Recall This: The Real Danger Behind Climbing Gear Recalls

"None"

This story originally appeared in the May 2016 issue of our print edition.

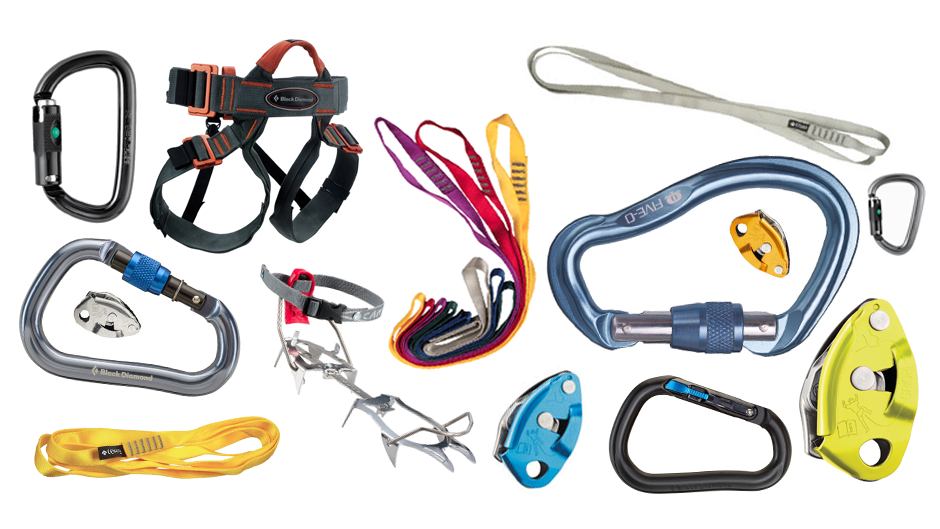

Earlier this year, Black Diamond announced a voluntary recall of 14 styles of carabiners and two styles of slings. The pins in the carabiners had been improperly riveted, and the slings had a tape splice. The recall sent a wave of panic through the climbing community.

“This is gear that if it doesn’t work as advertised can KILL SOMEONE!” wrote a climber with a malfunctioning caps lock button on the Black Diamond Facebook page. Climbing gyms plastered the BD recall notifications on their walls, climbers shared them on social media, and the Internet forums all suggested a serious problem. Climbers do, in fact, trust gear with their lives, so the knee-jerk reaction was not surprising. However, gear recalls and the resulting commotion distract consumers from a bigger issue: the lack of personal responsibility.

Although zero accidents were reported, Black Diamond, who declined to comment, in conjunction with the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC), issued a recall. Started in 1972, the CPSC regulates the sale and manufacture of products that could pose a hazard. On average, the CPSC reports 300 recalls a year, everything from pizza cutters that detached during use to a Darth Vader onesie that posed a choking hazard to infants. In the past 20 years, there have been only 30 mountain climbing product recalls by the CPSC. All the reports show that products have failed during use, like crampons breaking while kicking steps, but there have not been any CPSC-reported injuries. Most recalls are preventive measures.

“What you’re really after is to ensure the safety of your customers,” said Metolius President Doug Phillips, a veteran climber and manufacturer who has dealt with several recalls. “You’d much rather be on the safe side than on the other side, where maybe we could just let this go and not have to deal with it.”

Recalls have three levels: safety alerts, voluntary recalls, and involuntary recalls. Safety alerts request consumers to inspect products, possibly repairing or sending damaged goods to manufacturers for replacement. Voluntary recalls ask consumers to send the product to the manufacturer for replacement or repair. Involuntary or compulsory recalls occur when the product is such a hazard that the government forces the company to recall the product because of injuries. The majority of climbing-related product recalls have been safety alerts with a few voluntary recalls.

“The cost of a recall will vary by type of product, the quantity, how far the product was shipped, and what the remedy is to the hazard,” said CPSC spokeswoman Kim Dulic. The product replacement, shipping, and the man-hours required for recall-related inspections add to the real-dollar cost, but perhaps the greater cost is the one to the manufacturer’s image.

“At the core of this issue is the corporate mandate of ever-increasing sales and profits, which functionally undermine product quality and, in this case, safety,” wrote one online commenter. The angry Internet fodder and a general unease can negatively affect sales, but the bottom line is that despite the high cost of recalls, the liability for corporate negligence costs more. The cost of a recall ultimately becomes second to safety. Plus, the majority of gear manufacturing employees are climbers themselves and understand the level of trust between a climber and her gear.

“I don’t even know how much our products cost,” said Rick Vance, a climber and Petzl America’s technical director. “I have to make all my decisions based on risk, as opposed to a business decision.” Vance assisted with the highly publicized recall of the Grigri 2 belay device only months after it hit the market. In August 2011, Petzl voluntarily recalled 18,000 Grigri 2 units because it was possible for the handle to get stuck in an open position, preventing the camming unit in the device from doing its job to stop the rope from moving through. This particular defect was discovered when a military group attempted to haul a Humvee out of a ditch. Although this example is at the extreme edge of the device’s capabilities, it created a strong enough argument for Petzl to make a recall. To encourage customers to replace the product, Petzl offered free shipping, and the company received more than 80% of the defective units. The standards for climbing product recalls are quite high, as the companies have a large sense of responsibility.

“Scary to think gear with more moving parts like a cam or ascender could have manufacturing errors and that you didn’t catch them,” wrote one climber. Complicated climbing products, like the Grigri 2, have far fewer recalls than the most-used item in climbing. Carabiners, which are involved in nearly every climbing action, are the most produced climbing product, and they require the most attention.

“Carabiners hold all these systems together. They need to be right,” said Vance. “It doesn’t take much to be wrong with one for it to reach that point where we say, ‘That’s a big problem.’” In 2006, Petzl voluntarily recalled 8,000 ball-locking carabiners because the gate could fail to automatically close, changing it from a triple-locking carabiner to double-locking. In 2011, Camp voluntarily recalled 15,500 Photon carabiners because the gate could open under a heavy load; Wild Country recalled 1,000 Helium carabiners in 2004 for a similar reason. That same year a gear shop employee spotted faulty pinning in a Metolius carabiner. When all was said and done, only six out of 80,000 carabiners had improper pins.

“You mean I can’t duct tape two ends of a sling and call it good?” joked one climber in response to the Black Diamond sling recall. The bigger question surrounding gear is one of personal accountability; all climbers should know the proper function and uses of each piece of gear.

Since the first car-axle pitons in the 1950s, the production quality of climbing gear has increased exponentially, but that also means individuals have moved away from inspecting their own gear. Recalls can cause a panic because it reminds us that climbers shouldn’t put blind faith in equipment, something we’ve become accustomed to. All climbing products come with a warning label reminding the consumer that climbing is inherently dangerous and that they need to be aware of a product’s capabilities. Many climbers rip these tags off without ever reading them. While manufacturers have a strong responsibility to produce the highest quality gear, accidents can be avoided when individuals take personal responsibility for their climbing equipment.

“It just seems that the generally accepted thing today is to take it straight from the store and start using it without really inspecting it thoroughly,” said Phillips. “It’s really difficult for a manufacturer to say, ‘OK, the first thing we want you to do is to look really carefully at our stuff and make sure there’s nothing wrong with it.’ But it’s just a really good practice.” An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure, as the adage goes. “You could look at climbing gear your entire life and never find anything,” said Phillips. “But on rare occasions, someone will find something and that’s when we like to have it found—before it gets used.”

While each piece of climbing gear goes through dozens of safety checks by both the manufacturer and outside parties, ultimately it’s the end user who needs to be in charge of his own safety. Periodically check all climbing gear, no matter the age or amount of use, to take charge of your personal safety. One online commenter said it best: “Inspect all your gear before use. Use some judgment and personal accountability. And return the defects.”