L’autre Côté de Fred Rouhling

"None"

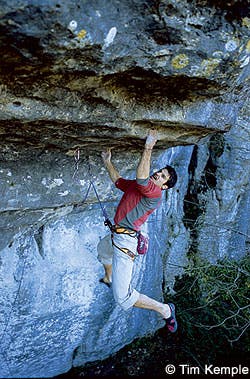

Fred Rouhling moving through the chipped section of his route L’autre Côté du Ciel, Eaux Claires, France.

Cheat! Liar! Over the years, many climbers have become objects of derision because the claims they made did not pass muster. Once the negative publicity gets rolling, it seems there’s no stopping it. In the sport-climbing world, perhaps no man has received as much bad press as Fred Rouhling, a Frenchman who made the news in the mid-1990s. In 1995, his infamy hit international proportions when he claimed the 9b grade for one of his routes, Rouhling’s other hard routes were almost as controversial. More recently, he’s been climbing hard again, and last winter, we sent a pair of American climber/journalists to visit him and see if they could get the real scoop.I think I have finally caught Fred Rouhling in a lie. There appears to be a chipped hold on Akira, a route Fred says he did not manufacture. I call Rouhling over and point out the hold. I ask him to climb this section of the route.Fred takes a moment to look over the section. He examines the tick marks left by whoever has been trying the route, pantomimes a few sequences, and sits down to put on his shoes. Tim loads some film while I move a few pads around, wondering how I should feel if I have indeed caught Fred in a lie. I decide that’s his problem, and wait to see if he needs the suspect hold — or if he can climb the thing at all. Rouhling stands up, chalks his hands, and begins climbing.

L’autre Côté du Ciel (The Other Side of the Sky).

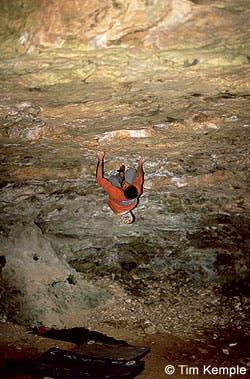

Almost ten years ago, the French sport climber Fred Rouhling claimed to have climbed this unusual route, near the tiny town of Vilhonneur in western France, and gave it an unprecedented rating: 9b, or 5.15b. At that time, even the 9a grade was barely accepted, and Rouhling’s claim was met with scorn. The line — out a huge roof within bouldering distance of the ground, then up a short wall — might be described as a long, hard boulder problem linked to a very short 5.13b. Most Americans immediately dismissed the route. In 1995, top-flight Americans were just inching into 5.14b, and while we knew that European climbers were stronger, we just couldn’t stomach the thought of an unknown Euro besting us by a whole number grade. Jibé Tribout and Ben Moon, the world’s best sport climbers, were not too enamored with the idea either — and said so. Rouhling found himself at odds with just about everyone. Some skeptics said that Akira could not be the hardest route in the world; others said that didn’t matter because Rouhling hadn’t climbed it anyway. Akira was buried in the small print and Rouhling became climbing’s poster boy for ego-driven, sponsor-pleasing, dubious achievement. Some climbers, once called out for cheating, quickly fade from the scene. But eight years later, Rouhling is still climbing hard. In 2002 he climbed Fred Nicole’s super-slab Bain de Sang, confirmed at 9a (5.14d). For most of 2003 he was the world’s third-ranked boulderer on the website www.8a.nu, having climbed a V14 and eight V13s last spring. Most recently, he made the second ascent of a Swiss V14 called Eau Profond — in fifteen minutes. These ascents of well-known challenges were witnessed and seen as credible enough to be reported in the international media.

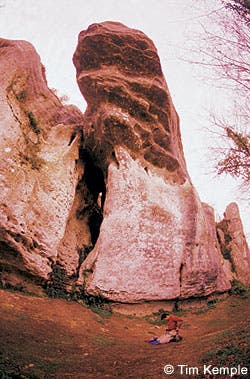

L’autre Côté du Ciel, Eaux Claires, France.

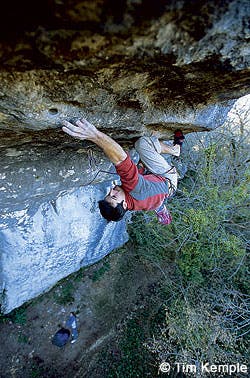

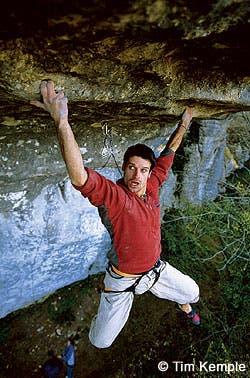

I was intrigued. If Fred Rouhling was responsible for the hardest section of rock ever climbed, why don’t we hear of more standard-setting routes? If he was dishonest, why does he continue to climb so publicly, in the face of such harsh criticism? And most important: Akira — did he, or didn’t he? After a few months of e-mails, I arranged to visit Rouhling in France to find out. I have just spent a week kicking around several European climbing areas with photographer Tim Kemple. The climbing has been great, but it seems like the main focus of our trip has been gossip. Everybody wants to talk about Fred Rouhling, and we are keen to listen. At least half the people we speak to are convinced that Fred is a shady character and/or he didn’t climb his routes. I have learned that Rouhling is six-four or six-five, with a huge wingspan. “Plus-six or -seven ape index,” says one guy who professes to know Rouhling from back in the day. Another climber says that his routes are just a bunch of huge, chipped moves that he could only do because he’s so tall. I hear that Rouhling climbed Akira and then filled in holds so that it would be harder for others. I hear, from American climber Dave Graham, that Rouhling could not do the V7 moves on the bottom of Realization at Ceüse. I have heard enough to feel that the best-case scenario for Rouhling would be that he climbed his routes, but that they are freakish gymnastic feats possible only for enormous climbers with huge wingspans. As we pull into the parking lot that is our rendezvous point, things do not look good for Fred Rouhling. I step out of our tiny rental car just as Rouhling pulls over in his VW Caravan across the road. French police wearing little chef/police hats drive by in their minuscule patrol car. They glare at the strange-looking people talking in the parking lot late at night and almost drive through a red light. We wave to Fred and he waves back. As he jogs across the road to meet us, however, something is wrong. At first I can’t put my finger on it, so I smile as we exchange pleasantries. As he gives us directions to his parents’ house, I realize the problem: He’s too short. Later, we measure his height and reach. He is five feet, nine inches tall with a plus-one-and-a-half ape index. The myth begins to unravel. Rouhling grew up in the tiny farming hamlet of Le Panissaud, about 100 kilometers northeast of Bordeaux. The neighboring village of Vilhonneur is home to a limestone quarry that, locals say with great pride, supplied the blocks at the base of the Statue of Liberty. Twenty minutes away is the town of Angoulême, where gray limestone bulges overhang many of the roads, forming a quiet little climbing area of several dozen crags known as Les Eaux Claires. Literally translated to mean “The Clear Waters,” Les Eaux Claires is one hell of a climbing area to have in your back yard. The longest approach walk is a level hundred meters, leading to bullet limestone swells rising fifteen to twenty meters, often more overhanging than they are tall. And the style? Forget about stereotypical French drop-knees and the like; if you want to be successful at Eaux Claires you need two steel-strong fingers on each hand and shoulders to match. The climbing is all about big moves between small pockets — and of this, Rouhling is a master. Rouhling tore through the grades as a teenager, establishing his first 8b (5.13d) at the age of nineteen. In the early 1990s he went to college in the South of France, which was the place to be worldwide for hard sport climbing. While there, he established two early 8c routes, UFO in the Calanques near Marseilles and Les Spécialistes Direct at the Verdon Gorge. When Rouhling returned from college in 1993 he was sick of the technical endurance style that had made French sport climbing famous. Tired of using his feet, he sought out — or created — routes at Eaux Claires that didn’t require them. The first was Hugh, a sixty-foot double-overhanging bulge (with the graffito “HUG” painted in four-foot-tall letters at its base). After his first ascent he felt that he had made the route too easy, so he filled in some holds, made others worse, and then climbed the route again, resulting in some incredible dynamic moves — and his most heavy-handed manufacturing job. He rated Hugh 9a (5.14d), at a time when there were two or three other 9a’s in the world. Next for Rouhling was Akira. The huge roof climb was less than a kilometer from his parents’ home and only 200 meters from the edge of the local quarry. In a slightly different world, Akira might be holding up the Statue of Liberty. The line runs from the deepest corner of the cave directly out to the mouth. It is sixty-five feet long and rises perhaps ten vertical feet over that length. You can reach any point on the first forty-five feet of the route with a four-foot stepladder, which is exactly what Rouhling did in 1995. For three consecutive months, he worked out the unrelenting dynamic bouldering movement. Pinches, slopers, crimps, and pockets lead to a jug rest near the lip of the roof where, on “redpoint,” Rouhling was handed a rope to lead the last fifteen feet of climbing. He gave Akira 9b (5.15b); that grade would still make it the hardest section of rock climbing ever done by anyone, anywhere. And he claims that none of the holds was manufactured. Rouhling’s last hard first ascent follows a jutting prow next to Hugh, L’autre Côté du Ciel (The Other Side of the Sky). The crux bulges involve a series of campus moves on pockets that bend one’s perception of how the human body is supposed to move. The final sequence is something to behold: Big pocket moves lead to a five-foot crossover that positions the climber facing away from the rock — a more impressive version of Tom Cruise’s memorable move in Mission: Impossible 2. Rouhling climbed L’autre Côté du Ciel in 1996 and feels that route, at hard 9a, is his second hardest. “Of course it is natural.” The glint in Rouhling’s eye gives away the punch line before he says it. “Naturally drilled.” He finishes with a shrug of his shoulders. Fred Rouhling chipped holds on some of his hard routes, but his tactics were typical of that era in France. Many of the most famous hard French sport routes, including La Rose et la Vampire, Bronx, and Super Plafond, have some degree of chipping and/or gluing on them, and some are completely manufactured. Even in the United States, many hard, classic routes rely on chipped holds — The Phoenix in Yosemite, Just Do It at Smith Rock, and Hasta la Vista at Mount Charleston, for example. Rouhling was hardly the only one chipping routes in the mid-1990s, but once he stepped outside the box and claimed 9b for Akira, his methodology received an unprecedented level of scrutiny and he became the whipping boy for the shady practices of a whole community. Rouhling now thinks chipping was a mistake. His peers were doing it, and while it seemed natural at the time, he has traveled a lot since then and broadened his vision. The last hold he chipped was on L’autre Côté and he’s not proud that he did it. When describing Hugh, he constantly refers to it as “dirty.” While Rouhling has changed his mind about chipping, you can see the joy in his climbing when he revisits his old routes. His eyes light up and he literally bounces from hold to hold, feet swinging, remembering the era and the place.

The famous Akira, near the Rouhling family home in Vilhonneur, France. The sixty-five-foot bouldering/sport line is one of only two climbs in the world rated 9b.

The same gossip that said Rouhling was a giant also says he’s a recluse, so I expect him to be reticent about showing us his routes. But as we sit down for dinner, the first thing he asks is, “Do you want to go to Akira in the morning?” Over the next four days, I find Fred Rouhling to be the most open, accessible person I have ever met. You can ask him anything and he will do his best to give a complete answer. So we do. Less than an hour after meeting him, in front of his parents (whom he is visiting for the holidays) at the dinner table, we are quizzing him about his routes, his chipping, and his detractors. We repeat the allegations of famous climbers, we ask him tough questions, and we repeat them expecting discrepancies in his answers. There are none. “When people say that I do hard routes in my style, I can say nothing,” he says. “They are all in my style, and they are here, not in the South of France where it is easy for everyone to see them.” Rouhling flat-out refuses to say anything negative about anyone. And as far as I can tell it’s not that he’s holding his tongue; he simply harbors no animosity. That someone who has been so viciously criticized would not hold a grudge is beyond me. Tim and I leave for the night stuffed with fine French food, more intrigued than ever. We are psyched to see Akira first thing in the morning. Our first attempt to see the route nearly ends in failure. The neighborhood drunk has set up shop on the main trail and he works himself into a violent rage about our presence there. Eventually he begins shouting about getting a gun, so we leave. We backtrack and sneak through some brush before ducking under a narrow arch and stepping up into a large cave with a flat roof. Our French friend Philippe stands by the mouth of the cave shifting nervously from one foot to the other. Every sound of a stick breaking or a squirrel scooting up a tree sends Philippe jumping. Rouhling shows us sequences and points out places where he leveled off the landing. He says he was very scared while doing the moves because he had no pads and the limestone is not of the highest quality. Rouhling points out the many holds he glued. In some places it’s a bit ugly. But though the glue is copious, there do not appear to be any chipped holds. After our brief inspection we decide that it will be less stressful to come back another day and bring the drunk a bottle of wine. Over the next few days we photograph Rouhling on numerous hard routes, including Hugh and L’autre Côté du Ciel. He repeats large sections of the routes many times to make sure Tim gets the photos he wants. Early in the first day of shooting Rouhling rips a huge hole in his middle finger while campusing on one-finger pockets. His finger is squirting blood, and I am concerned that our investigation will come to an abrupt end. Instead, Rouhling stuffs the hole full of chalk until the bleeding stops and asks Tim if he needs a different angle for the shot. Later that day Rouhling climbs half of Hugh on his first go. His climbing reminds me of Chris Sharma: He messes with his feet, seeming unsure where to put them, until he appears to grow tired of trying and proceeds to campus huge moves as though that is the easiest option. On L’autre Côté du Ciel, Rouhling does his Tom Cruise impersonation over and over until Tim has the shot he wants. Rouhling is spent (he is doing the route with no warm-up, on his third day on), and he asks to come down. I tell him that I have to see the section one more time. Fred smiles and chalks up. After a series of big moves, he hits a finger-bucket, fully extended, with his left hand. He cuts his feet loose again and plants his right hand flat on the roof above his head. There is no hold there but the move checks his swing. He then executes a monster right-over-left crossover and unwinds into the Mission: Impossible move, facing away from the cliff. He tries to continue, but this time the 180-degree spinning campus from the two-finger pocket is just barely too much for him. He hits the next sloper but can’t hold it. His body slams back down and he is left pinwheeling from two fingers of his right hand. He holds this position for a few seconds pondering another one-arm pull-up, as Tim and I shout at him to let go. It is clear to me that this route is well within Rouhling’s capabilities.

Rouhling below the bulging L’autre Côté du Ciel, Eaux Claires.

Word has circulated around Angouleme that Fred Rouhling has come home and is climbing on his routes. While he’s climbing, cars park on the road below and people sit on a low bridge where they can get a good view. When Rouhling comes down, several people approach him. Some are old friends from his childhood, happy to see him and a little pissed off that he didn’t call to say he would be back in town. Rouhling says that when he climbed Hugh and Akira, nobody knew who he was and there were no crowds, but that for L’autre Côté there were people who came to watch every day. He says that this was his best first ascent. He says that for him, climbing is better this way, with more transparency, and that if he could change one thing from his early hard climbs it would be for them to have been more public. He enjoyed his recent trip to Switzerland when people came to watch him boulder. After the photo shoot we again retire to Fred’s parents’ home for dinner. It’s clear that Fred’s children, Hugo (age three) and Chloe (age five), and his wife, Celine, are the most important things in his life. He is equally close with his parents and over dinner we find out one good reason why. In 1995 Celine sustained a serious spinal-cord injury from a soloing fall, and the couple stayed at Fred’s parents’ house for three months while Celine was recovering from emergency surgery. While caring for Celine, Rouhling slipped away for a few hours each day to work on Akira. When he talks about working the route, you can see him relax, remembering the momentary escapes from worrying about Celine. When she was well enough, Celine came out to belay Fred on the first ascent of Akira. In 1996 Rouhling climbed L’autre Côté du Ciel, but over the next few years it was difficult to find time for climbing. First came the children, and then Celine was forced to undergo brain surgery for an illness unrelated to her fall. She has been fine for many years now, but the experience has put Rouhling’s priorities in order: family first. Tim and I are growing comfortable hanging out with Fred’s parents. We drink cognac and wine late into the night, babbling in our broken French. When we are alone, we shake our heads in disbelief. It seems that almost nothing that we have heard or read about Rouhling is turning out to be accurate. He is scrupulous in pointing out his mistakes, and in four consecutive days of climbing, Rouhling makes exactly zero excuses for any failure. It is a refreshing, pressure-free way to climb. Success and failure feel less important, and the process of trying becomes a lot more fun. Tim and I speculate about how there could possibly be such a large information gap between the Rouhling gossip and our experience of the Rouhling reality. We decide that it’s because Rouhling is not a guy who plays the game. He does not try to change public opinion about himself. He harbors the distinctly un-American view that the routes themselves are more important than the individual who climbs them, and seems to like that his chosen sport permits people to achieve at a high standard without becoming public figures. “Climbing is good because it is not like tennis,” says Rouhling. “If I practice tennis for the next year it does not matter how good I become, because there is almost no chance that I can go and play against the best tennis players like Pete Sampras. But climbing is different. Tomorrow I can go and get on Realization if I like. The hardest routes are always there and anyone can go and try them as they like. … So when people say things about me, it is OK. Because no matter what they say about me, the routes are still there, and if they like they can go and try them.” The last day of our visit, we go back to Akira. Fortunately, the drunk Frenchman is nowhere in sight. There are tick marks and chalk all over the route. Somebody has been here, so maybe the rumors that the Spanish ace Dani Andrada has been climbing here are true. The bulk of the route is about ten feet off the ground and totally horizontal. After ten feet of moderate climbing, the next twenty feet zigzag through the most difficult moves on the route. Fred tells me he feels this section could be V14, judging by the boulder problems he’s done recently. After the initial boulder problem, the route fires straight out the center of the cave. Rouhling says that although he originally thought this part was 5.14a, he has heard that Andrada found better Beta and it’s really 5.13d. At the mouth of the cave there is a long horizontal break where Fred was handed a rope for the last bit of 5.13b. (Rouhling switches between bouldering grades and route grades to distinguish between the difficulty of a shorter sequence and the difficulty of a whole section of the route. Therefore he says that one could call Akira V14, to a bit of 5.14a, to a bit of 5.13b — or simply 5.15b.) As we stretch out, I start an argument about whether Akira is a boulder problem or a route. Rouhling concedes that if he were to do it now he’d drop from the jug after the first fifty feet and not bother with the roped finish. As become his custom during our visit, Fred warms up by climbing a solid section of the route on his first go. I want to feel every hold on this route myself, so I begin at the back of the cave and work my way out, trying moves that look possible but mostly looking for evidence of chipping. The climbing is every bit as impressive as the grade indicates it should be. But 5.15b? Who knows? It’s continuous, dynamic, and very cool. Finally, on the last move before the section where Rouhling was handed the rope, I find a hold that looks as though it might be chipped. Rouhling inspects the hold I have pointed out. It is hard to tell if it is actually chipped or just a funky feature with lots of chalk on it. He says that he doesn’t think it was there when he climbed the route. At this point I have lost the cynical desire to catch Rouhling lying. But to be sure, I ask him to climb this section of the route. As Rouhling puts his shoes on, Tim and I exchange a glance. We’re going to find out what he can do, one way or the other. Rouhling steps onto the rock, and without so much as a grunt or a deep breath he fires the last fifteen feet of the roof without using the chipped hold and without any of the ticked footholds. He dangles from the horizontal, we stack pads, and he jumps down. This was the last question I had for Rouhling. I can’t think of any further ways to test him. By the time we finish our session, Tim and I are convinced that in his present state of fitness, Rouhling could climb Akira as it now stands. When I ask him why he has not been able to climb a route this hard in the eight years since his first ascent, he holds up three fingers. “Three things,” he says. “Route, style, and time. It is very hard to find a route which is exactly at your limit, and is exactly in your style, and you have unlimited time to try it. I have never found another one.” Two days after leaving Angouleme, Tim and I are sitting across the table from Alexander Huber discussing grading claims. When Huber speaks, there is weight in his words. Discussing another controversial climb, Huber asserts his reasons for thinking it is very unlikely that Bernabe Fernandez climbed his proposed 9b+ route Chilam Balam in Spain. I then ask Huber what he thinks of Fred Rouhling. Huber raises his gaze and looks directly into my eyes. His glare is so intense that I instantly understand how he is able to climb the hard, scary routes for which he is famous. “You should ask Dani Andrada about Fred Rouhling,” he replies. I ask him why I should talk to Dani Andrada. “Dani says that the route now is harder than when Fred did it. He says that there is Sika, glue, in the holds now. No? He says that Fred made it this way.” This description matched what I had found online. I say that I had heard the same thing, but that just two days ago Tim and I have seen Rouhling climb big enough sections of Akira that we are convinced that he has climbed the route as it stands now. Huber shrugs his shoulders and sips his beer. It looks like I have been dismissed. But Tim, who has done a bit of hard, scary climbing himself, is starting to get that look in his eye. Huber continues, contending that if a person has climbed at the cutting edge, there must then be a track record of his other hard ascents. Huber gestures with his hand: “If Rouhling’s level is here,” he says, holding his hand at chest level, “and then with Akira it is here” — he holds his hand at his forehead — “then there should be many other routes around here.” The hand is level with his nose. “Where is this track record?” Huber asks. The hand moves to the side of his head, palm up. “Why hasn’t he done many other hard routes soon after Akira?” Tim leans into the table and says, “Because he couldn’t climb for almost two years.” “Why is this?” Huber asks. “Because he had two kids, and his wife had brain surgery and almost died.” “Still,” Huber says, “there should be other routes.” On the drive back to Spain, Tim and I ponder the events of the last four days. The grade of Akira suggests that it should be compared to Chris Sharma’s Realization, but that’s the last thing that comes to mind when you look at the route. Rouhling himself is taken aback by the comparison. He says that at the highest level it’s impossible to compare two routes of such dramatically different styles. Rouhling says that for him Realization is the most impressive route in the world. He says that he would love to be able to climb it, but that he got shut down cold when he went there. (In fact, his account of the attempt is almost word for word the same as we had heard from Dave Graham.) Tim suggests that rather than calling Akira the world’s first 5.15b route, it might be better to call it the world’s first V15 or V16 boulder problem. Rouhling has demonstrated his ability to do V14 power routes and V15 traverses with little difficulty, so comparing Akira with those climbs might help establish Rouhling’s missing “track record.”

Fred Rouhling

Rouhling is now thirty-three years old. He and his family live in a fixer-upper house that they recently bought in the French Alps. It is well within striking distance of his new favorite bouldering spot, the granite blocks of Switzerland. Rouhling’s first goal is to avenge his near miss on Fred Nicole’s V15 boulder problem Dreamtime, which he climbed to the second-to-last move in 2003. His second goal is to climb the most famous of all hard routes, the late Wolfgang Güllich’s Action Direct in the Frankenjura of Germany. It is a power problem on pockets, very much in Rouhling’s style.Even if Rouhling does either route, it will likely not change the minds of his critics. But Rouhling listens to his children, not his critics. Of course, the children have no idea what 5.15b means, but they think Fred Rouhling is the greatest climber in the world.