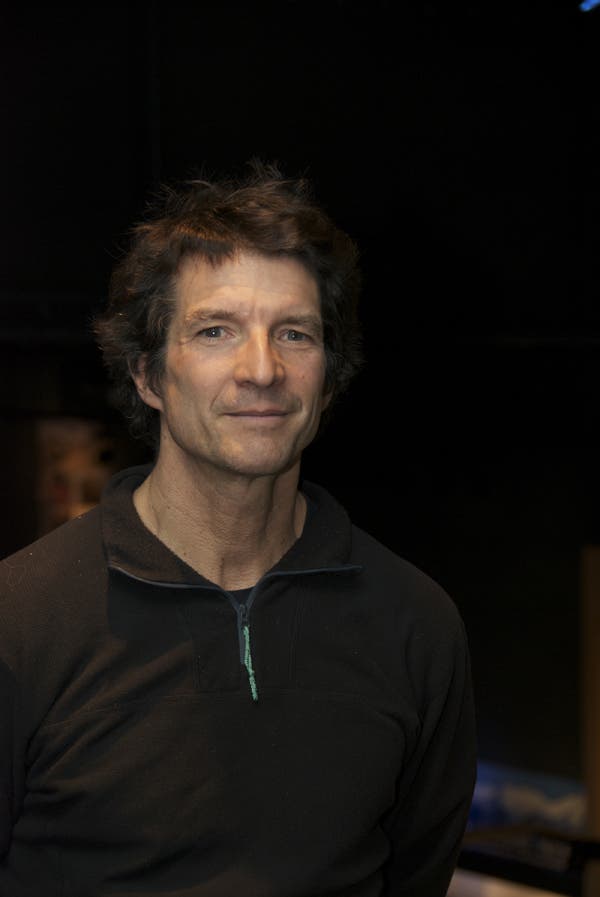

STEVE SWENSON

"None"

Alpinist, Engineer, Family Man, Free Spirit, President of the American Alpine Club; Seattle, Washington

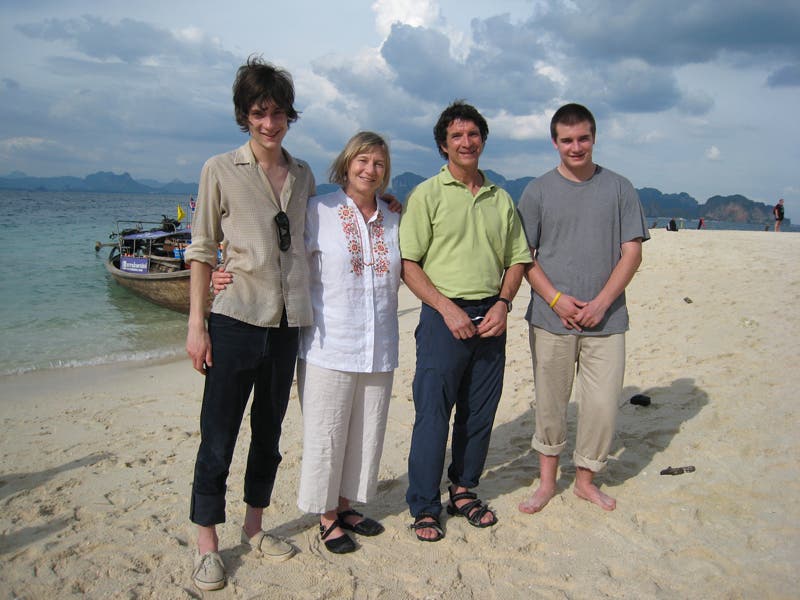

The Seattle native (born and raised) Steve Swenson, 55, is the quintessential Northwest hardman. His climbing career spans four decades and includes the second ascent of the North Face of Mount Alberta, in 1981; the FA of the Northeast Face of Kwangde Nup, in Nepal, in 1989; and the FA of the Mazeno Ridge on Nanga Parbat, in 2004. He’s also summitted K2 (1990, via the North Ridge) and Everest (solo, in 1994), both sans oxygen. Swenson’s select list of gnarly mountain bids occupies three pages of small, single-spaced type, all amassed while he worked 30-plus years as an engineer for R.W. Beck, Inc., of which he’s part owner, and raised two boys Lars, 28, and Jed, 18 with his wife, Anne. Swenson’s partners have included Doug Chabot, Colin Haley, Steve House, Alex Lowe,

George Lowe, and Mark Richey. In February, the American Alpine Club (AAC; americanalpineclub.org) appointed Swenson president following his three-year stint as vice president, under Jim Donini.

I was drawn to climbing in the third or fourth grade. My parents weren’t drawn to the outdoors they were very religious. To go out on the weekends and climb and not go to church was a big deal.

When I was in my 20s, there was no such thing as sponsored climbers. You had to make money; you had to support yourself. I do environmental water-resource engineering work water-quality and fish-habitat stuff.

My wife gets asked questions all the time, oftentimes by other women. They’ll say, “What do you think of Steve being gone all the time?” And I think she gets tired of that. Somebody asked her that question once and she just said, “Fish gotta swim, Steve’s gotta climb.”

When I climb with younger people, that’s because those are the people who’re still doing it. I’m on my third or fourth generation of climbing partners.

Back in the 1960s and into the ‘80s, there were fewer venues for people to spray. With all these forums and blogs and more magazines, there’re just so many more venues for people to talk about what they do. I don’t know if we were exceptionally stoic or reserved it’s just how things were at that time. My parents and my in-laws, when they came back from WWII, they had these horrific experiences and none of them said anything. People didn’t really go out and brag about all their little exploits.

I’ve learned a lot about climbing from people like Steve [House]. Like when we were in the Charakusa in 2004, I really upgraded all my gear. I had old hardshell stuff, with pile pants. They teased me about it. I had an older ice axe I’d brought that I’d used on K2 and Everest that I was going to use on Nanga Parbat. But I just had an old piece of webbing for a wrist loop… just a knotted piece of sling. They’d tease me and say you have to have at least a decent wrist loop.

I run a lot. I’ve been distance running as long as I’ve been climbing. I was a distance runner in high school. I know how my body responds to different things, so if I’m going to be climbing at altitude and I need to get my cardiovascular system fit, I know what type of training runs to do and how I’m supposed to feel to be prepared.

A lot of climbers these days have never participated in organized sports, where they were coached and [presented with] a more disciplined training process. I think it’s unique to climbing that if somebody trains for it, somebody else calls that out and says, ‘Oh, Steve is really into training.’ In any other sport, to train would be the norm.

I remember the late 1970s, I wanted to climb big mountains in Asia. But I never got asked to go on other trips with known climbers if I was going to do it, I had to do it on my own. I heard about the AAC, joined up, and went to their annual meetings. It was awesome I thought, OK, this is my tribe.

I grew up in a world where people, by the time they were 30 or 40, were old. They got caught up in their jobs and were basically just turning the crank…biding time until they died. It was an eye-opener that I didn’t have to go down that road.

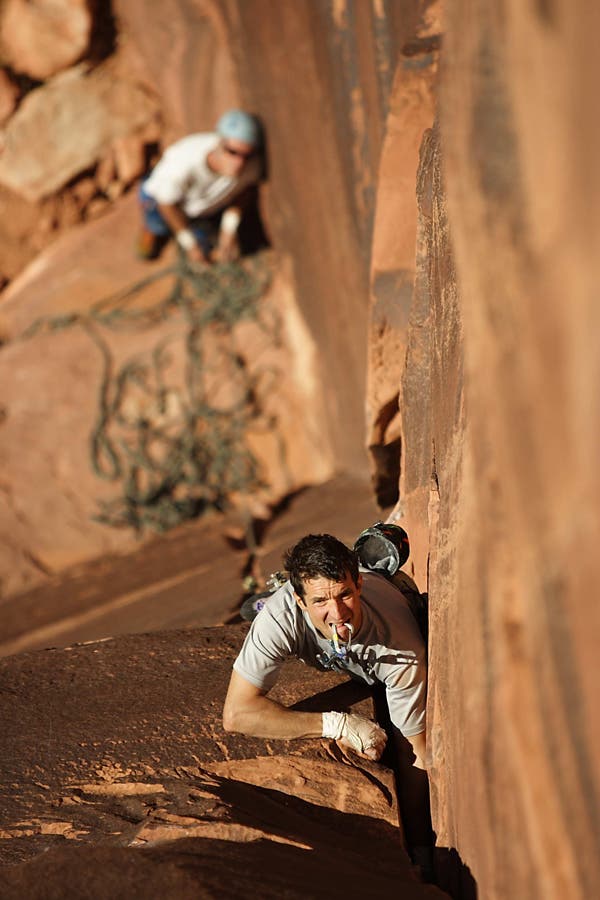

When Doug Chabot and I were on the Mazeno Ridge on Nanga Parbat, the weather was turning bad and I didn’t feel that good, so we decided to descend and come back up the Shell Route. We’d been talking to Steve [House] and he’d said, ‘There’s fixed lines; you don’t need anything to go down that route.’ So we thought, we’ll leave our rope, stove, food, and fuel here at 7,000 meters and grab this stuff when we come back. But the snow slope turned into a ridge and this big rock arête…There were no fixed ropes, just a drop-off. What we finally came up with was, on the way down we saw a little piece of rope sticking out of the ice, so we spent about three hours chopping 70 feet of rope from the ice. By then it was late in the day; we made an open bivy on this ridge. In the morning, we started downclimbing with the rope. We ended up making about five little rappels…

When I talk to high-school age kids who are interested in climbing. I tell them about how when I was their age, I was really passionate about climbing so I ordered this big-wall rack from Chouinard Equipment. I didn’t have a car, so I got my buddy to belay me so I could climb up the telephone pole in front of my house. I had all these blades I was pounding into the wood, and I had my aiders out.

When I was about two-thirds of the way up, my dad comes home from work. He’s a really nice guy but didn’t know anything about climbing, and so he pulls up in his pickup, gets out, and starts yelling at me, ‘What the hell are you doing? What kind of stupid stunt is this?!’ He told me to get down immediately, but I said, ‘That’s not a good idea,’ explaining that I can’t lower off these body-weight-only pitons. I told him I needed to climb up to the timber crossbar and put a sling around it and rappel off that. My dad was a mechanical engineer for Boeing, so he understood what I was telling him. Back in those days, you usually just did what your Dad said without a lot of questioning, so it was kind a teenage rite of passage to reason with him and have him agree with me. Those kinds of climbing experiences helped me grow up and be more independent. Seeing the old sling in the crossbar of the telephone pole helped me make the right decisions for myself later on.

I’d go down to Yosemite and do big walls with Alex Lowe. Alex was a big figure people would walk up and say, ‘Oh, you’re Alex Lowe! You must being doing some badass thing.’ Within 15 minutes, he’d get them talking about what they were doing. You’d see their eyes light up. That’s what the Alpine Club is about what Alex was at that time. We want to do that for the American climber.

I spent a lot of time going to the big mountains like in the 80s K2, Everest, and Gasherbrum IV, things like that and when we’d show up in the basecamps, there’d be people you knew. Over time, people going to the big mountains got supplanted by commercial groups, people who weren’t as experienced or who wanted to collect their Seven Summits. … I went on an Everest trip in 1994, just as that was really starting to get bad, and it was really depressing, because people were running around in the mountain not taking responsibility for themselves.

The focus of climbing was really shifting, and that’s when I started climbing with Steve House. In Asia, climbing 6,000- and 7,000-meter peaks it’s what the 8,000-meter peaks felt like in the ‘80s.

It’s hard to stay healthy. If I train as hard today as I did 10 years ago, I’d get injured. It’s all duct tape and bailing wire now. I go to the massage therapist, the acupuncturist I do all kinds of physical therapy.

I back off a lot of things. My success rate in the Himalaya is probably less than 30 percent. I’m not afraid to turn around.

MORE PERSPECTIVE: