Deep Wisdom

"None"

A new way of thinking in the old South

I’m goin’ deep down to the backwoods of Chattanooga, to a place where bullets have the courtesy to stop and ask where you’re from, where snarling hounds smile through cotton teeth, and where the land is what it has always been promised to be.

I’m goin’ to an area where grapevines and briars part to let you pass, where blazed trails grow naturally on the hillside, and where bugs, rain, and humidity vacation in Colorado.

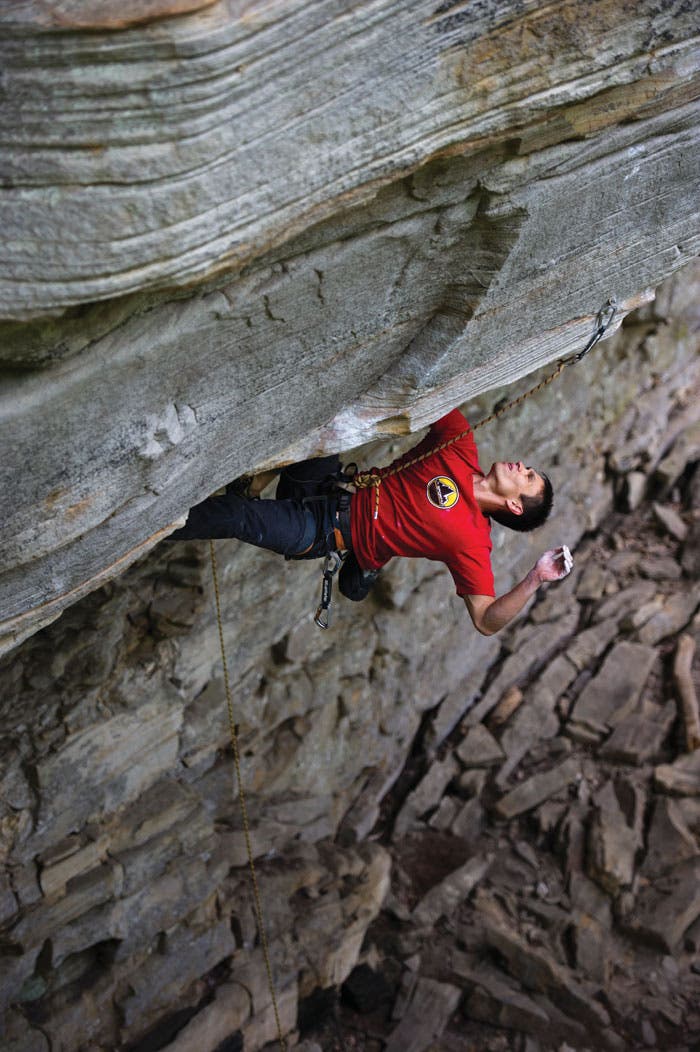

I’m goin’ to Deep Creek. At the crag that gravity built, the cliff is like a sandstone tsunami, white-capped with chalked jugs, permanently breaking in a marbleized swirl of overhanging blue and black stone. I’m goin’ deep down to the best sport crag in the Deep South. But I’m not sure I’ll tell you where it is.

If you’ve spent any time in the South, you’ve heard the same old story: Colorado has Rifle and its public beta classes, California has the Valley and its speed junkies, and the Deep South has its secret Edens of virgin sandstone—a quarter of which may be real rock, with the rest being overhanging rumors. The region is full of sandstone evangelicals who testify to the beauty and quality of their secret crags, but quickly revert to whisperings and winks when it comes time for full disclosure.

But before you dismiss us as intolerant hosts, realize that the issues affecting the Southern climbing community have long run deeper than personal choice. The climbing culture here is a direct artifact of the history of our land and the rock on it. In the Chattanooga area, we don’t have BLM or National Forest land. Instead, our serpentine gorges and rock-rimmed plateaus are subdivided by barbed wire and gates that proudly display Private Property in bright neon-orange. And as a result, the precarious balancing act of climbing on private land has been absorbed into our psyche, and cliques and secret areas have existed here for a practical purpose. But now, with Deep Creek, everything is changing.

“You look different,” he said.

“Yeah, I guess that’s what college does,” I replied, slapping my gut to cut the tension. The blood that moments before had been overpowering my forearms now seemed to have settled in my core, heavy and nauseating. I’d just been lowered from my first route at Deep Creek, and I stood 40 feet from the base of the overhanging wall, fidgeting like a dog on the end of a 100-foot nylon leash. I wasn’t supposed to be there.

“Rob,” said the grim-faced man, nodding to my partner.

“Hey,” replied Rob Robinson, feigning a genuine smile, unable to dodge the fact that he’d breached an oath of secrecy.

The two seasoned climbers locked eyes momentarily, and the volume of silence was deafening. Above Rob, a patchwork of light filtered through the canopy, illuminating 20 or so freshly scrubbed and chalked routes, each with a line of camouflaged bolt hangers spouting small streams of week-old bolt dust. The place exuded an aura of novelty and growth—a feeling that was rapidly evaporating as I faced the counterpart to everything that is fresh and exciting about the Southern climbing life. As many others had before me, I’d been caught climbing at someone’s secret area.

Discovered by climbers in 2007, Deep Creek saw its first routes created the traditional Southern way, by a small group of obsessed developers with an arsenal of hammer drills and a blood oath. For the better part of a year, local climbers managed to keep their presence in Deep Creek unknown while they harvested nearly 50 plum lines. But where there are secrets, there are ears to hear them. And as bits of information leaked, climber-on-climber tensions flared. Ironically, though, it was a passing hiker who spied some “unusual geology” and blew the whistle to the landowner, Tennessee’s Cumberland Trail State Park.

Immediately, the state implemented a ban on bolting as well as an “up in the air” policy on climbing the existing routes. In the past, most Southern climbers would have retreated and tried again on another cliff. But this time, inspired by access success at the nearby Stone Fort bouldering area a few years earlier, a group of Deep Creek developers, led by Chad Wykle and John Dorough, made a concerted effort to change the paradigm—this time, they would transition from users to stewards. The climbers at Deep Creek unlocked the door by walking the trails and cliff line with park offi cials to consider impacts from existing and future user groups. To open the door wide, the group petitioned the Southeastern Climbers Coalition (SCC) to raise funds and volunteer hours for Cumberland Trail bridge building and trail maintenance. And finally, to make sure the door never closes, climbers educated each other on hot-button issues for land managers like endangered flora recognition and fixed hardware standards.

No longer considered an irresponsible user group, in 2009, climbers succeeded in establishing a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with the Cumberland Trail State Park that has secured climbing and future route development at Deep Creek, as well as created a precedent for the future development of rock climbing on the extensive state lands to the north.

Since the MOU, new routes have resumed going in at a feverish pace. With the route count numbering over 150 and destined to grow to twice that number, Deep Creek has matured from a local crag to the Chattanooga sport climbing destination. Flowing water and oak-filtered sunlight create a climbing environment more reminiscent of a Zen garden than Tennessee wilderness, and, unlike many cliffs in the region, Deep Creek is gifted with a variety of angles and features.

On the far right (east) side of the crag stand white and gray, 80-foot vertical walls. Chicken heads, ribbed patinas, and the ubiquitous laser-cut horizontal edge populate 5.10s, 11s, and the occasional 5.13 you’d think were carved by the New River.

Further west, deeper into the tight drainage, are 50 or more classic lines that require a hike down the hill and away from the wall just to catch a glimpse of the overhanging headwall above. The cresting wall of 5.12s is split with horizontal hand jams that grab back as you plug in, forming a muscular conduit that refreshes the body and soul. As you continue upstream into the remotest sector, Deep Creek truly lives up to its name as the cliff rises straight from the streambed, with psychotically overhanging cave routes where, at times, whitewater and evergreens blur in your periphery as you hang way out above a riparian rock garden.

Even just a year ago, descriptions like these could hardly have been uttered aloud, let alone put into print. But the South is at a cultural crossroads that will forever alter how rock climbing is perceived in this region.

“Southeastern climbers have made and are making big changes,” says Matthew Gant, the SCC’s current president. “Historically, Southern climbing began as a rebellious and highly unregulated sport, drawing against-the-grain personalities, but as climbing has grown into a more popular and regulated activity, its user group has learned that it is necessary to work with those land managers that hold the keys to our vertical playgrounds. And this new accountability signifies a higher level of maturity and a more united climbing community.”

State and private landowners, bolters, gym climbers, boulderers—increasingly, we are migrating away from an us-and-them perspective and moving toward a greater sense of solidarity and cooperation. At Deep Creek, one such light-bulb moment occurred during the struggle to secure convenient public access to the cliffs. Although climbing had been legitimized through the MOU with the state, the closest street-legal parking only had room for two cars and required a four-mile hike to the crags; a more convenient access point was off-limits to anyone without explicit permission from a private landowner.

Inspired by the hard work of local access and development champions, Trevor Childress and I approached the Southeastern Climbers Coalition with a plan to purchase a 40-acre parcel just 10 minutes’ walk from Deep Creek, along with an agreement to provide the SCC with land sufficient for an ample public parking lot. After convening representatives from the SCC, Access Fund, and state of Tennessee, we petitioned the Southern outdoor community to consolidate behind a single banner of access for climbers, hikers, and general outdoor enthusiasts. And answering the call, the community raised more than $25,000 in just six weeks, resulting in a 30-car public-access parking lot and trailhead.

Everybody loves a secret—especially when you’re on the inside looking out. And secrecy, for many Southern climbers, has been a way of life, until recently. However, things here have changed and will continue to change. More than just a space of cleared ground and gravel, the parking lot and guaranteed access to Deep Creek represent a watershed moment in Southern access. Such successes are dismantling barriers and providing public meeting grounds where relationships are built without fear, and where the community subsequently grows by leaps and bounds. And while some people will always disagree, for me a crag is not yours because you found it, it’s not mine because I bolted it, and it’s not his because he climbed it—it’s ours because we all love it.

Cody Averbeck is a recent graduate of the University of the South and has spent a majority of his climbing life in and around Chattanooga. Having recently purchased a piece of land outside Deep Creek, he may be broke but considers himself a “sandstone billionaire.”

DEEP CREEK LOGISTICS

GETTING THERE: Before going to Deep Creek, visit seclimbers.org for updates on coded gate access to the parking area. The Deep Creek trailhead is 25 minutes north of Chattanooga. Take U.S. 27 north for 15.7 miles to the Thrasher Pike exit. Go left on Thrasher Pike and follow it to the stoplight. Take a right on Dayton Pike and go 0.7 miles to a stop light at Montlake Road. Turn left and follow Montlake Road up the mountain, passing Montlake Golf Course (home of the Stone Fort bouldering area).

From the Stone Fort, continue a mile on Montlake to a corner store and intersection with Mobray Pike. Take a right onto Mobray Pike, drive 0.1 miles to an intersection with Hotwater Road. Turn left and drive 1.9 miles on Hotwater Road to an intersection with Old Hotwater Road (if you go down the mountain, you’ve gone too far). Take the left onto Old Hotwater and go 0.1 miles to a private drive (11111 Old Hotwater Road). Follow the drive, staying left at the fork to reach the SCC parking lot. Please drive slowly and yield to local traffic.

ACCOMMODATIONS: There is no camping available in or around the Deep Creek area. Check out the Crashpad, a new hostel in Chattanooga that fills a longstanding need for affordable accommodations in the heart of the Scenic City. (423) 648-8393; www.crashpadchattanooga.com

GUIDE SERVICE: For guided rock climbing, hiking, backpacking, and hang-gliding opportunities in and around Chattanooga (including Deep Creek), visit lookoutside.com.

SEASON: Deep Creek’s cliffs are very shady, offering a complementary season to the Stone Fort, just three miles away. Climb at Deep Creek from late spring to late fall. While the summer months are notoriously hot in the South, the shade and swimming holes at Deep Creek make even July a time to send.

GETTING STARTED: For now, Deep Creek is not covered in any guidebook. Follow these instructions to find the crag. From the parking area, walk 5 minutes to intersect the Cumberland Trail, turn left, and follow the trail until it crosses Deep Creek and climbs a short hill to reach the cliff. Locate an obvious overhanging hand crack that passes a melon-size hole up high. This is Ga’jamit (5.11d), a classic.

Routes included in this selection begin here and move left: Knee Deep (5.11c) *** Starts 10 to 15 feet left of Ga’jamitWeigelizer (5.12a) ** Striking arête up high Weezer Route (5.12b) ** Gold streak Wicked Lester (5.12a) ** 5 feet left of the gold streak Willy vs. Dave (5.11b) ** Starts in obvious left-facing dihedral; 5.12a if you pull the fi nal mantel Mo’Cheeba (5.12b/c) *** Hard start through roof The Mole (5.12c) *** Best of the best; center of the wall, past bread-loaf pinch at half-height Deep Show (5.12d/13a) *** Classic; just left of The MoleThe Ear (5.12b) *** Climbs through a white shield of rock at quarter height

To start on easier routes, head to the Tea & Crumpets Wall, where you’ll find a number of 5.9, 5.10, and 5.11 lines. Instead of taking the obvious climbers’ trail up to Ga’jamit, continue on the Cumberland Trail, keeping an eye open for a climbers’ path and gray wall on your left, 5 to 10 minutes down the trail.

OPEN GATES Recent Southern access success stories

2010 West Side Boulders, Rumbling Bald, NC. The Carolina Climbers Coalition, backed by a bridge loan from the Access Fund’s Land Conservation Campaign, contracted to buy six acres filled with high-quality winter bouldering. Nearly two thirds of the $72,000 needed to complete the transfer has been raised. carolinaclimbers.org

Pendergrass-Murray Recreational Preserve, KY. In 2004, the Red River Gorge Climbers’ Coalition purchased this 700- acre area, which holds more than 500 climbs. Last year, the Access Fund refinanced the remaining $65,000 on the purchase with a low-interest loan, saving the coalition more than $10,000 in interest. rrgcc.org

2009 Steele, AL. This landmark Southern sandstone crag had been closed since 1987, but in September 2009 the Southeastern Climbers Coalition bought a 25-acre parcel containing more than 1,000 feet of cliff line; the SCC has raised nearly $55,000 to complete the purchase. seclimbers.org

Yellow Bluff, AL. The home of Alabama’s first 5.13 had long been closed to climbing, but in the spring of 2009, the SCC purchased the right side of the crag and reopened it to climbing. 2008 Laurel Knob, NC. The Carolina Climbers Coalition made the final payment on its purchase of this 1,000-foot granite cliff, protecting one of the East’s most adventurous climbing areas.