Black Hole

"None"

A Paranoid Trip into Arizona’s Uncharted Bouldering

“I’m gonna slit your throat open…” says the deeply distorted basso on my voicemail, one week before a mag-sponsored bouldering trip to Flagstaff, Arizona.“You better think twice about bringing Climbing down here. That’s right… close your blinds… turn off your lights… but I still have you in my crosshairs.” The message ends. I had heard about the notoriously xenophobic Flagstaff locals, so I’m not too shocked. None would return my phone calls while I dug around for info on the area, prior to my fall 2006 visit. Hell, I’d even read their nonsense on the Net. As one message-board pundit wrote: “dear klmbng… fuk [sic] you. why don’t you write a piece about some other place that courts you [sic] kind of over hyped [sic], promotional bullshit.” Then the phone rings. I pick up and hear someone breathing heavily on the other end. I pause a beat, worried, and then the caller cracks up. “Yo, dawg, it’s me,” says my friend Nelson Carayannis, a scruffy Greek kid who spent the last two years living out of his Toyota pickup. “Did I scare you?” He laughs more. “Sorry. …”

This small city of about 55,000 residents, home to the usual Southwest ethnic blend and roughly 20K Northern Arizona University students, is nestled in the geothermal war zone of the San Francisco volcanic field, a mere 60 miles from the Grand Canyon in a beeline. The region includes more than 600 volcanoes, which have disgorged a veritable bonanza of basalt and the granite-like dacite. Underneath all the volcanic rock prevail its sedimentary cousins, Kaibab limestone and Coconino sandstone. With such a rock smorgasbord, it follows that the climbing must vary, too. Angles range from Flagstaff’s flagship — the horizontal limestone roofs of Priest Draw — to the slabby-to-overhanging sandstone cliffbands, vertical, granite-like eggs, chunky basalt, and gently-past-vertical limestone in other areas. Flag houses scores of rock, all secret or semi-secret, but we won’t have time to see everything. We meet in Colorado Springs and drive Climbing’s obnoxious company vehicle, the “Spray,” south and west. (This air-brushed, poseur wagon can barely drive 20 miles, much less the 2,500 we’re planning. Unfortunately, it’s the only car big enough for us and our five crashpads.) Jody’s the odd woman out. A sarcastic chemistry major at the University of Colorado-Boulder, Jody had recently made the second female ascent of Bush Pilot (V11), in Rocky Mountain National Park, her third V11 of that summer. Eric Scully and Nelson — both Rifle “locals” who remind me more of skateboarders than climbers for their flippant attitudes — join us. Scully climbed 5.14 at 13 years old, and he still crushes (10 years later); Nelson serves as comic relief, but his moves are strong. We have local resources during the trip, thankfully — three nice locals: my friend Jeremiah; his wife, Jenn; and their 2-year-old harlequin Great Dane, Abe, who tries to fit my face into his mouth by way of introduction. We’re crashing at their place. They (and a couple of their friends) will help us navigate Flagstaff’s back roads, raining down helpful Beta (and, afterward, likely fielding the fallout from our visit). Heck, even after Nelson boots a partially digested Arby’s roast beef sandwich into Jeremiah’s toilet our first night in town, they don’t throw us out. Later that evening, Jeremiah tells us all about epic limestone swells and roofs in a shallow canyon just down the highway, called Priest Draw. As we’ll learn, the problems at Priest Draw are quality, but the area is micro. There’s essentially one style: “thug roof.” And there’s a limited number of roofs on which to thug.

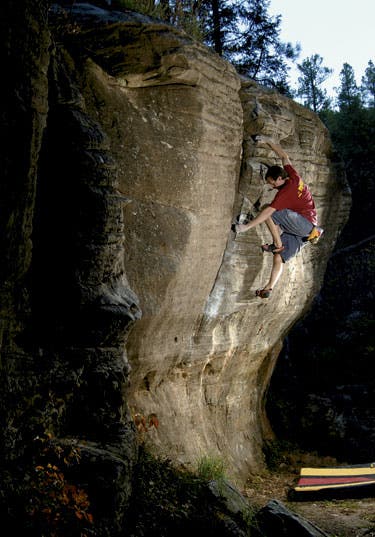

In Sharma’s Rampage, Wifebeater looks bad-ass. Cool slopers with little crawslies lead to a wild mantle. Scully does it campus in a few burns, utilizing none of our accrued Beta. The rest of us gangbang the line until a bearded Unabomber-looking local approaches. “Here we go,” somebody whispers, fearing a bugged-out tirade; our man’s surely seen the Spray, parked at the back entrance. Has he slashed the tires yet? I scan the hillsides, looking for a sniper. “Use the heel/toe… that’s the Beta,” he says, before getting on the line. He nearly “flashes” it (again) and then disappears. We give his Beta a shot, and then we continue, with reckless abandon, using our own. At day’s end, we walk back to the Spray through tall, dry buffalo grass, a quickly setting sun lighting our sore, red hands. Now, we rest. Tomorrow, it’s Gloria’s, a mountain-sized cluster of Hueco-stacked dacite blobs on the edge of town. John Sherman used Gloria’s Flyswatter as a benchmark comparison for V8s in Hueco — for calibrating his Vermin scale. Another Hueco legend, Bob Murray, also developed here. On Jeremiah’s advice, we start in the Heart Cave and get familiar with dacite’s slick, bomber composition — a result of its slow emergence from Mount Elden, the dormant volcano on the northern edge of town. Among the Ponderosa and oak trees at the base of Elden, I bump into a friendly local who boulders with me up several pitches’ worth of slabs. Scrambling around, I notice that many of the larger blocs at the base extend up to 25-plus feet, and the landings often suck. Some could use bolts. Jeremiah tells me many have likely been toproped but not bouldered. None of us are eager to be the first — Gloria’s futuristic highballing is better left to the likes of Charles Fryberger or Jason Kehl. Instead, I tell Keith about the slab bouldering, with its softer landings and intermediate difficulty. He stops shooting immediately and shoes up. Keith loves slab climbing. He returns, equally as delighted, 15 minutes later. Gloria’s is a paradoxical blend of nature and city. As at Hueco, it seems the non-climbing local slime come here to get piss drunk and spray paint profundities (e.g., “BILL-P WAS HERE”) on the rock, and the sounds of squirrels might be interrupted by the giggles of teenagers, bunched under an overhang, burning bowls. It’s all part of the experience, though. We end the day at sunset again, walking 10 minutes to the Spray, ready for ice, hand salve, cold beer, and friendlier stone.

Kelly’s can get sandy — like any sandstone area. However, the variety in angles and the friendliness of the holds more than make up for it. And like most areas in Flagstaff, you won’t hear names or grades; their absence only enhances the pure pleasure of grabbing comfortable grips, 10 feet above riverbed cobbles in a quiet forest. Nelson and I explore, wondering if each new problem will measure up to the last. We try lines well into darkness, climbing by headlamp, as animals, insects, and maybe even gun-toting locals move around us in the enveloping woods. Maybe. In the spirit of exploration and full Flagstaff immersion, we venture into Buffalo Park to sample the gritty, quick-fix basalt the next day. It’s, well, OK. As with most of Flagstaff, Buffalo Park offers cliffbands, but on average there are too many holds to milk a lot of true lines from this small area. The local Tony Disanto and I huck ourselves at a challenging dyno to a slopey ledge, and then hop into a corner to try an overhanging V10. The rock probably wouldn’t be too bad, but because this is our fourth day on, our skin groans. We pull out for the day, more psyched for sushi and sake than climbing. That night, while waiting for a table, we overhear a local climber explaining to his girlfriend (with proper embellishment) why she won’t see a photo of him in Climbing: “I climb 5.13, and I would be in the magazine, but it’s all about who you know,” he brags. (He’d likely seen the Spray parked across the street and noticed our chalky hands.) Nelson and Jenn squirm with delight, but I anxiously wonder if the guy isn’t passive-aggressively telling us to get the hell out of Dodge. My stomach churns. I imagine a brawl erupting here and now: a ninja tosses sake into someone’s eyes, a Ginsu knife fight set to Japanese techno music, choreographed dancing, shrimp tempura embedded in open wounds… I later approach the loudmouth and ask if he’d like join us the following day, to let him know it’s not about who you know. He’s not a climber, he says. His girlfriend looks shocked by his answer. Whatever. I return to wasabi-soaked raw tuna and warm sake, anticipating the following day’s visit to Flagstaff’s crown jewel, Cherry Canyon.

Cherry Canyon is an under-developed limestone bouldering crag with tremendous potential. Rumors of a mountain lion patrolling this zone — stalking boulderers — circulated during our visit, with one local telling me this same cat chased a climber to his car a month earlier. (Great: first locals, now mountain lions.) I convince myself that he says this to scare us, but after discovering a rotting elk carcass under one of the area’s most difficult problems, I give the tale more credence. It’s a pirate’s sanctuary in Cherry Canyon: you drive for almost an hour down red-dirt back roads before stopping at an almost arbitrary, torn-down fire circle. Then you walk “that direction,” as one local says, down steep, random gullies and around thick, overturned trees and high-desert scrub. Cherry breaks down naturally into small sectors, separated by five-minute walks in dried-up river beds and grassy ravines. No trails. No guidebook. You’ll only hear a soft wind through the Ponderosa, and that’s why locals love it. This canyon might host the most difficult stretch of climbing in Arizona. Chris Sharma snuck back to Flagstaff specifically to knock out first ascents here, and such other strong-johns as Sam Davis left their mark, as well. The climbing is slightly past vertical, on crimps and small pockets, and it’s very fingery. Monsoon rains (mid- to late-summer) can leave some of the spots flooded — go figure — with mud pools forming underneath and holds dirtied by runoff. But mini-cliffs above the basement floor offer an everdry playground. We end the day, after five exhausting hours of climbing and playing with tarantulas, by hiking up steep, rock-strewn hillsides, rain soaking our pads as lightning touches down in the distance.

The team and the Spray-mobile.Photos by Kieth Ladzinski

We had five days to tour Flagstaff. We slept on dusty floors and drank way too much coffee. Nelson got food poisoning. The dog shat on the passenger seat (twice). We bought truckstop T-shirts with animals on them. We broke down and abandoned the Spray on the way back through New Mexico. We took photos. We had fun, and all without any in-your-face local enmity. My misgivings, it turns out, had all been a case of ridiculous paranoia, fueled by Nelson’s silly voicemail. And somewhere in all this, we climbed. We climbed in the heat. We climbed in the dark. We climbed in the rain. We tore skin up. We did it all, and we chose Flagstaff. No guides. No grades. No names. Good rock. It’s a testament to the idea of climbing purely for the movement, the line, and nothing else. Now I know why the locals don’t want to talk about it.

Senior Editor Dan Dewell harbors a fear of many things, including snakes, the Ebola virus, and commitment.