The Last Mexican Glaciers

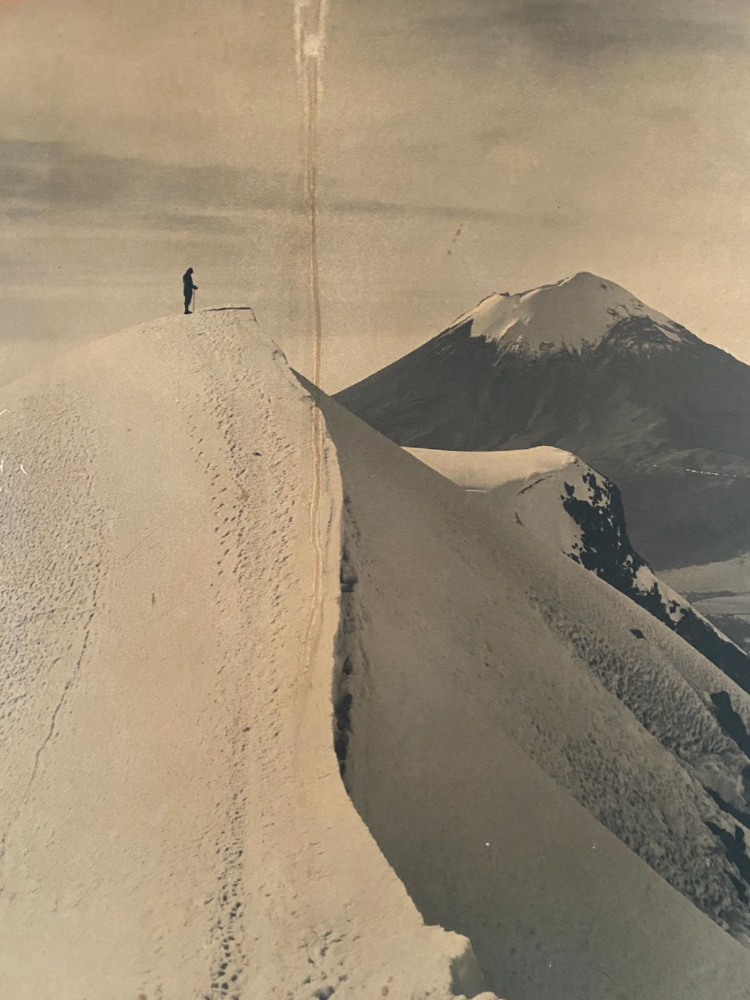

The author, Owen Clarke, on Iztaccíhuatl. (Photo: Gentry Patterson)

The wind was driving hard across the glacier, whipping spindrift into my eyes in staccato bursts. We were at 18,000 feet, high on the summit cone of Pico de Orizaba (18,491 feet), Mexico’s tallest mountain. We had been slogging through over a foot of snow since just above 15,000 feet, where climbers enter a perplexing jumble of boulders and cliff bands known as the Labyrinth. The snow thinned out higher up on the summit cone, but now my crampons scrabbled over hard, slick ice on the 40-degree slope.

I had planned to trek to the summit alone, but given the heavy snowfall, high wind, and shrouds of fog blanketing the mountain, I talked with the sole other climber sleeping at the refuge, an American, David van der Roest, and we agreed it’d be best to stick near each other on our ascent, though we didn’t rope up.

“So much for climate change,” I muttered moronically, leaning hard on my axe and pausing to suck in air, my exhaustion compelling me to momentarily join the company of imbeciles worldwide who use any instances of cold weather as inerrant proof of the “climate change hoax.”

We were climbing in the rainy season and it was a hell of a day to summit, but of course the occasional snowstorm hitting a mountain has nothing to do with the rapid recession of its permanent ice masses.

Orizaba’s glaciers have shrunk as much as 95 percent in the last century, with many no longer existing in any form whatsoever. We aren’t talking about a remaining lifespan of decades though. The glaciers on Orizaba, some of Mexico’s last, will likely be completely gone in a handful of years.

This was why I had come to Mexico, to climb Orizaba before the mountain is irrevocably changed.

***

Mexico historically harbored three glaciated peaks within its borders: Iztaccíhuatl (17,160 feet), Popocatépetl (17,802 feet) and Pico de Orizaba (18,491 feet), the latter also referred to as Citlaltépetl (“Star Mountain,” in the native Náhuatl). Circa the mid 20th century, the trio of volcanoes held a little over two dozen glaciers between them. The vast majority of these are now gone. The glaciers on Popocatépetl (colloquially known as “Popo”) were declared extinct in the early 2000s (a glacier is generally referred to as “extinct” when the ice no longer has enough mass to move under its own weight). Meanwhile, Iztaccíhuatl (Izta) only has one official glacier remaining, with an expected lifespan of a year or two, at most.

Within a year Pico de Orizaba may be the last glaciated summit in Mexico, but even on Orizaba, the clock is ticking.

The day before my ascent, I spoke with Dr. Gerardo Reyes of Servimont, the premier guiding company running trips up Orizaba. His family-run outfit is based in Tlachichuca, a small town of 7,000 nestled just to the west of the mountain, the jumping-off point for most ascents.

Servimont is the oldest existing mountaineering service in Mexico, and Reyes and his family have been guiding on Orizaba and the other Mexican volcanoes for four generations. His grandfather began leading trips up the mountain in 1932. Reyes and his three sons now continue the tradition, with Servimont operating out of a colonial compound that also houses an extensive mountaineering museum, containing a host of 19th-century memorabilia, and, among other items, the first official climbing register for the mountain.

Reyes, who first climbed Orizaba when he was 15 years old, has summited more than 30 times for rescues alone. He’s lost count of the times he has stood atop the peak, but estimates the number at easily more than 100.

The peak is a notable summit, not just by Mexican standards, but internationally. Orizaba is both the tallest volcano and third tallest mountain in North America, after Denali (20,310 feet) and Mt. Logan (19,551 feet). Both Popo and Izta are among the highest mountains on the continent, as well, ranking fifth and eighth, respectively. With the shorter duo of peaks only an hour by car outside of Mexico City, and Orizaba not much further (200 km as the crow flies), all three mountains are extremely accessible for international climbers. (Popo, a notoriously active volcano, is officially closed to climbing. When I summited Izta in 2018, Popo was in the process of erupting.)

Despite their elevation, none of the three mountains require anything more than crampons and a piolet for their standard routes. Though they have minimal crevasse and avalanche danger, rescues and deaths occur every year. Of particular note, a slab avalanche in 1993 killed four climbers. A U.S. embassy staffer was killed on the mountain in 2018.

Reyes noted that the majority of accidents are a result of sheer inexperience, however. The mountain attracts many novice climbers, and often individuals with no climbing experience whatsoever. “People come here thinking it is a hike and try to go without a guide,” he said. “They don’t know how to self-arrest, they aren’t roped up, they don’t know basic glacier technique.”

In recent years, there has been concern online about crevasses opening on the mountain due to the melting glacier. But from talking with Reyes and based on my own experience, it seems these concerns are overblown assuming one stays on route and climbs from the north. (That said, the mountain is changing, so always use caution if attempting a summit alone.)

One of the benefits of Orizaba is its relative accessibility, despite its elevation. Unlike other popular trekking peaks such as Kilimanjaro, there is no costly permit or any red tape to climb Orizaba. One can fly into Mexico City alone on Thursday with a pack, crampons, and an axe, take a bus out to Tlachichuca (which sits at 8,000 feet), climb the mountain, and be back for work on Monday. Servimont recommends unacclimatized climbers take five to seven days for an attempt, but the trek itself can easily be done in six to 10 hours from the hut at Piedra Grande (13,900 feet), which is reached by 4×4.

While it’s true that Orizaba sees scores of climbers during the traditional trekking season (November to March), one can summit the peak year-round, and the off-season offers a decidedly different experience. Aside from David, whom I met at the hut, I was alone on the mountain in mid-May.

Given that all three mountains are several thousand feet higher than anything in the contiguous United States, they offer a unique opportunity for aspiring North American mountaineers to trek at high altitude on snow and ice without having to deal with any technical pitches of ice or rock, and without having to shell out thousands on an international expedition.

All told, Orizaba is one of the most affordable, accessible high-altitude mountains in the world, particularly for U.S.-based climbers. It also offers a relatively safe opportunity to climb a glaciated peak at significant elevation alone, with mellow route-finding and minimal crevasse danger. Sadly, Orizaba won’t be Orizaba as we know it much longer.

***

According to a National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) study published in 2015, Orizaba’s glaciers shrunk 90 percent from 1958 to 2001 alone. Of the original nine glaciers on the mountain, only two remain, according to Reyes.

The once-massive Jamapa Glacier, for which the standard route on Orizaba was named, no longer exists at all. Izta isn’t far behind. University of Zurich glaciologist Christian Huggel told Reuters in 2007 that Izta’s glaciers have shrunk 70 percent since 1960, and that decline has only continued in the 14 years since, with upwards of 50 percent loss of glacial area between 2003 and 2019 according to an AAR study (see below).

Though the standard glacier route is a mere trek, the mountain used to hold a handful of more technical sections, including a 10-pitch WI3 The Serpent’s Head. None of these routes have formed in recent years.

In as little as five years, said Reyes, “Orizaba will be a rock climb.” By his estimate, the remaining two glaciers on the peak won’t just be technically “extinct,” but completely gone from the peak in 10 years, at the most. “It’s just too late,” he said. “Human development is continuing. There are no measures ecologically that can reverse it fast enough. The surrounding forests are burned each year, there are a lot of cattle and sheep around the mountain, without any control. There are no programs to extend the forest to lower levels to help attract or keep humidity and cool temperatures [on the mountain].”

“When I began climbing Orizaba as a teenager,” he said, “from the base camp (13,900 feet) we would reach the edge of the glacier in an hour. Then you put your crampons on and go to the summit. Now, it takes four to five hours to reach the edge of the glacier.” The depth of the glacier has shrunk to a quarter of what it once was—it is now only 10 feet deep in many spots, if not less, Reyes estimated. “The glacier has left the moraine in very bad condition,” he added, exposing treacherous fields of scree and talus. “It’s impressive how fast we are losing it.”

While the number of American climbers has remained steady of late, Reyes noted that the number of European climbers attempting Orizaba has dropped dramatically in recent years (pre-COVID). He is unsure of the cause, but surmised it could be because the worth of an Orizaba summit may have changed in the eyes of some, due to the decreased glaciation.

There are a number of theories as to the glacier’s shrinkage, most obviously the overall warming of Earth’s atmosphere, which is hitting equatorial regions harder and faster. An extensive 2019 study published in the journal Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research noted summit temperatures on both Izta and Orizaba are now at or above melting points regularly throughout the year. In addition, “the atmospheric transport of air pollutants from the Mexico City basin is correlated with the retreat of the glacier, and it is possible that pollution plays some role in glacier loss,” the study noted. According to the study, the peak’s Occidental and Suroccidental glaciers, which once extended down to an altitude of 4,930 m (16,175 feet), had receded up to 5,310 m (17,421 feet) in 2019. The researchers also found that the Glacier Oriental lost over 50% of its mass between 2003 and 2018.

Instead of snow, rain is now the primary form of precipitation on the mountain at increasingly higher elevations, even above 16,404 feet. Hilario Aguilar, then president of the Mexican Alpine Club, noted in 2015 that this has a dramatic effect on glacial erosion. “Years ago when it rained it appeared at four thousand meters, and now little by little the level of rain has risen, and downpours are falling on the summit instead of snow,” he said in an article published by the Mexican newspaper Municipios.

Not only are Orizaba and Izta’s glaciers the only ones remaining in Mexico, the AAR reported that they’re also “the only permanent ice masses at this latitude (20 degrees N)” anywhere in the world.

***

What’s happening in Mexico is not unique: Glaciers are disappearing worldwide, especially fast on equatorial peaks like Orizaba. The consequences reach far beyond climbing, though.

On the approach to the climbers’ hut at Piedra Grande, we passed several bone-dry creekbeds, despite this being the “rainy season” in Mexico. The now-extinct Jamapa Glacier represented a source of water for many communities in Puebla and the neighboring state of Veracruz, feeding the eponymous Jamapa River, which goes on to empty into the Gulf of Mexico south of Veracruz. Its loss has had a catastrophic effect on the water supply for these communities, as well as numerous dependent ecosystems, with local leaders estimating major water shortages will occur within the next 20 years as the remaining glaciation on the peak continues to shrink. “The retreat of such glaciers could cause the loss of microbial diversity that is endemic to these environments,” noted the AAR report.

The loss of Orizaba’s glaciers is a tragedy for everyman mountaineers worldwide. Most peaks at this elevation are incredibly costly and inaccessible for the average individual. Either they’re deep in the backcountry, dangerous, require a wealth of technical knowledge and equipment, have costly permits and guiding requirements, or all of the above.

Picking my way up the glacier to stand on the rim of Orizaba’s caldera, a quilt of clouds strewn out below, blanketing the horizon on all sides, the entire summit covered in snow and ice glistening under the dawning sun… It was an incredible moment.

The next generation of climbers, unfortunately, will have a very different experience on Mexico’s tallest mountain.