Eight Confessions of a Climbing Mom

This is one analogy that might surprise you: As I see it, motherhood is a lot like rock climbing.

Nothing truly prepares you for either: all the expert explanations, advice from well-meaning friends, instructional videos and manuals nothing does motherhood or climbing justice. I’ve learned this firsthand after nearly a decade at the first and two decades at the second.

In the end, climbing and motherhood come down to one thing: until you’re there yourself, perched precariously, staring wide-eyed and terrified around you, you have absolutely no idea what it’s like. Combining two such powerful and all-consuming life experiences has always challenged women. Which leads to my first confession. …

Confession No. 1: I no longer climb with my spouse.

November, 2007: It’s a glorious autumn day, and I’m out for a rare, precious bit of cragging in the Shawangunks. But I’m not with my husband, John, whom I met climbing. He’s home with our children, Grace, 9, and Matt, 6.

Before we were parents, John and I were each other’s favorite climbing partners. I started climbing in 1991, John a few years earlier. We met in the early 1990s at Manhattan’s first climbing wall and spent virtually all our free time outdoors we even aid-climbed in the Gunks during downpours (to the dismay of our poor dog, forlornly tied up below the cliff). But now we haven’t roped up together in six years.

It started as a safety precaution. When our oldest was a toddler, John and I found ourselves simul-climbing some very low-angled but grungy pitches to top out Whitehorse Ledge, New Hampshire. I’m cautious by nature, and this was outside my comfort zone. (I trip over schmutzy stuff on a flat trail.) As John and I moved up those easy slabs, I squelched thoughts of how awful it would be for our children if one of us died…but how unbearably awful (and irresponsible of us) if we both perished. I swore not to be in that position again.

Climbing separately is now pragmatic climbing is a time drain and someone must always be with young children. Like most of us, my family’s time budget is tight. John works a fullltime, corporate job with long hours, as I also did until a few years ago. Now I’m a full-time freelance writer and also full-time stay-at-home mom. (In the mom’s alternate universe, the percents add up.) A few years ago, John converted to more family-friendly, time-flexible, and condensed recreational activities first roped soloing, then bouldering. Now it’s exclusively gym bouldering and skateboarding.

Me? I tried solo-toproping with a Silent Partner and I can now do a 360 on a skateboard. But unlike John, who happily gets his outdoor fix at the skate park or snowboarding half-pipe, my heart lies in traditional roped climbing with a partner. Not that this is practical: we live in Connecticut, two hours from the cliffs, one hour from the closest rock gym. But who becomes a climber because it makes sense? Which brings me back to that autumn day in the Gunks: I’m with an old climbing pal who’s fun and safe but, most importantly, has grey hair, children, and a life outside the cliffs. Now that I’m a mother, I won’t climb with anyone who lacks a keen sense of mortality.

We’re on Modern Times, a steep, exposed classic that has the traditional Gunks sandbag rating of 5.8+ (but is 5.10 in the latest guidebook). If while seconding you pop on the crux, overhanging traverse, you swing out over several hundred feet of air. (You’re only 175 feet off the deck, but since the cliffs perch atop a hillside, you get the full-monty view of the countryside below.) There’s no easy way to pull back in, and if you fall again, you swing out, dangle, and end up back where you started.

Which is exactly what happens. I slip, swing, and dangle for an hour until I manage to aid my way up using helpful suggestions from a leader below. (My prussik technique is as rusty as my footwork.) When we chat afterward on the ground, the helpful leader is impressed that my climbing partner qualifies for AARP but still leads Modern Times. Then hearing I’m a mom, he exclaims, “Wow, now you’re the impressive one. I don’t know many moms who even still climb.”

Confession No. 2: Climbing as a mom is a lot harder than most women admit.

Like that helpful Gunkie, I don’t know many climbing moms either. Most of my gal climbing friends stopped after motherhood. (Some, inexplicably, stopped working out altogether.) I understand the dynamics, though. It can be hard to get excited to climb sporadically: you’re rusty, not used to exposure, and awkward on routes you previously aced. You watch other women smoothly leading your former trade routes, and now you’re fumbling to find the right-sized cam on a novice pitch.

If you somehow climb regularly, it’s most likely climbing is all you manage outside of motherhood (whether you’re stay-at-home or work an outside job). Both climbing and parenting suck up time faster than a telemarketer ringing at dinner.

The hard reality, even for women with supportive partners, is that most big-time parenting commitments typically fall onto mom’s side of the ledger teacher conferences, carpooling to school activities and play dates, buying school supplies and children’s clothes, packing lunches and snacks, scheduling doctors and dentist visits, organizing kids’ rooms and closets.… Some, like nightly tuck-ins, are incredibly heartwarming; some, like the infamous homework, just aren’t. Regardless, it’s all part of what you sign up for.

But it also all translates into less personal time (and less climbing time) for moms.

Confession No. 3: You need a “system” if you’re going to climb.

For good reason, my friend Jannette says, “The term ‘climbing mom’ is an oxymoron.” And this from a woman who’s developed the most creative and effective climbing system I know.

With two “tween” daughters, Jannette works four days a week, devotes weekends to her family, but keeps a sitter on call on Fridays, her climbing day. In the winter, it’s an indoor gym; when feasible, it’s outdoors. On weekends, she climbs with her daughters or organizes toproping groups with other climbing families. Periodically, Jannette sets up overnighters last fall, 75 of us descended on her house near the Gunks. (Some parents even managed to climb.) That Jannette pulls off being a good climber and a good mother is partly due to her talent and determination but also to her system, which is based on a dual-income household with disposable cash and time. It’s not one many moms can replicate.

Each climbing mom is on her own to figure out her system. Some use disposable income to hire sitters; others tap into local relatives or a climbing-mom childcare cooperative. (Nearby rock or climbing gyms help immeasurably.) But if you’re going to climb, you need a system incorporating at least one of those elements, ideally more.

And once you finally have your system working, be forewarned it can fall apart faster than you yell, “Take!”: your wonderful sitter joins the Peace Corps… your spouse starts traveling on weekends…your mom grows too frail to look after the kids. Or you become pregnant again. (Another reality: with each child, it’s exponentially harder to find time and energy to climb.) Or your child is now one year older, with different activities and needs.

And you’re back to figuring out your system all over again.

Confession No. 4: Maybe moms shouldn’t climb.

So far these confessions have involved logistics, avoiding the hardest, most obvious question should moms even climb? As the media invariably asks when a high-profile climbing mom dies, like Alison Hargreaves did on K2 in 1995: is it selfish and wrong to climb if you’re a mother? If you’re a mother and you die climbing, does that make you a bad mother?

Just because non-climbers ask these questions doesn’t mean they’re not legitimate. Undoubtedly, for children, one of life’s worst horrors is having their mother die, for any reason. Maybe a climbing mom’s friends and family find solace knowing she died doing “what she loved,” but that’s scant consolation to her children. Similarly, to a mother, the prospect of dying when her children are young is heartbreaking. This I know firsthand.

When my daughter was born, I nearly died in a statistically safe activity: childbirth. For 10 hours, I lay conscious but bleeding; doctors at a state-of-the-art New York hospital told me I had 50/50 odds. I’ll gloss over medical details but not the key point: this gave me a lot of time to think. And I realized that watching my children grow up is one of the greatest gifts. It’s an adventure beyond even climbing. It’s both the consolation for growing old and the reason I look forward (sort of) to growing old.

In short, if you’re a mother, there are many compelling reasons not to climb. Give my kids a choice: a dead mom fulfilled from climbing or a very much alive mom who’s frustrated and testy from not climbing, maybe even forced into unfulfilling activities (like shopping)? In a blink, I know they’d hand down a life sentence at the mall. …

Still, I climb. Leading to the next question: Why?

Confession No. 5: I don’t believe climbing is safe.

I don’t climb under the delusion that climbing is safer than everyday high-risk activities like driving. But I do believe the rewards from the way I climb now outweigh reasonable risks to my family and me. Climbing makes me happy…and climbing makes me a better mother. Both experiences share the same challenge at the center of a happy, fulfilled life: dealing with risk.

Dangling from the crux on Modern Times reminds me that scary endeavors can be safe and reasonable. Assuming I trusted my harness, knot, and belayer, my only risk was someone calling the Gunks rangers for a rescue talk about embarrassing! Conversely, a mundane endeavor can be risky driving, household falls, reality TV (the latter if you count risks to emotional health). With risk, perception versus reality is complex. This is invaluable to remember as a mother, because life as a mom is incredibly scary.

I’d had no idea, but moms face a veritable universe of terrifying threats to our children: molesters (local moms regularly email me warnings about suspicious sightings that turn out to be locked-out dads or magazine-subscription sellers), sabotaged Halloween candy (has anyone ever seen the infamous razorblade inside an apple?), routine fevers revealing obscure brain cancers, bike accidents, obesity, happy 8-year-olds morphing into sullen teenagers, sullen teenagers judging our adult lives. I know most of these (except the last two) are statistically unlikely for my own children but like most moms, I worry even as I maintain that a life bleached of risk is a life marginalized.

Give kids too little risk, and they’re not forced to strive, mature and achieve, and they end up like my cousin Howard never married, in his 50s, still living with his mother, working part-time as a substitute teacher. Give kids too much risk by encouraging or pushing them into pursuits beyond their current skillsets and we hurt them whether physically or emotionally, since they might down the road avoid reasonable challenges in school, socially, or in sports. As parents, we strive for a precarious balance between nurturing our children in the nest but encouraging them to take wing and fly. As climbers, we strive for that same balance between safety and challenge.

And so I still climb, though I stopped ice climbing years ago, lead routes below my already modest ability, drastically overprotect (to my partner’s amusement), and choose pitches with bomber pro and clean leader falls over easier but runout alternatives with crumbly rock and bone-breaker ledges. (A mom on crutches puts a crimp into the entire household.) I don’t climb much, but when I do, I try to share my joy with my family.

Confession No. 6: I hope my children won’t want to climb.

I know how much I’ve gotten from climbing. Before climbing, I was a completely urbanized, single Manhattan professional; through climbing, I discovered camping, the outdoors, and precious adventure otherwise lacking in my structured life. Most of all, I cherish the close climbing friendships, where being tied to another human on the rock captures what’s basic and truest about human relationships.

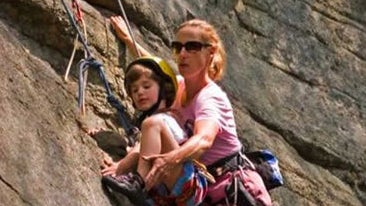

I hope my children find an activity that gives them similar zest, insight, and joy. I’d prefer it’s skiing or rowing rather than climbing I’d worry too much. But I’ve introduced them to climbing, believing that they need to makes these choices for themselves.

Confession No. 7: For now, I don’t mind climbing less.

It seems to me that whether a mother should climb is part of a bigger issue facing all mothers: should moms work full time? Stay home full time? Work part time, experiencing some benefits and drawbacks of both? It’s all about how to balance our personal needs with those of our family how to give so much that our children are nurtured, secure, happy, and beloved. But also how to leave something over, so our happiness isn’t sublimated to that of our children, leaving us squeezed dry and brittle, awful parents.

I have this dream that one day I’ll work out a system like Jannette’s, so I’ll climb once a week. But for now, I have these two adorable little creatures who are convinced I’m the most incredible being on the planet. Being a climbing mom, like being a mom, is about giving up a lot, giving out a lot, and getting back a lot. (Note: the order I rank these elements varies by the day.)

Confession No. 8: This article was incredibly hard to write.

This was one of the most personal articles I’ve ever written. My original intent was to cast the piece as a sociological, third-person overview. So I spoke with friends, interviewed many well-known climbers (moms and dads alike), and emailed a survey to climbing groups. Eventually, I tallied over 75 survey responses and 12-plus hours of phone interviews. (My deep thanks to all who shared.)

But when I showed my editor a draft, he told me something was missing. It needed to be real, personal, and ( Drat! ) confront uneasy truths I hoped to avoid, such as, ready? 1) Climbing and motherhood are pretty incompatible. 2) If your life’s goal, now and later, is to climb as much as possible, you probably shouldn’t become a mom, for odds are high you’ll be miserable and so will your children. 3) And I haven’t even touched on even more painful issues, such as eldercare or special-needs children

There are just no easy answers to the eternal climbing-mom quandary. All I know is that the day after my epic on Modern Times, I was back in countryburbia mom-mode at my daughter’s soccer game, exhilarated from the cliffs, exhilarated from watching my daughter running joyously on the field and my son playing on the sidelines with other children. So I fall back on this: childhood is short, the time to nurture and imprint is fleeting, but the rock will always be there. I’ll just keep doing my pull-ups so that I’ll be ready when my time comes to return to the rock, too.

Longtime climbing writer and Climbing.com Reader Blogger Susan E.B. Schwartz (theschwartzspot.com) wrote the bio of Gunks pioneer Hans Kraus ( Into the Unknown ). She is also a freelance business writer, ex-corporate exec and ex-scuba instructor, and now handyman, cook, chauffeur, homework cheerleader, and stuffed-animal surgeon. Schwartz is at present collaborating on a book with mountaineering dad Carlos Buhler.

While we worked with the author Susan E.B. Schwartz on her feature on what it’s like to be a climbing mom, we learned that her research was so thorough (and elucidating) that it would have been remiss not to share her other conclusions with readers. The following info is distilled from more than 75 survey responses and 12-plus hours of phone interviews.

Three Tips from Climbing Moms

1. Be Realistic

By not putting expectations on your climbing, you’re less likely to get frustrated or take unnecessary risks. You’ll also have more fun if you cut down on your grade, place more pro, and revisit classics you’ve climbed many times before.

2. Shift Focus

Channel your drive to the most family-friendly types of climbing, such as bouldering or sport climbing.

3. Take a Break

When your children are young, consider taking up other activities that give a similar sense of adventure, discovery, and peace but require less time.

Four Famous Climbing Moms Weigh In

- Big-wall climber Jacqueline Florine, who made the first (and only) female solo ascent of the Nose; married to Nose speedster Hans Florine and mom to Marianna, 7, and Pierce, 5: “I married this hotshot climber and now we never get to climb! I need to keep myself healthy so we can climb when we’re old codgers tootling about in a trailer. I also remind myself that I’m putting in the time with the children now so that we create a functional family and enjoy the whole process.”

- Mountaineer Kitty Calhoun, who made several first-female ascents of 8,000-meter peaks; mom to Grady, 12: “Once you’re born, you enter a world of risk. It’s part of life and what makes life exciting. There’s a lot to climbing besides the obvious, such as dealing with fear. … Life is not about the situation but how we deal with it.”

- Nancy Feagin, one of the top all-around American woman climbers of the 1990s; mom to Connor, 4: “If I were in my 20s and 30s without a child, I’d do what I did in climbing all over again. It was my passion. I couldn’t have lived behind a desk then. Now, it’s just not acceptable to me to consciously take risks that might get me severely injured or killed. I don’t want as much risk in my life now.”

- Lynn Hill, climbing icon; mom to Owen, 5: “Despite the inherent risks of climbing, I still love to climb and I never plan to give it up just because I’m a mother. However, I am much more selective about the risks I take. …One of the biggest challenges of motherhood has to do with juggling my time between work, climbing, and the daily responsibilities of raising a child. But whatever climbs and travels I might have missed during the formative years of my son’s life are small sacrifices compared to the love and richness Owen brings, and hopefully will contribute to others as part of the future generation.”

4 Realities of Climbing Parents

As part of my research, I emailed a questionnaire about climbing and parenting to 45 climbing pals, as well as to several climbing groups I found through the Web (including the Facebook site). Here are five key points that emerged.

1. Time is a major factor

Lack of time defines any parent’s life, but it’s intensified by climbing’s time demands. Moreover, it’s hard to share climbing time with young children at least happily for the children, if we’re being honest with ourselves about just how miserable/boring the crag environment can be for kids.

2. Climbing parents are in a certain amount of denial

Not one parent surveyed reported taking unwarranted risks or having found himself/herself in a hairy climbing situation about which he/she wouldn’t tell the spouse. Really? Maybe climbers who become parents tend to be the more responsible types, maybe the respondents didn’t give truthful replies, or maybe we don’t want to be honest with ourselves about climbing’s truly risky nature. A final possibility is that because so much in climbing is internalized, something risky for one climbing parent could feel perfectly reasonable for another.

3. Some of us climb more safely after becoming parents

But it’s not because we suddenly decide to climb lower grades, wear helmets, or back up rappels. Instead, we develop more self-awareness, maturity, and better understanding of why we climb, which helps us stay honest in risky situations.

4. No pattern emerged regarding whether climbing parents want their children to climb

Some said absolutely yes (I want to share climbing with them…I don’t want them to miss what I’ve experienced ), some said no (I hope not…too risky) , and some hedged. Interestingly, this held equally true among moms and dads, and professional and recreational climbers, including parents known for bold, runout ascents.