Band of Brothers – Remembering Denali's Greatest Rescue

"None"

Morton Wood, Elton Thayer, Les Viereck, and George Argus, just about to head out on their first ascent of Denali’s South Buttress.

Four climbers stepped off the Alaska Railroad at Curry, about twenty miles north of Talkeetna, on April 17, 1954. Shouldering huge packs, the foursome crossed the frozen Susitna River, snowshoed up a tall hill, and paused to admire the view from the top. Fifty miles away, Denali sat nearly 20,000 feet above them, shimmering over frozen riverbeds and snow-covered tundra. The unclimbed, five-mile-long rampart of the South Buttress angled toward the summit. In 1954, Denali had been climbed fewer than ten times, and its south and east flanks remained completely virgin. The modern era was around the corner — ski planes had begun landing on the Kahiltna Glacier — but the peak was still very much an explorer’s proposition. It would take the 1954 party nearly two weeks just to reach basecamp, and once they started climbing the South Buttress, disintegrating icefalls and swollen rivers behind them meant they would have to complete the first traverse of North America’s highest peak just to get home. This foursome was not composed of globetrotting alpine superstars but rather a group of Alaskan friends, equipped with Army surplus clothing and tents sewn by their leader Elton Thayer’s wife, who also prepared their food in her kitchen. Thayer, age twenty-seven, worked as a ranger at Mount McKinley National Park. For the South Buttress expedition he recruited George Argus, age twenty-five, an instructor at the Army’s Arctic Indoctrination School; Les Viereck, age twenty-four, a lanky graduate student also serving in the Army; and Morton “Woody” Wood, age thirty, a veteran of the Army’s 10th Mountain Division who ran Camp Denali, a guest-cabin establishment below the mountain’s northern slopes. Thayer had made the first ascents of King Peak in the Yukon in 1952 and Mount Hess in the Alaska Range in 1951, and Wood had climbed Mont Blanc and attempted Denali from the north in 1947.

Heading across the Chulitna River’s floodplain with Denali in the distance, over 50 miles away.

Thayer’s plan was to snowshoe cross-country twenty miles to the Ruth Glacier and then continue another twenty miles up the Ruth to the Great Basin (now known as the Don Sheldon Amphitheater), where Ginny Wood, Morton’s wife, would airdrop 400 pounds of supplies.(A remarkable woman, Ginny Wood had served with the WASP air corps in World War II; she arrived in Alaska in January 1947 after she and another woman ferried a pair of war-surplus planes to the territory in a twenty-seven-day midwinter journey.) The expedition immediately fell behind schedule as the climbers slogged through heavy spring snow, battled through willow and devil’s club, and backtracked from wrong turns. Their cotton, wool, and nylon clothes were saturated with snow and sweat. After a week of struggle, they arrived at the Great Basin on April 24 and Ginny Wood dropped two loads of supplies onto the glacier. The foursome would not see another person for the next month. The team began ferrying loads ten miles up the West Fork of the Ruth to their basecamp, passing beneath the towering north face of Mount Huntington. From there, they climbed a forty-five-degree slope to a pass above the Kahiltna Glacier, then across a narrow ridge and around Peak 13,050. By May 2, after two and a half weeks of effort, they finally reached the base of Denali’s South Buttress.

Morton’s wife Ginny flying over the Ruth Glacier, preparing to drop supplies for the team.

Thayer carried Bradford Washburn’s aerial photos of the proposed route, and based on those pictures he expected mostly soft snow and easy step kicking on the South Buttress. But the climbers instead found continuous hard ice on the 1000-foot-high, forty-five to fifty-five-degree slope above their second camp. Today, this face would be a moderate day’s climb, but the 1954 foursome didn’t know how to ascend steep ice on the frontpoints of their crampons. Instead, the leader leaned over and hewed steps in the ice with his long axe, while the others carefully balanced up these steps beneath him. Each step might require five to ten minutes of chopping, and the effort was exhausting. Ice chipped by the leader bombarded the lower climbers. The team carried 12 ice pitons for belays, but these were unlikely to stop a fall on their quarter-inch manila ropes. One day they only progressed 100 feet. A few team members had recently seen a film of the 1953 Everest first ascent, in which expedition leader Sir John Hunt intones at one point, “Our problem today is to get four tons of equipment up Lhotse Face.” Now confronted with a similar big ice face on Denali, Thayer turned in mock seriousness to his partners and affected a British accent: “Our problem today is to get these bloody packs up Lotsa Face.”

The team recovering the airdropped supplies.

At midday on May 5, the third day of work on Lotsa Face, a storm forced the climbers to retreat just below the top of the face. Four days later, they dug out their steps and finally reached the crest, catching sight of Denali’s summit for the first time in a week. On his way back down to pick up a load, Wood counted 1038 steps hacked in the hard ice of Lotsa Face. Above, more steep ice appeared to block their route, but the team discovered a tunnel leading underneath an enormous ice cornice that cantilevered sixty to eighty feet over the Kahiltna Glacier. The astonished climbers walked and crawled under the ice roof, pushing their packs ahead of them as they wriggled through tight blue caves. At the far side of this remarkable passage, they found easier ground.

Elton Thayer, punching through a large cornice just before the team started up the South Buttress.

With excellent weather continuing, they decided to save time by no longer leapfrogging loads. Instead, they hefted packs weighing up to ninety pounds and headed upward. As they climbed over the 15,885-foot high point of the buttress, they were awed by views of Denali’s 8000-foot south face next door. On May 12, they placed their fifth camp at the edge of the Great Traleika Cirque, a huge basin below Denali’s upper east face. From there they would descend about 1500 feet and then climb back up the other side to reach a 17,200-foot pass, the door to the Harper and Muldrow glaciers and the well-known route home. As Wood looked over the pass, he felt a surge of relief — not because of the proximity of the summit but rather because of the certainty that he and his friends wouldn’t have to retreat down the long route they had just climbed.

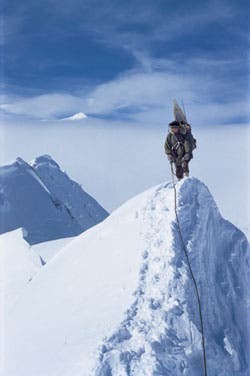

Morton Wood, an island in the sky on Denali.

Acclimatized by nearly a week above 15,000 feet, the four men hiked easily to the top of North America on May 15. They left their names and the date on a slip of paper in a tin can and were back at high camp by 4:30 p.m, tired but happy. Thayer’s dream of a new route on Denali had been fulfilled, and they expected to reach civilization in just four days. Throughout the difficult climb, the team’s camaraderie had never wavered. “Not often can four people live together so intimately under such trying conditions without ever experiencing the slightest frictions or personality conflict,” Wood wrote in the American Alpine Journal afterward. Reflecting on the events that befell them the next day, he could not fault their decisions. Snow conditions along their descent route were poor, but returning down the South Buttress was unthinkable. Perhaps they were feeling rushed. It was the last day of Argus and Viereck’s thirty-day leave from their Army posts, and they would soon be AWOL. Perhaps they were overconfident because they were on their way down and Wood had climbed their proposed descent route seven years before.

Thayer cutting steps high on Lotsa Face.

The descent went smoothly at first. They zigzagged down the Harper Glacier and onto Karstens Ridge, and by the end of the day they were below 13,000 feet. With about a foot of loose snow over hard ice, the footing was treacherous and they moved carefully as they neared their intended campsite. Three climbers belayed each time the fourth moved, but solid anchors were nearly impossible to find. Two of the men’s ice axes were cracked from general wear and bound together with tape. As the ridge steepened at an area called the Coxcomb, they descended below the crest on the northwest side. Thayer was last on the rope. The others were watching as their leader stumbled and began to slide; he was wearing soft mukluks and his crampons may have shifted on his feet. Instantly, they all leaned on their axes, pushing the dull spikes into the ice, but as the rope came taut each man was plucked from his precarious stance and all four cartwheeled down the steep slope, bouncing off ice blocks and pitching over short serac walls. “It was like [taking] a bad spill while skiing in powder snow except that it seemed to last for an eternity,” Wood recalled in the AAJ. “I remember once falling free in the air for at least a second or two and then landing on my pack in deep snow … More sliding, rolling, and another long free fall — then suddenly silence except for the gentle hiss of the snow that was still in motion all around me.” Argus was jerked away from the wall, his feet kicking in the air. He tried to shed his pack as he fell, hoping to avoid breaking his arms in the straps. He had one arm free when he slammed into an ice block and blacked out. Wood could not believe he was unharmed when he came to a halt. They had fallen at least 800 feet and come to a stop only when Viereck wedged in a crevasse and the rope halted the rest of them. They were strewn across the steep slope only a few yards above a 400-foot cliff, just to one side of the massive Harper Icefall. Wood saw Argus sitting below him, then looked up and saw Thayer dangling off a fifteen-foot-high serac from the rope tied around his waist. Wood desperately struggled to untie the knot around his chest and then stood up. Viereck had extracted himself from the crevasse and was standing forty feet above him. The two men quickly established an ice-axe belay, lowered Thayer from the serac, and rushed to help him. But it was too late. He had broken his back in the fall, probably when he slammed to a stop in mid-air.

Argus and Wood descending Karstens Ridge just moments before the accident.

Argus was badly injured. Most of his front teeth were gone and his right hip was dislocated. Ligaments and tendons in both legs were torn. He could hear Wood and Viereck talking, and then Wood was by his side. “Where’s Elton?” Argus asked his friend. “He’s dead,” Wood said. Gently as he could, Wood moved Argus onto an air mattress and slid him to a level spot where they could pitch their three-man tent. Gear was strewn everywhere, and Wood and Viereck — who seemed dazed and complained of pain in his chest — climbed slowly up and down the slope to recover what equipment they could. Wood gave Argus some codeine tablets for his pain, and then, while Argus dozed, Wood and Viereck buried Thayer. Finally they all moved into the tent and cooked a meal on their battered stove. The three men spent six nights in the camp, hoping Argus would improve enough to move down the mountain. Each day, Argus was a bit stronger, but his teammates soon realized that walking — even crawling — was out of the question. Wood and Viereck stamped SOS messages in the snow, hoping Ginny Wood might fly past in search of them. But the clock was ticking. Nearly every day a little snow fell, and the climbers knew a big storm might erase them from the exposed avalanche slope. Finally, they decided to move. On May 22, Wood and Viereck began kicking a path in the snow toward the flat glacier about 1000 feet below them. They wondered how they’d ever get their friend down one seemingly impassible stretch of icy steps and crevasses, but they had little choice. “We got ourselves into this mess, and it’s up to us to find a way out of it,” thought Wood. They wrapped Argus in the tent, put him on top of two air mattresses, padded him with their extra clothes, knotted loops of rope around him, and tied their climbing rope to the loops. Before they left, Wood marked Thayer’s grave by nailing the wreckage of his packboard to the serac where Thayer had fallen. Then, with one man pulling the litter and the other behind to steady the ropes, they began sledging Argus down the snowy trough they had dug, carefully lowering him over ice steps and along the lips of crevasses. After sixteen hours of work, with a sense of enormous relief, they reached the Muldrow Glacier, out of range of the looming seracs. They dragged Argus to the middle of the glacier and pitched their tent. The next morning at six a.m. they heard a plane flying overhead. Wood leapt out of the tent with the remains of his broken signaling mirror. Ginny Wood flew overhead just as her husband reached some sunlight and flashed a reflection onto the plane. But his wife didn’t see the signal — she was intent on searching the south side of the peak, and fresh snow had buried their tracks. “George,” Wood said to Argus. “We’re out of options. Les and I have got to go get help.” The two uninjured men placed most of their food and their single remaining quart of fuel within easy reach of their friend. They sliced open an empty one-gallon gas can to use as a bedpan. They figured Argus could make the fuel last a week. Wood and Viereck took only a little oatmeal, some chocolate bars, and five small pieces of energy-packed Logan bread. They faced a trek of roughly thirty miles to the road at Wonder Lake. Before they left, around noon on May 23, Argus asked the two men to send a wire to his mother saying that they had made the summit and that “everything was fine.” The Muldrow was heavily crevassed, and the two men felt horribly exposed as they snowshoed through the maze of slots. If either man fell into a crevasse, the other might not be able to pull him out and both they and their friend Argus might die as a result. Wood remembers the mountain looming behind them as “a physical force that drove us to keep going.” With skilled route finding, aided by Wood’s previous trip up the mountain, they made it to McGonagall Pass, the exit from the Muldrow Glacier, by 3:30 a.m., after fifteen hard hours of tense walking. They expected to find food cached at the pass by previous expeditions, but nothing was there. They dozed for four hours, ate one Logan biscuit apiece, and then began hiking down Cache Creek toward the road. They walked all that day and through the next night, crossing twenty miles of tundra, and forded the McKinley River at 4:30 a.m. on May 25 to reach a cabin that Thayer, following an old Alaskan tradition, had stocked with food the year before. Wood and Viereck cooked breakfast and slept another two hours. Then they began walking toward the road at Wonder Lake. As they crested the last hill, the two were stunned to see no tracks on the road. It was still closed by the winter snows. They had been marching for two days straight, and now they faced an ordeal they of which they hadn’t dreamed — another eighty-six miles of walking to reach the open road. It would be at least four more days before they could start a rescue for their injured partner. How much longer could Argus hold out? At that moment, George Argus may have been the most isolated human being in North America. With the road to Wonder Lake still closed, he lay at least fifty miles and 10,000 vertical feet from the nearest car as the crow flies. No one was attempting the Muldrow Glacier route that season. Argus’ fate lay completely with his two friends. Two days before, as Wood and Viereck walked away from his tent, Argus listened to the scuffle of their steps fade and felt his spirits sink. “Woody!” he yelled out of the tent that afternoon, forgetting that his friend had already gone. “Woody!” His voice was swallowed up in the vast stillness of the glacial basin. Argus had some morphine, but the pain in his legs didn’t seem too bad and he didn’t want to risk a drug-induced stupor, so he limited himself to an occasional codeine tablet. He knew he had to keep eating despite the pain in his five remaining front teeth, which had been smashed backward in the fall. He ate two small meals a day, killing time with the careful preparation of his oatmeal and powdered egg. He melted a bit of chocolate in his powdered milk each night, hoping the treat would help him sleep. As the days dragged on, Argus wondered if he could fashion some sort of crutch in case his friends didn’t return. He briefly tried crawling, but the pain in his hip was too great. Unable to move outside the tent, he spent hours reading a book of Mark Twain short stories, lingering over each page.. Clamorous ice avalanches pounded the walls above him. He couldn’t see them because the opening in his tent pointed down the glacier, but he could feel powder snow drift over the tent after a big avalanche. Falling snow gradually collapsed the foot of his tent and began to soak his sleeping bag. On the night of May 25, he struggled to stay awake and wiggle his wet toes to keep them warm. He spent much of the following day in an exhausting and painful struggle to change his boots and socks, replacing them with Inuit mukluks that had sealskin uppers and walrus-skin bottoms. His toes had some minor frostbite, but for the moment they were out of serious danger. That morning, Argus heard planes fly overhead several times, and his hopes rose. He felt sure his friends must have reached the road and that a rescue was on its way. Wearily, Wood and Viereck left Wonder Lake and started hiking again. Their feet and bodies ached — they had hiked and climbed some 130 miles since leaving the Alaska Railroad nearly forty days earlier. They had one more chance to avoid walking all the way to the open road. A solitary old prospector lived at Kantishna, about five miles away, and he had a radio. When they reached the Kantishna cabin, Wood quickly asked the miner, “Can we use your radio?” “Nope,” the man said. “Batteries are dead.”

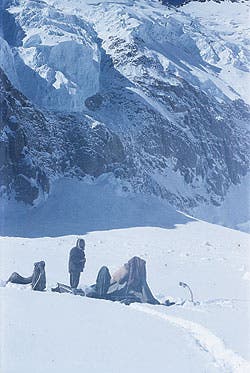

The makeshift Muldrow Glacier camp where George Argus spent six days in solitary confinement before being rescued.

As the two dejected climbers tried to rally their strength to walk another eighty miles, they suddenly heard voices outside. Bursting out of the door of the cabin, they saw two men hallooing to them across a river; the men, park rangers, had shoveled through drift after drift to open the road for the season. The climbers piled into the rangers’ Dodge Power Wagon, and by 10:30 p.m. they were at the park headquarters. That night, an eight-man rescue team was organized, led by Dr. John McCall, a geology professor at the University of Alaska who had climbed Denali six years earlier. A rescue was under way, but Argus was not yet out of danger. These days, given a bit of fair weather, a helicopter rescue at 11,000 feet on the Muldrow would be a snap; helicopters have picked up climbers above 19,000 feet on Denali. But in 1954 such rescues had not yet been attempted on the mountain. The Army’s Sikorsky H-5 “Dragonfly” helicopter (famed for behind-the-lines rescues in the Korean War) had a rated ceiling of about 10,000 feet. On May 26, the rescue team choppered to about 5500 feet on the Muldrow. They would have to travel about fifteen miles up the glacier to reach Argus’s 11,000-foot camp and somehow, if he was still alive, transport the injured man back down to the landing site. Planes dropped supplies and an aluminum sled for carrying Argus. Two feet of new snow slowed the rescuers’ progress, however, and buried some of the airdropped supplies. The rescue effort prompted dire headlines in the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner: “Snow falling; Searchers Losing Trail to Climber; Thermometer Drops to 10 Above Zero at Level Where Helpless Man Awaits Rescuers; Situation Getting Critical.” By radio, the team requested that Wood return to the mountain to help find the way, but he couldn’t join them, as the helicopter could not fly in the snowstorm. Rescuers spotted Argus’ tent from the air but saw no sign of movement. Nevertheless, they remained hopeful because Argus appeared to have knocked fresh snow off the tent walls. From his lonely bed on the glacier, Argus heard the planes overhead and knew a rescue must be getting closer, but he fretted impatiently as the days passed. The rescuers needed five days to find a safe trail up the Muldrow. Late in the afternoon of May 30, one week after Wood and Viereck left him, Argus thought he heard voices outside his snowbound tent. He shouted but heard no reply. After a long moment, he heard voices again and struggled to heave his shoulders and head outside the tent. A figure approached and yelled, “Are you OK?” “Sure I am,” Argus replied, and offered to fix his rescuers a cup of tea. Alone for seven nights, Argus had conserved his food and his single quart of fuel so well that he had supplies for at least four more days. The rescuers found his remaining food arranged in neat rows, with daily rations where he could easily reach them. His tent reeked. He had been in the same clothes for six weeks and hadn’t been out of his sleeping bag in a week. “When we looked into the tent, we gritted our teeth,” McCall later told reporters. To the rescuers, Argus seemed in fine spirits, and McCall remarked, “No normal man could have gone through what he did. He’s a very exceptional person.” For his part, Argus says fifty years later, “I think a lot of ‘normal’ people could have done what I did — it’s just that few of us are tested.”

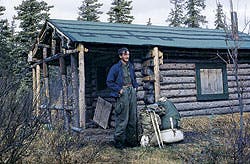

Les Viereck at Thayer’s provision-stocked cabin which was Viereck and Wood’s final stop before regaining civilization and instigating the rescue party for Argus.

The ordeal wasn’t quite over. The exhausted rescuers, fueled by airdropped benzedrine tablets, dragged Argus in the sled down the trail they had marked through the Muldrow’s crevasse fields. Argus, a budding naturalist, insisted they bring along a few sacks of rocks he had collected from the mountain. After a thirty-five-hour push, they reached the landing site, where, after 44 days on the mountain, the last member of the South Buttress team was airlifted to safety. As he flew toward the hospital aboard a series of transport planes, Argus kept mumbling, “Oh, it’s good to get off that mountain.” At a hospital in Anchorage, surgeons went to work on his damaged jaw, dislocated hip and severed patellar tendon. Wood wrote in the AAJ, “I would never encourage anyone to climb the mountain by [the South Buttress], as it is not, in my opinion, either safe or practical.” But, as Andy Selters writes in the new Ways to the Sky history of North American mountaineering, “Since then, advances in snow and ice climbing, and especially the ski-plane option of beginning and ending this route at the Kahiltna Glacier, have made this arguably the finest moderate route to the top of the continent. “These companions had enjoyed a tremendous adventure far from the eye of civilization,” Selters concludes. “But the loss of their friend Thayer eclipsed their gusto for the first traverse of Denali and one of the greatest expeditions of the decade, and the three survivors never did another major climb.” After months in a cast, George Argus recovered from his injuries, earned a Ph.D. from Harvard, and is now researcher emeritus of the Canadian Museum of Nature. Though his knees give him some trouble, he still enjoys folk dancing. Woody Wood and his wife, Ginny, established Camp Denali near Wonder Lake in the early 1950s; they later divorced and Woody moved to Seattle, where he worked as a high school language teacher until retirement. Les Viereck, also retired, was a forest-ecology researcher affiliated with the Institute of Northern Forestry and the University of Alaska; he earned fame during the Cold War for risking his career to help derail a federal proposal called Project Chariot, which aimed to blast new harbors in the Alaskan coastline with nuclear bombs. In June of this year, Wood, Argus, Viereck, Ginny Wood, and Bernice Thayer, Elton’s wife, met at Camp Denali to mark the 50th anniversary of the South Buttress expedition and to remember Elton Thayer. Thayer was memorialized on the mountain he loved with the renaming of Great Traleika Cirque, the huge bowl on the east side of Denali where he and his friends camped just before they reached the summit, assuming all their troubles soon would be over. High and remote, Thayer Basin greets the dawn with a splendor few people ever witness.Dougald MacDonald, author of Longs Peak: The Story of Colorado’s Favorite Fourteener, has twice climbed to 19,500 feet on Denali, but not reached the summit.