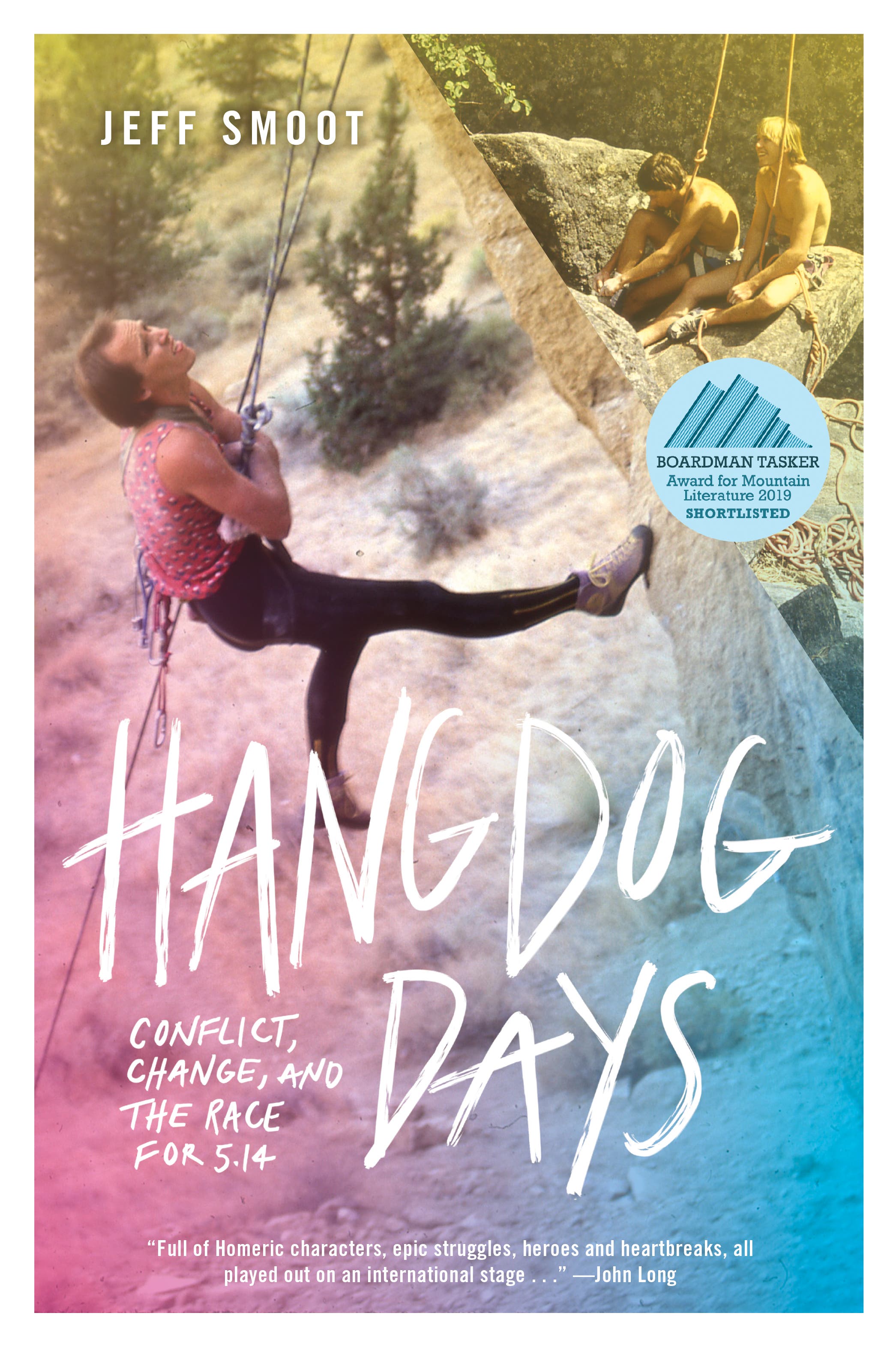

Review: Hangdog Days, Conflict, Change, and the Race for 5.14 by Jeff Smoot

"None"

Picture this: You head out for a nice day of sport climbing, wanting to clip some bolts, push yourself physically and get a little bit scared but not too scared, and be outside in a nice place with friends. But when you get to the crag, someone has taken a hammer and flattened all the hangers on your favorite warm-up, or maybe even removed the bolts altogether. So you go try another route around the corner that still has its clippers. You reach the crux but are too pumped to make the moves, so you call for a “Take” and hang on the rope. Just as you’re recovering and getting ready to go again, a couple of climbers walk by, maybe a pair of crusty, old trad-dads who kinda look like they might be bolt-choppers. They yell up, “Hangdog! Loser! Why don’t you go try a route you can actually climb instead of tearing the rock down to your level?!”

You scratch your head in puzzlement, wondering, “What the hell just happened? Have I been transported to some sort of alternate universe?”

Well, that alternate universe actually existed, and it was the American rock-climbing scene in the 1980s. Back then, sport climbing was nascent and there were raging ethical squabbles over the “proper” way to free-climb and establish new routes, with much of the friction between old- and new-school factions occurring in historical climbing centers like Yosemite Valley, Joshua Tree, and the Shawangunks where a traditional, ground-up, no pre-inspection, no-rehearsal approach had been the default. Nonetheless, despite all this drama, a handful of iconoclasts came to embrace techniques largely created in Europe like hangdog rehearsal and rappel bolting in order to push the sport’s boundaries, helping solidify the top grades of the era (5.13 and 5.14) that we now take for granted, as well as disseminating the tools and practices that made sport climbing the juggernaut it would eventually become. In other words, without this period of rapid and often-tempestuous growth, we would not be where we are today: No Red River Gorge, no Smith Rock, no Rifle, no Dawn Wall (the climb and the film), no rock gyms, no competitions, etc. Just like the 1980s saw big changes in technology—personal computers, home video-game consoles, Walkman personal stereos, etc.—that shaped the world we live in today, so too did it go with climbing.

| Climbing Book Club |

| Join us in the discussion of Hangdog Days in the Climbing Book Club Facebook group. Bonus: Group members can save 25% on everything from Mountaineers Books, which includes Hangdog Days, classics like Mountaineering: The Freedom of the Hills, and more. Join the group then check our posts to find the coupon code. |

The Seattle climber Jeff Smoot was uniquely poised to document this period, given his proximity to America’s first sport-climbing area of Smith Rock, Oregon, and his friendship and climbing partnership with the Smith sport-climbing protagonist Alan Watts and the late Todd Skinner, both primary advocates of the new tactics. In the gripping, rollicking, excellent climbing history/memoir Hangdog Days, Smoot devotes 300 pages of lively, engaging prose to this epochal period, much of it detailing his time on the road with the peripatetic Skinner—Smoot’s friendship with Skinner forms the core of the book and the lens through which we view the many bizarre ethical conflagrations.

I’m old enough to recall reading and hearing about some of these events, which are almost too strange to be true: the Index, Washington, locals who smeared grease on the 5.11 outro to City Park, to thwart Skinner’s efforts to free the 5.13d finger crack; the fistfights between friends over ethical disagreements in the Camp 4 parking lot; Skinner’s first free ascent of The Stigma, which he renamed The Renegade, on Cookie Cliff in the Valley, a line pushing 5.14 on which he fixed fins as protection and employed what today would be standard redpoint/hangdogging tactics but back then were denigrated as “sieging”—and which raised the ire of the Valley locals. Take this passage from Smoot, describing the aftermath of Skinner’s ascent:

Todd’s free ascent of The Stigma, such as it was, rattled the Valley locals’ cage. He was like a boy taunting a rattlesnake at the zoo by tapping on the glass, trying to provoke a strike. They struck fast. The pins were gone the next day. Then the rumors started, that such-and-such Yosemite climbers had been seen overzealously nailing The Stigma, unapologetically bashing in pitons and wailing them out, as if to emphasize that Todd’s ascent had been nothing more than a glorified aid climb. It was overheard that these post-free aid ascents were done with the intention of actually pinning out the crack further so the route would be easier, so The Stigma would not be—could not be—the first 5.14 in America.

Imagine that—climbers so incensed by and, more accurately, jealous over Skinner’s standard-setting ascent that they would remove his protection and even deliberately damage the rock, almost as if to erase his passage. Can you picture something like that happening today, say on the world’s hardest free climb, Adam Ondra’s Silence (5.15d) in Norway? That such a thing is unthinkable is testament to just how much we’ve evolved in the decades since—though much of this evolution came at a heavy price borne by climbers, like Skinner, who so frequently had to deal with the disbelief, aspersions, and wrath of their peers.

Hangdog Days is essential reading about this essential period, and is one of the liveliest climbing histories I’ve read—I tore through it in a week. Smoot pulls no punches in detailing the egos, characters, personalities, and conflicts of the era. Want to know how we got where we are today, where sport climbing and gyms are going gangbusters and are so universally accepted in the climbing community as to be taken for granted? Then read this book: chipping, dogging, Lycra tights, pointy shoes, and the race to establish America’s first 5.14—it’s all there, finally, in plain view and resurrected from the 1980s historical dustbin.