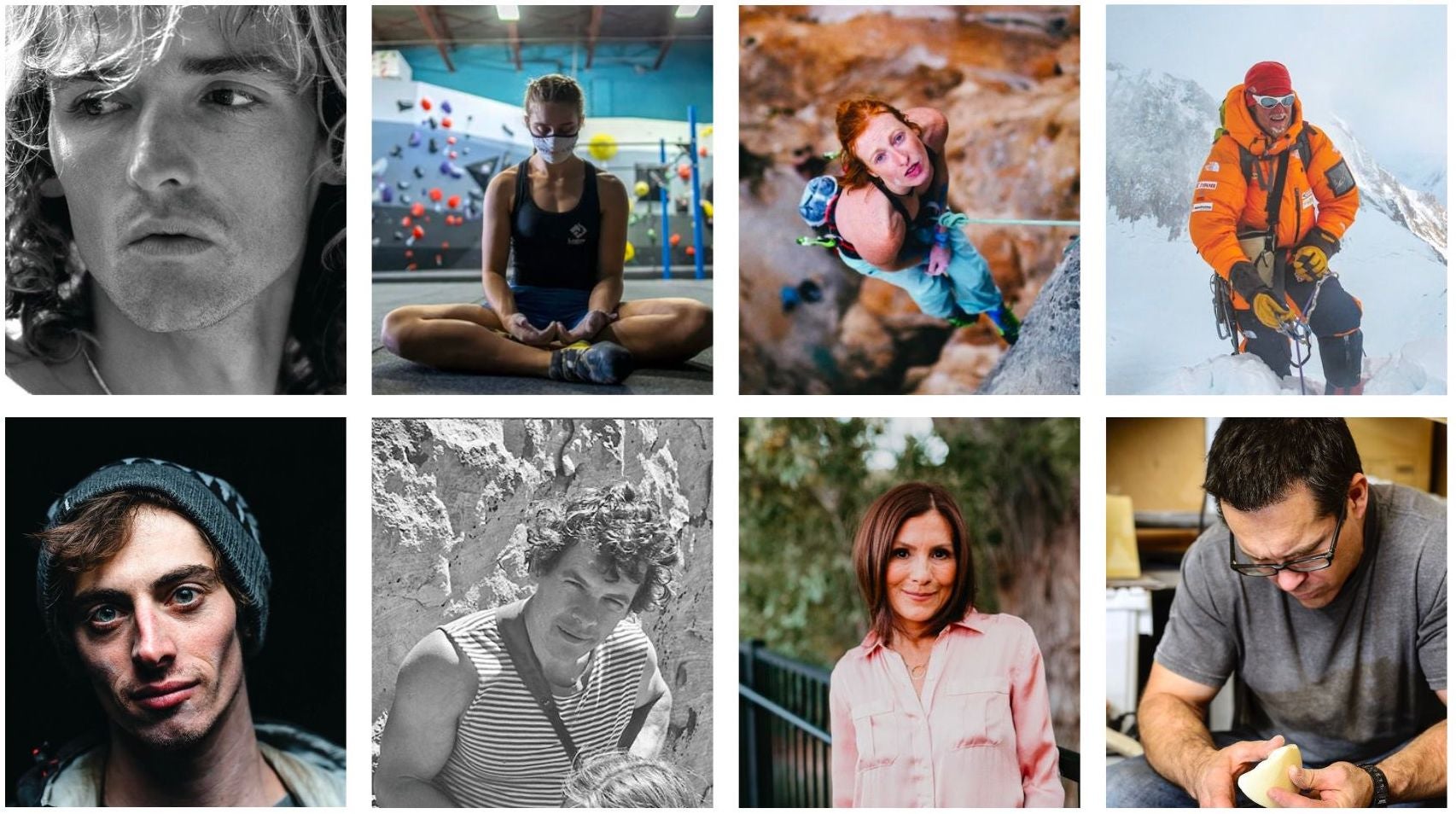

Our Best Articles About Mental Health and Climbing

Depression, addiction, bipolar disorder, PTSD, eating disorders, severe grief, dangerous loneliness. Climbers, as humans, can experience any and all of these things.

To honor Mental Health Awareness Month we’ve gathered some of our best stories on these subjects, stories about icons whose fame pushed them toward isolation, depression, and alcoholism; stories about young crushers whose drive to get strong saw them eating so little that it negatively impacted not just their climbing but their health; stories about guilt and grief and the spiral of self-hatred and abuse that these emotions can lead to; stories about the drug- and alcohol-abuse that has all-to-often ransacked the lives of beloved members our of community; and more.

These stories are arranged alphabetically by author.

—The Editors

The Triumph and Tragedy of Patrick Edlinger

By Ed Douglas

He was the first true icon of sport climbing, famous across 1980s France for his daring exploits and bohemian lifestyle. In 2012, fighting depression and the bottle, he died in a tragic accident at just 52. What happened?

“There was something wolfish about Patrick Edlinger, who spent his last decade here. A photograph of him by Guy Martin-Ravel, one of the few images from his zenith that the older Edlinger—puffy-eyed from cigarettes and alcohol—allowed on the walls of his house, captures the notion perfectly. His face is narrow and long, framed by a shock of blond hair, his lips slightly pursed. The whole effect teeters dangerously toward the parody of a 1980s rock star, except for the eyes. Edlinger’s gaze is fixed in the middle distance: intense, black—and hungry.”

*

A Lost Boulderer Battles Back from Addiction

By Nate Draughan

An honest account by a top climber who hit rock bottom

“I woke up as cops were pulling me out of the car. On me I had half a gram of heroin, 10 Xanax, a couple of morphines and three needles—enough at least for a year in prison. Not long after the cops started rifling through my backpack, Zach, my halfway house manager, showed up. Zach was fit, into fishing, and he had just gotten off his late-night stocking job. I think I had called him earlier in the night, to let him know I was going to be late, but I don’t remember. Somehow, he found out I was at the Denny’s.”

*

Stephanie Forté, One of the First Climbers To Speak Up About Eating Disorders, Looks Back

by Stephanie Forté

This essay on anorexia and bulimia was written in 1996 by Stephanie Forté, then age 29, and published in Climbing’s perspective section that year. Forté was perhaps the first American woman climber to write about the issue, which took courage, but she notes that she’d write about it differently now: “If I wrote that essay today, the ending would not be tied up in a bow, ” she writes us in an email. “The impact of an eating disorder on my life has been far-reaching and multi-layered.”

“In our small subculture of climbing we have published articles hinting at the fact that eating disorders may be a problem in our sport. They are. Having been anorexic and bulimic for 17 years, I feel I can call myself an expert on the subject. More than half of my life and most of my energy have been devoted to this disease. We are so entwined in one another that sometimes I don’t know where I end and it begins. It has been my security blanket, a source of power, and my worst enemy, and just might take me to an early grave.”

*

Stonemaster John Long Comes Clean on Alcoholism

By John Long

Climbing has long celebrated hard drinking and drugs. Many climbers become lifelong alcoholics and addicts and their families, friends and climbing partners bear the high price. One of climbing’s most iconic figures fell into the pit, but pulled himself out and now has an important lesson every climber should read.

“My journey to escape hell is nothing special or unique. There’s an understanding in recovery rooms (especially AA, my path of choice) that we’re basically all telling the same story, but those of us with a genius for denial, dishonesty and self-deception have to hear it over and over to hear it at all. Then we need to keep hearing it to stay the course. ‘Eternal vigilance.’ ”

*

His Father Died At His Feet. 50 Years Later The Accident Still Haunts Him.

By Steve Markusen

50 years ago, Steve Markusen’s father died when a rappel anchor failed—fatally falling 50 feet in front of his two boys.

“This is a story about that day and the aftermath: denial, loss, depression; alcohol and drug abuse. Looking back, I see a pattern of self-destruction, perhaps attempts to sabotage my life. Writing about it all these years later is about redemption and healing.”

*

Coming Up For Air: When Climbing Isn’t The Only Battle

By Delaney Miller and Mimi Nissan

Two leading comp climbers of their generation reflect on the way disordered eating informed their climbing.

“Despite being rail thin, I couldn’t make it through a single day without counting calories, thinking about how fat I was and all things I could be if I could just be anyone else. Despite all of the training, the coaches, nutritionists, therapists and doctors, I still hadn’t been able to stare into the crystal ball and see my escape, because that would be admitting that I needed to.”

*

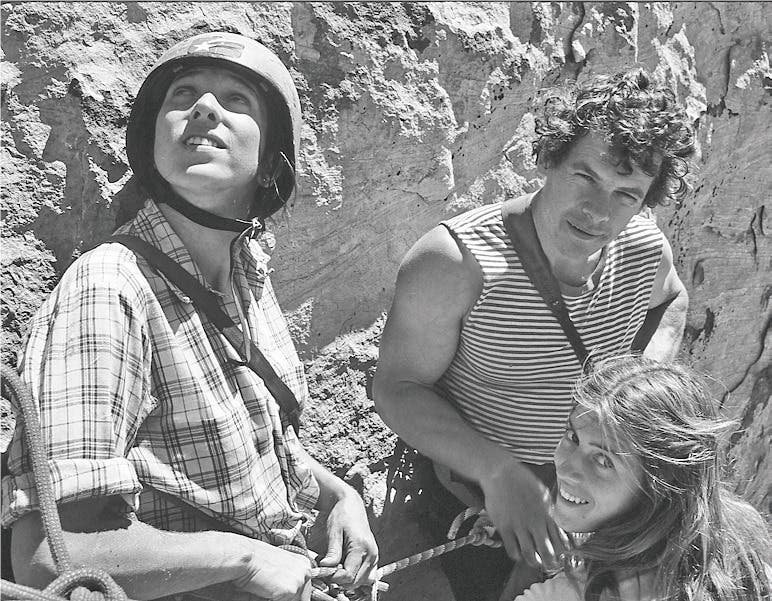

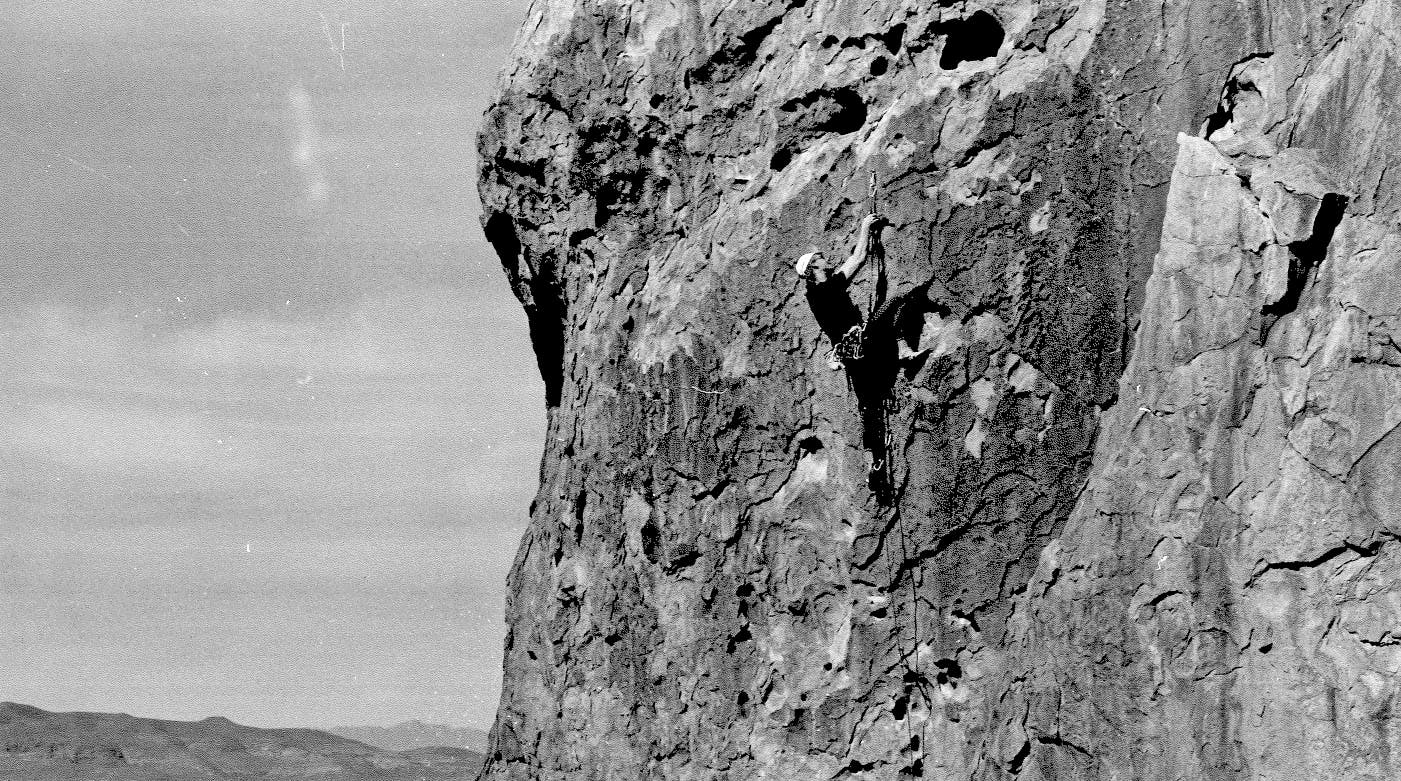

The Daring Life and Untimely Death of a Climbing Pioneer

By Alison Osius

Earl Wiggins was a leading free climber and soloist in the 1970s and 1980s. (He did the FA of Supercrack / Luxury Liner in Indian Creek… placing hexes.) But in the early 2000s, he took his own life.

“Wiggins died in December 15 years ago, by his own hand in Lake Oswego, Oregon. Much is unknown about the highs and lows he experienced, the losses and disappointments he endured, and the nature of a kind, questing and troubled person who found his true self—in a way that must have seemed a miracle—in climbing.

Green was, he says, ‘astounded’ upon his friend’s death.

‘I just couldn’t believe it. But you never know what’s going on in people’s lives. Jimmie and I talked about it for years: Why didn’t he call us? Why didn’t he call his friends? … We were all willing to help, to do whatever.

We still don’t know why he did it.’ “

*

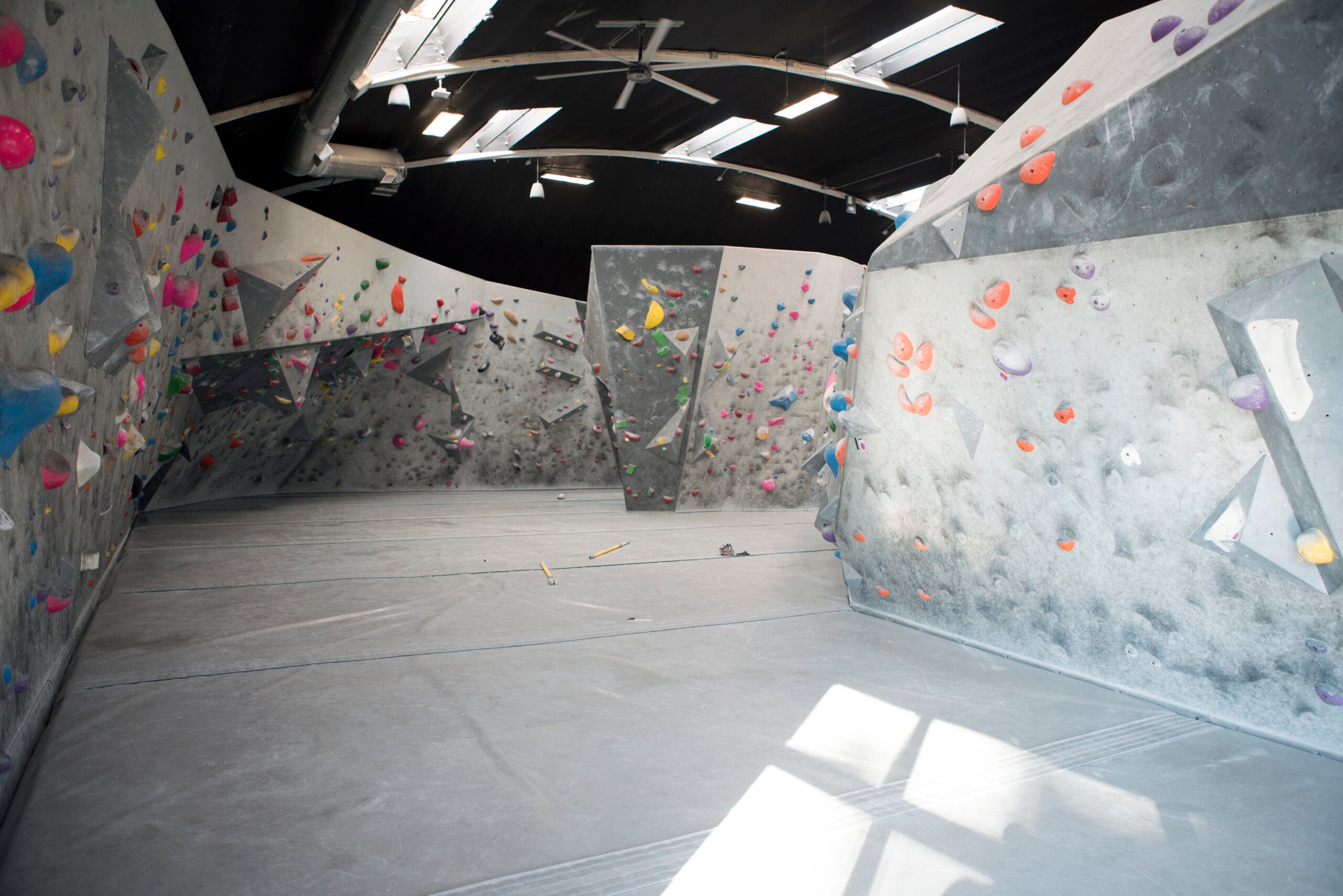

Should You INTENTIONALLY Go to the Gym When it’s Crowded?

By Steven Potter

This column is about loneliness in America and how sometimes devoted climbers misunderstand, or forget, the things that climbing can do for us.

Last year one of my oldest, dearest friends—let’s call him Gary—called me up and informed me, over the course of an increasingly upsetting half an hour, that he was “dangerously lonely.”

“What do you mean by dangerously?” I said, Googling flights.

“I don’t know,” he said. “I’m fine. It’s just…”

So I told my boss I was sick, got on a plane, and flew to California. And while I was in the air, I tried to imagine how Gary—who I’d first bonded with under a spray wall in college—could end up like this. He was a fifth-year PhD student in a city bursting with active and educated young people. He was a climber who lived within biking distance of the gym. And he worked in a department where he and his coworkers could presumably bond over esoteric academic-y things. Surely he knew someone, right?

*

Why is Cory Richards Retiring From Climbing?

By Steven Potter

This profile and interview of photographer and climber Cory Richards, the only American to-date to summit a 8,000-meter peak in winter, discusses about Richards’ battles with PTSD, bi-polar disorder, and addiction—and why climbing is no longer a healthy part of his life.

“On the one hand, what he experienced was a mental-health emergency: a nightmarish reignition of old traumas coupled with undertreated bipolar disorder. On the other, Dhaulagiri saw Richards finally acknowledge that his almost Faustian relationship with climbing—a sport that has provided him with wealth and fame and external validation—was no longer sustainable … and may never have been.”

*

If You Climb Long Enough, You Will Lose People

by Matt Samet

As climbers, we can—perhaps all too easily—make sense of a comrade falling to their death. It’s a grim reality, but we understand that these things happen. But sometimes we lose people in other ways too.

I found out about Randall’s death the way we learn about most of these things these days: the web. It was 2010, and his brother had posted a Facebook page soliciting memories of Randall from friends. Someone either tagged me or sent me the link, and that’s how I found out Randall Jett had died.

I’d known Randall since my high-school years. He worked part-time at the Wilderness Center, an outdoor shop in Albuquerque, New Mexico, that was about halfway between my school, Highland High, and my home. On weeks when I saved up my lunch money, I’d stop in to buy chalk or the latest climbing magazine. It was the late 1980s, and one Rock & Ice cover featured a lizard climbing an overhang—like a terrarium rock—while wearing a miniature chalkbag. No shit: a lizard with a tiny chalkbag!

*

Organ Failure and Diet Pills: How a “Shrink-to-Send” Mentality Upended Her Life

By Gabrielle Tourtelloutte

In her attempt to become a top competitor, Tourtelloutte embraced the “shrink-to-send” mentality… there were long term consequences.

“ ‘Gabbs, you look kind of yellow.’

I’d rolled my eyes, ‘No I don’t.’

My dad chimed in from the other room, agreeing with my then boyfriend, Mike, ‘No, he’s right, you are yellow.’

But where? I’d asked myself. Later that evening I checked in the mirror and there it was, in my eyes and skin. I was surprised I’d missed it. Soon after though, I received a call from my doctor. As per my last round of blood work, I was in liver failure, which explained the yellowing of my skin and eyes. I hung up and didn’t think much of it. A few weeks later, I competed in my last Youth Sport and Speed Divisionals with a broken right ring finger and a partial tear to the A4 pulley tendon. Three days after that, I was hospitalized for anorexia.”

*

His Holds Changed the Climbing Industry. Then Came Drugs, Fake Credit Cards, and Worse.

By Caroline Treadway

Ever climbed on a Kilter Board? Even if you haven’t, you’ve almost definitely climbed on Ian Powell’s holds. He was one of the most influential shapers in the industry; then he went to prison. 11 years free, he’s since changed the industry again as one of Kilter’s founders.

“Ian Powell hit bottom three years ago on Thanksgiving in a dumpster near Denver. Huddled under a layer of trash, he was freezing, dope-sick and hadn’t eaten for days. He had no friends who weren’t junkies or criminals. He couldn’t remember the last time he’d climbed, but it had been two or three years. Most important, he wasn’t producing art. He needed to make art. Sifting through the dumpster, he found some paper and pens and drew until his hands were numb.”

*