A Short History of the Climbing Gym

In 1968, John Syrett, an 18-year-old novice, stepped up onto the slick rocks cemented into a brick corridor at the University of Leeds, England, and found magic. Talented and fluid, with dark eyes and curly black hair, he was soon a fixture on the scene and outclimbing everyone. Yet many people in the era doubted that skills on an artificial wall would apply to real rock.

Throughout rock climbing over the last 50 years, you see the same story: Someone climbs or trains in a gym and busts out. The U.K. climber Ben Moon came out of a cellar gym to produce Hubble in 1990, and Chris Sharma went into a gym at age 12 and at 15, in 1997, claimed the first ascent of the Virgin River Gorge’s Necessary Evil (5.14c), the hardest climb in this country. Two years later, Syrett onsight-led what was likely the second ascent of the Wall of Horrors, a runout 5.10 and the country’s hardest route.

Before Syrett’s day, most climbers did not train per se, nor understand the benefits. Other kinds of walls had existed here and there—with adjustable wooden ones in France as early as the 1950s—but the University of Leeds wall, put up by a phys-ed instructor, Don Robinson, to help climbers maintain over winter and prevent injury, is widely credited as the first real climbing wall for training, an icon.

Fifty years later, gym climbing is projected to be a billion-dollar activity, with over 600 commercial gyms frequented annually by five million climbers, more than the number of sport, trad, ice and alpine climbers, and boulderers combined, and that is just in the United States. Overseas, Germany—a country smaller than the state of Texas—alone has more than 280 climbing gyms. Japan, about the same size as California, has over 500.

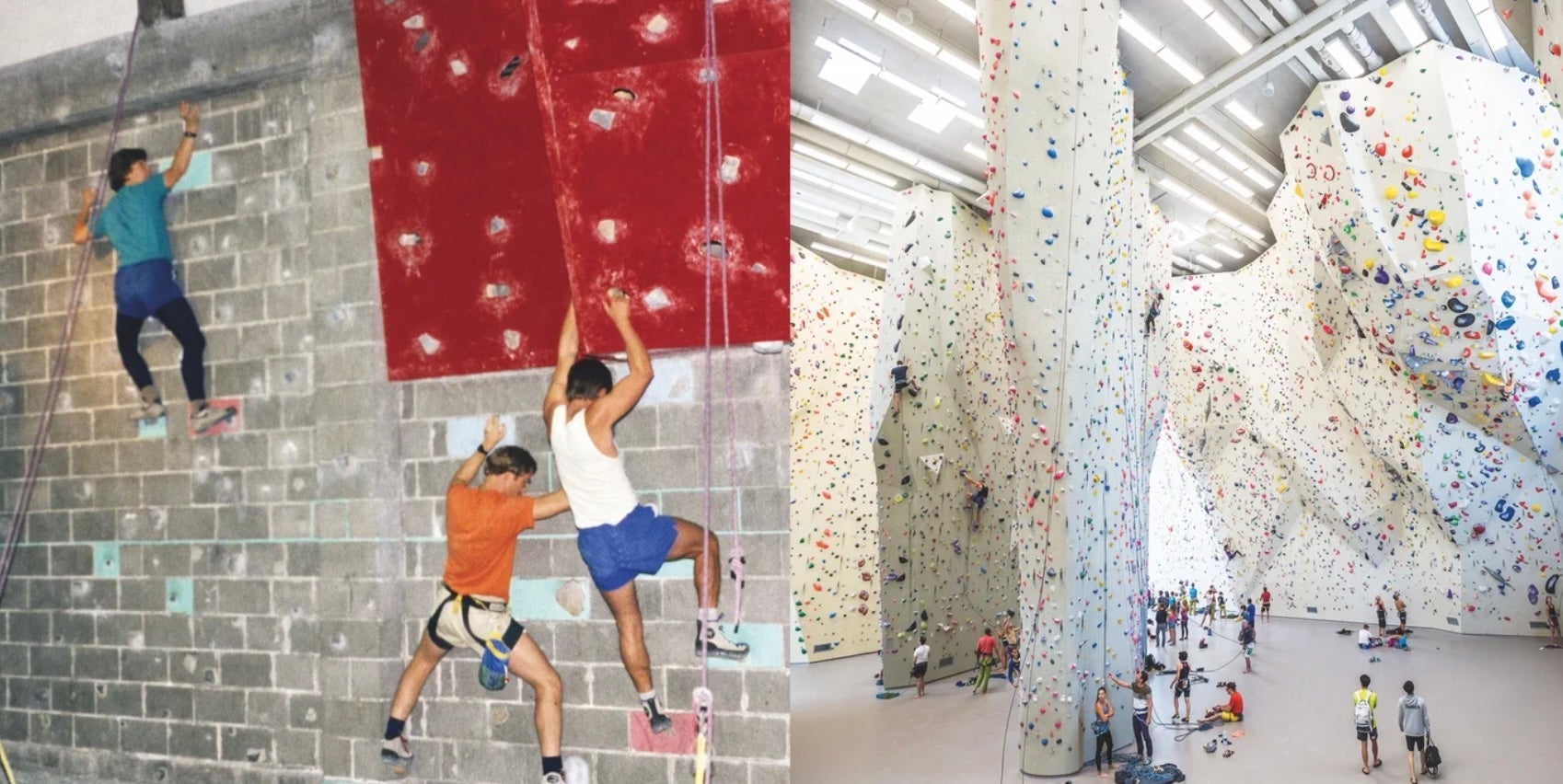

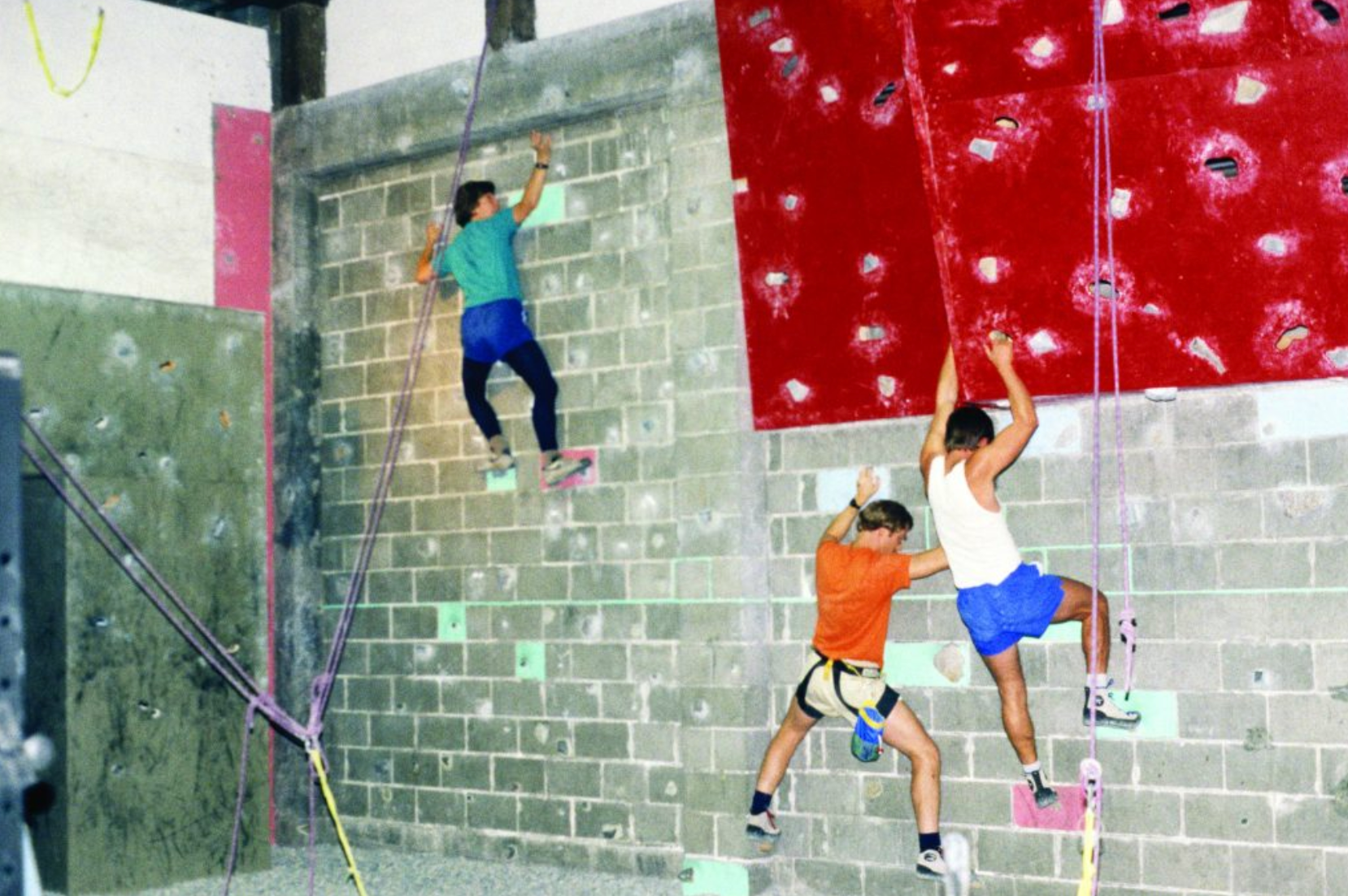

Gone are the days of real rocks epoxied to cinder-block walls. Today’s gyms are custom-built, often with steel framing and sculpted modular panels that are as much art as exercise equipment. Climbing gyms can have thousands of members and be multi-million-dollar investments offering yoga and pilates classes, the services of professional trainers, and amenities like weight rooms, coffee bars and cold brews. Today’s climbers can make a living setting routes for gyms or competitions, and competition climbing on an indoor wall is an Olympic sport. Where indoor climbing was once simply a way to train during the off season, it is now a sport unto itself—many gym climbers have no interest in ever climbing outdoors. How did we get here?

***

As early as 1975, the University of Washington set up a 40-foot outdoor wall, and though use depended on weather, the facility developed a fast following. Many climbers also “buildered” on college walls or screwed strips of wood to garage walls and crimped on those. In the 1980s, L.A. climbers glued holds onto the concrete of highway underpasses, creating a whole scene.

In 1983 a lightbulb went off with French climber François Savigny. Instead of making holds from rock or wood, he’d mold them from plastic and put a bolt hole in the middle so the holds could be easily moved around. It was a genius concept, one that would birth indoor climbing as we now know it. With less than $50,000 in seed money, he founded the company Entre-Prises. Savigny made the first molded holds in 1985 and a year later developed the first climbing panels. In Europe, Savigny’s fledgling company put climbing walls in municipal buildings and schools, fabricated boulders for parks, and sold holds to climbers, but the commercial gym remained futuristic.

In 1986, Chris Grover, a Metolius employee and early advocate of sport climbing, and Alan Watts, the major developer of sport climbing at Smith Rock, attended a trade show in Europe and saw Savigny’s plastic (resin) holds for the first time. They returned to Bend, Oregon, with two samples.

Upon their return, as Watts reminisces in an email, “[Grover] showed the holds to Doug Phillips [Metolius founder], and they started playing around with molds and resin,” beginning a process of experimentation. In the summer of 1987 Grover began to design hangboards and large sculpted tiles that you could puzzle together and screw onto plywood walls. Watts began working at the company as well.

Shortly afterward, a company named Vertical Concepts, also of Bend, began marketing climbing holds. Kent Olmstead had started with wooden holds, and in 1987 began experimenting with resin compounds, creating Rok Buildering Bloks.

In early 1988, Metolius took its hangboards, tiles and holds to a trade show in Las Vegas, after which Savigny approached them about teaming up to import his holds. That autumn Watts and Grover left Metolius to found Entre-Prises USA; Phillips invested in it, as did they, and EP USA was up and running.

“To be honest,” says Watts, “I never saw the enormous potential in climbing holds and gyms. The whole climbing-gym industry in the U.S. was just a bunch of dirtbag climbers trying to avoid getting a real job. It was not a good decision for me to leave Entre Prises in 1997. I would be driving a much nicer car today if I persevered. I figured that the climbing-gym industry would never amount to much.”

***

In January of 1987, two Washington climbers, Rich Johnston and Dan Cauthorn, had been sitting in a tent at 20,000 feet on Aconcagua when Johnston, a mountaineer, asked, “What do you rock climbers do during the winter to stay in shape?”

“I don’t know,” Cauthorn had answered. “We just do pullups in the basement and drink beer.”

“Isn’t there a rock-climbing gym?” Johnston asked. Cauthorn looked bemused, but Johnston couldn’t shake the idea; other sports had means of year-round practice.

Back home, he collected information, buying subscription lists of local climbers from Rock and Ice and Climbing magazines; looked around in retail shops; bought a pair of rock shoes; and hung out at the UW climbing rock learning moves and techniques.

That summer Johnston called Cauthorn, saying, “I want to start this rock-climbing gym, and I want you to be a part of it,” offering him 15 percent (of what he says was then “nothing … like offering you 15 percent of this glass of water”) and a salary to run the place and bring in rock climbers. Johnston rented a warehouse in Seattle, bought lumber, and at the end of each day’s work as a paralegal would go see how the early members—Cauthorn, Greg Child, Greg Collum, Cal Fulsom and Tom Hargis—were doing in putting the place together.

“I’d stop in and say, ‘That’s kind of crazy—good job,’” Johnston says. “I think we spent $14,000 to build that gym.” He laughs. “That doesn’t even pay for a day of construction on my jobs now.” The original Vertical Club opened in 1987 as this country’s first commercial climbing gym.

“It was definitely a community effort,” Johnston says of the “VC.”

The crew glued rocks onto wooden walls and hung Macrotiles, the textured 18-square-inch hexagonals from Metolius, on one wall.

“We couldn’t get handholds,” Johnston says. “Entre-Prises was making holds in Europe but wasn’t yet selling them in America.”

Cauthorn, though, saw early holds from Brooke Sandahl of Metolius, a good friend and climbing partner. “We got some, and then more and more and more,” Cauthorn says.

“The first holds,” says Sandahl, “were pretty crap, painful and with varying textures … Once we got the mixes more dialed and spent more time on the actual holds, better radiuses and more comfortable grips followed.”

Sandahl and Doug Phillips had shaped most of the early holds, with Grover making the molds. The company’s sponsored athletes Jim Karn and Scott Franklin created later handhold lines. Franklin was the first American to climb 5.14, repeating To Bolt or Not To Be, at Smith Rock, while Karn in the late 1980s and early 1990s climbed more 5.14s than any other North American.

Sandahl calls an open attitude “in showing anyone/ everyone how we made the stuff” key to evolution and use. He walked Boone Speed, Chas Fisher and other climbers through the shop; Speed was to co-found the influential hold company Pusher, and Fisher was founder and president of Bolder Holds/ Straight Up, another pioneering business.

***

John Syrett’s trajectory was brilliant, with a spate of hard first ascents, but tragically short. At a drunken party, he severed two tendons in his fingers opening a beer can with a knife, and never recovered as a climber. He was a binge drinker, and deeply troubled by the death of a coworker on a North Sea oil rig.

As Steve Deane wrote on the blog footlesscrow, “He blamed himself despite being officially cleared of any responsibility. The gradual retreat into solitude, alcohol and periods of depression, already well advanced, now worsened.”

Magnanimous to others, he was a harsh judge of himself. One night he turned up at the home of Pete Livesey, a friend and rival, with a backpack full of whiskey, and they drank and talked for hours. Then Syrett walked 10 minutes to the top of Malham Cove, spent the night on the Terrace Wall Ledge, located near one of his finest climbs, Midnight Cowboy, and, early in the morning, jumped. He was 35.

He left us with much. The British climbing historian Mick Ward, for one, traces much of modern hard climbing history back to plastic, Leeds and Syrett. He writes on UKClimbing: “Let’s take some current limits of rock climbing: the first [French grade] 9a, the first F9c, the first F9a onsight, the first and second free ascents of the Dawn Wall [Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson, Adam Ondra], the first solo of Freerider [Alex Honnold].” All the protagonists developed their skills, at least in the early years, on artificial surfaces. Alex spent most afternoons from age ten through his teens at the gym. To that list we add the Three Amigos—Dave Graham, Joe Kinder and Luke Parady—who in the mid-1990s pushed each other in gyms through the cold Maine winters and then established cutting-edge routes worldwide. Graham and Parady met in the climbing gym in eighth grade.

Daniel Woods, once part of a junior climbing team in Boulder, established the V14 Echale in Clear Creek Canyon in 2004 at 15, and later the famous Jade in Rocky Mountain National Park, climbing many V15s and into V16. His friend Paul Robinson, keeping pace from Massachusetts, was to develop hard problems stretching from Bishop, California, to huge swaths of the bouldering mecca of Rocklands, South Africa. A young Ashima Shiraishi learned to climb 5.14+ from within the confines of New York City. Brooke Raboutou, cragging in summer and mostly climbing indoors during the school year, at age 11 became the youngest person ever to climb 5.14b.

The Leeds wall was probably the first such; and Mick Ward traces today’s burgeoning scene back to “one wall, one climber, and one route.” After 1968, the history evolved in increments, with a big boost 15 or 20 years later, and now, 50 years on, in an explosion.