Sard in a Can: Part I

"None"

3/08/08 For the next month Climbing.com contributor Bruce Willey and his wife Caroline Schaumann will be sending dispatches from Sardiniaan Online exclusive. This is their story: A story of average climbers, with average means on an average quest to explore the uncommon island off the coast of Italy.

Dispatches from the Island of SardiniaOverlooking the orange groves and pastures just outside Quirra it becomes clear: we sound like sheep. The quick draws tinkle like the sheep bells, and after a week of climbing we begin to feel as though we are blending into the Mediterranean landscape. Each day has brought a new crag of limestone to explore. And here on the island of Sardinia, or Sarda as it’s called, the days pass gently into the next, making time answer to a sublime old-world version itself.

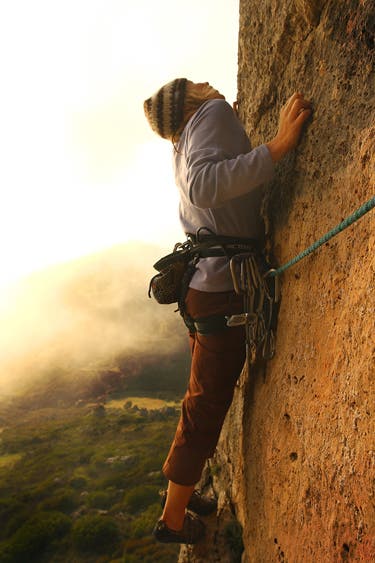

Yet despite my wistful slide into the pastoral when I manage to find a good stance and look around, I have to admit this (6a/b or 5.9/5.10) climb Spit’s Family in the Sárrabus region of southern Sardegna has me plenty gripped. And what exactly is a 6a/b anyway? The ratings here are often lost in translation. Furthermore, just as I’m about to clip the last bolt before the anchor and reel up some rope, a large white owl flies out of its nesting hole at my head, glances my shoulder and neck with a wing and shits on my pants. I nearly do the same.

In a split second before the owl had made its escape, I’d registered two large yellow eyes peering at me. It just didn’t seem possible that I’d be sharing the crux with a large bird. So I must have written that possibility off. In Sardegna it’s easy to fall into bucolic complacency. On the one hand Sardegna seems tamed by the thousands of years of civilization. In fact, above this one crag there’s a Neolithic tower and at the base an archeological dig in progress. Moving further out in the historical continuum, the Carthagians, Romans, Egyptians, Spaniards, Moors all settled, pillaged, or occupied the place.

And then there are the plants and trees that make it entirely too easy to draw comparisons to California from where I hail. Palm, olive, eucalyptus, fig, and oak trees cloak the landscape or take it over all together. The weeds look the same too. And the plants that Californians buy in the nursery grow wildrosemary, eccium, narcissus. Prickly pear cactus grows in the lower elevations of the coast, and in the fields and orchards the farmers grow lettuce, artichokes, strawberries, and oranges. It’s California before urban sprawl, before the population boom, before freeways. A California that I only got a brief glimpse of when I was a child growing up in San Bernardino before developers chopped all the orange trees down to make homes and large box stores.

But on the other hand, as my encounter with the owls attests, Sardegna feels very much wild. In four days of climbing we have not run into a single climber. We have seen far more sheep than people. And the crags are usually a long dirt road away from small towns perched on steep mountainsides. Narrow towns where pious old women in black make their way to daily Mass and old men sit on the side of street, smoking and talking for a thousand years.

We had come to Sardegna in late February to escape what seemed like a perpetual winter in Berlin. We still climbed in Berlinon old World War II bunkers or at the overly expensive gymbut the cement began to eat at our skin, the cold shriveled our desire, the plastic pulls just a workout. So, for an 18 Euro fare on Easy Jet, we flew south for a week. While sipping a mid-day cappuccino in the sun on our first day here after a hard morning of climbing in Jerzu we knew it would be difficult to leave. By the third day we knew we would be back.

Originally, the plan was to leave Europe after Sardinia and live in Moab, Utah for a month before settling down for a long spring and summer in Bishop, California where we rent a small cottage each summer. But going over the logistics we realized it would be almost cheaper to trade Utah for Sarda.

All of which warrants an apology for those with real 9-5 jobs. In spite of the appearance of being jet set dirt-bags, we are neither. Thanks to my wife’s academic position in Atlanta at the same school “Alexander Supertramp” of Into the Wild fame attended we’ve managed to eke out a living mostly where there is good climbing during her sabbaticals. My freelance writing career is so unprofitable that it doesn’t matter where we live.

Aside from two semesters spent in the shallow end of the Deep South we have nearly complete freedom to go anywhere as long as we can still get some work done. Of course the flat cornfields of Kansas would be ideal for such concentration. But Caroline swears she gets more done if she can climb nearly every day. And I’m certainly not going to argue with her.

Local Italians come to see the climbing near Jerzu. Photos by Bruce Willey www.brucewilley.com

And so two years later we’re in the Ogliastra region of Sardegna, renting a small flat from some British ex-pats whom we’ve yet to meet. Sometimes life can become a stretch of the imagination even when you’re living it. Today drove that point home. We were climbing the Ìsola del Tesoro outside of Jerzu. The crags look almost as if they plopped down from Indian Creekif Utah were so green. We started to the right with some 5b/c warm-ups (Stregatto and Topo Gigio) before Caroline redpointed and nice little 6a+ (Tempo Da Lupi). The sun was an hour from going down and we were trying to put in a few more routes before dark. A gaggle of teenagers came up through the bushes, their Italian sounding to my mono-lingual ears like little songs. They stopped just as I was grunting over a roofy move and said Buóna séra.

They hung out for a while watching us and laughing. When I got down they asked in what little English they knew where we were from, where we were staying. They were kind and gentle, almost like one would imagine teenagers from the 50’s. Slightly dorky, but cool nonetheless, and without an ounce of pretense or angst. We hung out for a while and I tried to tell them how beautiful their country was to no avail. They just shrugged, and the girl in the group started singing the words to a pop song in English.

And after a long day of climbing… Photos by Bruce Willey www.brucewilley.com

In the guidebook to Sardegna (Pietra di Luna) by Maurizio Oviglia, he describes the Lìsola as “the best wall in the world.” As we climb more and more areas this week we have begun to see a pattern in the guidebook. Nearly every area that Oviglia describes in rich, enthusiastic detail, he most always concludes that each crag or climbing area is “the best in the world.” But who can complain. He’s probably right. But for Lìsola he does manage to qualify it with, “Best wall in the world especially when at sunset the rocks become golden…one never wants to leave it.”

Indeed: the only way we could think of leaving was to remind ourselves of the prospect of a warm pizza and a bottle of Cannonau wine, (more wine and more on this later, but Cannonau is the mother of all wines), back at the apartment. That, and of course the assurance that we will be back.