Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

Inner and outer worlds collide in an Arizona granite hideaway

Well lubricated with Pinot Gris, “Pig” careened around the campfire like a gyroscope. “Cochise Stronghold is a promised land,” he said, nodding preacherly. Shadows capered on the rock behind him, here in Joshua Tree’s overcrowded Hidden Valley Campground.

“It’s like Josh 25 years ago,” he crooned. Eyes feral and body lean, Pig had slept beneath a J-Tree boulder season after season to avoid the rangers. To his congregation of rock rats and weekending cubicle refugees, this bearded, jobless climbing bum was living the dream. His words carried weight.

“I’m done with it here!” Pig exclaimed. “I’m headed to the Stronghold.”

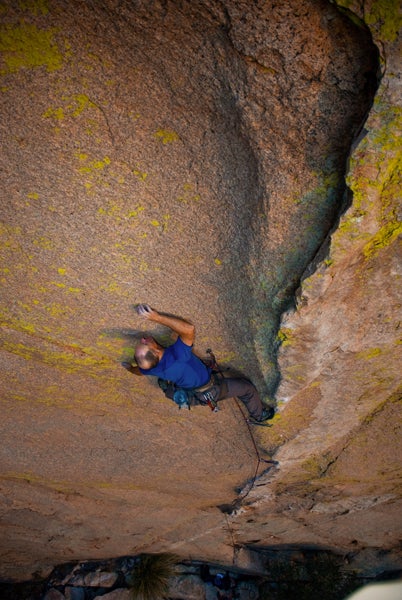

Pig continued: tucked away in Arizona’s southeast corner, he said, you find myriad golden domes punctuating the Dragoon Mountains’ ridges. It’s a granite Eden ripe with unique features like chickenheads and “alligator-skin” plates…if you could stomach 50-foot slab runouts above slung horns. Death-march approaches through boulder-strewn and brush-choked arroyos kept the masses at bay.

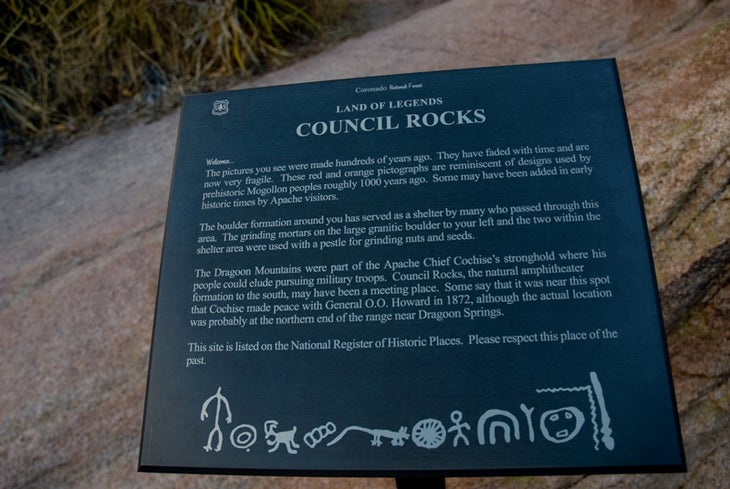

In the 1860s, 100 years before climbers came along, the rough domes served as a natural fortress from which the Apache launched raids on white settlers and Mexican villages, 50 miles south. If you listened closely, Pig promised, you could hear the wind-borne whisper of the warrior chief Cochise, whose body rests among the domes.

“The Stronghold” even the name intrigued me. As the years passed, the area and its Chiricahua Apache namesake, Cochise, remained a fascination, but I never put foot to gas pedal until now, November 2007, six years after Pig’s sermon. A few days into our Stronghold pilgrimage, my wife, Becca, and I drive the pockmarked dirt road to the Stronghold’s western edge, navigating off a tattered bit of yellow legal paper scrawled directions and a friend’s suggested ticklist. Rabbits crisscross the headlights’ beams. I expect to see a small campfire or a cluster of dented vehicles maybe even Pig holding court. But the road ends in darkness. The car-door’s report echoes like gunshot.

Out in the night, I feel the Stronghold waiting.

The next morning, Becca and I tromp up the hikers’ trail, and then veer across water-polished slabs and into scrubby creekbeds.

Two rugged canyons the East and West strongholds slice east to west across the Dragoon Mountains and are wonderlands of brilliant green and golden granite domes. The majority of the Stronghold’s climbing lies within a 2.5-mile radius, the exception being the 1,000-foot Sheepshead Dome seven miles south. Another seven-plus miles south of that, tourists gather in Tombstone to watch reenactments of the Shootout at the Okay Corral.

In the Stronghold’s center, 300- to 500-foot Rockfellow Domes tower above the other formations. We follow the creekbed, fight through spindly creosote, and traverse the domes’ feet, heading for Forest Lawn(5.9) and Pair A Grins (5.10), a two-pitch intro to the Stronghold’s notoriously thin climbing.

“You just got to believe the holds will appear,” the Arizona climber Eric Fazio-Rhicard told me days earlier as I whimpered up routes on the Out of Towners Dome, in the East Stronghold. I was freshly back from Thailand, forearms swollen and ego bulging. Watching the 50-year-old Fazio-Rhicard’s decisive foot movements through holdless 5.11 terrain, I realized my sport-climber toolkit was just so much baggage.

While Fazio-Rhicard is best known for his prodigious first-ascenting on Tucson’s Mount Lemmon, he’s also established Stronghold ultra-classics like War Paint (5.10), Sheep Thrills (5.11+), and the unrepeated slab Soul on Ice (5.12). Slab climbing is a cold science of patient movement, emotional detachment, and friction. On the hardest routes, Fazio-Rhicard will often wear larger, comfortable climbing shoes with thin socks. Larger shoes mean more rubber; more rubber means maximum friction. Skilled friction climbers might also place their palms against rock rather than reach for mediocre crimps in a variation on this surface-area hypothesis.

I bury numb fingers into the Forest Lawn’s well-defined crack (a bit of an anomaly many of the cracks here tend to be wide, grainy thrashfests). Next, on Fazio-Rhichard’s Pair a Grins, thin, but biting, face holds give way to tenuous friction and ever sparser bolts. A buffeting desert wind twists away the soft winter warmth and threatens to pry me from nonexistent holds. I breathe deeply, 15 feet out. It’s tempting to rush, pull close to the rock to stretch for a distant hold, but I rehearse the slab-climber’s mantra heels down, butt out, small steps. …

Twenty minutes later, Becca reaches the belay, and we scurry to the summit. From here, the Stronghold reveals itself. A granite maze lording over the Chihuahuan Desert.

For the latter half of the 1800s, the smell of gunpowder and blood drifted across southeast Arizona’s arroyos and alkaline flats. The region was locked in a struggle between white settlers backed by federal troops, and the Native American tribes. No tribe resisted the crush of “progress” longer or more fiercely than the Chiricahua Apache and their leader, Cochise.

While many tribes settled into reservations or government camps, the Chiricahua, infamous for their battle skill and unique brand of stomach-churning violence, continued to launch raids south into Mexico. Still, save a few isolated incidents, Cochise left the white settlers alone, a courtesy largely reciprocated by the Federal Government (at least in part because of the encroaching Civil War). Then, in 1861, an unknown raiding party kidnapped a rancher’s 12-year-old son; the Army quickly blamed and then imprisoned Cochise, who broke free and fled to the Stronghold, despite being shot three times during his escape. The ensuing violence escalated into a 15-year war of bilateral atrocities: any Apache man, woman, or child caught in the open was shot on sight. Wounded US soldiers were left lying atop red-ant mounds. Cavalry troops were found with their severed genitals stuffed in their mouths.

Through it all, the Stronghold remained a place of fragile refuge for the Chiricahua. From the tallest domes, scouts could spot riders moving across the dusty flatlands 30 or 40 miles away. A cavalry unit that ventured into the tight canyons would have to dismount and walk blindly toward ambush. In the Stronghold, Cochise and his Chiricahua warriors seemed untouchable.

“You know when you take your dog on a really good hike? You get home and the dog falls asleep. You can see him dreaming, twitching, reliving that perfect day,” says the Stronghold pioneer Dave Baker. “There were days when I’d return from the Stronghold and dream like that.”

These days, the Tucson local is happier backpacking than running it out on 5.10, but his memories of the Stronghold’s early days remain fresh.

In the early 1970s, Baker established many of the obvious classics the 400-foot jug haul What’s My Line (5.6 AO) and the immaculate finger layback of Forest Lawn. Yet for years, the imposing, lighthouse-like summit of the main Rockfellow Dome stymied his repeated efforts: there was simply no moderate way up. In 1972, Baker and friend Mike McEwen pulled off Kneed Me (5.10) five pitches of chimney and offwidth only to dead-end at a maze of stacked boulders with no clear path to Rockfellow’s summit. It wasn’t until a later trip that they ferreted out the devious path climbers now follow.

“When we did Kneed Me, that was when I realized ‘We can do things out here,’” says Baker, who also remembers the dozens of aborted attempts. Supposedly, the prolific Fred Beckey left the Stronghold in dismay after mistaking Baker’s numerous bail slings as evidence the area was climbed out. In the years following Kneed Me, Baker and his partners would usher in 5.11, with routes like the super-classic Abracadaver (5.11-). Baker also helped fostered a sense of community among southeast Arizona climbers.

While still in high school, Baker opened a small outdoor/climbing shop called the Alpine Hut in downtown Tucson, 80 miles west of the Stronghold. As much a social club for the 30-odd local climbers as a business, the Alpine Hut housed a three-ring binder known as “The Book” that held hand-drawn topos to the Stronghold; it passed from climber to climber until it finally disappeared. The tight-knit young locals developed into a collective of standard-pushers since dispersed taking the ground-up bolting ethic to its limits. No one pushed harder than Steve Grossman, whose routes were voyages in minimalism (see “You Think You’re Hard?” at the end of this article). Today, delicate and dangerous testpieces like his The Great Gig in the Sky (5.11 R) and You Bet Your Life (5.10+ R) are seldom done; maybe it’s because the former’s long crux pitch sports just one bolt and a few slung chickheads, while the latter’s final two pitches provide a only handful of bolts and gear placements.

Locals still organize the semi-annual “Beanfest,” which began in the late 1970s as a spontaneous, wild, tequila-swilling party. During the festival, the community gathers in the Stronghold for climbing and slideshows, all capped by the unique practice of “beaning” in which the event’s rotating volunteer organizer, the Beanmaster, marks each participant’s forehead with beans and sanctifies the ceremony with a tequila shot. It’s also a great venue for Beta: while Arizona guidebooks chronicle most of the classics, hundreds of climbs have never seen ink. A few locals prefer it that way.

Nobody is really sure how many routes Dave Des Champs, a Stronghold developer from Tucson, has authored, and he isn’t sharing. When I phone him, his words are clipped. When I ask Des Champs how many days a year he climbs in the Stronghold, he says, “About 100,” adding, “I don’t repeat routes either.”

The vast majority of the domes here require long, rough approaches. Many climbers lost in the Stronghold’s dense brush have likely ended up beneath a Des Champs route without knowing it. Des Champs started putting up Stronghold routes in the mid-1980s, on many of the lesser-known 50-to-250-foot domes. Such efforts imply a lot of bushwhacking and a penchant for solitude.

“I like not to see other people,” says Des Champs. “I don’t climb for the social aspect. I go where there is no chalk, no trail, no topo, no guide. If everything is known, there’s no adventure…the Stronghold is all about adventure.” Then, like a desert stream disappearing into sand, our conversation dries up.

The Stronghold is a perfect place for Des Champs and other outlanders. Save the Beanfest and occasional weekend campground surge, I find no real scene just climbers, wind, stars, and the ghosts of history.

It was nearly 140 years ago (1872) that Cochise used cunning and brutality to forge the short-lived Broken Arrow Peace Treaty with the Federal Government. This created a reservation extending from the Dragoons east toward Las Cruces, New Mexico. However, while many Chiricahua descended into the valleys, Cochise remained in his fortress until he died in 1874, from what scholars believe was stomach cancer.

Congress, believing the threat to the settlers had died with Cochise, refused to ratify the treaty that would have made the reservation official. The military rounded up the Chiricahua, no longer among the Stronghold’s domes, and placed them with other tribes on a reservation outside Tucson. Peace was brief free Chiricahua, led by Geronimo, continued to fight until their numbers dwindled; the remaining 38 were surrounded in 1886. Seeking to end the region’s chronic conflict, the US Government relocated the Apache to Fort Sill, Oklahoma. In 1913, the tribe returned to western New Mexico, to join with the Mescalero Apache. Some of the 3,300 tribe members still make visits to Cochise’s sublime natural fortress, but climbers are now the main visitors. Through our forefather’s penchant for violence, it seems, we have become the area’s caretakers.

“There are no half days at the Stronghold,” says the longtime Tucson climber Scott Ayers. “You know the rappels off End Pinnacle?” the 49-year-old asks, referring to a series of raps that weave deep inside a crevice between two domes. It seems one day he and a partner were trying to get a climb in before thunderstorms built. “Then the sky broke open, like someone sliced open one of those cheap, above-ground pools,” Ayers says. “Next thing I knew, there was water running down the rock. It was at my ankles, then waist. The rope was in the torrent. I thought, If lightning hits the domes, won’t the water carry the current?” (Similarly, while photographing this story in January 2007, James Q Martin began a shoot in decent weather, only to retreat an hour later in a blizzard.)

Ayers’ six-and-a-half-foot frame vibrates with enthusiasm, even for the near misses. Of the estimated 1,200 Stronghold climbs, Ayers has established more than 100 (comprising several hundred pitches) during his three-decade tenure. On a flawless December day, he trudges along in heavy hiking boots to protect his reconstructed foot, shattered in a ground fall. We share the approach trail; he’s off to work on another project. While the well-bolted sport climbs at the Isle of You in the West Stronghold or the East Stronghold’s small boulderfield make great quickie, late-afternoon destinations, most approaches are measured in hours, not minutes.