If you buy through our links, we may earn an affiliate commission. This supports our mission to get more people active and outside.Learn about Outside Online's affiliate link policy

[Interview + Excerpt] Stories Behind the Images: Lessons from a Life in Adventure Photography, by Corey Rich

"None"

Corey Rich’s 286-page book of images and the tales behind them represents a deep dive into the mind of one of climbing’s most prolific and talented photographers. It comprises short, self-encapsulated, behind-the-scenes accounts of Rich’s favorite photographs, ones that have become iconic over time and that represent his trademark combination of brilliant light, crystalline clarity, and a reverent sense of place.

The book features everything from the famous (infamous?) Rikki Ishoy cover of Climbing Magazine (No. 173), which was published in 1997, to shots from Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson’s 2015 free-climbing push on the Dawn Wall, to Fred Beckey hitchhiking with his “Will Belay For Food” sign. Rich’s stories are designed to inspire and give deeper context to the images that have helped shape our perception of the outdoors over the past 25 years. Revealingly, he writes about how he didn’t realize how important some of his images would be at the time he took them. Of the Beckey hitchhiking shot, Rich confesses, “When I took this photo, I didn’t really understand at the time just how symbolic it would become. Fred set the bar for what it means to be a dedicated climber, and this photo captures what he represented and still represents to the community.”

Aside from the spectacular images, Rich’s book gives us a deeper look into the technical and logistical sides of climbing photography, covering every aspect of preparing to convey a meaningful and captivating story through the lens. Challenges early in Rich’s career revolved around shooting on film, having at times only a single opportunity to capture the moment before it passed. Later with digital cameras, he’s still faced the dual challenge of simultaneously working with a stills and video camera on top of the logistical tangles involved in multi-day sieges of big walls from Yosemite to Patagonia. The book also delves into the sometimes-harsh, on-the-ground risks and reality of being an adventure photographer, including Rich’s hair-raising yarns about being held at gunpoint at a checkpoint in Mexico, swimming from crocodiles in Indonesia, or nearly rappelling off the end of his rope on El Capitan.

More than a mere chronicle of the expeditions and exploits of a professional adventure photographer, however, Rich’s book details how much he cares for climbing, for adventure, for the culture that surrounds the outdoors and its activities, and for its characters like Fred Beckey, Alex Honnold, Chris Sharma, and many more. Anyone who enjoys captivating imagery coupled with amazing tales of adventure would do well to get their own copy of Stories Behind the Images.

$29.95, mountaineersbooks.org

Available at:

Interview

Why did you decide to write a book in this format instead of a tabletop photo book?

Corey Rich: I just love storytelling. A traditional photo book—nobody reads it; it just isn’t designed to be read. This is a book that’s designed to be read. It’s me telling stories and character profiles of different amazing people, and the lessons I’ve learned over the years. I really wanted this to be a book that you could hold; a book that would fit in your backpack or in an airplane seat in front of you. The point of this book, the goal behind it, was to inspire people to get out there and get after it as well as share their own stories.

What climbing story from the book had the most impact on your life, or the direction your life or career have ended up taking?

I don’t know if there’s any one climbing story. It was meeting people 25 years ago who became lifelong friends and industry leaders that inspired me. I really tried pouring my heart into all the essays.

What advice do you have for aspiring adventure photographers and videographers breaking into the industry now, versus when you got your start a quarter-century ago?

I think the most important part is, the image is still key. It all comes down to the question of are you making great pictures? There are a lot of good pictures out there; there are still very few great pictures. I’ve been at this for 25 years, and I have only a few great pictures. I have a lot of good ones, but only a few great ones. It’s that pursuit of trying to make that great image. It means pushing hard all the time—getting up early, staying up late, working harder. Sometimes I hear aspiring photographers spend way more time talking about the business of photography than the actual photos themselves. That’s just a necessary evil. Spend 95 percent of your time making pictures and striving for great.

Do you think it’s easier or harder now than it was back then to make a living as an adventure photographer?

I think it is easier today, for sure. It’s just a bigger market today than it was 25 years ago. The scale of the industry has outpaced the scale of photographers. Every major city has three climbing gyms in it now; REI has 156 retail stores; and, I mean, climbing is in the Olympics in Tokyo! I could never even have imagined 25 years ago that our market would be this big. We are living in the most exciting time ever for content creators. We now have control over publishing our own content. The playing field has never been more level; there is no longer the cost of entry that we had with film. It’s a pretty exciting time to be embarking on a journey of adventure photography.

As a photographer, you have traveled all over the world. Where is one place you hope to visit again soon? What is the one place where you’ve shot that feels most like “home”?

California. I live in Lake Tahoe, but I like to say I live in the Sierra Nevada Mountains, which is inclusive of Yosemite, the Needles, Dome Rock, and so much good rock. I just have a huge grin on my face every time I pull into the Tahoe Basin. That being said, Alaska is one of the most rad places on the planet. I will be going back many times over my life. Also there are the Karakoram Mountains in Pakistan—I’ve never seen a mountain range like them before. They are the wildest, raddest mountains on the planet.

It seems throughout your book that big walls, and El Cap in particular, hold a special place in your heart. What draws you to these features and makes them so entrancing to shoot?

Having that amount of space as a photographer is wonderful. The big, sweeping backgrounds and vertical depth give me maximum creative flexibility and a chance for longer, more authentic stories. I love shooting bouldering and the hardest 10 moves of all time, but there’s a limit to the beginning, middle, and end of that story. On a big wall, there’s that grandeur and expanse and that duration of time that [allow] for fruitful visual storytelling opportunities. Big walls force a journey.

Tell me a bit about the logistics of rigging a big El Cap shoot—how long your ropes are, what they weigh, how you get all that equipment up there and get rigged (safely), etc. I think most people probably have no idea how involved, complicated, and sometimes risky it is.

It’s changed a lot in my career. I would show up three days before a shoot with 12 ropes, carry them all up the back side of the wall, [and] slowly start rappelling in. Then, as I would shoot the pitch, I would throw the excess rope off. Then, after the shoot, I would have to hike through the talus field trying to find all of my ropes. It was this monumental effort. Now I’ve matured and grown up, and more often than not now it’s a team of us rigging. We set it the day before with much more skill and more manpower. Much less bumbling. And the other way we sometimes do it is we have two parties. We have a party of badass climbers putting the ropes up for me so I can hang in the right spot above the climbers I am capturing.

How long did it take you to write this book?

Rich: You know, I never intended it to be a book. I started doing these essays on a blog and on social media, and after looking back over them all I realized I was sitting on a book. Once we sat down and decided that we were making the book, it probably took about two years to get the printed copy in hand.

What was the biggest revelation you had about your work, or yourself, while writing this book?

Rich: The biggest revelation was that I have zero sense of time. Everything feels like it was just a few years ago. I’ve just been having a blast, and it makes the time fly by. It’s been a damn good journey.

What do you hope this book conveys to its readers?

More than anything, I want people to be inspired—inspired by the stories in the book. And I hope the book pulls back the curtain on who the people are in the stories and what drives them—and to some degree pulls back the curtain on myself as well, for those aspiring to be photographers or storytellers, on how I stumbled into a career where I feel I haven’t worked a day in my life because I love what I do so much. I just want to move people.

What is your singular favorite image from the book?

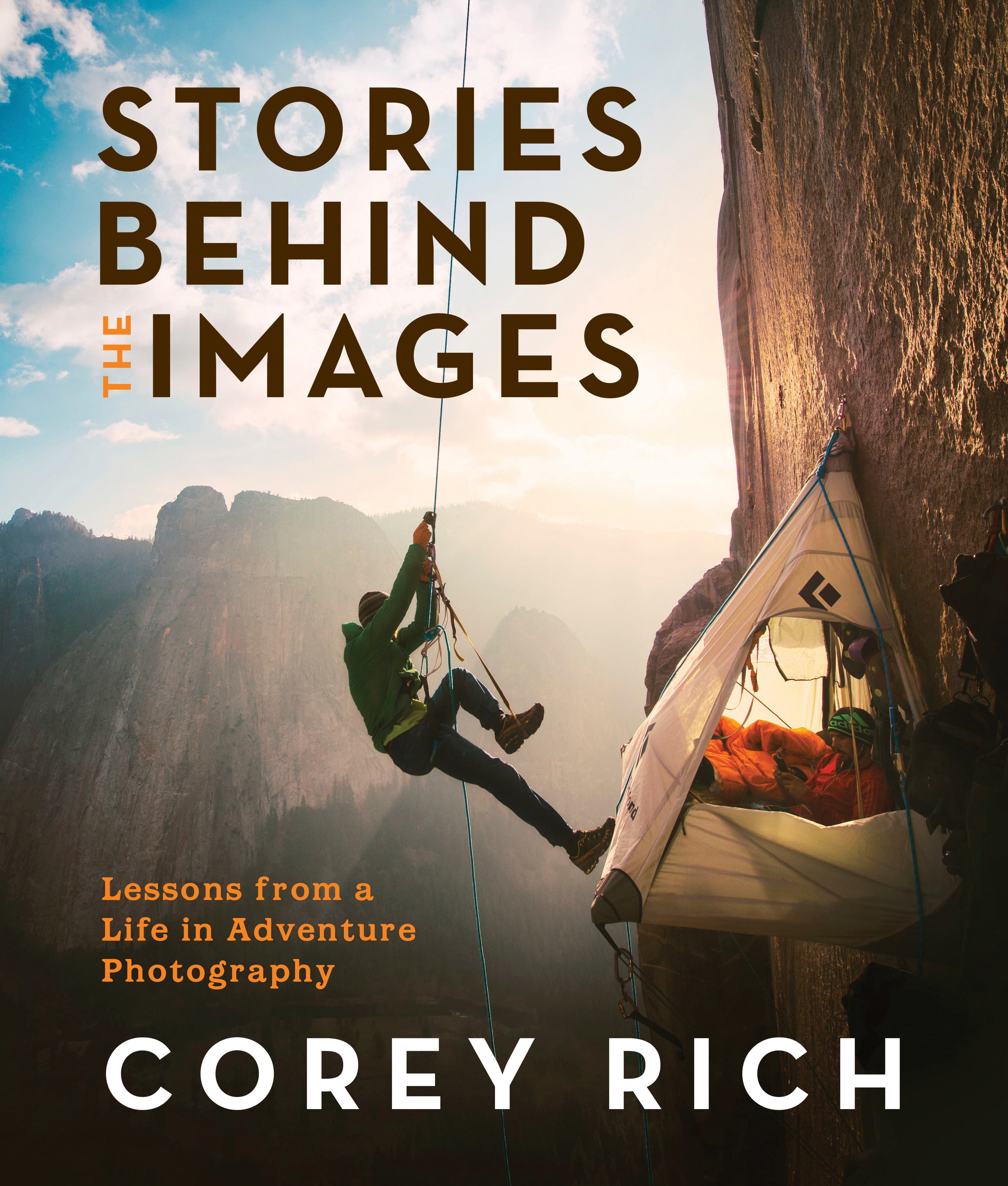

Rich: It’s probably the cover [the photo of Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson on the Dawn Wall]. It epitomizes what I love about photography and climbing. That experience being up there with them was amazing. It’s a meaningful story: The moment was right, the light was right—it was exposed right—and I got it all in focus as well. It encapsulates why this career has been so fulfilling for me. Attached to that photo are so many stories and memories. And it’s a good photo, maybe even bordering on great.

Excerpt

The following is excerpted with permission from Stories Behind the Images: Lessons from a Life in Adventure Photography (Mountaineers Books, October 2019) by Corey Rich.

I took this picture of Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson at 3:59 p.m. on January 11, 2015. At this point, I’d been living on the side of El Capitan alongside these two climbers for ten days, documenting their efforts to make history and complete the long-awaited first free ascent of the Dawn Wall, a 3,000-foot route that was subsequently dubbed the hardest rock climb in the world.

I don’t know what it was, exactly, but the Dawn Wall story gripped the interest of people around the world in a way that I’d never seen before. Rock climbing in general is an obscure activity/lifestyle that is understood by few. But for a couple of weeks in January of 2015, climbing exploded with mainstream media attention. It was incredible!

As a longtime climber and climbing photographer whose roots are deeply embedded in this small niche world, the Dawn Wall media extravaganza was a spectacular thing to behold. Of course, I was honored and humbled to be part of the team—which included my good friends Brett Lowell, Bligh Gillies, and Kyle Berkompas, among others—that helped tell this story to the public through pictures and video.

I was also interested to see that this photograph, with Tommy ascending the rope and Kevin in the portaledge, preparing to climb, was the one that received perhaps the biggest response of all the photographs I took during the ten days I lived on the wall.

What’s so fascinating to me about this photograph is that it’s not a core rockclimbing picture. From a climbing perspective, nothing particularly extraordinary is happening. In fact, this could just as easily be a photo of any two weekend warriors from San Francisco.

Yet it was this picture that went viral on National Geographic’s Instagram feed, graced the covers of newspapers, hit the cover of a special issue of Time magazine, appeared on television news networks around the world, and even appeared on the cover of Rock and Ice magazine’s special Dawn Wall issue. Essentially, something about this photo touched both the core climbing community and the world at large.

When I look at this picture, I can’t help but recognize that it is deeply inspired by one of my climbing and photography heroes: Tom Frost.

Tom Frost, who passed away at the age of eightytwo in 2018, was a friend, mentor, and total badass in both the climbing and photography worlds. He was also one of the humblest guys around. Photographers may know him as a cofounder of Chimera Lighting, based in Boulder, Colorado. But Tom was also a climbing pioneer during Yosemite’s golden age.

Tom began climbing in Yosemite with the Stanford Alpine Club, and graduated from the prestigious university in 1958. That same year, climber Warren Harding completed the first ascent of El Capitan via the Nose. In 1960, Tom became part of the team that made the second ascent of the Nose.

Tom went on to complete two more noteworthy ascents of El Capitan. In 1961, he joined up with Royal Robbins and Chuck Pratt and achieved the first ascent of the Salathé Wall, El Cap’s second route.

In 1964, this same trio as well as Yvon Chouinard completed the first ascent of the North America Wall over nine continuous days. This was considered El Capitan’s most difficult climb to date.

Tom’s background as an inventor, engineer, and businessman came together in 1972 when he and Chouinard founded Great Pacific Iron Works and started to manufacture climbing gear. This company would ultimately give birth to both Patagonia and Black Diamond Equipment, the successful apparel and climbing-gear companies that we now know today.

While all of these achievements in and of themselves constitute a most envious curriculum vitae, the reason that Tom Frost stands out to me is because his skills as a climbing photographer are, in my mind, unmatched. In fact, he might have been the most naturally talented, and unsung, adventure photographer in the world.

You’d be excused for not knowing any of this, though, because Tom was one of the most down-to-earth guys you’d ever meet. Humility, it seems, is a characteristic that is common to many people who are truly great El Cap climbers—Tommy Caldwell, I’m lookin’ at you!

For example, I only learned about Tom Frost’s extraordinary photographic skills in a most unusual and unsuspecting way.

As a former owner of the Aurora Photos stock photography agency, I have spent a lot of time over the years reviewing pictures from the top outdoor-adventure photographers. I live, eat, and breathe adventure photography. So it’s rare that I come across a photographer who really blows me away with his or her raw talent or entirely new way of seeing things.

So rare, in fact, that it’s happened only once.

Several years ago, I approached Tom with the idea for him to become a contributor to Aurora Photos, archiving his photographs to make them available to future generations in a searchable online database. He was excited about the idea, so I made the five-hour drive through the Sierra foothills to his home in Oakdale, California. Tom and his wife, Joyce, welcomed me, fed me, and wanted to hear all about my travels, adventures, business, and love life (I had just started dating Marina, now my wife).

After catching up, it was time to get to work. With loupe in hand, ready to edit, Tom led me to his desk, where he had a light table ready. His shelves were lined with film-filled binders. The negatives and contact sheets were meticulously organized—numbered and arranged by date—which clearly speaks to Tom’s mind as an engineer.

I grabbed binder number one, roll number one, and began looking at the contact sheets, occasionally checking the negative to see if the image was sharp. Some of these images were marked with a grease pencil, and I recognized them as iconic photographs of Yosemite’s golden age. But in between those more recognizable shots were other pictures that I found to be just as fantastic, if not better.

It felt amazing to be looking at what is arguably rock climbing’s most important moments—its very genesis as a modern adventure sport—while one of the very founders himself sat right beside me, recounting one incredible story after another behind each and every frame.

I couldn’t believe what I was looking at. Roll after roll, each negative was unique. There were no motor-driven sequences, fired in the hopes that one frame would be in focus and show a decisive moment. Tom had shot no more than a frame or two per scenario—but he had always nailed one. That shot was invariably perfectly exposed and composed, capturing a wonderful decisive moment and telling an incredible visual story about the character and spirit of Yosemite’s earliest climbers.

I was impressed with his level of technical proficiency and obvious understanding of photojournalism— of using his camera to tell a wonderful story with each shutter depression.

I had become completely engrossed in poring over this archive—so engrossed, in fact, that I didn’t realize that hours had passed.

“Corey, let’s take a lunch break,” Tom suggested. Reluctantly I put my loupe down, and Tom and I went to a nearby Mexican restaurant for some burritos, another passion we both share.

We talked about business and big-picture ideas, but I was really keen to grill Tom about his photographic background. Where had he learned how to use a camera? What was this extraordinary photojournalistic background that drove him to capture the original founders of our sport with such expertise, skill, and creativity?

“How long had you been shooting before you began documenting Yosemite climbing?” I asked Tom. “I started on roll one today, but obviously that’s just your climbing archive. Tell me about your photography experience before that.”

Tom’s response was one of confusion.

So I clarified myself and asked again, “What had you shot before this?”

With the deadpan tone that any engineer uses to deliver facts, Tom simply stated, “That binder you started with today—number one—that was the beginning. That was my first roll.”

“What?”

I would’ve fallen out of my chair except for the fact that we were both sitting in a booth. Most people spend a lifetime trying to master the art and craft of photography, but Tom’s keen eye and raw talent were evident in his very first roll of film.

“It was 1960,” Tom explained, “and I was standing in Camp 4 with Chuck Pratt and Royal Robbins. We were racking up for what would be the second ascent of the Nose. Then Bill Feuerer comes over and just hands me his Leica camera. And he says to me, ‘Hey, Tom. Take this up with you. You’ll want it.’ So that’s how it started.”

To become familiar with the camera, Tom shot his first scenario, creating the now-iconic image of Royal and Chuck sorting pitons on a Camp 4 picnic table as Bill looks on.

“I was no photographer or photojournalist,” Tom said humbly. “I was just a climber who carried a camera.”

This was where it all began. Not only had Tom pioneered Yosemite big-wall climbing, but he’d also pioneered adventure photography. In the photography world, I had never seen such raw virtuosity and talent, before or since.

In light of the Dawn Wall media extravaganza, my main takeaway has been one of feeling grateful to be able to stand on the shoulders of Tom Frost—and many others who have since followed in his footsteps—and document an exciting moment in Yosemite’s incredible climbing history.

There’s also a parallel with Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson, in that their achievement is also the result of the pioneers who paved the way for big-wall free climbing before them: the Huber brothers; Paul Piana and Todd Skinner; Lynn Hill; Max Jones and Mark Hudon—all the way back to Tom Frost, Royal Robbins, and Chuck Pratt.

In Ascent magazine, Tommy once wrote: “Embracing all styles of climbing made me the climber I am today. Style is a body of knowledge and a collective, generational work in progress. Nowhere is this truer than in big-wall free climbing.”

The same could be said of photography: that it’s a generational work in progress. This image that I took of Tommy and Kevin on the Dawn Wall isn’t mine, per se. It belongs to all those photographers who came before me and have inspired me over the years, including Glen Denny, Galen Rowell, Greg Epperson, Jim Thornburg, Beth Wald, Brian Bailey, and Bill Hatcher. And it belongs to all those who’ve come up since: Keith Ladzinski, Tim Kemple, Jimmy Chin, and Andrew Burr—among dozens of others who have simply been, in Tom’s own humble words, nothing more than climbers with a camera in tow.

Today, the Dawn Wall is considered the hardest big-wall free route in the world. But tomorrow, there will be some new, stronger climbers who will climb it more quickly and in better style. (In fact, two years after Tommy and Kevin’s ascent, Adam Ondra, a young climber from the Czech Republic, managed the second ascent in rapid style.)

The same phenomenon is true with adventure photography. We are all standing on the shoulders of those whose hard work and fresh creativity came before us. And it’s our duty to stand as tall as we can, push the limits as high as we can, and wait to see what incredible climbs and visual storytelling tomorrow generations will bring.