The Secret to Team USA: Olympic Climbing Head Coach Josh Larson

(Photo: Jess Talley/Louder Than 11)

This article was published in the summer edition of Gym Climber, available for free at your local climbing gym.

It is early morning in Salt Lake City and a chill still lingers in the air of the training center—a reclaimed warehouse known as the “TC.”

Josh Larson, the head coach of Team USA and for the Olympic team, quickly punches in a key code and leads me through the side door as he hobbles forward on his crutches, clanking and clattering over the concrete floor. He broke his foot the week before by missing the pads outside at Ibex, a bouldering area near Delta, Utah.

Pausing for a moment, he cranks up the heat and turns on the lights. As the bay bulbs flicker on, Josh sits down cross-legged and says nothing as I scan a 100-foot-wide spray wall wrapping the room in front of us. It has every angle you could ask for and each square foot is littered with a perfect selection of holds.

ALSO READ A DAY IN THE COACHING LIFE OF JOSH LARSON

“What would make you come to the TC and never have to leave?” Josh asks rhetorically, breaking the silence. “That’s how we started thinking about the build. These walls are specifically based on Dai Koyamada’s gym, the Project—a famous climbing gym in Japan that many U.S. competitors revere.

The tour continues. Deeper inside the facility is another room full of plywood walls ranging from slab to vert to overhang—a variety of angles designed to mimic sections typically found at international competitions. These walls are either blank, awaiting the next round of intricately calculated problems, or sparsely populated with coordination combos, complex power sequences, and high-risk balance moves.

Later, on the way out, I run my hand across a white sheet of plastic hanging from the ceiling. “What’s up with the plastic room?” I ask, my anticipation for the upcoming week of mock comp setting already brimming. “Looks like something from Breaking Bad.”

“It’s so the athletes can train in heat and humidity—a Tokyo simulation,” replies Josh. Inside the enclosure is a custom Grasshopper Board that Josh collaborated on with Jared Roth and Ben Moon. “We are looking for blood, sweat, and tears in there.”

So what experiences and forces in the life of Josh Larson have prepared him for this role—the head coach of Team USA at its inaugural home base—in this moment, as climbing prepares for its debut in the Olympic Games?

Josh Larson has ample competition experience himself—in 2014, he won the Unified Bouldering Championships in Seattle, besting the almighty Jimmy Webb, and went on to place second at Canadian Nationals the same year; in 2015, he finished 3rd at Open Bouldering Nationals—but there’s more to Coach Larson than his former time as a comp climber.

Go here: To meet the teams from the United States, Japan, Slovenia and the Czech Republic.

From the outside, it might look like Josh fell effortlessly into this new role; however, the path that led him here—from rural Massachusetts to the World Cup bouldering circuit to the jungles of Belize—was anything but. Constant change seems to be the only predictable element of Josh’s path. Larson’s fate has always been anchored in climbing the way the roots of a tree are anchored in soil.

He grew up in western Massachusetts in the early 1990s and was slowly exposed to rock climbing. The nearby gneiss boulders and cliffs—tucked away inside the thick forests of the Berkshires—were then only just getting discovered and developed. Life for Josh revolved around other things, like going to church every Wednesday and twice on Sundays, homeschool sessions with his mother all week, and hunting in the woods with his father. As a 10-year-old, Josh sometimes butchered deer for five dollars an hour in the back of a refrigerated trailer. It was not until 1999, during his first time grabbing holds on an artificial wall in Jackson, Wyoming—and firing the hardest route first try—that his parents realized he was a natural at this strange, esoteric sport of climbing.

With no climbing gyms back home in Worcester, Josh decided to set his first problem in the attic with a Metolius starter kit. But after a few weeks, his parents revoked those privileges. “They didn’t want me in the attic anymore because I was breaking sheetrock over the kitchen ceiling,” Josh says, “so I started setting at the local YMCA on a top-rope wall next to the racquetball courts.”

Also read: Olympic Climbing Schedule, Dates and Times to Watch

After several years of dabbling in the sport, Josh climbed in his first Junior Competitive Climbing Association lead competition at Boulder Morty’s in Nashua, New Hampshire, where Vasya Vorotnikov and Kyle McCabe—two locals that would become some of the strongest American climbers of their generation—taught him how to clip a few minutes before competing. Josh tried to use the single-loop harness that he won in Jackson, but since they are not allowed for leading, he had to rent a normal harness.

“I was one of those guys,” he reminisces. “Maybe I still am secretly.”

As a teenager, Josh played baseball competitively, but eventually he let that go and dedicated all his time to the local climbing team. Head Coach, Steve Buck, a guy that could casually send 5.12 in his approach shoes and rip one-arm mono pull-ups, taught Josh the basics of movement.

Through his teens, Josh immersed himself in climbing. But in 2003, at the age of 18, his parents let him know a truth about the world: He needed to find a job and start making a living.

“Being a professional climber at the time was just not a thing,” Josh says regretfully. “I stopped right in my prime.” He started job shadowing as a plumber, then as a construction worker, framing houses. He finally settled on being an electrician, a role in which he “spent the next four years in Boston eating off food trucks and hanging out with a bunch of dirty plumbers in skyscrapers.”

Also read: The Idiot’s Guide to Olympic Climbing

Years later, after buying a house and getting married, things started to fall apart for Josh—something was missing. For the first time in his life, he felt aimless.

“It really all came crashing down at the same time. Like literally—a crash happened,” says Josh, laughing. “I wrecked my four-wheeler in a race, broke my nose, and almost broke my neck. My lungs got bruised by the impact with my ribs from the four-wheeler crushing me into the dirt.” Around the same time, his job called for switching out evaporator fans from the inside of negative 50-degree Costco freezers. After a few months of working 15-minute shifts, in and out of the cold all night long, he quit. A few months later, in 2007, he got divorced and moved back in with his parents.

“I had to figure out what I was going to do with my life,” he says.

With no job, no house, and no marriage, one of Josh’s old electrical apprentices randomly asked him to come climb at Boulder Morty’s over the weekend. Having no intention of picking the sport back up in any meaningful way, Josh joined his friend for what he thought would be a casual outing.

“As soon as I started climbing again that day, everything just clicked,” he says. Vasya Vorotnikov—who had never left—was there the day Josh returned. While Josh had been working on 230-volt, three-phase lighting systems inside a BJ’s Wholesale Club, Vorotnikov had done the first ascent of Jaws II, a 5.15a in Rumney, NH. “I realized that I couldn’t be an electrician anymore,” Josh says. And just like that, climbing came back full force into his life.

About a year after Josh rediscovered climbing, I witnessed him for the first time in his natural habitat during my first-ever bouldering competition at Indoor Ascent in Manchester. He was shirtless, wearing cut-off camo shorts, and screaming like his life depended on it while campusing from one Pusher Boss to another on a 40-degree overhang. I had never seen anyone climb with that kind of raw emotion. When he fell, which was rare, he would get mad enough to make any onlooker feel slightly awkward for watching as he muttered profanities through a clenched jaw—red-faced and fists bound up tighter than the Hulk at his first brawl.

I had never seen anyone climb with that kind of raw emotion.

I didn’t run into Josh for a year after that. The day I really got to know him was the first time he set at MetroRock, in Everett, MA, where I had already been working for a few years. Early one Monday morning in 2009, he stripped an 80-foot-wide by 35-foot-tall section of toprope climbing space with an Allen wrench—a formidable task without the advent of the impact driver—and set 10 routes before I even showed up. I remember thinking that I was either going to get fired that afternoon or end up with a new partner to share the brunt of the workload. Fortunately, his work ethic and genuine psych disrupted my routesetting-induced malaise and we ended up setting together four days a week for years after that.

From discovering and scrubbing new boulders to exploring the seediest of the seedy bars in Boston, we became tight. And when the days got long and our shifts grew menial, like changing out the 18th T-nut of the week from behind the dusty, dank, spider-web laden corners of welded iron and concrete walls, he somehow maintained a cheery disposition in the face of our drudgery.

“Easy money Dave! Keep turning that wrench. Eeeeasy money!” he would yell from behind the wall, precariously positioned in the dark with vice-grips clamped to the misthreaded T-nut while I cranked on it out front with a socket wrench.

Most people know Josh for his playful personality, but few are familiar with his intensely focused and dedicated side. When he had a goal, whether it was a climb or a comp, he would train maniacally for it. Nothing else mattered. While setting and coaching 40 hours a week at the gym, he would somehow manage to train another 20 hours a week, which meant that when I inevitably vanished after work, Josh would stick around for another four hours every weeknight until he was thrashed.

Also read: Who’s Who: Meet Olympic Teams Austria, Great Britain, Germany, France and Canada

He lived to climb and train—most of all, to try hard.

The year he placed third at Bouldering Nationals, he needed a training wall, so he built one. The year we began setting MetroRock’s Dark Horse together, we needed a new wall to showcase the finals problems, so he built one.

“We had zero expectations and limitations to what was possible and even cool at the time,” he says about our days at MetroRock. “We just did what we wanted and it seemed to work out great in the end. That time helped me see that you can do big things in a small place.”

The same attitude that Josh employed back in those years with his setting—and life in general—is still prevalent in his approach today as the head coach of Team USA and in the TC.

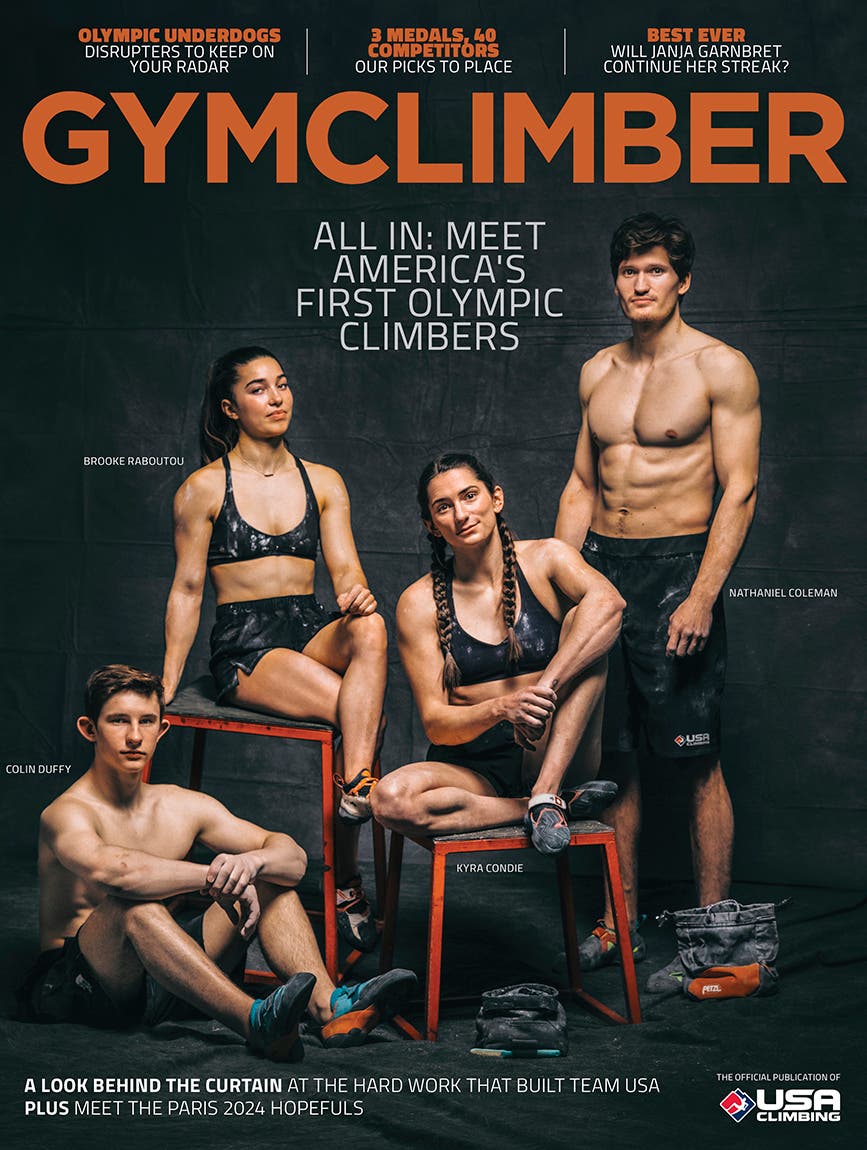

Ultimately though, MetroRock was just the beginning for Josh—it was his runway. Olympic-qualified athlete Nathaniel Coleman says that Josh’s setting “is very applicable to the world stage and since we have the open playground that is the TC, Josh is able to keep me constantly challenged in areas that I’m weakest in. He is unafraid of the absurd, which allows for a lot of nuance and creativity.”

More than climbing hard grades, Josh has always been into discovering and establishing new climbs.

“My happy place is hanging off a rope on the side of an untapped cliff or boulder with no one else around, scrubbing holds, and wondering if it goes,” says Josh, who dedicated multiple seasons to establishing first ascents in Puerto Rico and the Grand Tetons, in addition to several New England classics. “I love new routes and boulders more than sending hard. It’s just never quite the same feeling with a guidebook in my back pocket.”

In 2010, to fund a climbing trip across the country, he started a production company called Cold House Media with Vince Schaefer and Charlotte Durif—a French climber with a PhD in material science who would later become his wife. After a trip and accompanying video series, “Lost in North America,” he did his stint on the national competition circuit, collecting his fair share of podium finishes. But then, spurred on by his yearning for exploration and adventure, came his biggest adventure to date.

Also read: What You Need to Know About the Olympic Climbing Wall

Also read: The Complete Guide to Olympic and World Cup Speed Climbing

Also read: Team USA’s Secret Weapon: Head Coach Josh Larson

Also read: The Olympics Are in Tokyo, Is Team Japan Poised to Beat Everyone?

Also read: How Team ABC Built Two Olympic Climbers Brooke Raboutou and Colin Duffy

Also read: Olympic Wildcard Colin Duffy May Be the Youngest Climbing Competitor—and the Spoiler

Throughout a year-long documentary series, “A World Less Traveled,” Josh and Charlotte established first ascents of routes and boulders across six continents. From bolting routes at 14,000 feet in Peru to climbing Tasmanian coastal spires, they scoured the globe for untouched rock, including in previously undeveloped areas in Puerto Rico, Brazil, South Africa, Greece, Serbia, and Japan. One of their most notable objectives culminated in a 600-meter, 17-pitch 5.13a big-wall first ascent in Tsaranoro, Madagascar, called Soava Dia—they sent all the pitches in a one-day push, except for pitch 13.

Of course, their round-the-world trip had its exciting-cum-dangerous moments, too.

One day, a few hundred miles from the nearest town of San Ignacio, buried deep within the lush, green jungles of Belize, Josh rappelled a granite cliff high above a river, unaware of the peril awaiting him below.

Honey bees had begun stinging, scratching, and clawing around his eyes, ears, mouth and nose.

“All of a sudden, I couldn’t see or hear anything,” he says—thousands of black-and-yellow Africanized killer honey bees had begun stinging, scratching, and clawing around his eyes, ears, mouth, and nose. The bees were trying to suffocate him. “This is where I am going to die,” he thought to himself.

Knots in the rope blocked his rappel device, so Josh hand-over-handed 40 feet back up the rope to the top of the cliff where he was forced to jump—without spotting his landing. He miraculously plunged into deep water, unscathed, but the swarm was undeterred. His body staving off anaphylactic shock, Josh plummeted through 20-foot waterfalls, the half-inch death machines following him downriver. “Each time I came up for a gulp of air, they were there waiting for me, ready to rapid fire my skull and face. I could even feel them underwater in my hair leaving their stingers in my dome.” After about a mile, the bees dispersed.

At another stop on the World Less Traveled tour, where he and Charlotte were climbing off the grid in Madagascar, he took a four-hour detour from the climbing area through the wilderness to find a restaurant with wifi for a previously scheduled call with Marc Norman, the president of USA Climbing.

Norman was looking to hire a head coach for Team USA ahead of the 2020 Olympics. He offered Josh the job.

“I had to say yes,” says Josh. “I felt like if I didn’t take the job, I would have been passing up the chance of a lifetime.”

Cutting his global climbing circuit short by four months, Josh made the leap to Salt Lake City to help run the novel USAC High Performance program, to be based in a hypothetical training center under the theory that America’s top competitors would all thrive under a single roof, leading to success at international competitions, and, hopefully, medals at the Olympics.

Back in Salt Lake City on the morning of the mock comp—a simulation of the Olympics combined format—Bouldering National Champion Natalia Grossman confidently approaches the center of the local Millcreek Momentum’s overhanging headwall. The gym is hushed, with all eyes fixed on her as she glides seamlessly up the wall.

John Muse, High Performance Director, observes the round with members of the International Olympic Committee. Earlier in the week he told me that his detail-oriented mentality and Josh’s free-flowing approach has created some challenges.

“There is quite a bit of difference between us. He’s challenged me to think outside my box, to not just live in this square box that I like to live in where everything’s got to fit in this little parcel,” says Muse about his need to have logistics and scheduling sorted out months in advance. “But Josh’s soft touch, his flexibility and willingness to grow and evolve with this new program, has been invaluable.”

After Natalia comes close to topping the route, Kyra Condie, an Olympic qualifier, takes her turn and doesn’t have the try she is looking for. Tears well up in Kyra’s eyes.

“Can I skip speed this afternoon?” she asks Josh. “My skin is wrecked.”

Josh reduces his voice close to a whisper as he attempts to assuage Kyra’s doubts—something the athletes will have to deal with moving from one discipline to the next in a single day of competition. Instead of focusing on rebuilding her skin, he works on bolstering her mindset.

“I never want to say too much, where it becomes just noise, and I don’t want to say something where I’m not helping. I need to say the right amount at the right time,” explains Josh, referring to a lesson he learned from one of his Slovenian coaching mentors, Roman Krajnik. “Some coaches say too much, and some say too little. Roman says just enough.”

Kyra, who kept climbing for the rest of the day, let me know that Josh’s ability to listen and make comments with intuitive tact also applies to how he coaches movement. “I’ll be working on a problem for hours, and Josh will come over, help point out a few things, and then I’ll do the climb next try.”

After a few rounds of speed, the athletes prepared for their final event that night: bouldering.

The setting sun casts a pink glow on the Wasatch Mountains to the east as we make our way back to the training center for the bouldering round. Josh pushes the gas pedal down with his plastic boot, cranks the e-brake, and drifts around a corner strewn with the flapping tarps and tents of a homeless encampment.

Once inside the training center, we sit down on some dusty volumes tucked away behind the climbing walls while his black-spotted dog, Lulu, takes another lap around the pads out front.

“When we started climbing, did you ever imagine we’d have all this? The sky’s the limit now,” says Josh, pushing his catcher’s-mitt-sized hand against his stubbled chin, crinkling the skin up and down his face as he considers the future.

“The athletes are here because of what they have done, not because of what I have done,” he says. “But there are pieces missing and if they want to go up against the elite in the world, they have to put these pieces together.”

One of those pieces, the mental game, is at the forefront of Josh’s mind.

“Everybody has the plan for feeling good, but nobody has the plan for when things start going wrong,” he says. “It’s in these moments of failure that you’ve got to be able to focus on just controlling what’s right in front of you, not what’s way out here,” he says, stretching both of his hands far away from his head. “And if you don’t have the mental fortitude when things start to go south, you’re not ready. And you don’t know what to do. That’s when even the best athlete can tumble. That’s what I want to prepare them for.”

Ultimately though, Josh also has dreams of his own. Later that night while sitting on the couch, we devour a pint of Ben & Jerry’s Phish Food while playing GoldenEye on his new Nintendo 64. As usual, we start scheming about the future. Josh lays out his retirement plan: to buy land in the Andes of Peru, run a farm and a climbers’ hostel equipped with a beer and pizza bar, and spend the rest of his days chasing down king lines at 14,000 feet.

“That’s the plan at least,” he says. With his luck, he might just end up on the moon.