Rick Ridgeway, Early K2 Ascensionist, Recalls Moment He Thought It Was All Over

Rick Ridgeway, on the summit of K2, part of the first American ascent, 1978. (Photo: John Roskelley)

Rick Ridgeway has lived a full life of adventures, and this is the long view of it—one that was almost shortened. One day six years ago on Lago General Carrera in the Patagonian region of Chile, he thought it had all come to an end.

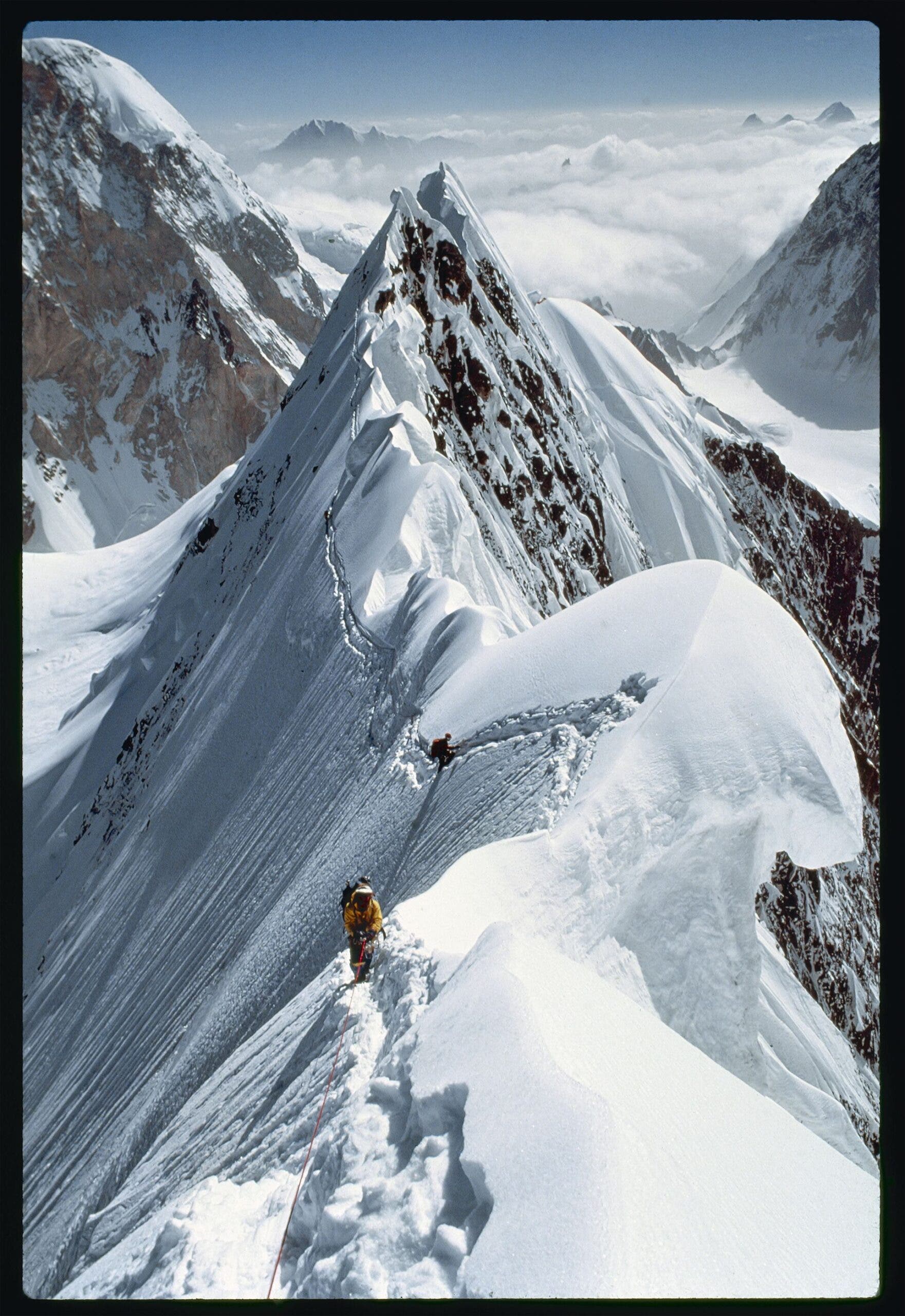

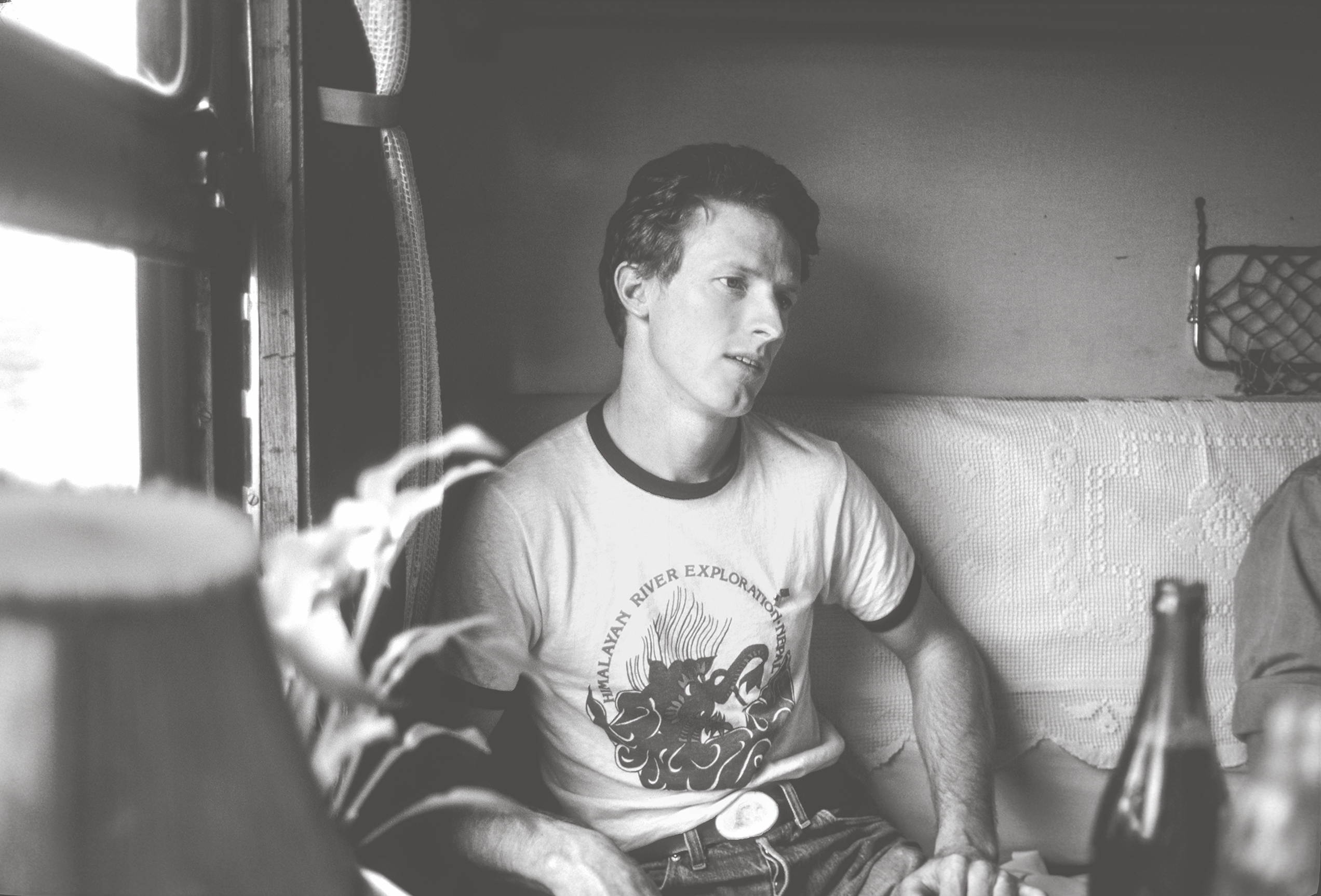

This excerpt is from Chapter 24, “That Unmarked Day on Your Calender,” in Ridgeway’s new memoir, Life Lived Wild / Adventures at the Edge of the Map. Ridgeway, with his lifelong friend and fellow environmentalist Yvon Chouinard, had survived an avalanche, the one he refers to below, on Minya Konka, Tibet, that took the life of his dear pal Jonathan Wright, in 1980; he had been one of four summitters on the first American ascent of K2, 1978; he’d led a trip that crossed Borneo coast to coast, walked 300 miles over the Tibetan Plateau, and gone to the deep Amazon to climb a tepui. This was not to be his last day, though it was for Doug Tompkins, co founder of Esprit and the North Face, a lifetime climber-paddler-skier and prominent conservationist.

Ridgeway has been known for his very candid and lucid prose since authoring the classic The Last Step: The American Ascent of K2, published in 1980 and detailing a great mountaineering story and the survival of Jim Wickwire in an open bivy just below the summit in -40 temperatures, but also the intense and divisive dynamics of a group of hard-charging people spending nearly 70 days together high on a remote mountain. Louis Reichardt and John Roskelley, as well as Wickwire, were the other summiters, with Jim Whittaker as leader. Chouinard wrote the foreword to the book.

Previous to Life Lived Wild, Ridgeway has written five books, including the memoir Below Another Sky: A Mountain Adventure in Search of a Lost Father, and co-written another, Seven Summits (with Dick Bass, then the oldest person to climb Everest, and Frank Wells). His books are known as much for careful and affectionate portraits as for recounting arduous effort and exploration. He also mourns a falling out.

The below excerpt is from his latest book, giving a story he had not yet told, about a dreadful day in 2015 with his close mountaineering friends. The book also recalls meeting his wife, Jennifer (Fleming) Ridgeway, like him a key figure at Patagonia, Inc. Jennifer completely changed the model of outdoor catalogs in introducing large-format, artistic photos of products, often worn and torn, in (hard) use, and upon her death at age 69 to cancer in 2019 she was mourned throughout the climbing and outdoor community. Who could ever resist her account of first going to visit Rick in Ventura, wondering if this romance—they’d met by merest chance in Kathmandu—was quite for real? An elegant model type, Jennifer was met at the airport by a grinning Ridgeway, Chouinard, and the Japanese mountaineer Naoe Sakashita, all compact in stature and, on that day, all partying. “Great,” she was to writer later in the catalog. “I’m being hosted by three drunk dwarves.”

Ridgeway’s is a tale of life with its ebbs and flows, of trips with many leading climbers from over the decades—from Roskelley to John Long and Jim Bridwell; Reichardt to Todd Skinner, Paul Piana (we can’t possibly help noting that in the Amazon, Piana was bitten by a piranha) and Monique Dalmasso (France); Dr. Chris Chandler to Jimmy Chin and Conrad Anker—and trips from which some did not return; of work, of meeting his life partner, raising a family (he and Jennifer had two daughters and a son: Carissa, Cameron and Connor), going in and out of expedition life; of filmmaking and conservation projects.

It is one of close companions—Rowell, Chandler, Schmitz, Wells, Bass, Bridwell, Skinner, Tompkins—lost, to natural and other causes. And of the many friends—Chouinard, Roskelley, such so-called “adopted children” as Jimmy Chin and Asia Wright (daughter of Jonathan Wright), and more—still deeply valued, who have come through for him.

—Alison Osius

The excerpt, about one of his many trips with his climbing and mountain partners Chouinard, Tompkins, and others from over generations:

Through the gemstone blue I could see from my position, upside-down and underwater, that the surface was just out of reach. My first thought was that I had to pull loose my spray skirt. But the weight of my body was enough to free the skirt, and in a second, aided by my life jacket, I was on the surface, one hand on my paddle and the other on our turn-turtled boat. Doug surfaced, and somehow he still had his white cap on his head. We looked at each other, and I could see in the set of his eyes that he had the same thought I did: in a matter of seconds everything had changed, and now we would be fighting to stay alive.

“Let’s turn the boat over,” Doug yelled.

I moved to the bow, and on a one-two-three we flipped it upright. We worked our way back to our respective cockpits. A yellow dry bag that held my journal was floating near the boat, so I retrieved it and threw it in the cockpit. We were on opposite sides of the boat, and on another one-two-three we pulled ourselves back up on top of the boat.

“Now try to straddle,” Doug yelled.

We both sat up, straddling the boat. We still had our paddles, and, struggling to maintain balance, we started to dig our paddles into the water. With the wind fully on my torso, I felt the cold even more than when I had been in the water. In only two more seconds, another wave hit and again the boat turned over.

“Let’s try it again,” I yelled.

Once more we flipped the boat, crawled on top, and sat up—only to be knocked over again. It seemed like our only option, so we tried it again, and again the waves knocked us over.

“The wind is taking us away from the point,” I said. Doug didn’t answer—there was nothing to say. Our situation seemed not just grim but near hopeless. Even though the profile of the upturned kayak was not that far above the water, it was exposed to the wind enough that it was propelling us even faster toward the center of the lake than the current alone. The point was still close—maybe a couple hundred yards—but we were quickly being carried away from it.

“Maybe we could swim?” I yelled.

“You think?”

“I don’t know. We’re being pushed out fast.”

“Any sign of those guys?”

“No. They might have kept going.”

We held onto the boat. We had been in the water for a few minutes. How much longer did we have? Fifteen minutes? Twenty? A few yards away I could see the dry bag with my journal, the journal I would add, when the year ended, to the shelf of journals I had kept since I was twenty-five years old. But it was too far to retrieve. Would anyone ever find it? Would anyone ever read the entry I made last night, about the beautiful sunset?

“Maybe we should try and swim,” Doug said.

“That might be our only chance.”

We both let go of the boat. I started to stroke, but it was difficult with my life jacket. I turned over and backstroked. That worked better, although the waves kept washing over my face. I stopped to catch my breath and saw Doug on his back trying to use his paddle to backstroke. Maybe I should have kept my paddle? I looked around but couldn’t see it.

Concentrate on swimming. Backstroke is best. Kick, pull with my arms. Another wave, close my mouth. OK, now swim, hard. Another wave . . .

I hadn’t closed my mouth in time, and I coughed to force the water out of my throat. When I caught my breath, I decided to try the breaststroke again, but it was difficult with the life jacket.

The life jacket. Why isn’t it working? Shouldn’t it be keeping my head higher? Try holding my breath and stroke with my face in the water. Two strokes, three. Up for a breath. Back down. Two strokes, three. Up, breathe.

But a wave hit just as I lifted my head, and again I breathed in water and had to cough it out. I looked for Doug. He was farther away, and he no longer had his paddle. Maybe the idea hadn’t worked? That was just like Doug, trying to use his paddle as though his body were a boat. Always thinking, always trying something new.

Backstroke. Pull with my arms. Kick. Kick. Wave. Close my mouth. Breathe. Kick, stroke.

Another wave washed over me, and again I had to cough out water. I looked toward the point. It was about the same distance, no farther but no closer. We were holding our own, but that wouldn’t be enough. We had to swim harder. I returned to the backstroke, but each time I came up to breathe the waves washed over me and I had to cough out water. I couldn’t see Doug anymore. I looked at the point, and there were people standing on it. Two, maybe three. Jib, Lorenzo, Weston, Yvon. Did they see us? I waved but they didn’t wave back. I yelled, but then realized with the distance and the wind that yelling was futile.

I waved again, but again no one waved back. Then they disappeared. Had they seen us?

Maybe they saw us. But have to keep swimming, have to get close to the point. Backstroke is better. Stroke, stroke, wave, close my mouth, stroke, stroke, wave. . .

I stopped to cough out water. The life jacket didn’t seem to be working. I was starting to drown. The point was there, still the same distance. How much longer did I have? Ten minutes? I rested my head against the life jacket and looked across the lake to the peaks, white snow against cerulean sky. So, this was the day. December 8, 2015. The day on the calendar, the day that had always been on the calendar. Always unmarked, until now.

I looked around. The peaks were so beautiful. And this time, unlike the avalanche, when everything was whirring by, this time I could pause and enjoy the beauty. This time, it was peaceful. I turned over, face in the water, eyes open. The gem-stone blue. Fathomless. The blue world. The blue beauty of the blue world.

Get my face out of the water! What am I doing? Giving up? I never give up.

I yelled as loud as I could, No! And again, No! The yelling forced the water from my throat and made it easier to breathe. With everything I could muster I yelled No!

Then I turned and swam. I made two strokes, three, then stopped to catch my breath and stroked again. Whenever I swallowed water, I yelled No! and that cleared my throat. I wouldn’t stop swimming until my body couldn’t swim any longer.

Then I saw them, my friends, in their boats. Two boats coming toward us. I stopped and waved and saw one of the boats turn toward me. Our friends were coming to rescue us. We were going to make it! We were going to live!

As the one boat got closer, I could see it was Jib [Ellison] and Lorenzo [Alvarez] in the double kayak. In another minute they were alongside me.

“We can’t carry you on top,” Jib said. “Hang onto the back loop.”

I grabbed the rope loop on the stern of the boat with my right hand and felt the water move by me as Jib and Lorenzo started paddling toward the point. I closed my eyes and focused on my hand, on keeping my grip on the loop.

“You OK?” Jib yelled.

“Yes. What about Doug?”

“Weston has him.”

Weston has Doug, I thought. All we have to do is hang on and we’ll get out of this alive.

Keep your grip. Fingers folded, tight. It’s taking so long. We must be there by now?

I opened my eyes and saw the shoreline. I picked a rock and focused on it. We were moving past it, but very slowly. I closed my eyes again so I could focus on my grip.

It’s taking so long. But I’m still OK, even kind of comfortable. Is that Jib calling to me? Don’t try to answer, just focus on your grip. It’s taking so long.

I have a vague memory of rocks under me, and then being pulled over rocks. Or was I trying to walk? I’m not sure, but the next clear memory was both what I saw and what I felt. It was fire. Fire burning in front of me. Fire, and the feeling of warmth on my face.

* * *

“Are you OK, Rick?”

It was Jib’s voice. I was in a sleeping bag and he was in it with me, holding me against his body. I shivered violently, my body convulsing.

“Yeah. Where are the others?”

“Yvon’s down the beach, but close. He’s OK. We called a helicopter, with the sat phone. It’s here and it picked up Lorenzo, to go find Weston and Doug.”

Sadly, Ridgeway’s relief was not to last, though the young Weston Boyles (also a climber-paddler) made sustained heroic efforts and risked his own safety to bring Tompkins to shore.

Life Lived Wild: Adventures at the Edge of the Map goes on sale Oct 26, 2021, hardcover by Patagonia Books, $30.

Audiobook available through Penguin Random House.