Alannah Yip Didn’t Have a Picture-Perfect Career Ending. And That’s OK.

Alannah Yip is one of Canada’s most decorated comp climbers. She was the sole female to represent Canada at the Tokyo Olympics, and, last October, won the country’s first-ever Sport Climbing medal in a Pan-American Games (bronze, in Boulder & Lead). She’s also ticked 5.14a (Squamish’s Pulse, first female ascent) and V12 (the stunning Room Service) to round out her climbing resume.

As a fellow Canadian, I eagerly followed Yip’s performance in the lead up to the Paris Games, well aware that she was one of the few Canadians strong enough to qualify—and that it would be her final competition whether she did so or not.

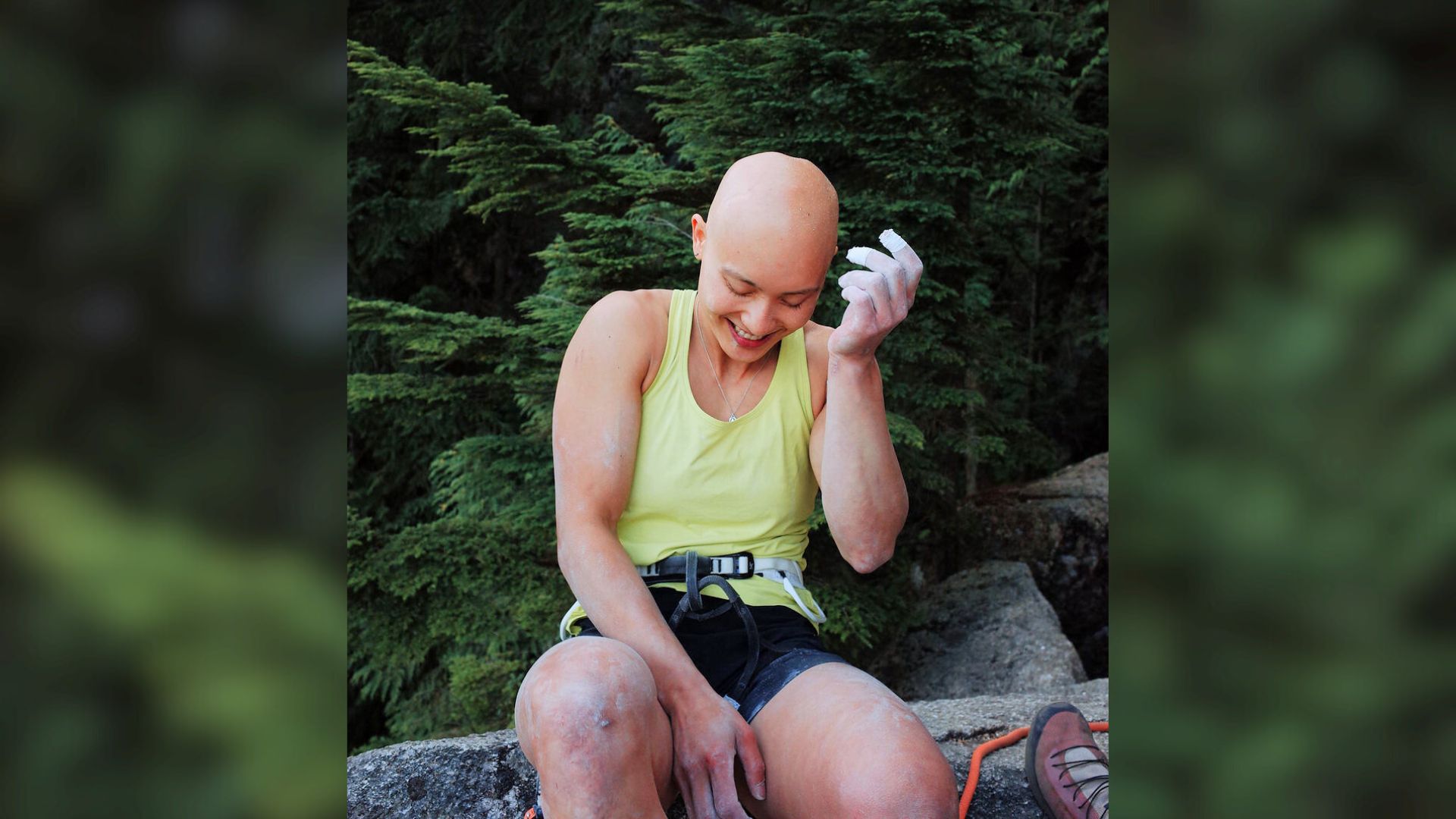

Well, spoiler alert, Yip didn’t make the cut. A lot went down in her life between Tokyo and Paris, not the least of which included: finding funding, losing funding, changing coaches (she’s “not great” with change), falling out of love with competitions, falling back in love with competitions, learning to channel music into climbing performance, and learning to live and climb and compete and feel beautiful with the auto-immune disease Alopecia, which causes significant hair loss. Last week I sat down in a cafe with Yip at the Arc’teryx Climbing Academy, in Squamish, B.C. We talked about her hair loss, her illustrious comp career, mental training, her transition to full-time rock climbing, and more. Then we got in a few pitches at Cheakamus Canyon, where I begged her to tell me her outdoor-projecting secrets. (I included a few of them below.) Our conversation has been lightly edited for length.

The Interview

Climbing: I recently listened to your conversation with the Nugget Podcast, and one topic that stuck out to me was your hinting at the Canadian comp scene’s clear lack of resources. Can you tell me what it’s like to be an Olympic hopeful in Canada compared to the U.S.?

Yip: The athletes receive very little funding. The corporate sponsorship Canadian climbers do receive rarely ends up in their pockets—it usually pays for salaries at Climbing Escalade Canada (CEC) instead. I’ve personally paid my own way for nearly every competition I’ve attended, except for the Tokyo Olympics, the Pan-Am Games, and a few other exceptions. As a result, since I was 14, I’ve always had a part-time job alongside highschool or university to pay for my competitions. And I’ve had to be very frugal to pay for the comps. But it’s what I loved to do.

Climbing: Right. Some people save their money for a relaxing Caribbean vacation—

Yip: And I take myself on a really stressful vacation!

Climbing: So how does that lack of funding differ from the U.S. climbing team?

Yip: The U.S. has different tiers; the top tier, since 2019, has been fully paid for: flights, accommodations, meals, transportation within the country, training, etc. This type of financial support is common in other countries, including Switzerland, Austria, Japan, and Germany.

Climbing: What was the lead up to the Paris Olympics like for you?

Yip: The Olympic Qualifier Series (OQS) events (Shanghai and Budapest) were put on by the IOC and very cool. They are two massive multi-sport events—kind of like mini-Olympics—with paid-for flights and accommodation, buses to the venue, accreditation, and everything. The events included Sport Climbing, BMX, Skateboarding, and Breakdancing.

Climbing: Nice. So, like, all the cool sports.

Yip: Maybe just missing three-by-three basketball.

And there were thousands of spectators, merch for sale, and interactive booths where you could try skateboarding and climbing. Very cool. But, personally, going through Alopecia this year, it’s been quite a roller coaster and, before both events, I had a couple things that really rocked my confidence—especially before Shanghai. It became really hard for me to step out onto the mats and into the spotlight and actually climb the way I wanted to.

For example, there was a pool at the hotel in Shanghai, so the day before the comp I was excited to go for a swim. I went to the front desk of the pool area, and he pointed me toward the women’s changing room, and I walked in and there’s two old Chinese women who said something to me in Chinese. I didn’t respond, since I don’t speak Chinese, and then they started shouting at me: No man! No man! And started hitting me. I was shocked. I ran out of there so upset.

I was already struggling, trying to be confident in myself while out on the mats. It’s a vulnerable place: being the center of attention out there. And I didn’t realize how hard competitions would feel with Alopecia, compared to normal life, where I’ve kind of gotten used to being bald. So rather than feeling like I wanted to climb and perform in Shanghai, I just wanted to curl up and hide.

That was a hard time for me, but it was also cool to see the progression between then and Budapest one month later. I’d been working with John Coleman, the sports psychologist that Arc’teryx has on retainer for its athletes, which has been amazing, and in Budapest I was able to show up in a way I was proud of, and climb like myself and have fun. My competition career couldn’t have ended on a better note for me.

Climbing: I read in an Instagram post that in Budapest, where you placed 15th, you were able to tap into a flow state that had eluded you for several years. Those several years would have predated your experiences with Alopecia—so what else was blocking you from finding that flow?

Yip: It was a crazy year leading up to the Tokyo Olympics. It was hard for me when the event was postponed, but I still needed to continue training for the biggest event of my life—and this time in total isolation, not being able to train in Europe with other people like I normally would. Instead, I was just by myself, with no gauge of where I was in relation to my competitors—and with no funds to hire a comp-specific setter like other countries could do. Having the Olympics be my first competition in 16 months was also hard. I thought I would be unbothered by the extended delay; that it would be just another comp; that I’ve been competing for so long that I would know what to do when I showed up. Turns out, that pause in competitions really affected me.

Climbing: Why do you think that was?

Yip: There were a lot of factors. We had a big change in coaching, and the coach I’d worked with since I was a little kid was no longer there anymore. My new coach was great, but there was a lot to catch up on. I’m not great with change.

After that, a few poor competition results also shook my confidence, and it took me a while to let go of wanting certain results at competitions. It wasn’t until my final competition, at the OQS in Budapest—where I knew that I was no longer in the running for an Olympic spot—that I was finally able to shake the weight of expectations I’d placed on myself. It had been a while since I’d climbed so freely.

Climbing: I’m curious how that experience at Budapest compares to your earlier competition experiences. Tell me why you fell in love with competing in the first place.

Yip: I really loved solving puzzles. Every problem was new, all the time. And especially in the beginning, nobody expected anything of me. Nobody knew me. It didn’t matter if I had one bad comp; I believed I belonged there. And that’s part of what I lost in those intervening years: the confidence that I deserved to be there.

Climbing: It’s interesting that it was only once all the stakes were lowered, and that there was no chance you could qualify for the Paris Olympics, that you could finally perform in the way you wanted to—for the love of it. But I also think it’s a symptom of being a hyper-motivated professional climber: results do matter, and you may not have gotten the chance to compete in Budapest with a laissez-faire attitude. There’s an elusive mindset to be had, somehow, of climbing without a mental burden, but still performing like you have everything to lose. Given all that, I’m curious why you stuck with full-time competing for so long, even while you were finding success on the rock too. What was keeping you inside?

Yip: Post-Tokyo, and all the uncertainty leading up to it, I knew I wanted an Olympic redo. I wanted to go to Paris. I felt like I owed myself another chance at the Olympics. And I knew that if I didn’t at least try to qualify, it would have been because I was scared of failing. I didn’t want to give myself that out; I didn’t want to give up on myself. And my new coach believed in me in a way I had never experienced before, and meanwhile also started coaching Jenya Kazbekova of the Ukraine, who competed in Paris, and who became a really great climbing partner of mine. We climb at a similar level but have very different strengths. I think she’s one of the best slab climbers in the world.

Climbing: Failure in competitions is so obvious: there is one winner and many losers. Or those who stand on a podium and those who don’t. How do you think about outdoor climbing, where you could try one boulder for a hundred days and not be considered a failure?

Yip: “Failure” has always felt like a very personal thing for me. I’ve never been under the illusion that I’m the best in the world, so failing was never related to winning or not. For me, failing meant that I was not climbing my best, or that there was an external factor like fear of failure holding me back. So, with outdoor climbing, I suppose you could fall into those same traps of success and failure, although I try to give myself grace on days on the project with negative progress.

Climbing: What sort of mental training, if any, do you do?

Yip: There are no mental exercises that I do, but I do a lot of journaling and free writing that has been helpful for working through feelings of doubt while projecting and competing. My sports psychologist and I have also done a lot of work about my mindset, and how to tap into a healthy mindset while competing. We call them “doorways” into specific mindsets, and have explored how one type of mindset might be more useful than another in certain scenarios.

Climbing: Can you give me an example of a doorway?

Yip: My performance mindset is usually a pretty happy, relaxed state where I am enjoying myself and the climbing. I can tap into this mindset while coming from one of two places: either I am stressed and I need to calm down into this mindset, or I am too relaxed and need to hype myself up somehow to perform. The best “doorways” for me come from music. I bring an iPod Shuffle with me to all competitions that has 10 songs on it. A couple chill songs, a couple medium-hype songs, and a couple really hype songs. Sometimes dancing, or smiling, is a doorway into a hyper-motivated mindset. Other times it’s playing cards, or reading a favorite book.

Climbing: Do you think there’s much crossover between high level competition climbing and high level outdoor climbing?

Yip: There definitely can be. Both disciplines require a lot of strength to succeed at the highest levels. In outdoor climbing you can be a lot more specific with the styles you climb on. Competitions require you to have a bit more fluency between styles. But for sure there is crossover: just recently Janja climbed V15, and Brooke climbed Box Therapy (V15 or V16).

Climbing: On a totally different topic, are you tired of people asking you about your Alopecia?

Yip: No, not at all. I feel like everytime I share about it I hear from someone who has experienced it themself, or their kid has and my post helped them feel more comfortable with themselves. And that feedback makes me want to share about it even more.

In fact, almost no one has treated me any differently because of Alopecia. The main crux has just been dealing with my own feelings towards it. But I have been misgendered a few times: by those women in China, and in the U.S. where some people just have to add “Sir” at the end of their sentences.

Climbing: Do you think your experience with hair loss affected your climbing at all?

Yip: It did when I was competing in Shanghai, and at the Salt Lake World Cup right before that. Salt Lake was the first time I’d done a big competition without hair, and I felt so exposed. Shanghai was the same feeling. I was more worried about my lack of hair than the actual climbing. I just felt so different out there.

But I worked through it with my sports psychologist who reintroduced me to a very simple concept I’d forgotten about: you can choose what you find beautiful. I could just choose. So simple, but life changing for me. I’ve felt a lot better since then.

Climbing: What are you most looking forward to this year?

Yip: I’m excited for my schedule to not be filled with competitions anymore, and for future overseas trips. But I’m most excited about signing a contract with Arc’teryx last week, as an engineer supporting the testing team.

Alannah’s top 4 tips for sport projecting

-

- On figuring out impossible moves: Stick clip up and take so you can get weight off your arms, and feel all the available holds and test all possible body positions. Consider working down from key holds or rests, rather than solely working up.

- Warm up: It’s not just about injury prevention. I can’t climb my hardest without a proper, full-body warm up including shoulders, fingers, and hips. I do 10-15 minutes of ground warm up before doing my first pitch. On that first warm-up pitch, the goal is to warm up—not send! I’ve taken on 5.9 before if I get confused. Do not get pumped on the warm up. If I’m doing a 5.14a project, for example, I would warm up on an 5.11+ and then a 5.12+/13-, and then do finger-specific warm up on a hangboard I’ve brought.

- Be efficient when resting: It’s easy to get impatient at rests, and leave them before you’ve milked them for all they’re worth. I like to decide how long I need to be at that rest beforehand, and then have my belayer set a timer to hold me accountable.

- On big projects, set smaller linking goals: We all need smaller victories on the way to clipping the chains. Before giving redpoint attempts, I will make a goal of linking from the ground to the end of the crux. Then I’ll try to link from the beginning of the crux to the chains. These overlapping links help mentally, too. I will make more mini-goals the longer term my project is.