Climbing Magazine Print Preview: August/September 2018 Photo Annual

"None"

Editor’s Note

Confessions of a Poseur

In 1990, I shakily crimped my way up the micro-pockets on Touch Monkey (5.13a) at Cochiti Mesa, New Mexico. My climbing partner Randall Jett and I had cobbled together a guidebook for northern New Mexico and needed cover imagery, which the Albuquerque photographer Dave Benyak would snap. As Dave shot from the rim behind me, I led up in a tight pair of Asolo Runouts, a novice redpointer on my hardest lead yet. I made it to the crux, and with strength to spare just needed to make one last snatch. Instead, I yelled “Tension!”; I was scared of falling, of failing, of something. Still, Dave clicked away.

“That was great, Matt!” he said while I dangled there, feeling like the world’s biggest loser. “I think we nailed it.”

We nailed it? Really? But I’d punted!

Before that day, I had little idea how climbing photography worked. I supposed it involved hanging over the cliff edge on a rope with a camera, but I didn’t know much beyond that. Also, I was sure that the climbers pictured had to have done the climb. I mean, with something like skateboarding, you couldn’t pretend to do a McTwist for the camera—you just had to do it. So why should climbing be any different?

When Dave shouted at me, I suddenly got it—it didn’t matter whether I climbed the route. Just that it looked like I had. The image would thenceforth have a life of its own based on its artistic merits, while it was up to me whether I returned to redpoint Touch Monkey.

Which leads to a dilemma: Is it ethical to pose or shoot climbers on routes they have not yet completed? Originally, climbers shot themselves in the moment, climbing a wall or mountain. But then technology improved, cameras got lighter, gear companies needed better photos, and pros needed slideshow images. The demand for polished climbing imagery created the métier of climbing photographer. Along with this came posing—often the quickest way to create a dynamic, well-composed shot. Compare an iPhone butt shot of your buddy Rufus Roughneck thrashing on Locals Only Roof to the images on these pages, and you’ll see what I mean.

As magazine editors, it’s our job to publish high-quality, evocative photos. And so, yes, that sometimes means using posed images: re-creations of redpoints, climbers on routes at odd times of the day (the golden hour), and so on. Still, we’re selective—the best photos are those that look the most natural, even if they have been posed. And when a shot goes overboard (dramatic chalking, the exaggerated shakeout, hammy facial expressions), it’s usually pretty obvious.

Which leads me back to my first-ever posedown, on Touch Monkey. I still haven’t returned to send. However, since then I’ve completed most of the handful of routes I was shot on—maybe not that exact time, but later. Still, you’d never know from the photos; you’d have to ask me, and I’d have to tell you. Such is both the art and artifice of climbing photography, a moral dilemma as old as the lens itself.

—Matt Samet, Editor

Get Climbing Magazine:

In this issue…

Features

You Meant to Come Home

The lives and climbs of Hayden Kennedy, Scott Adamson, and Kyle Dempster.

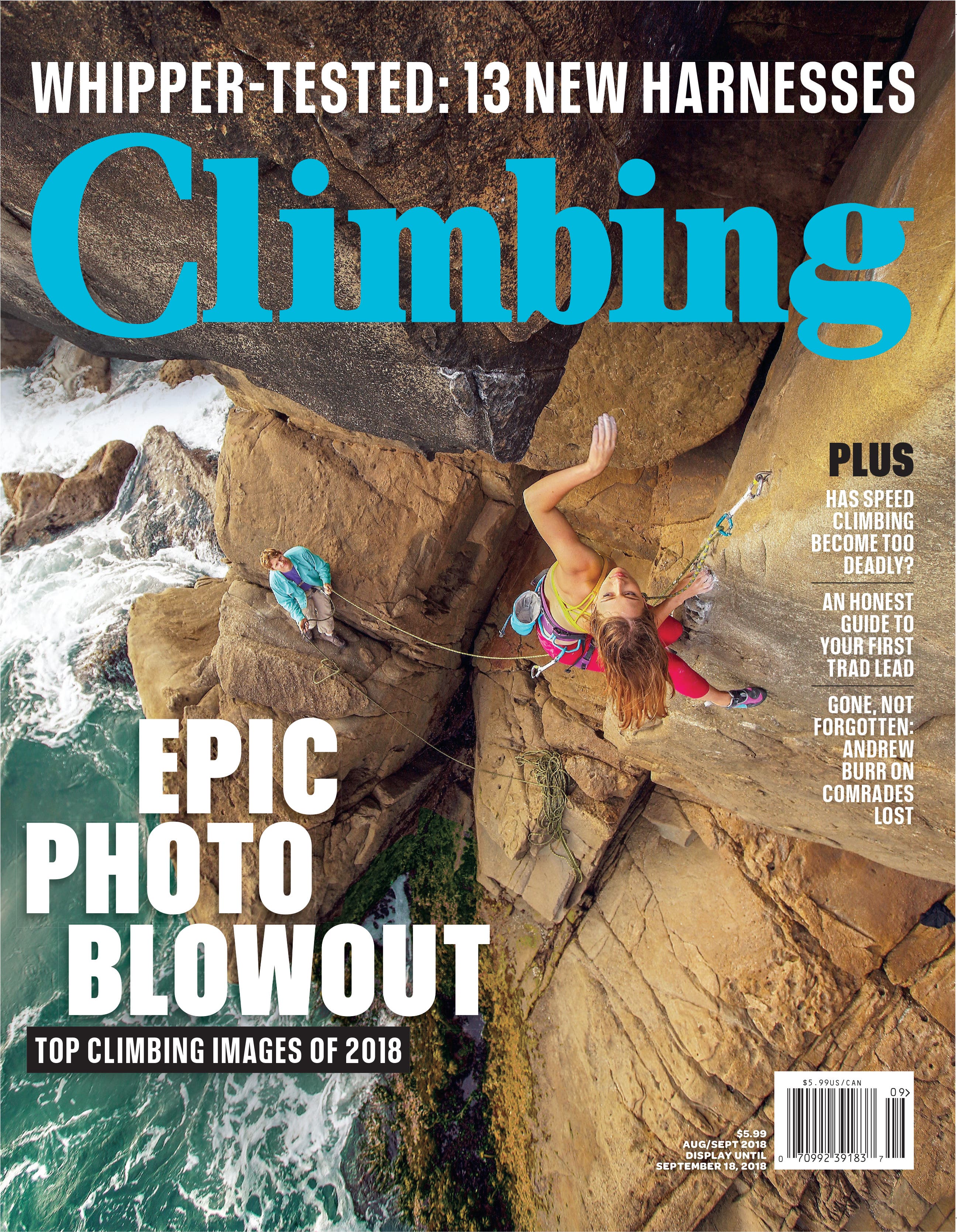

Photo Annual 2018

Eighteen arresting photos from our sport’s top photographers.

Get to the Point

Jim Thornburg’s 30-year quest to document the art of redpoint climbing.

Departments

The Approach

- Letters

- Poll: Posed vs. candid climbing photos

- Mini Revies: Three new books

Talk of the Crag

- Kkungu Spire: Worshipping the stone in the Ugandan jungle

- The Highs and Lows of El Cap Speed: Are big-wall climbers pushing too far?

The Place

- Climbing Made Public: Sport climbing comes to upstate New York at Thatcher State Park

- Access Report: Big wins and red flags

Unsent

- An Honest Guide to Your First Trad Lead

That One Time

- Shitstorm: Mikey Schaefer remembers an El Cap epic

Grasping at Draws

- Serious Climbers Only!: How the new school trains to train

Topo

- High Planes Drifter: The story behind one of Bishop’s most prized (and misspelled) problems)

Players

- The Dark Horse: Meet YOSAR beast and one time Nose record holder Jim Reynolds

Skills

- No Gym Membership Necessary: Six workouts you can do on real rock

- 3 Top Tips to Shoot Like a Pro: Elevate your photography from amateur-level butt shots to pro-level artistry

- Quick Clips: Quick fixes for common climbing problems

- Big-Wall Meal Planning: Learn how to stay fueled and hydrated for big-wall climbing

Faces

- An interview with climber and photographer Savannah Cummins

Essentials

- Harness the Power: How this complex life-saving device is designed and tested

- Big Review: 13 new harnesses, field tested

Cragsters

- Meet the Crag Royal