Ask an Editor: How Do You Test Gear?

"Kelly Corrigan" (Photo: Kelly Corrigan)

Have a question you’d like to see answered in our Ask an Editor column? Email it to letters@climbing.com and write “Ask an Editor” in the subject line.

I’ve been reading your gear reviews in print and online for years, and I’ve always wondered, how much do you really test? It seems like so many “reviews” these days are just regurgitated marketing/ad copy, but it’s hard to tell if the tester actually went out and used the gear. So what is your testing process, or how do you go about it? And how come so many items always get positive reviews? There must be some bad stuff out there.

—Terry S., via email

Years ago, or so one apocryphal story goes, an editor who was short on time to test crampons went out in front of a magazine office and walked up and down the stairs in them, to see how well they held up on “mixed terrain.” The problem was, the manufacturer wanted the crampons back after testing, so when they returned to the warehouse dulled, scuffed up, and covered in powdered cement, there was a problem. As in, “Did you guys actually test these things?”

This would be a good example of poor “real-world” testing. So if you’re picturing us doing stuff like that with the gear we review, we’ll put your mind at ease. We do actually test, yes, and there is a system and a process.

Basically, it works this way: Each year, the brands we all know and love come out with new products or refinements to existing products in their line. Usually this is broken up into two seasons. Gear for S20 would be new products for spring 2020, which usually come out in late winter on into spring, and gear for F20 is the fall 2020 gear. A lot of this centers on the Outdoor Retailer [OR] trade show, which happens in winter and summer, right before each season of new products. Companies like to debut gear at the show for the media, buyers for retail shops, etc. to consider. Our editorial staff will visit with all the relevant climbing and outdoor brands during OR, then we’ll follow up with them later, or their public-relations people will follow up with us when testing samples become available.

This is how new gear finds its way to Climbing Magazine.

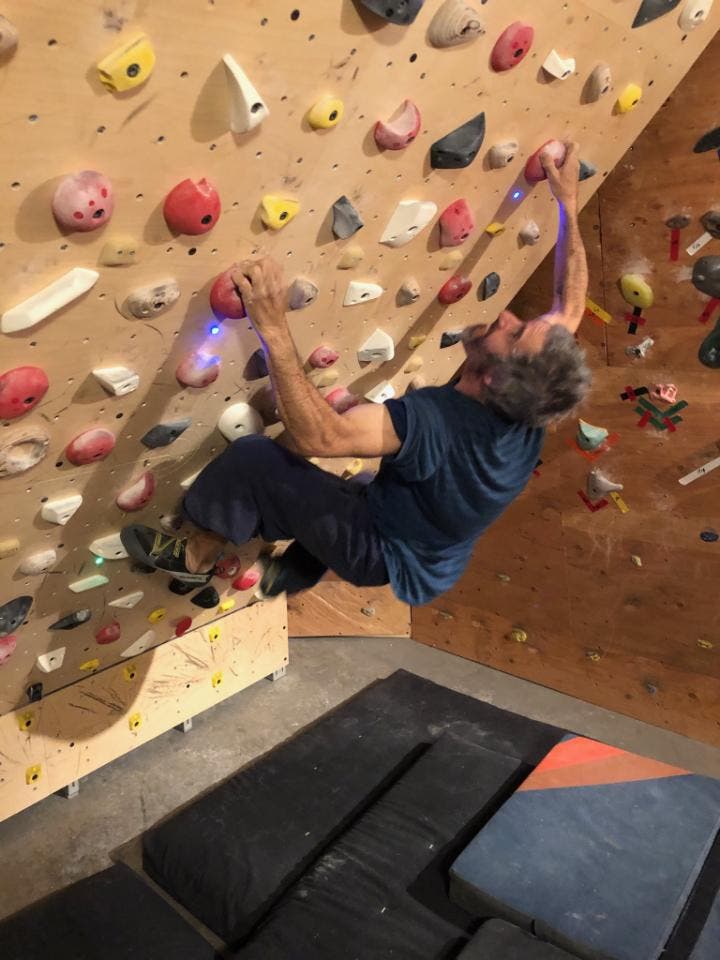

Right now, the editorial staff does a lot of the testing in-house, but we also have a roster of testers in our hometown of Boulder, Colorado, and around the country we ship gear off to. We’ll match the gear with each tester’s main discipline in order to get the most precise feedback. Typically, we’ll test an item for at least two months before we write a review, as you need dozens of days in the field to understand its full functionality, as well as to consider longevity—how well it holds up over time. Sometimes the tester will write the review, and other times the tester or multiple testers will send us feedback and we’ll compile the review. We and all of our testers do go outside and test rigorously, on multiple types of rock and in various venues in the mountains, under a variety of conditions. No walking up and down the stairs in crampons here, or wearing a pair of shoes once to the rock gym and declaiming their “new home in the redpoint quiver.”

In all cases, before we begin testing we’ll chat with the brand or PR person first about a product’s intended usage, or we might have a product sheet that lists the information. One way in which reviews, especially reviews that round up all the items in one category (like a rock-shoe or cam review), have misfired is by comparing items among brands. In a sport as specialized as climbing, this doesn’t really make sense—to say, in a shoe review, that a board-lasted shoe was much better for trad and cracks than a downturned, asymmetrical one is redundant and obvious. And it does both shoes a disservice, as both were designed with a unique, specific use in mind. Ditto for cams, ropes, outerwear, etc.—all gear has its purpose. This is what we evaluate when testing, as well as the various touted attributes of an item (“waterproof, breathable shell” or “cam slides into pin scars with ease” or “the perfect soft, downturned shoe for gym bouldering”) and how well that item lived up to its claimed attributes.

Finally, as for the fact that you see so few negative reviews—well, basically if an item is poorly made or doesn’t break new ground, and so won’t be of interest to readers, we don’t bother reviewing it. Though, in all honesty, it’s exceedingly rare to see anything of poor or unsafe quality coming from the established brands. Most of these brands have decades in the game, with very experienced product designers and strict quality-assurance protocols. It’s rare that anything shoddy slips through the gates.

There you have it—testing at Climbing in a nutshell. As for a final question that you didn’t ask—“Doesn’t the fact that you get to keep the gear mean you’re basically being bribed to write a good review?”—the answer would be no. Companies have marketing budgets that allow for sending out samples—it’s part of their process. And we don’t consider where the gear came from when it reaches us; we just consider the gear. And anyway, can you think of anyone who’d want back a rope that’s been whipped on some untold number of times or shoes that have been sweated in for two months?

Probably not!