AMERICAN MEATBALLS

"None"

Two Yanks Taste Humble Pie on the Superb Granite of Sweden

Sweden: this serene Scandinavian country conjures visions of sweeping granite, splitter cracks, and rounded blocs. Er, I mean, bikini teams, hockey, lingonberry jam . . . and more bikini teams. In short, all things not climbing. And so it is with major trepidation that, in April 2007, I board a plane to Stockholm for a climbing trip. I’m to meet my buddy Rob Pizem there, and then hook up with the local photographer Jonas Paulsson.

On the flight, I tell my Swedish seatmate I’m visiting his country to climb rocks. “Oh, you must mean hiking in the hill country,” he tells me. Then an elderly grandmother chimes in: “Are you sure the ice is in up north? It’s been warm.” The final insult comes from the flight attendant, who assures me I must be thinking of Norway, where you find the Troll Wall and other master cliffs. With no good response, I grow surly, drifting into sleep and pondering why I’ve spent nearly a thousand dollars, left my ski- and bike-rental shop in high season, and ditched my beautiful wife to climb in Sweden with bearded, smelly, red-afro-ed Rob.

The trip was Rob’s idea, spawned by a chance meeting with Jonas at Joshua Tree. In the three years Rob and I have climbed together, we’ve had some mad adventures, including the world’s longest sport climb, Logical Progression (5.13b; 28 pitches; El Gigante, Mexico). And though I’m on this plane because you never leave your wingman, this trip has even deeper meaning: it’s been a rough spell for Rob. In July 2006, he fell trying to free Arcturus (VI 5.13), on Half Dome, breaking his back; in December that year, his Austrian roommate, Hari Berger, died in a freak ice-climbing accident; and then in January 2007, Rob’s dad suffered a minor heart attack. Rob needs my support. Plus, I’m the only person who can make the trip.

Jonas lives in Stockholm and works as a part-time baggage handler. The Beta Rob gave me was simple enough: meet Jonas, who “looks like a Wookie,” at Stockholm’s Grand Central Station at 10 a.m. on Saturday. When I approach a 6’2” bearded guy with hair down his back, he says only, “My name is Jonas. We should go.” Then we’re off to the Millennium Falcon, his Audi wagon.

Sunday at 5:00 a.m., after Rob arrives, the three of us load the Falcon. Jonas is shooting a video showcasing Swedish climbing (Visit crackoholic.com) and is stoked to have two “strong” American climbers as talent. We drive west six hours, to the province of Bohuslän, passing endless evergreens and windmills, and crossing rivers, lakes, and, ultimately, fjords spreading over a flat, Minnesota-like landscape.

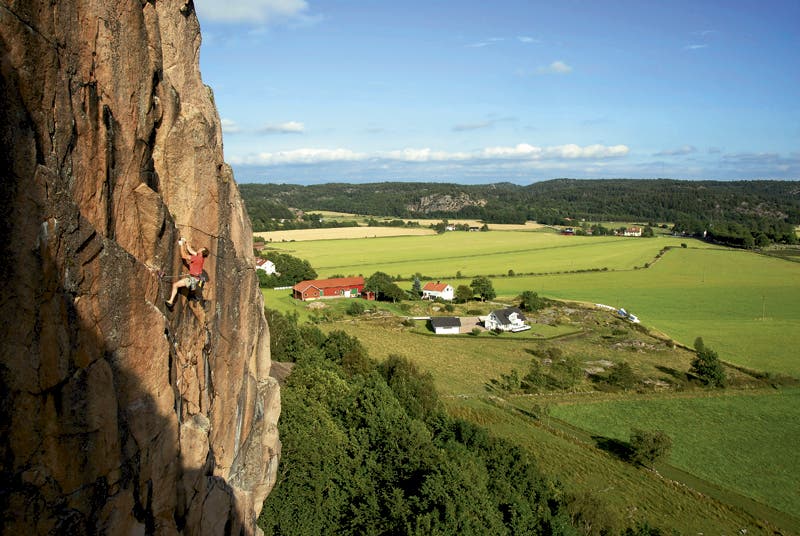

After lunch (Swedish meatballs) at a truck stop, we dock the Falcon at Hallinden, a 250-foot granite dome. The setting is a smaller-scale version of the Needles, California, or Colorado’s South Platte, with craggy domes of grey- and brown-streaked granite rising above a sea of pine. Most of the domes are about 250 feet high, with some reaching 400. They appear near-vertical and from 600 to 3,000 feet across. Crack lines abound.

They say first impressions last longest, so you want them to be good. I can promise that Swedish granite does not disappoint: it’s bullet, frictiony, and has killer cracks. Here at Bohuslän, the stone’s been scoured by eons of hard weather coming off the nearby North Atlantic. Meanwhile, the lack of traffic (the Swedish climbing association claims some 6,000 members, but how many are solely gym rats is anyone’s guess) has kept the stone free of boot polish, chalk, and human grease.

By Swedish standards (Swedish cragging dates back to the 1930s), Bohuslän is fairly young, with the earliest recorded route going up at the popular Häller in 1975. Development has since come fast and furious, and Bohuslän now boasts 1,500 climbs, from 5.5 all the way to Kärlek, an unrepeated 5.13d, at Buråsen. Hundreds of batholiths dot the landscape, sporting anywhere from five to 25 routes each.

In Bohuslän, nearly all the crags are on private land, with access generally gained by asking permission, as we do at Hallinden. The first route we try is Prisemaster, a 200-foot Swedish 6, or easy 5.10. Rob, who routinely onsights 5.12 trad, takes 20 minutes to clamber up the first 50 feet, constantly looking down and nervously telling me to “watch” him. It’s no wonder his last outing on granite resulted in that broken back, though my heckling and calling him “Gertrude” probably aren’t helping, either. After this brief period of acclimatization, we get down to business.

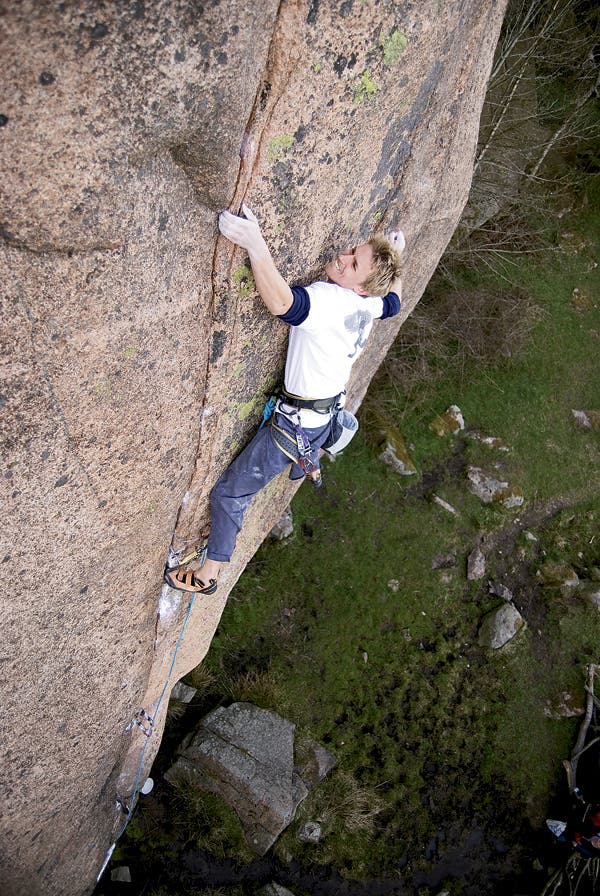

There’s a theme to Swedish trad: bold climbs, bolder climbers, and serious sandbags. The standout at Hallinden is Catch (7+, or 5.11d), a 200-foot seam up the dead-vertical northwest face. With sweet-looking fingerlocks, Catch seems like a good coda to our first day. Ten minutes and 75 feet later, Rob lowers from partway up the route.

I take a shot and soon find myself just above Rob’s high point, contemplating a thin crux of delicate crimps interspersed with laybacking on the crack’s fading lip. After fishing in four micronuts, I head up. In keeping with our “supportive” relationship, Rob is quick to offer nuggetinos of encouragement: “Looking shaky up there . . . I’ll make sure to short-rope your next clip!” or, “Just remember that I couldn’t do it, so you don’t have a prayer.” Above me, Jonas’ camera whirs away. I dig deep to fire the first half of the crux and latch a key crimp there’s only eight feet of delicate footwork to go before a rest. But I’m also insanely pumped, I can’t find any gear that fits, and I’m 20 feet out

Chewbacca, seeing me quiver, offers up some love: “Gear looks great,” he says, still firing off 10 frames per second. “This rock is bomber, and that RP is good!” Not consoled and with no pride left to salvage, I beg Jonas to lower me his static line, which I latch onto and hand-over-hand to the recovery ledge. There, I spend 10 minutes hyperventilating. I have an aftertaste of Sweden’s national food, humble pie, in my mouth. Over the next week, Rob and I will stuff ourselves silly on this savory dish.

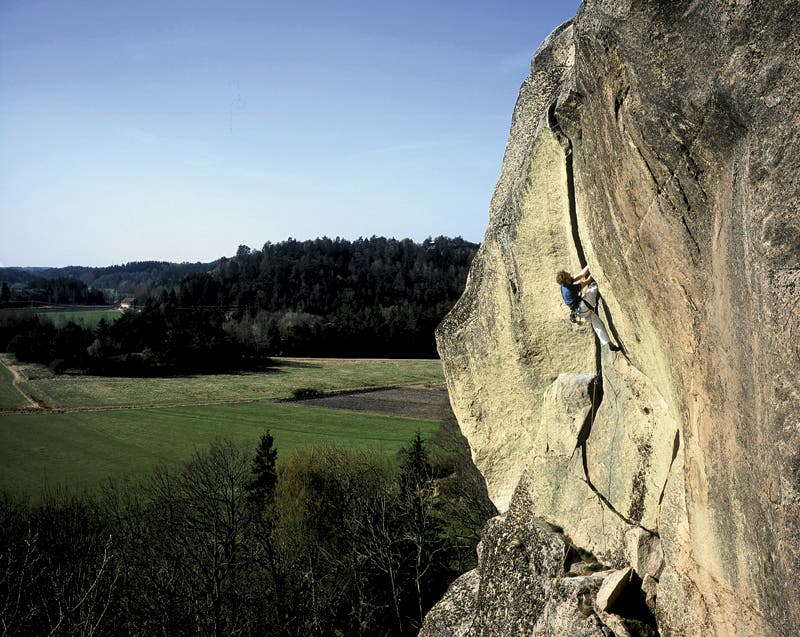

After a good sleep, Rob and I awake ready to “redeem” ourselves at Häller, a beautiful swath of granite 300 feet high and a quarter-mile long. Jonas pulls the Falcon up to a farmhouse; we step out, drop a couple Kroner ($2 donation to the landowner) in a coffee can, and come face to face with a monster: Prince, a husky draft horse who thinks he’s a lap dog. He follows us, doing his best to nuzzle into our crag packs. The highlight of the day comes when Prince successfully takes some fruit from Rob’s pants.

Jonas chooses Offline (7+, or 5.11d) as our “warm-up.” The slightly overhanging, 5-inch-to-1-foot crack is chalkless. And when Rob, 45 feet up, does a double fist stack/kick-through/inverted sit-up to a layback move 10 feet above a tipped-out No. 4 Camalot I know I’m in trouble. Significantly harder than any 5.12a offwidth either of us has seen, Offline cedes only to a one-hang effort.

At least on Tor Line (7, or 5.11a), Jonas warns us it’s “a bit of a sandbag.” Freed in 1979 by Jan Liliemark, Tor line follows a spectacular finger crack to a 10-foot roof, with perfect, hanging hand jams to a thin-hands pull over the lip. The climbing finishes with 40 feet of slammer hands and cups. It would be 5.12 in Yosemite. I blow the onsight, but Rob quickly sends, and I follow it free once I find a key foot above the lip.

Later, we watch two locals work their project. The 100-foot line on the cliff’s left side begins with a steep, bouldery section to a decent-looking handrail, allowing a traverse into a micro-thin crack system. Overhanging the entire way, the climb has little visible protection. Only psychos would conceive of leading such an unruly beast: enter the Norwegians Rein Leidal and Øystein M.K. Johnsen. Because we can’t pronounce their names, we call them Rain Man and Einstein. Einstein’s 40-foot falls repeatedly break the small wires at the project’s crux; below these, only a green Alien stands between him and a 60-foot grounder. I ask if he’s considered plugging more gear higher the crack looks to take pro. “I do not understand . . .” he answers with total conviction. “A 10-meter fall is no different than a three-meter fall both are quite safe!” My theory is that years of winter darkness have taken their toll on poor Einstein.

Ultimately, after two more days of “safe” falls, Einstein establishes Walk the Line, which checks in at 5.13b, and Rain Man follows up a few days later with the second ascent. But when the duo offers us a go on the ultra-thin, ultra-steep, ultra-unprotected open project next door, Rob and I, terrified, claim we don’t want to scoop them.

The ethic in Bohuslän is staunchly conservative. Many of the first ascentionists have climbed with British hardmen, and the influence is obvious. Leo Houlding put up a British E9, Savage Horse (a shout-out to Prince), at Häller. The climb recently received its second ascent, by Stefan Wulf, who incidentally established his own E9, Masculine, at the same crag. Jonas shows us footage of Wulf taking a 50-footer off the last move of his latest creation, Dreadline, an 80-foot E8/9. These guys like getting scared.

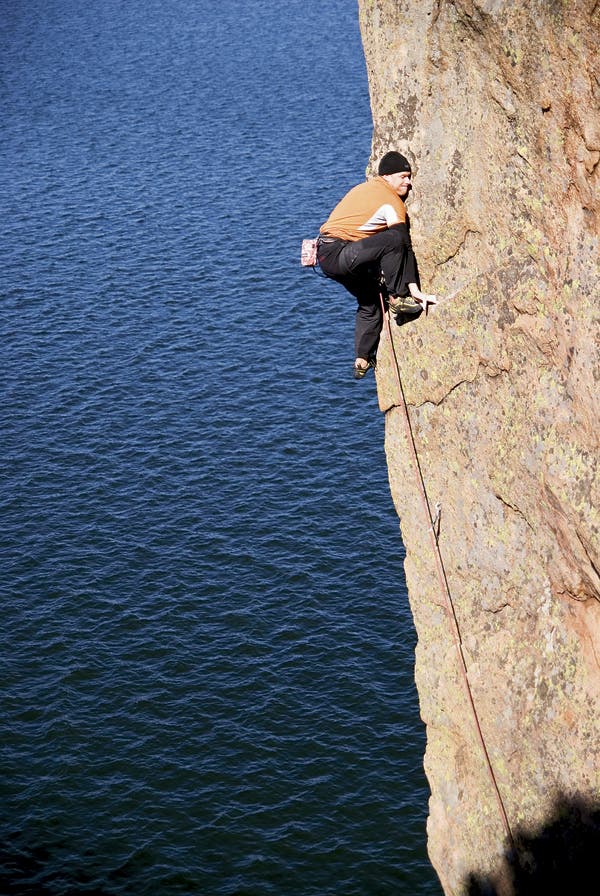

In our travels, we come across only one sport route, an unnamed line Jonas bolted at Ulorna, a mile-long-by-300-foot wall right on a fjord. He offers us a go. The position is truly magical, offering a view across the fjord and out to the ocean. We decide to call the climb Down to the Waterline 50 feet of technical crimping and devious footwork culminating with a huge move to a flake, yielding a Swedish (wink-wink) 7-, or 5.11a.

The beach at Ulorna is also home to great bouldering, with granite eggs dotting the cobbled shoreline. Other boulders are scattered throughout Bohuslän, much like around Squamish, but we’re told that, while the quality and quantity of problems is great, the perfect cracks eclipse them. We revisit Ulorna a final time two days later, and then head to a crag 10 minutes away called Galgeberget: the G-Spot.

The G-Spot is home to Masken, a laser-cut finger crack up the steel-grey heart of a 70-foot face. Masken is also the first Swedish climb I’ve walked up to and climbed in remotely decent style. However, the G-Spot is far from soft it has plenty of other ways to reduce you. On the far left side of the crag lurks the thin face and arête Aretmetik, a 50-foot 5.11+ first done in 2005 by Jans Pålsgård, impressive given the fact that 5.11d was his limit and that the “gear” is all skyhooks and slings. However, Pålsgård’s exploits seem downright rational compared to the local crew’s plan to lead the project 100 yards up the cliff. This climbs a technical slab that turns vertical and offers nothing but crystals: 60 feet and no pro.

And here’s the plan, courtesy of the local hardman Petter Restorp, who’s been toproping the route for a year-plus. First, Restorp will climb to the top of a 30-foot birch below the route and clip a line to it with a girth-hitched sling and locking biner, and then similarly rig a twin birch 15 feet away. “Protected” by this double toprope, Restorp will tackle the opening bit, his belayer poised to sprint away from the wall for a slingshot catch (assuming the trees don’t snap). When Restorp says the climb will be hard, we pay attention, as he’s just sent his longstanding project in Bohuslän, an 80-foot, gear-protected 5.13d.

The dozens of “5.10” and “5.11” offwidths at Bohuslän take sandbagging to a new level. Case in point: Presenten (“The Gift”), rated 6+, or 5.10d. This 80-foot climb, at Änghagen, was FA’ed more than 10 years ago by Magnus Strömhäll, who gave it 6+, thinking a true offwidth aficionado would find better Beta. Restorp made the only repeat, in 2006, and jokingly told Jonas he’d downgrade it to solid 6.

We borrow the required gear (three No. 6 Friends, three No. 5 Camalots, two No. 4.5 Camalots, and two No. 4 Camalots) from Restorp, who tells us in a matter-of-fact manner that “climbing Presenten feels like being beat up really bad.” He also thinks it’s harder than Belly Full of Bad Berries, the 5.13a/b overhanging offwidth at Indian Creek, but still honestly wants to know if we think it’s harder than 5.10d.

Presenten is a severely overhanging 25-foot gash that eventually eases to just past vertical . . . right as the crack widens to No. 6 Friends for another 20 feet. Or so I’m told. This route is so severe we can’t even aid the thing. Forty minutes and 15 feet later, I give up, and set to repaying Rob’s earlier insults by repeatedly reminding him, “It’s only 5.10,” as he tries to lead. We’ve soon had enough and quietly leave, minus a fair bit of skin. (Restorp, perhaps as a gesture of international goodwill, later upgrades Presenten to 5.12c.) That night, we head back to Stockholm, our egos bruised. The good news is that the climbing in Bohuslän is better than either Rob or I imagined, the crags empty, and the Swedes friendly without compare. The bad news is, we suck at rock climbing.

A month later at Devils Tower, Wyoming, I meet a Swedish couple. When they learn I’m from Colorado, they inquire nervously about the Black Canyon. Hearing they climb mostly in Bohuslän, I assure them they’ll have a great time in the Black heck, they may even find the place soft. Later, my partner asks if I’ve lost my mind, sure I’m sending our new friends to their deaths. I just smile, knowing they’ve already been well-fed on Swedish humble pie.

Mike Brumbaugh lives in Vail, Colorado where he gets his humble-pie fix at nearby Rifle Mountain Park.

Bohuslän 411

-

By Air: With planning, you can fly to Stockholm for less than $1,000. From there, rent a car.

-

By Car: Bohuslän stretches for 93 miles along Sweden’s western coast, from Gothenburg to the Norwegian border. The granite sits in the northern half of Bohuslän. From Stockholm, take the E20 to Götene, and from there, the 44 to Uddevalla and then the E6 north (toward Oslo), until you take off on 162 toward Lysekil. The 300-mile drive takes six hours, though Oslo (136 miles) and Gothenburg (93 miles) are closer.

-

Guidebooks: Klätterguide Bohuslän, compiled in 2002 by Joakim Hermasson in cooperation with the Bohuslän Climbing Club, can be bought at the outdoor shop Upplevelsebolaget, in Uddevalla, or at upplevelsebolaget.com. Jonas Paulsson also has compiled an excellent guide at highandlow.nu.

-

Season: April through September is best, with August and September offering good swimming.

-

Lodging: The Bohuslän Climbing Club offers a climbers’ hut for a nominal fee, providing clean cooking, comfortable sleeping, and a great meeting point in the Bärfendal Valley, minutes from several crags; contact Rickard Larsson (46 707 73 67 84 or ricklar@gmail.com). There is also abundant camping throughout the area, with hotels and rooms for rent in Gothenburg, or in Brastad and Lysekil.

-

Access: Most crags in Bohuslän are situated on private land, so be mindful. Park to the side of the road, keep your voice down, pack out your (and others’) trash, and stay up to date on changing access situations via klatterforbundet.se or by visiting the climbers’ hut in Bohuslän.

Swedish grade conversion scale

As the Americans Mike Brumbaugh and Rob “The Piz” Pizem discovered, matching up Swedish grades with Yosemite Decimal System grades is no simple arithmetic. An ankle-eating offwidth roof called Presenten initially received a 6+, though today it’s called an 8 (how do you say “sandbag” in Swedish?). Below, find the Swedish-to-American grade “conversions,” which, like a good slice of humble pie, should be taken with a grain of salt: 4 = 5.7 5 = 5.9 5+ = 5.9/5.10a 6- = 5.10b 6 = 5.10c 6+ = 5.10d 7- = 5.11a/b 7 = 5.11c 7+ = 5.11d 8- = 5.12a/b 8 = 5.12c 8/8+ = 5.12d 8+ = 5.13a 9- = 5.13b 9-/9 = 5.13c 9 = 5.13d 9/9+ = 5.14a 9+ = 5.14b

MB