Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

Hewett cleaned the device and continued to the ground, knowing from the magnitude of the fall that there was no hope, but moving quickly nevertheless. He reached Skinner’s body some 20 minutes later in the talus at the base of the wall, and then waited, in shock, with his friend. After an hour, Hewett concluded that nobody was coming and hiked out to the Bridalveil Falls trailhead. Here, he called the rangers around 4:30 p.m.; they responded in minutes, along with YOSAR.

The belay loop was found the next day “in vegetation at the base of the wall. It was very worn at the spot where the break had occurred,” according to an incident report posted at nps.gov (an investigation is pending). All this, of course, begs the question, how could such a thing happen?

“A normal belay loop doesn’t fail,” says Hewett emphatically. “It was totally preventable.”

To wit: On October 19, while they racked up, Hewett had noticed Skinner’s leg loops looking worn out, as well as Skinner’s belay loop, which he says was “15 to 20 percent” frayed. “I very much stressed to him that that’s not good,” says Hewett. “Todd said, ‘You’re right. I’ve got a new harness on the way.’”

They discussed the worn harness, talking about how people back up the belay loop with a tied sling, but neither considered it a significant safety hazard. “The belay loop must have got a lot worse over the next few days,” says Hewett, adding that Skinner had belayed him on it with no problems (they spent four out of the next five days working the route). “We didn’t talk about it again.”

Hewett surmises that the belay loop continued fraying due to intensive wall work. He says that Skinner had his two ascenders girth-hitched directly into the loop, the higher one connected via an arm’s-length sling; the lower was attached to an aider, with a similar-length sling girth-hitched around the loop. Hewett speculates that the action of these against the loop while jugging wore it in one spot, perhaps not visible to Skinner under his leg loops.

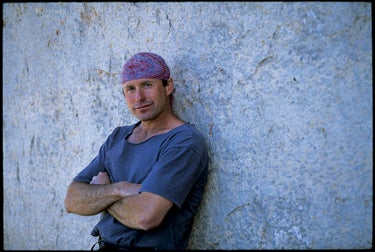

Skinner was a larger-than-life character known as much for his strength, drive, and talent as for his open heart and open door. He is survived by his wife and climbing partner, Amy Whisler Skinner, and their children: Hannah (8), and twins Jake and Sarah (both 6). Friends and family held a well-attended (500-plus people) celebration of Skinner’s life in Lander, Wyoming, on October 27 — what would have been his 48th birthday.

—Matt Samet

The Life and Climbs of Todd Skinner

By Steve Bechtel

Todd and I had been walking in the rain and dark for hours. We’d failed again on a weekend trip to climb a wilderness wall in the Wind River Mountains and were heading out of the backcountry late on a Sunday. My headlamp was starting to fail, and Todd’s was so weak he had to hold it in his hand to see the ground. We stopped briefly under a somewhat dry group of trees, and Todd said, “Well, we’re lucky men.” “I don’t feel very lucky right now,” I said. “At least we’re not accountants,” he replied, cracking a classic Skinner smile.

Todd Skinner, 47, was raised in Pinedale, Wyoming, and gained the adventurer’s spirit early in the Wind River Mountains. It was here, where his father and four uncles ran the Skinner Brothers Wilderness Camps, that he was introduced to the sport. However, he didn’t take an interest in hard rock climbing until he entered the University of Wyoming in 1977, when he met longtime partner Paul Piana, who showed him how really to climb. Todd graduated college in 1982 with a degree in finance, and then planned to “take a little while off to climb” before settling into a real job. Those few years turned into the rest of his life.

He began his travels in the United States and Europe, mastering the hardest routes of the day, including the Shawangunks’ Supercrack (5.12c), Buoux’s Chouca (5.13c), Grand Illusion (5.13b) at Sugarloaf, California, and adding several of his own, including Yosemite’s The Stigma (5.13b). He was the first American to flash a 5.13 (the strenuous crack Fallen Arches, in Utah) and established Throwin’ the Houlihan (5.14a) at Wild Iris, Wyoming, in 1991 — the first consensus 5.14a put up by an American to hold the grade. In 1988, after three years of effort, Todd and Piana made their groundbreaking free ascent of El Capitan’s Salathé Wall (VI 5.13b), ushering in a change in attitude toward what could be done on the big walls of the world. Famously, the pair survived—after their epic, nine-day free push—an accident on the summit on June 16, 1988, when a block to which they were anchored slid over the lip, nearly taking them with it, breaking Piana’s foot and several of Todd’s ribs. Todd later went on to score such big-wall coups as the razor-cut arête of The Great Canadian Knife (VI 5.13b; 1992) on Mount Proboscis, Canada, again with Piana, and the Cowboy Direct to the Swiss-Polish route on the east face of Nameless Tower (20,623 feet) in Pakistan—checking in at VII 5.13a all free, in 1995.

I was fortunate enough to accompany Todd on four of his big trips. His phone call to me from Yosemite in 1993, while he was working the Direct Northwest Face (VI 5.13d; then 5.10 A3) of Half Dome, forever changed the direction of my life. “Hey, Steve, Todd here. This is the call,” he said, rallying me for the charge. His enthusiasm for this big, new free line led me to quit my job on the spot and head to California. From the heinous 5.13 slab pitches at the bottom of the climb, to the soaring dihedrals of the upper wall, to topping out among some dozen bikini-clad coeds, this route showed me the great ups and downs of hard big-wall free climbing.

In 1990, Todd found what he considered the ultimate training ground—the dolomite cliffs of Lander, Wyoming—and decided to make his home there. It wasn’t just excellent rock and high-quality routes that put Wild Iris and Lander on the climbing-world map, however; Todd’s infectious enthusiasm became the foundation for a vibrant climbing community in this small Wyoming town. He encouraged climbers to visit, started a climbing shop (Wild Iris), and opened his home to all number of travelers and friends. Todd developed easier climbs with the same care and attention as project-level routes, and treated rookie climbers with the same respect as seasoned pros. The result was a community of strong, friendly, and competent climbers.

In 1994 at Hueco Tanks, Todd opened his Hacienda del Fuerza training camp, a wintering ground for the world’s strongest, most motivated boulderers, who’d show up to climb all day then train into the night. Continuing a love of the park that went back to 1982, Todd had merely shifted his focus into the next decade. It was here in 1984 that he’d made the yo-yo first ascent of The Gunfighter (5.13b) after 13 days of effort spread over six weeks, including solo-camping below the climb and coaxing locals (in one case, two kids ditching high school) to belay him. Such was Todd’s dedication.

Entering his 40s, Todd continued to climb at a very high level, even with an increased workload (specifically, his successful career turn as a motivational speaker) and family. He climbed frequently on the dolomite, and in more recent years returned to granite. His primary focus was Sweetwater Rocks, a little-known area 60 miles east of Lander that Todd hoped someday would hold 10,000 routes. Here, he established dozens of new, hard routes, declaring some of them the toughest he’d ever climbed. He had also rekindled an interest in the Wind River Mountains, both for the abundant unclimbed cracks and its proximity to his home and family.

Todd was attempting a new free climb on Yosemite’s Leaning Tower with partner Jim Hewett when he died. He told me, “After this route, I’m done with Yosemite.” My last phone message from Todd recalled one of our recent trips together. He said only, “Stuck on ice slope…crampons failing…send Pop Tarts.”

I will miss his voice on the other end of the phone.

Remembering Todd Skinner

Lisa Gnade:

“When it comes time to die, be not like those whose hearts are filled with fear of death, so when their time comes they weep and pray for a little more time to live their lives over again in a different way. Sing your death song, and die like a hero going home.”—Tecumseh (Shawnee)

That’s a great quote from a book Todd had been reading about which he told Steve Petro … actually the very last time Steve ever spoke with him, at the end of July.

Todd was a friend to all who came as friends. He had a way of making everyone feel welcome. His genuine interest in the endeavors of others and sincere form of encouragement made him a magnetic personality. He loved success in climbing, for others as well as for himself.

We were very lucky to have seen Todd and climbed with him, heard the stories and laughed together a few times recently. Although we’d known each other for 20+ years, it’s always good to stay current with your friends. Todd fixed Steve and I up as a couple 🙂 17 years ago.

Any of us who have ever been sponsored climbers in any way owe a lot to Todd. He was the father of sponsorship in America, as he was the first person to present the concept of sponsorship to the American climbing companies. He provided opportunity for many at the time and for all who now stand on his shoulders. It seems that we often forget to think of how opportunities are provided.

More than the huge inspiration and opportunities he provided, his routes, his point of view, his generosity, his tales, or anything else, I’ll remember that Todd was fun to be around. I can hear him laughing, even now!

Bobby Model:

I spent 60 days camped in a tent … 30 of which were tent bound at a touch over 18,000 feet on Trango Tower with Todd Skinner. I remember after being trapped in a tent during one storm for nine days straight, when the wall above was caked with ice and most expeditions in the Karakoram had left the Baltoro, Todd wrote a quote on our tent wall: “You must kick at the darkness until it bleeds daylight!” It was Todd’s perseverance that got us to the top a couple weeks later. Big-wall free climbers are forever indebted to him for his unmatched determination and the vision that he brought to the sport.

Sometimes I pass through places where I had traveled with Todd and meet the same people we had encountered in the years past … whether it be a Samburu goat herder in the northern district of Kenya or a Balti guide in the Karakoram, the first thing they ask is: How’s Todd? He cared about the people that crossed his path. He always gave more than he took. Never will a day pass that I won’t think about Todd Skinner. His spirit will live on through his wonderful family and children and also through all of us who shared his presence no matter how short or long it was.

Lynn Hill:

I met Todd about 20 years ago when he and Beth Wald were living the life, traveling from one crag to another across the country. Since then, we’ve crossed paths numerous times at various places over the years, including a trip to Vietnam together in 1996. The last time I actually saw Todd was last summer at the Lander International Climbers Festival, where he graciously helped me set up my presentation at the local auditorium. Todd called me this summer as well to invite me and Owen up to the Lander area to go climbing on some “secret” limestone crags located near a cabin, complete with a babysitter and his three kids to help keep everyone happy. Regretfully, I was never able to join them.

But no matter where or what the circumstances, I always enjoyed hanging out with Todd. He was light-hearted, playful and always so enthusiastic and supportive toward everyone around him. It was impossible not to be charmed by his big beautiful smile. Todd came to visit me a few days after I gave birth to my son, Owen, and I was impressed by the amount of love he exuded as a parent and friend.

As a climber, he was a certainly a visionary. He was one of the first climbers to make his lifestyle as a climber transform into a viable career. Todd broke ground with his “avant garde” style and first ascents all over the world from the boulders of Hueco Tanks, to the alpine walls of Trango Tower in Pakistan. His free ascent of the Salathé Wall on El Cap with Paul Pianna in 1988 marked the beginning of the current trend of free climbing on the big walls of Yosemite.

As a public speaker, Todd was gifted. He could make the entire room roar with laughter, and the next moment, at the edge of their seats with excitement, but best of all, he was an inspirational person that left everyone feeling that with enough passion, determination and hard work, anything is possible. The world is a better place as the result of Todd’s passage through it and he will certainly be missed by all of us whose lives he touched.—

Steve Petro:

Todd possessed the energy of two hundred horses.

As a player/coach he would coax results from me that I could not achieve by myself.

He was always more jubilant when I succeeded than when he did.

When I climbed with him, we climbed a lot, but we laughed a lot more.

We would play the trickster game where the person who climbed the pitch first would tell the next climber there was a jug where none existed, or would insist that no holds were out there, when in fact, very good holds did exist.

He enjoyed discussions about strength-training methods, muscle strength, and mind strength.

He wanted to achieve results, but I think he loved striving more. And he despised mediocrity.

Two books he recommended to me were: When Legends Die, and The Power of One. Both are fantastic.

He was a charismatic personality, and like a magnet, I was drawn to meet him in various locations in the West to go climbing.

He understood the art of telling a good story. It was important for his audience to laugh, wonder, wait in suspense, imagine, dream, and feel inspired.

If you weren’t a better person for having spent time around him, then you missed his message.

Randy Leavitt:

A few things stand out about Todd to me even though there are so many places to start. I always admired him for his motivation and enthusiasm. What stands out most to me is that he was such a quality human being. Sure, he got noticed because he was a great climber, but that was secondary to him being such a fine person. Being a great climber doesn’t mean you are a great person. Todd understood this and was both. Todd was also a leader. While most people were crawling around wondering what to do, Todd stood up to see which direction to go. He was a visionary climber and made others around him better. He was like a high tide that lifted all boats.

I can’t believe he is gone.

Tommy Caldwell:

Todd was always a huge inspiration to me. I met him when I was about 12 and a nobody. He always remembered my name. He always showed overwhelming amounts of enthusiasm and got everyone excited in some way or another. It made me mad that many people seemed to focus on the controversy when there was so much more to Todd. I looked up to Todd as a mentor as much as anybody in the sport. I will truly miss him.

Jim Thornburg:

“Todd was such an alive person … it’s hard to imagine.”

Jim Hewitt:

“He would have been putting up new routes for another 25 or 30 years. His energy for climbing was so great.”

Beth Wald:

“Todd was one person I expected to be around forever. I always thought he would end up governor of Wyoming, or at least mayor of Lander.”

J. A. Wainwright:

A Canadian poet and novelist whose work A Deathful Ridge: a Novel of Everest was short-listed for the Boardman-Tasker Prize in Mountain Literature in 1997, composed the following poem in memory of Skinner.

Ceremony for Todd Skinner

Hanging in mid-air

Above a bridal veil

Where sky reaches up

To touch the rock

You tasted grace

On your tongue

For the last time

As a daisy chain

Of webbing snapped

To scatter hawks

Across Yosemite

Like flakes of pain

Or shards of mica

In the wind

Those below

Could only wonder

How high death must be

And whether you imagined

This worn moment

Before the fall

That made your face

The one to climb

The one whose crevices

Of cold desire

Could not hold you

Despite the ring you wore

So the marriage

Might be told