

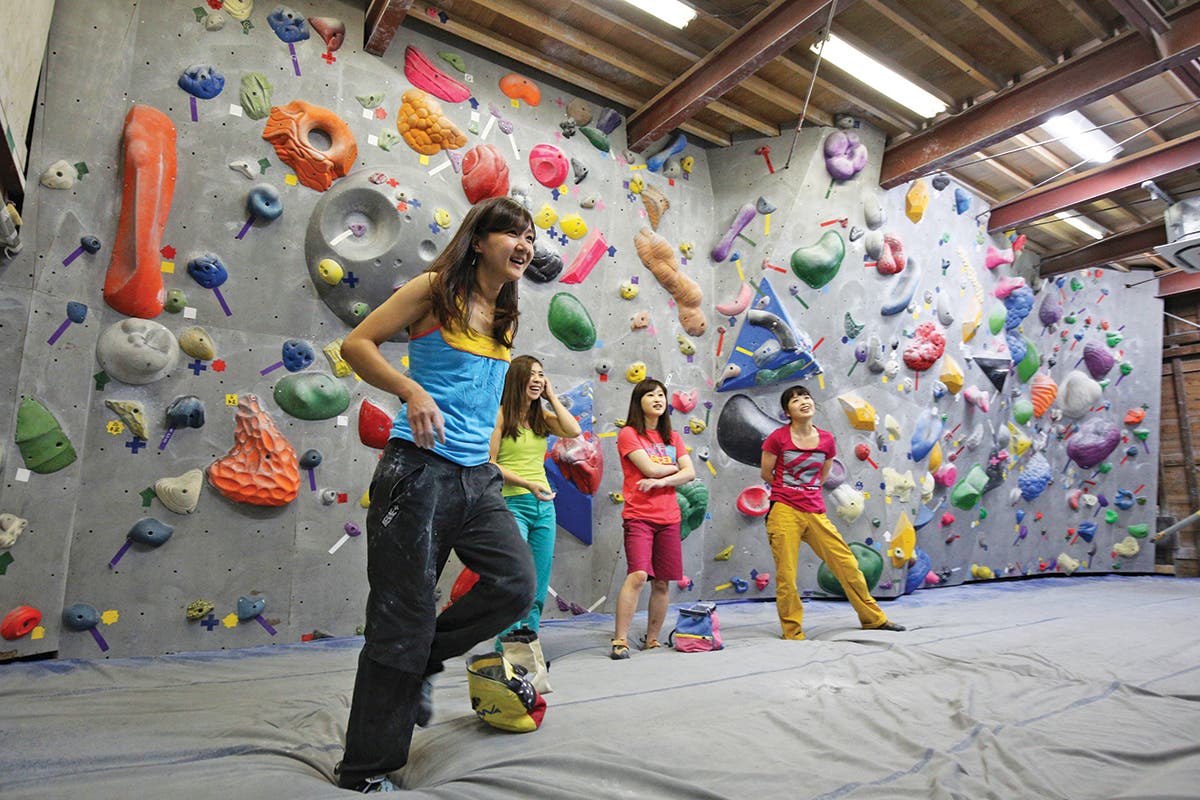

But any systematic adherence to improvement, although relevant, does not make Japan unique among countries represented on the World Cup circuit. Closely coupled with that kaizen concept in training is a climbing-gym scene that is far more concentrated than almost anywhere else in the world. Hoshi once estimated that there were 400 climbing gyms in Japan; if that same concentration were to be applied to the United States, there would be approximately 10,000 gyms here instead of, according to Climbing Business Journal, the 538 that currently exist.

This gym surplus in Japan means that climbing is in the midst of its own boom period in the country, paralleling the Olympic hype and resplendency. And with that, a Japanese domestic climbing industry has been allowed to thrive. As an illustration, in 2015, when Kazuma and Saari Watanabe founded Ziprock Climbing Gym in Fukuoka, they quickly observed climbing’s rapidly increasing popularity. They decided to expand their business, and began creating homemade climbing products, which eventually grew into an entirely new company called Mudhand. Today, Mudhand makes everything from chalk buckets to climbing pants and shirts, and is one of the most popular domestic Japanese climbing brands. “Of course, the Olympics have had a positive impact on us,” Kazuma says.

Kazuma thinks the atmosphere within Japan’s climbing gyms has played a role in establishing such depth at the elite level. He notes that Japan’s climbing gyms are typically smaller than the full-service facilities common in other countries such as the United States, and such close quarters often prompt highly collaborative group climbing sessions. Japan’s gyms often focus solely on bouldering and feature a lot of spray walls. “We do a session called dojo several times a week,” Kazuma says, speaking of the communal climbing on spray walls that is common in many Japanese gyms. “We do not set routes: We just improvise on the spray wall, and bouldering problems get made—I think of this as one element of Japanese climbing culture.”

Shota Uokiri, CEO of Bouldering Gym Share, a 4,000-square-foot gym in Yokohama, says that the profusion of gyms in relatively close proximity throughout Japan’s urban areas has also given rise to a specific type of climber—one who “circuits” the climbing gyms in a given region, visiting as many as possible in a short period of time before starting the “circuit” all over again. “I believe that the ‘circuit’ climbers contribute to [gym] improvements and the quality of the routesetting as well—since we’re always trying to better our routes to attract them,” Uokiri says.

Also read: Who’s Who: Meet Olympic Teams Austria, Great Britain, Germany, France and Canada

Also read: What You Need to Know About the Olympic Climbing Wall

Also read: The Complete Guide to Olympic and World Cup Speed Climbing

Also read: Team USA’s Secret Weapon: Head Coach Josh Larson

Also read: How Team ABC Built Two Olympic Climbers Brooke Raboutou and Colin Duffy

Also read: Olympic Wildcard Colin Duffy May Be the Youngest Climbing Competitor—and the Spoiler

Pandemic postponement allowed members of Team Japan to improve.

“Japanese climbers are enthusiastic,” says Katsu Miyazawa, the director of B-Pump, one of Japan’s most well-known and longest-operating gyms, with facility locations in Akihabara and Ogikubo. “They know the name of holds, brands, and moves very well—not only adult climbers, but also kid climbers. I’ve heard kids talk about a problem with ‘Flathold’s volumes’ and ‘Cheeta’s holds.’ I’ve only heard kids talk like that in Japan.” Miyazawa says that B-Pump is one of the few gyms anywhere that makes a point to set exclusively competition-style boulders—very difficult and highly technical. “A lot of climbers actually visit us from all over the world to try high-quality problems,” he says.

The Stars Align for Tokyo

Even with such a robust domestic scene as a foundation, and with such unparalleled national depth, the current state of Team Japan will largely be gauged by how its four Olympians perform in the Combined format of the Olympics this summer.

To that point, one of the most intriguing developments of the Tokyo Olympics’ COVID-19 pandemic postponement period was how members of Team Japan improved, particularly in disciplines that were not their specialties. At the country’s national championship, the Japan Cup, in March, 2021, Tomoa Narasaki clocked a run of 5.790 seconds in his first speed-climbing heat of the finals, and followed that up with a run of 5.727. Not only were these times approximately one second faster than his previous personal best times, but the run of 5.727 seconds was only .25 seconds off Iranian climber Reza Alipour’s world record.

Akiyo Noguchi, too, surprised many fans and pundits by winning the speed-climbing portion of the Japan Cup. She also placed second in the Japan Cup’s lead climbing.

In a year when most international competitions were canceled—or limited to whittled rosters as a result of the pandemic’s travel restrictions—any national results have become the main indicators of competitors’ developmental progress in all disciplines. The Japanese press’s continued coverage of climbing, as the country’s de rigueur sport, even during the pandemic, has piqued the nation’s interest in the various competitors’ progress. “I feel that climbing has gained a lot of recognition through the media appearances of the athletes,” says Miyazawa at B-Pump. The Tokyo Olympics loom on the horizon as an opportunity for all Japan’s climbing components to come together—the four Olympians representing a much larger talent pool, and their progress signifying a greater climbing-cultural focus on collective improvement as a means for individual triumph.

Predictions for Medals

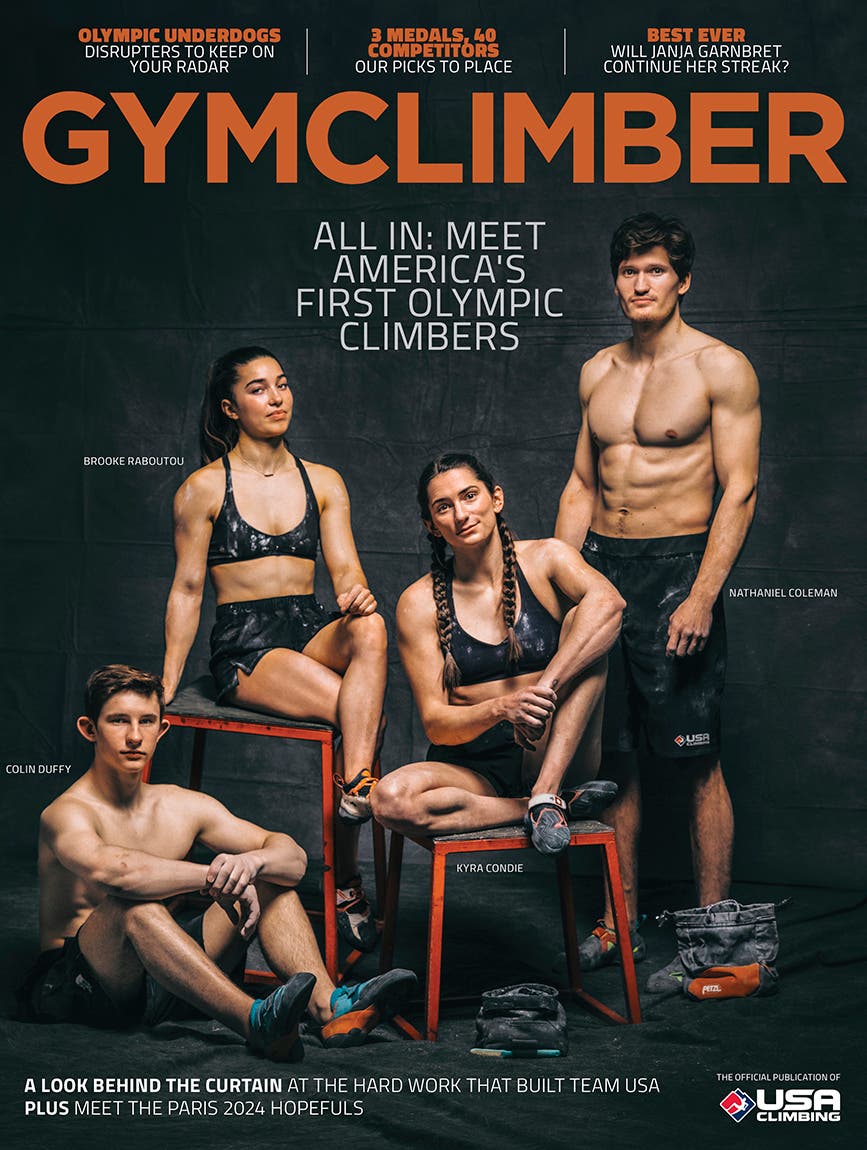

The recent gains made by Japan’s Akiyo Noguchi in speed climbing make her a solid pick for the silver medal. And let’s get nationalistic and say that someone from Team USA will earn the bronze: Brooke Raboutou was the first American to qualify for the Olympics, but Kyra Condie has won the American Combined Invitational. That makes this a pick ’em situation.

The men’s division does not have a clear favorite for the gold, but Japan’s Tomoa Narasaki won the Combined discipline at the 2019 World Championships and has steadily improved at all disciplines. Expect him to look stellar through the Olympics’ speed climbing and bouldering portions. If he can avoid any low falls or slips in the lead portion, he can win.

Let’s foresee an American man earning the silver medal. Colin Duffy, the 2020 Pan-American champion, could shock the world. But since Duffy is only 17 years old, his big Olympic moment will likely come at a later Olympics and the edge goes to the veteran Coleman. And Austria’s Jakob Schubert could earn the bronze to round out the men’s podium.

Of course, keep in mind that part of the fun of making predictions is watching them fall apart. No matter who earns the medals, climbing at the Olympics this summer will surely be a phenomenal show.

John Burgman lived in South Korea for five years, during which time he traveled to Japan on numerous occasions. He is the author of High Drama: The Rise, Fall, and Rebirth of American Competition Climbing.