Hemp Rope Classics

"None"

8 excellent routes from pre-World War II

You’ve said it while climbing a classic route—after an exposed traverse, an unprotectable chimney, or a spooky runout: Wow! Imagine climbing that without cams or nuts, sticky rubber, or any beta. Without even a nylon rope, harness, or belay device—instead, you’d have to wrap a rough, natural-fiber cord around your body to hold a fall.

The saying goes that there are no old, bold climbers, but there are still old, bold climbs that demand respect. Prior to World War II, most American climbers’ focus was on alpine climbs like Stettner’s Ledges on Longs Peak, Colorado— a 5.8 multi-pitch with serious weather and other hazards, put up more than 80 years ago. But to prepare for mountain routes like these, climbers went cragging, developing the techniques of rock climbing—and leaving classic climbs you can still do. Want to follow in some legendary footsteps? History class begins now.

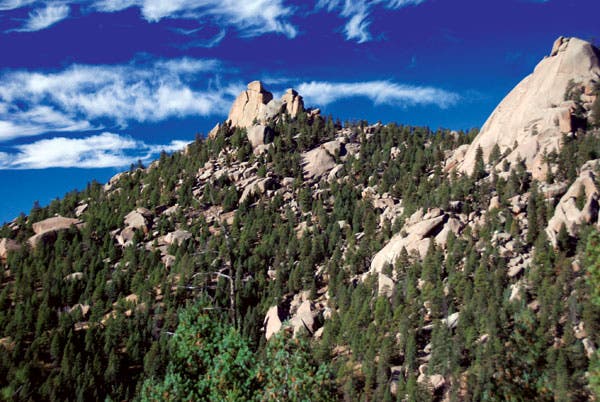

1924: Ellingwood Chimney (5.8, 2 pitches), The Bishop, South Platte, Colorado FA: Albert Ellingwood, Agnes Vaille, Stephen Hart

Albert Ellingwood was one of Colorado’s earliest and boldest climbing pioneers, putting up notable routes like Ellingwood Ledges (5.7) on 14,197- foot Crestone Needle and the difficult San Juan Mountains choss spire Lizard Head, nowadays rated 5.8 R. If you get a little sketched stemming up the historic Ellingwood Chimney, just remember that after Ellingwood led it for the first time, placing no gear, he downclimbed it after lowering his partners.

The Bishop is located in Colorado’s South Platte area, 3.8 miles south on Jefferson County Road 96 from its intersection with Jeffco Road 97. Ellingwood Chimney is the obvious feature in the corner on the west face of the Bishop, left of an enormous roof. Chimney up and attempt to gracefully pull over the chockstone on pitch one, or just belly-flop onto it. The second pitch has a cavernous chimney and then a wide crack to anchors on the righthand summit.

-

Descent: Rap with two ropes, or one rope to a rap station in the Bishop Chimney (just to the left of Ellingwood Chimney).

-

Rack: Cams to 4 inches; a 5- to 6-inch piece is good to protect the second pitch.

-

Guidebook:South Platte Climbing: The Northern Volume, by Jason Haas, Ben Schneider and Craig Weinhold (fixedpin.com)

1929: Whitney-Gilman Ridge (5.7, 2 pitches), Cannon Cliff, New HampshireFA: Hassler Whitney, Bradley Gilman

When people say “Whitney-Gilman,” they also usually say “exposure,” and you’ll know what they mean midway through this East Coast mega-classic. Cousins Whitney and Gilman first climbed this obvious spine jutting from New Hampshire’s Cannon Cliff not only without cams, but without pitons—they just stopped to belay a dozen times, whenever they found a decent ledge. Remember that when you step out onto the right side of the ridge on pitch three and feel all that air under your feet. Whitney, a distinguished mathematician, might also hold the claim to being America’s first boulderer—he explored the blocs of Sleeping Giant, Connecticut, while a student at Yale in the mid-1920s.

Robert Underhill and Kenneth Henderson (who paired up to pioneer several Tetons classics) repeated the Whitney-Gilman. Underhill called it “a long series of passages of great technical difficulty, high exposure, and dubious outlet.” The men hammered in the section of iron pipe that still marks the most exposed section on the nowfamous Pipe Pitch.

The Northeast’s most famous climb begins about 50 feet north of where the arête meets the talus. Follow cracks and fixed pins up five pitches, staying close to the ridge; if you find yourself on loose rock, you’re probably too far left. The crux is on the third pitch, where you’ll step around the corner to the right and look down on the tremendous exposure and spot the infamous pipe. Plenty of variations are possible, but staying to the true 1929 line will keep the climbing 5.7 or easier. Get here first on a weekend or come on a weekday—there’s a fair amount of loose rock on this alpine route.

-

Descent: Follow the trail off the top into the woods, and it will eventually head left and down to a bike path.

-

Rack: Standard rack

-

Guidebook: Rock Climbing New England, by Stewart Green (falcon.com)

1942: Brinton’s Crack (5.6, 1 pitch), Devil’s Lake, WisconsinFA: Bob Brinton

Bob Brinton’s name doesn’t appear nearly as prolifically in climbing history books as Fritz Wiessner’s, but this single pitch at Devil’s Lake forever marks the day Brinton bested the wellknown pioneer. By 1942, the legendary Wiessner had put up bold new routes in the Gunks, Cannon Cliff, Devils Tower, and other areas, and climbed to within 700 feet of K2’s summit. But he backed off an attempt on this 5.6 line in Wisconsin. Plenty of leaders do the same thing, at the same spot Wiessner did: a spooky and committing traverse across bad hand holds. After Wiessner bailed that day in 1942, Brinton climbed to his high point, devised a traverse, and stamped his name on this classic-of-all-classics at Devil’s Lake.

There’s no shame in first toproping this heady and sandbagged 5.6 on Brinton’s Buttress—that’s the style at the Midwest’s most famous climbing area. Start in the wide crack near the corner of Brinton’s Buttress, and when the crack runs out, take a deep breath, lean in, and trust your feet at the “stepacross” move. Jam up an exposed crack to the top.

-

Descent: Walk off.

-

Rack: Lots of 2- and 3-inch pieces

-

Guidebook: Climber’s Guide to Devil’s Lake, by Sven Olof Swartling and Pete Mayer (uwpress.wisc.edu)

1944: Yellow Ridge (5.7, 2-3 pitches), Shawangunks, New YorkFA: Fritz Wiessner, Ed Gross, Ann Gross

Fritz Wiessner “discovered” the Gunks for climbers in 1935, spotting the rock all the way from the Hudson River while climbing at Breakneck Ridge. Wiessner first explored the cliffs at Millbrook (the first-ever Gunks route was the seldom-climbed 5.5 Old Route at Millbrook), and then put up classics everywhere else. His name is all over the Gunks history books, on routes like High Exposure, Frog’s Head, and Horseman. He waited until 1944 to put up Yellow Ridge, arguably the best 5.7 at the Gunks: a long exposed traverse, classic “Gunks 5.6” roofs, and an offwidth start that will take you back to the early days of climbing.

Yellow Ridge lies just a few minutes from the road at the Near Trapps. The route works its way up a tricky face down and right of an offwidth about 20 feet up the wall. Get into the business on the left side of the offwidth, and then set up a belay to minimize rope drag. Climb the corner above for 20 feet and traverse out 50 feet left to a belay, then head left to the nose for your dose of exposed and steep climbing to the top.

-

Descent: Walk off via the cliff-top trail to climbers’ right.

-

Rack: Standard rack. A 3- or 4-inch piece works to back up the piton on the offwidth.

-

Guidebook:The Gunks Guide, by Todd Swain (falcon.com)

1944: Conn’s East (5.6, 3 pitches), Seneca Rocks, West VirginiaFA: John Stearns, George Kolbucher, Bob Hecker, Jim Crooks

The U.S. Army’s 10th Mountain Division is famous for its February 1945 nighttime operation to take Riva Ridge in the Apennines, Italy, to the surprise of the Germans, who thought Mt. Belvedere unclimbable even during daylight. Much of the 10th Mountain Division’s stateside training took place at Seneca Rocks and other nearby crags, where they hammered in more than 75,000 pitons—many of which have never been removed, giving one section of rock at Seneca the nickname “The Face of a Thousand Pitons.” This route, boldly traversing a huge chunk of the east face of Seneca’s South Peak, is a mark of their legacy—it was climbed for the first time just a few months before the assault on Riva Ridge.

Conn’s East—named for American climbing pioneers Herb and Jan Conn— begins about 50 feet left of the twin Castor and Pollux cracks on Upper Broadway Ledge on the East Face of South Peak. Climb the right-leaning ledge system past a tree, and continue up and right to anchor bolts. Pitch two is where you get your old-school money’s worth, hanging out over big exposure as you move across a bulge, and telling yourself that it’s “only 5.6” until a couple of big jugs appear. Finish out the third pitch to join Gunsight to South Peak and then scramble to the summit along the ridge.

-

Descent: Scramble down north along the summit ridge to a notch at the top of Alcoa Presents, and do three single-rope raps to Upper Broadway.

-

Rack: Standard rack

-

Guidebook: Seneca: The Climbers Guide—Second Edition, by Tony Barnes (earthboundsports.com)