Sard in a Can: Part II

"None"

3/17/08 For the next month Climbing.com contributor Bruce Willey and his wife Caroline Schaumann will be sending dispatches from Sardiniaan Online exclusive. This is their story: A story of average climbers, with average means on an average quest to explore the uncommon island off the coast of Italy.

Dispatches from the Island of Sardinia

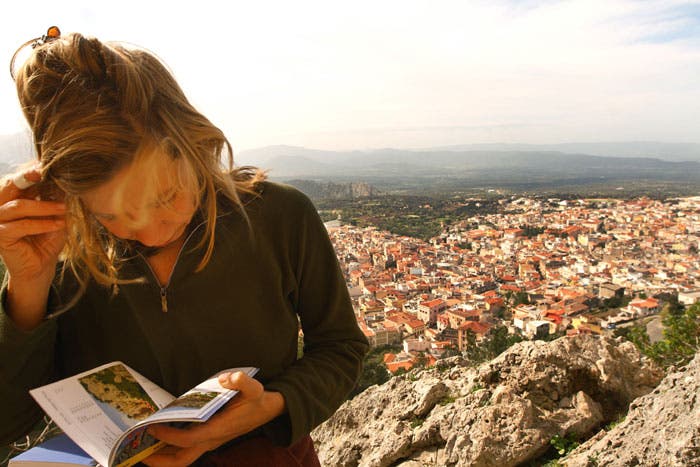

Every time I turn around I catch the missus reading the Sardegna guidebook. Later in bed, she marks off climbs we have done today, highlighting climbs we are going to do tomorrow, and climbs we will never get around to doing. There’s simply too much rock in the world. But she tries. I suppose if you hang around on million year-old rocks long enough it’s easy to forget that a human life is so short in comparison to geologic time as to barely register at all.

Yet climbing in a foreign country is travel with a purpose. You miss out on a lot of museums, churches, cafes, shopping, sightseeing trips, and luxurious hotels when you climbjust like the locals. But having a purpose lets you experience the country more closely. And a purpose gets you off the beaten track, far and away from the tourist traps in the first place. You begin to see the world around you with renewed freshness. Grocery stores are a great place to start.

We were totally bushed after climbing all morning at the Villaggio Gallico crags, then a long hike down to Cala Goloritzè in the afternoon with a few pitches up the Aguglia before sunset forced us back up the trail. After nearly hitting a cow and a herd of goats on the small one lane road over the Golgo Plain, my attention began to wander to thoughts of an Ichnusa (the Sard beer) and some gulurgiones (a ravioli filled with potatos). We got on the main road and began our approach into the town of Baunèi when we saw a group of huge prickly pear cactus walking on the side of the road. It had been a long day, but I didn’t think it had been that long. Slowing to nearly a stop to allow them to pass, we realized they were merely cactus costumes. Kids these days, I swear.

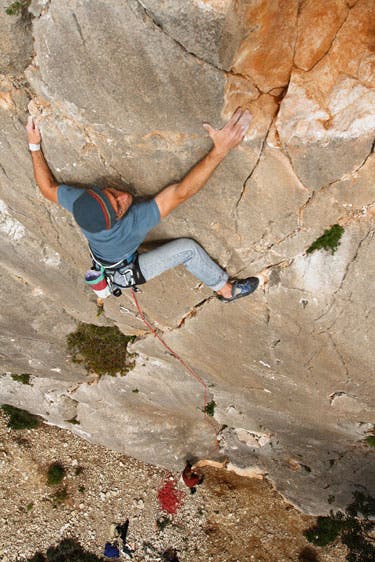

Animated cactus or not, Sardegna often feels like a dream state. And no place is more dreamy than the Aguglia of Cala Goloritzè. Rising 800-plus-feet out of the turquoise sea below, the Aguglia looks like it belongs in Patagonia. It’s difficult to describe without falling into a hackneyed brand of magic realism. Climbing journalist and Sard guidebook author Maurizio Oviglia does his best, but even he concedes that words fail.

“When talking of Cala Goloritzè,” he writes in Pietra di Luna, “the superlatives used to describe it are never sufficient. I have never come across a place as wild and beautiful, where the rock, perfect in every aspect, merges so marvelously with the deep blue of the sea and the green of the juniper. However it would be wrong to describe this place as the best of the best, even if classifications are the only means of comparison nowadays. Instead I would say that the Aguglia provides an emotion of its own, something that is different from what one experiences on a crag, something that is neither alpinism nor climbing, but that one must try.”

Well, we tried. We went up a pitch or two of Sole Incantore (6c), looked at the setting sun, looked up at the hard pitches above, and rapped off prudently. The easiest route up is a 6c, perhaps over our heads if we had all day. But we felt the emotion and like Maurizio we concurred that the Aguglia was yet another place that was the best in the world. And we’ll be back to finish it for sure.

For the last two weeks, we’ve stayed at Peter and Anne’s flat in Arbatax in the Olgiastra region. Today we finally got a chance to meet them. They were away in Australia visiting “mates” when we first arrived. Peter is a longtime climber from the Peak District of England and now divides his time road biking the smooth, steep, curvy Sardegnian roads with climbing the limestone any chance he gets. Anne hails from Scotland and has the accent and wry humor to prove it. She climbs too, but trends towards long treks in the mountains. After years in the corporate world, they shucked their careers and moved to Sardegna where they own and operate a bed and breakfast in Lotzorai called the Lemon House (www.peteranne.it), a ten minute drive from where we are living.

We ring the doorbell at the Lemon House, which is indeed the color of its namesake saving it from overstated British whimsy. The neighbor’s limping pregnant cat (it was knocked up, then hit by a Fiatapparently) meows at our feet. Anne answers the door. She is short with thick-rimmed glasses, but her total impact makes her appear much taller than she is. She doesn’t suffer fools easily.

Anne gives us the tour of the three-story house where they live and entertain guests from all over the worldmostly climbers, cyclists, trekkers, and the odd bits and ends that end up in Sarda. We end up on the roof ourselves, overlooking Lotzorai, the Med, the hills and mountains beyond. From this vantage point can see that they are somewhat visionary for picking the location: Tapped and untapped crags can be seen for miles. It is possible that the Ogliastra region is set to be the next big climbing destination after the more famous, well-established areas like Cala Ganone to the north and the steep overhanging crags of Isili to the west.

From our home base in the Ogliastra region we have been able to branch out in all directions, albeit within the limits of my old lady Italian driving skills. We have climbed nearly every day save for the one sunny day when I put my foot down and went to the beach to write a letter and the first Sard dispatch. We have become hopelessly enthralled with the landscape, the people, the food, the limestone. The apparent simplicity of living within the Mediterranean brightness warms our skin, turning the long winter into the first day of summer. But of course all is not so simple. In many respects, this is a poor island. Many people are forced into leaving the island to find work elsewhere in Europe. And the tourist trade, such as it is, is seasonal and pays hardly a working wage.

Then, from our roof top position we spot a white Fiat. It’s Peter. We file down the winding staircase to meet him. On the way out the door into the sun by the sleeping pregnant three-legged cat, I close the front door to the Lemon House just as Anne says, “no need to bother closing the door.”

Too late for that…

Peter gets out of the Fiat and hobbles painfully across the street. Between now and their trip to Australia he spent some time with Maurizio, climbing British gritstone. The limp is thanks to a 15-foot fall. His ankle is swollen blue, sticking over the top of his shoe. He’s in a foul mood.

We’re locked, or more precisely, they are locked out of their own lemon-colored house thanks to me. A neighbor walks and they talk to him in Italian, figuring out what to do short of calling the locksmith. A plan is hatched after we spot a metal ladder leading on top of neighbors house. Problem is, there is an angry German Shepard with one floppy ear guarding the yard below. Peter distracts it, and I climb over the stone fence. Then I drag the ladder on top of the other house and prop it up to the Lemon House.

“Oh and you thought you’d be climbing rocks today, and now you’re climbing houses,” Anne says to Caroline, while they watch from below.

I gain entrance through the roof and open the door below. Then climb back up and lower the ladder to where it was above the still pissed-off dog. The piece of twine holding the ladder is so sun burnt it falls to pieces in my hand. Sadly, it is probably the most heroic bit of climbing I’ve yet done in Sardegna.

Despite Peter’s foot, he asks if he can catch a ride with us to the crags. Anne makes us promise we won’t make him climb too hard. So we venture up into the Campo dei Miracolo and the Ichnusa area overlooking Pedra Longa and the sea. It’s a beautiful spot, obviously, made more beautiful by the pigs we have come to know from coming here over last two weeks, and I suppose, named in part after the refreshingly good beer, which is in turn comes from the Greek word for foot. How the ancient sailors knew that from the coastline navigation alone is something we’ll probably never understand. But all this hardly matters as we spent a few hours together, goat bells ringing on the hillside above, the occasional fine snort of pig, the broad ocean below, and one move after another on another fine piece of limestone crag hanging there for no other reason or purpose than to climb somehow.