Special Report: Libecki Brothers Explore Vertical Greenland

"DCIM102GOPRO"

After three weeks in Africa with my daughter (where she completed her personal goals of climbing Kilimanjaro and visiting all seven continents), I had only four days at home to de–jet lag, unpack and repack, and get on a plane headed east toward Greenland. First I made a pit stop in Chicago for a three-night mini-expedition to the Grateful Dead’s “Fare Thee Well” concerts. I rocked out hard—it really was like training for the big challenges that awaited.

At this same time, my climbing partner—my brother Andy—was flying from California to meet me in Iceland, where we would board another plane to Greenland. Originally, I had planned this trip with Ethan Pringle, but circumstances led him to back out. I re-routed my psyche for a solo expedition. Then, out of the blue, just a week before leaving for Greenland, my brother said, “Hey, could I go?” Andy had done two previous climbs in his life. Both were first ascents, one in China and one in Kyrgyzstan, both with me. I said to him, “Dude, yes, let’s do this!”

We lost a few days because of flight cancelations and missing bags, but finally we boarded a flight to Tasiilaq on Greenland’s east coast. I had flown this same route seven times since 1998, and I had never seen so much sea ice clogging the coast. It was like a million-piece puzzle of white geometric shapes. Once we landed in Greenland, we were planning to travel nearly 400 miles by boat through this maze of sea ice. Our goal was a remote fjord that I had reconnoitered the previous year with Andy Mann, but had to failed to reach on three prior expeditions.

Our boat captain was Siggi Sigurdsson, the most experienced in the area, at the helm of one of the most Arctic-ready boats around. But Siggi had gotten stuck in sea ice while navigating his 40-foot boat back to Tasiilaq from Iceland. With his wife and kids on board, Siggi spent more than a week trying to find a passage. No one had heard from him for several days when we got to Greenland. The next day Siggi finally contacted the local authorities and said he would find a way through if it took him two weeks. Five days went by, and Siggi still battled the sea ice. Then we got an update: Siggi’s boat was taking on water and a rescue had been called in. A helicopter hoisted Siggi and his family to safety, and his boat was left to drift and eventually sank. Fortunately everyone was safe.

How would we make it to the walls I have obsessed over for a decade? My friend Hans Christian sent word around Tasiilaq that I was looking for another boat. In fact we would need two boats in order to carry enough fuel for the round trip in addition to all our gear. Finally we met Bendt Josvassen and his wife, who was willing to attempt the journey with some friends who would drive the second boat. Soon, we watched the blue, green, yellow, and red houses of Tasiilaq disappear as we entered a maze of sea ice and icebergs. Optimism raced through my veins. Mystery was lurking. The two weeks of delay didn’t matter now, except now we had only about two weeks left to complete the expedition. Continuous mental chanting: Keep moving forward.

We expected it to take about 45 hours to reach our destination. Bendt, his wife, his 13-year-old son, his 19-year-old daughter, and their lazy cat all joined us on his boat. We never stopped moving; one person slept while the other drove. We slowly navigated through icebergs in an electric-blue sea. The beauty was hypnotizing, and Andy and I could barely sleep, not wanting to miss one second of the scenery.

Ice maps showed a very thin channel of open water through which we hoped to sneak into the larger part of the fjord where we hoped to climb. But when we got there the channel was jammed with ice. Smiling all the time, Bendt steered his boat back and forth, investigating the ice, for about 20 minutes. Then he slowly approached a section of ice and pushed the bow up onto it. The engine was racing, pushing and pushing, and all of a sudden the ice started to move, shifting and rotating and crashing into the sea. Next thing I knew, we were through the blockade of ice and slowing maneuvering deeper into the fjord.

I knew exactly where I wanted to go. I had satellite images from the Danish government and every map ever made of this area. I knew the Polar Bear Fang Tower was just around the corner. It was close to 1 a.m. and the sun was hiding behind the massive mountains that surrounded us. Before landing, Bendt sailed back and forth to look for polar bears. Last time I was here, there were 11 bears in the area.

Andy and I grabbed some bivy gear and fourth-classed to a ledge high on the cliffs near shore, safely away from bears. The next morning we set up a deluxe basecamp and then started carrying loads up the long valley toward the elusive tower, shotgun over my shoulder and flares and pepper spray in our pockets.

We hiked for a few hours up a talus ridge, and eventually came to the first of several glaciers we would have to cross. Big, deep crevasses were evident. I showed my brother everything I could about this terrain and the techniques required, then armed him with ice axes and rescue gear, harnessed up, tied in, and we continued shuttling loads.

My brother doesn’t have much experience on super-technical mountain terrain. He was learning—or relearning—as we went. I knew from past experience that Andy had the focus, determination, and communication skills to do what needed to be done. He had followed me up a big wall in the Tien Shan in China in 2005, and up a huge route on Asan in the Karavshin in Kyrgyzstan in 2006. We had fun. We laughed. It’s a beautiful thing sharing grand adventures as brothers. Joy on these trips is the most important fuel.

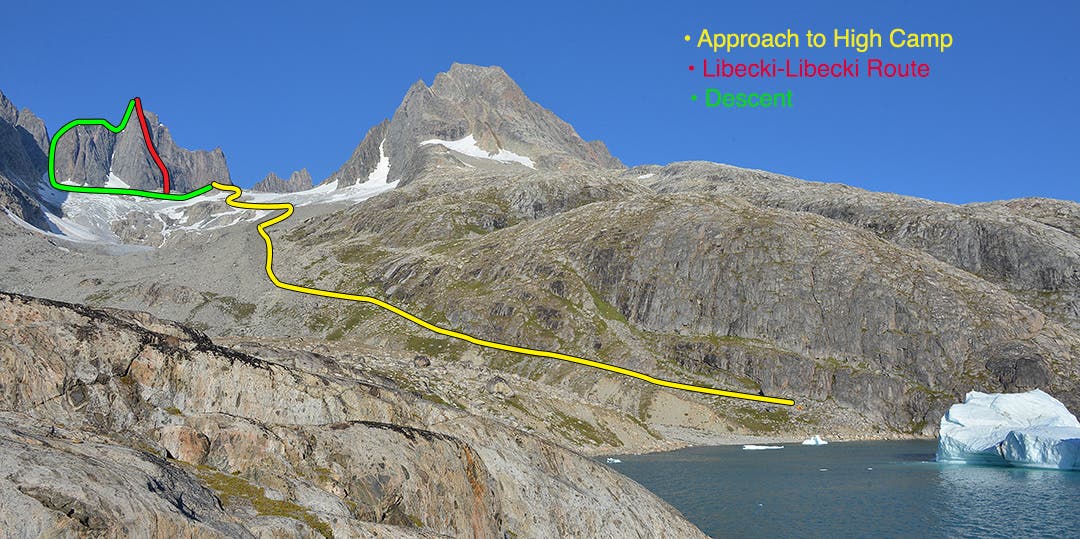

After a few days, a few dozen miles of hiking back and forth, and several roped-up glacier crossings, we came to a beautiful granite ridge surrounded by glaciers, about 900 meters above our seaside base camp. We had carried enough supplies to stay up at this high camp for at least 12 days.

There was no doubt in my mind that no human had been here before. No doubt that the Polar Bear Fang Tower was unclimbed. We stood less than a mile from the tower that I had been trying to get to for a decade—in a way, for my entire life.

A recon revealed a fairly simple scramble, with only one rappel, to reach the glacier between camp and the tower, and the glacier proved surprisingly easy to traverse. Finally we stood at the base. Most of the rock, at least down low, looked really loose, but after a few hours of scrambling and scoping, I could see a few possible routes. Once back at the high camp, I studied the tower with my 300mm lens. Honestly, this was no place for a beginner, let alone someone on his third climb ever. I was counting on the energy of our brotherhood to generate optimism and keep us safe. Brotherhood, blood, bond, belief. It started snowing and we took a couple of nice stormy rest days, ate a lot, and read our books.

Once the sun came back out and melted the snow, we racked up and headed to the base of the tower. I decided to bring the satellite phone—the first time I’d ever brought one on a climb. At least Andy would have some kind of fighting chance if something happened to me up there. We decided to start our push the following morning after a bivy at the base of the tower. I planned to free climb the entire route, while Andy would follow me on jumars. Before we got in our bivy sacks, I fixed a pitch and had him clean it for a quick refresher. He cleaned the pitch with ease.

We left our stove at high camp and took only Clif Bars, Shots, and Bloks, plus three liters of water. I led with two ropes and a double rack of cams and nuts, a few hexes, a hammer, six pitons, four bird beaks, and two alpine aiders. Andy would follow with the pack, food, bivy sacks, sat phone, Year of the Ram masks, approach shoes, a small bolt kit for emergencies, headlamps, rain jackets, and light down jackets. We both had a two-way radios clipped to our harnesses.

We started in light fog and clouds. By the third pitch, I’d already been forced off my planned route to avoid huge, hanging daggers of rock. We ended up veering way left, but the fun 5.10 pitches delighted me, with good pro and natural anchors at the end of 60-meter pitches. Considering my brother would be jugging on a rope amid lots of loose rock, with little experience, I really focused on how the rope would run, placing extra gear for directional so Andy wouldn’t pull loose rock on top of him as he jumared.

The almost-full moon came out just as the time for headlamps neared. The clouds were like gray, eerie paint strokes over the moon in a surreal painting. There was a ledge off to the right we could rap to, just big enough to sit on and get some sleep. As a bonus, we found water dripping into a hole in the rock about the size of a bathroom sink. We were able to sit next to each other and shiver out the night.

When the sun came back above the horizon, we got out of our frost-covered bivy sacks and filled our water bottles from the bathroom-sink hole, then washed down Double-Espresso Clif Shots and Clif Bars. We jugged back to the anchor, and Andy stacked ropes as I racked gear. So far, I had not encountered anything harder than 5.11 and all of my anchors were natural pro. It was a good style and we were having real fun, not just the it-doesn’t-have-to-be-fun-to-be-fun type. The next pitch had cool, flaky laybacks with short 5.11 cruxes and good rests every 10 to 15 feet. This is where my hammer and bird beaks were worth their weight. I placed all four of my large beaks on this pitch, but delicately so they could be cleaned without a hammer. We climbed all day until the sun went around the corner and shade trapped us in shiver-land.

I knew we were getting near the top, because we were above every other summit I could see. But the crux of the route came two pitches before the top: a huge chimney filled with loose flakes and rotten stone-teeth. When I finished the pitch, I radioed to Andy, “Hey man, belay is off, and please, please go really slow, be careful what you touch, focus man, no mistakes.” Just inches from my anchor were big teetering fingers of stone I did not want to touch, but Andy finessed through the minefield without a problem. Our reward was an overhanging bombay chimney on the next pitch—one of the coolest 5.8 pitches ever.

Often the last technical pitch below a summit can be the most dangerous in terms of loose rock. But on Polar Bear Fang, a full 60 meters of 5.9, clean granite took me to within 20 meters of the true summit. A walkable, knife-edge ridge led to the fang tip. To the west, I saw what looked like the mushroom cloud from a nuclear explosion—a storm system headed our way. Our summit celebration would have to wait.

After half an hour of work, we had crafted a small bivy, just 10 feet from the summit, coiled our ropes into mattresses, put everything on, and waited for the shiver fest. Then, as we watched, the storm slid past us, as if deciding we didn’t deserve such a fate. The dark pink-maroon horizon was stunning. It felt perfect in an imperfect world. A couple of hours later, we were shivering so uncontrollably that we could not stop laughing. We mocked Jack Frost. It was like we were kids again.

We never really slept, but eventually crawled out of our frozen bivy sacks when the sun returned. Now we finally celebrated the summit, donning our Year of the Ram masks for photos. On my watch the elevation read 2,030 meters, about 855 meters (2,800’) above the start of the climb. We were on the highest summit as far as we could see, nearly 400 miles from the nearest civilization. It was a glorious moment, not only because of the many years I’d spent trying to reach this exact moment and place, but also to be here with my brother. And to see my brother give everything he had to be here with me.

Now we faced a first descent—an entirely new challenge. I didn’t want to descend the route we’d climbed, with its friable rock. Instead, I decided we should rappel off the opposite side of the tower and try to reach a gully we could descend to the glacier, tiger-striped with crevasses. We started rappelling, like spiders on giant shards of stone, stacked like the crux of a Jenga game—the tiniest move and it all falls. My serious voice came out again, “We have to be really fucking careful, watch each move, watch everything you touch—this whole thing could go.” Andy knew all this already, but I had to communicate. After six rappels, we gained a ridge on the backside and traversed to a huge ice gully. With each pull of the ropes, loose rock followed. After seven more rappels down the gully, we had to Tarzan- swing over a huge moat to reach the glacier.

We had not carried crampons or ice axes, so I told Andy we’d cross the glacier like polar bears would. We stuffed gear into our bivy sacks and began crawling, equalizing our weight on hands and knees, and towing the sacks as sleds behind us. The full moon came out. My hands felt like claws; I felt like a wild beast. Andy and I crawled for half a mile to our high camp, laughing and laughing, just as we had our whole lives together.

The Libecki-Libecki Route on Polar Bear Fang Tower went in 16 pitches at 5.11. I want to give huge thanks to the sponsors of the Mugs Stump Award and the Shipton-Tilman Grant for making this trip possible.