The Dihedral Wall

"None"

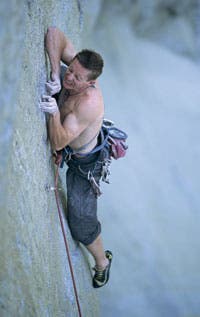

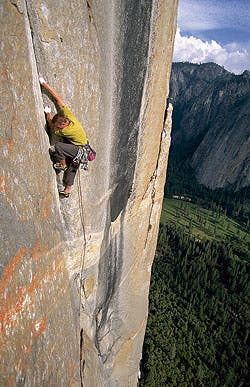

Caldwell on the fifth and last pitch (5.12d) of the lower dihedrals. After this, the next ten pitches of the Dihedral Wall are 5.13b (8a) or harder, save one 5.12d pitch, an offwidth flare.Photo by Corey Rich

“I don’t know if I have this in me anymore.” For the length of my professional climbing career, I shunned these words. I have always taken the theory that I cannot back down even an inch or I will never reach my true potential. But here I was, 1800 feet up El Cap, feeling like I might finally be at the end of my rope. My arms were seizing every time I lifted them above my head. Blood was seeping from holes in my fingers, knees, elbows, shins, and forehead. I had been abusing my body on this climb for over two months and I was tired. Deeply tired, in both body and mind. Several times over the past two days I had spent more than an hour on a redpoint burn, only to pump out or have a foothold crumble, sending me down to repeat the abuse. I had fallen over a dozen times, having to re-climb pitches each time, and it had taken its toll. Now I was only one pitch from sure success, feeling like I could go no further.

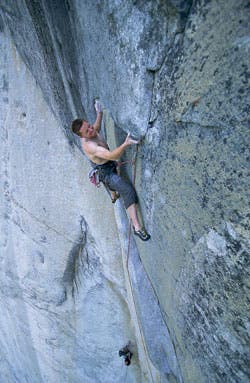

Pitch six, the route’s crux, moving out across the right wall of the lower dihedrals.Photo by Corey Rich

The pain and suffering started in October of 2003 when I decided that I needed the experience of soloing a wall. I chose the Dihedral Wall of El Capitan because it was one of the most obvious lines on El Cap, the third route accomplished on the wall after the Nose and the Salathé, and I wanted to recon something that might go free. I was not the first climber to think of freeing the Dihedral. Alan Lester and Pete Takeda free climbed fifty percent of the route in the early 1990s. Todd Skinner and Paul Piana worked on it extensively in 2001 and 2002, pioneering the variations that would eventually allow a complete free ascent. When I soloed it last fall, it looked nearly impossible. Steep, flaring dihedrals stretched on for hundreds of feet without break. The cracks were thin throughout the bottom half, only occasionally big enough to accept more than a willing fingertip, and up higher they became bottomless and flaring. Often the cracks petered out completely. Face holds seemed to appear, just big enough and close enough together to make me think the moves might go free, but I had serious doubts. If the Dihedral Wall could somehow be climbed, it would be one of the most extraordinary free routes I had ever laid eyes on.

The crux underclings on pitch six. At 5.14a, this may be El Cap’s hardest free pitch.Photo by Corey Rich

I came to Yosemite early this spring — alone, since Beth Rodden, my wife and usual El Cap partner, was still recovering from a broken foot. When I arrived in the Valley, the weather was crisp and clear — perfect for anything my heart desired. I spent my first days bouldering. Most of my bouldering time in Yosemite had been after big El Cap projects, and my memories were of mosquitoes and greasy fingertips, but this time I had perfect conditions. I had some of my best Valley bouldering days, putting up some new problems — yet something was missing. I wanted an adventure. I wanted to dive into something huge that would take over my time, drive me, and bring me to the next level. So I headed up on the Dihedral Wall. I worked the route solo at first, toproping on my fixing lines. Alone, I was better able to appreciate the beauty and magnitude of the climb. I did not have to worry about anyone else’s concerns, and this allowed me to focus more intensely. I got used to the silence. I memorized every gigantic dihedral, fingertip edge, and hairline fracture. I took time to watch the swallows tackle each other in mid air and plummet towards the ground, separating just before the treetops. I would say out loud, “That is so cool,” even though no one was around to hear me. The view from the route became etched in my mind, as did the thousands of moves I rehearsed. I was alone with my thoughts and motivation.

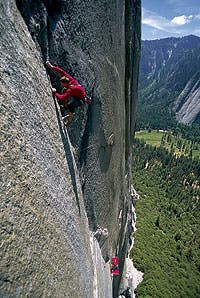

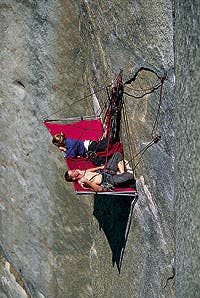

“The Ledge,” top of pitch nine.Photo by Corey Rich

The Dihedral Wall route consumed me. I climbed more intensely and for longer each day than I ever had before. I climbed four or five days a week from sunrise to sunset. On my biggest days I would start at five a.m., climb from the ground to the end of the last hard pitch 1800 feet up the wall, rappel back to the ground by noon, eat lunch, and then go bouldering until dark. I would call Beth at night and fall asleep on the phone. I climbed so much that my fingers wore down to bloody stumps and my toenails fell off. My muscles were so sore so much of the time that I forgot what it was like to feel normal.

Beginning the long 5.13b pitch into the Black Arch.Photo by Corey Rich

Trips home to visit Beth mainly consisted of sleep and food. “What’s wrong with you?” she would ask, but deep inside she knew. Returning to the Valley meant starting up my workhorse schedule again. At the end of each day I would stagger to the car, then try to repair my various wounds. I’d shove food down my throat as quickly as possible, usually cold burritos or sometimes just a PowerBar. I would find a place to sleep and pass out as soon as my head hit the pillow. On a few occasions I fell asleep sitting straight up while cooking dinner, only to be rousted by the rangers telling me I could not sleep there. The Dihedral raised my tolerance for pain and frustration. It also gave me great satisfaction. I was living each day to its absolute fullest. I was working toward a very definite goal and it was bringing me to a new level in my climbing. It may sound weird, but normally Yosemite makes me weak. I usually return home unable to do the most basic power problems or sport climbs. The huge days, endless cracks, and lack of powerful moves turn me into a 5.12 sport climber without fail. But the Dihedral Wall kept me strong. On rainy days in the gym I was stronger than I had been before the Valley season. Bouldering in the afternoons left me with a smile on my face because I was able to run laps on hard problems like Thriller and The Force. It became obvious that this route would be a huge step above anything I had climbed. It was absurdly sustained. Most of the existing hard free routes on El Cap had only a few 5.13 pitches, but of the first fifteen pitches of the Dihedral, one was 5.14, one 5.13d, three 5.13c, three 5.13b, and four 5.12. On top of that, these pitches were sustained. I had to really concentrate from the start to the end of each pitch — none were one-move wonders. A month into the project, Adam Stack joined me. The scene on the wall completely changed. He was fresh off a free ascent of the Salathé Wall and flying higher than ever. We spent hours on our portaledge together, laughing and telling jokes while talking about how lucky we were to be here, the most amazing place on the planet, working on such an incredible climb. With Adam, there was never more than ten minutes without laughter. He would claim that if he “squatted” in one place long enough he could own it, taking the Homestead Act of 1862 to a new level. (I had to break it to him that I doubted the Act applied in National Parks or El Cap, and that it had expired in 1976.) Whenever he would free a move or pitch for the first time he would say, “Do you smell something? Oh yeah, I’m the shit!” Adam’s energy transformed the effort and helped push me even harder. After another month, the route started to come together. I could link long sections of pitches, then entire pitches, and soon I had toproped most of the hard climbing. I had originally thought of this as a recon season, since Beth was out of commission. Now, with the perfect weather and the amount of climbing I was doing, I was fitting several seasons into a couple of months. I developed a plan of attack, and picked a style for my ascent. Climbers spend countless hours debating style in an attempt to establish a social pecking order, and honestly it reminds me of the reasons I did not like high school. I decided to avoid hanging belays and climb from stance to stance, in a continuous ascent from the ground, because it was the best style I thought I could pull off. I believe people should always strive to do climbs in the best style they think possible, but never criticize others for what they choose to do. El Cap is for having fun and having an adventure, not having fights and criticizing others — which does nothing but boost egos and show disrespect for the other people who share your same passion. As long as you are not harming the rock or the route for future ascents, and you are honest about what you have done and your style, you should be able to climb in whatever fashion you want. Beth’s foot was finally out of the cast, and she was now at her parents’ house in Davis, only a three-hour drive away. When I told her I thought I could do the route, she offered to come along as belayer. On the wall she wore one normal approach shoe and one big mountain boot to protect her injured foot. It looked like she couldn’t decide whether to go running or alpine climbing. Adam also volunteered to help out. I would have been completely astonished by their generosity if I hadn’t seen it so many times before. They gave the moral, emotional, and physical support that would be as crucial to my effort on the Dihedral as any aspect of my climbing. Beth laughed off the sacrifice by assuring me that she could miss a few episodes of “Trading Spaces,” and Adam was up for a few good days of jumaring and jokes. Three days before we were to start, Adam and I hauled five days worth of supplies to the top of pitch nine. This prep day would allow us to climb without hauling for the first two days. As everything fell into place I felt an increasing sense of excitement. Something started to grow inside me — my heart rate increased and I spent the nights tossing and turning, rehearsing the climb in my head. When should I start? How fast did I need to climb? How many times could I fall before running out of energy? I visualized the moves and gear placements over and over again: blue, then purple, then baby yellow. I was excited about the prospect of success and frightened of failure. So much was invested.

The upper crux of pitch seven.Photo by Corey Rich

We began climbing at five in the morning on May 18. The weather was unseasonably cool, and perfect for free climbing. The rock was polished and the finger locks far apart — every time I reached I feared that my feet would slip and I would go skidding down the wall — but as the ground receded into the distance I got into the swing of things. I began to find the rhythm I had had up here for the past five weeks. My conditioning paid off and I climbed the first four pitches in about an hour and a half. Beth said she was jumaring slower than I was climbing 5.12, and I was spurred on by that thought. On the fifth pitch I forgot half the rack and had to do twenty-five-foot run-outs on 5.12 climbing. I took it in stride and by the time I reached the crux pitch, at about eight o’clock, I was feeling confident. The crux pitch was a 120-foot bulge, overhanging for the majority of it, where the route exits the lower, left-facing dihedrals and moves out right onto the steep wall near Cosmos. It almost seemed like a bit of Ceüse transported to El Cap. When working the route I was never able to link this pitch on toprope, but I was hoping that the psych of the redpoint attempt would help me. I was pretty sure that this would be the hardest free pitch on El Cap, and I knew I would have to climb flawlessly to do it. Remembering to breath, remembering the sequence — and most of all remembering to try hard as hell — were all things I needed to do to get to the belay. I gave Beth a kiss and set off. I started laybacking up a one-foot-wide dihedral with no crack in the back. With few footholds on the smooth granite, I was only able to stay on the wall by pinching the outside corner of the dihedral and pressing my feet hard against the wall, testing my shoe rubber to the max. I felt strain in my back, fingers, and neck, and just as the rock got steeper the seam opened up enough for fingers. With no footholds in sight I had to continue climbing without pause. The crack ended and I made a full span right to a sloping ramp, then dynoed for a shallow finger lock. I was pumped now, and my body was visibly shaking. I did not even hear Beth and Adam’s screams of encouragement, which left them hoarse. Already at my limit I entered the next sequence, pressing my thumbs up underneath a small roof and stretching to an undercling far above my head. As I pulled into the undercling I began to feel dizzy. I fumbled for high crimpers, then pulled over into a “5.13 stance” on the slab above. My legs were shaking uncontrollably and my mind was racing. “Ten more feet and it will be over,” I told myself. I focused, composed myself, and then delicately traversed on micro holds to the stance at the belay. I felt overwhelming relief, and thanked my ten years of dedicated sport climbing for giving me the forearm endurance to get through this one. I had managed to do the crux of the route without falling. But I still had a hell of a lot of hard climbing ahead of me. Beth and Adam jumared up and we set up the portaledge so I could recompose. Adam started talking about his upcoming trip to Alaska. “Maybe if I buy one of those bear rugs and wrap it around myself,” he said, “the grizzly bears will think I’m one of them and will not eat me.” With a puzzled look on his face he continued, “I just hope that a male grizzly bear doesn’t mistake me for a female.” Beth shook her head. My nervousness was quickly evaporating. As I racked for the next pitch I tried to block out the visual that Adam had just put in my head and focus on the climbing ahead.

Pitch eight, the Black Arch (5.13c), “one of the most striking features on El Cap.”Photo by Corey Rich

The next pitch was 5.13b, very slabby and sharp — it reminded me of Lurking Fear. Doing it first try would be critical to saving my skin for the rest of the climb. I balanced my way from razor blade to razor blade and concentrated on keeping myself steady. I knew that the slightest shake would cause a foot or hand to slip. Beth and Adam were silent while I climbed; the only noise I heard was my own breathing. I slowly crept from hold to hold and after nearly an hour arrived at the anchor. I had completed half the hard climbing for the day and it was only ten in the morning. I was excited, but also knew that I would not be as fresh in the afternoon, not to mention the days to come. I knew that I was going to put my body and mind through incredible stress the next few days. The next pitch was the Black Arch, a 200-foot arching crack and is one of the most striking features on El Cap. The sun hit the wall just as I started up. Usually for me this means the end of the climbing day, but the cool temps, along with a breeze, kept the conditions good. I felt a bit hesitant, and slipped off after about twenty feet — my first fall of the route. I rested ten minutes, pulled my rope, and tried again. This time I pumped out after thirty feet. Figuring I had not rested long enough, Adam set up the portaledge and I rested for half an hour. “I can’t believe you are still trying to climb. Normally you melt when the sun hits you,” Beth said, trying to cheer me up. Next try I made it about thirty-five feet, then pumped out again. I started to worry if I had this in me. I rested for about forty minutes, pulled the rope again, and went for it, desperately managing to climb to the first rest, forty feet up. My confidence was totally shot. For the next hour and a half, Beth and Adam pumped me with encouragement. “Try hard Tommy, you can do it!” they would yell up at me, but in my head, I told myself, “Don’t be such a pansy, just suck it up and climb.” I slowly crept up the arch, resting for long periods whenever I could. I made sure my feet were placed perfectly and my movement was exact. I felt like a sloth moving up the wall. Just as Beth and Adam were about to fall asleep I reached the anchor. Completely exhausted, I fixed the rope and waited for them to arrive. I only had one more pitch to go before the comfy bivy ledge with all of our stuff, but it was the second-hardest pitch of the climb. I was in pain, my toes were throbbing, and there was blood seeping from underneath three of my fingernails. I pulled out of the Black Arch into a series of underclings and sidepulls separated by gaps I could barely connect with the span of my arms. The pitch defied all free-climbing logic — it is the only slab I have ever climbed that maxed both my finger strength and arm power. I wrestled from feature to feature, pushing the pain to the back of my mind, and arrived at the hardest single move of the climb, a six-foot gap, blank except for a single shallow divot. Glad for the countless hours I’d spent bouldering in the Valley, I gritted my teeth, pulled hard, and stretched for the divot. Matching one finger at a time in the divot and hopping my feet to higher smears, I began to fade. In a panic I slapped a sloper above. My feet slid out from under me as I matched. I smeared my feet high, sagged back on my arms, and dynoed with my last ounce of energy. My fingertips tagged the edge of the jug above — and I was off.

Moving up pitch nine (5.13d), onto a slab that “defied all free-climbing logic” and held the route’s single hardest move.Photo by Corey Rich

I shot backwards, tumbled down the wall like a pinball, and came to a stop twenty-five feet below. My last bit of energy was gone. I pulled on gear through the crux and climbed to the ledge sixty feet above. Beth and Adam soon followed. As I sat on the ledge I could feel my pulse in my fingertips and toes. I had just done more difficult rock climbing in a single day than I ever had before, but it came at a price. I was trembling from the pain, and had serious doubts about tomorrow. Beth and Adam noticed my distress and did everything they could to help. Beth gave me a massage and Adam talked about riding grizzly bears into basecamp. By the time the sun went down I was feeling rejuvenated, and decided to give the pitch another try. The outcome was almost identical to my first try. I gave it one last try before dark, and fell lower. As I got back to the bivy, we settled in for the night by headlamp. We had been up at three in the morning and gone until nine at night, but still I wanted more daylight. That is one of the many things I love about El Cap — when you are up there, you get to climb as much as you want, from sunup to sundown if you like, or sometimes longer. Beth was particularly drained — eight months off, then straight to El Cap — but she still managed to give me a massage to help me sleep. “Where’s mine?” Adam asked. “I see how it is, I can’t climb 5.14 up here, so I get the raw end of the deal.” I woke up the next morning feeling pretty sore but confident. I wolfed down some canned peaches and beef jerky and lowered down 100 feet to warm up. The first few moves felt horrible, but after about ten minutes my fingers and toes numbed a bit. Adam and I rappelled down to try pitch nine again. I powered quickly through the bottom, determined not to let anything stop me this time. I quickly ran through the moves again in my head. I gritted my teeth as I climbed and made it past the divot without error. I matched on the sloper, got my feet up — and then did something that goes against everything I know about climbing hard: I hesitated. Beth and Adam simultaneously started yelling, “Come on Tommy!” I sagged back and dynoed. This time my fingertips caught the hold. I let out a whoop of excitement and scrambled onto the bivy ledge. The rest of the day was spent climbing the next three pitches: a 5.13c flaring hand and fist crack in a corner, a 5.13b rounded layback, and a wet 5.12d offwidth. If any one of these pitches were on any other free climb on El Cap they would have individually constituted the cruxes, but on this route, they seemed to fall by the wayside. I fell once on each pitch and managed to summon enough energy to do each on my second try. By the end of the day my toes felt like they might pop right through my climbing shoes. All I could feel was pain, but I was finished with a lot of the hard climbing. Things were going well. I was starting to believe I actually might have a chance to send this monster.

Visualizing below the Black Arch.Photo by Corey Rich

That night Adam headed back to the ground to teach a clinic. It was weird to say good-bye in the middle of a wall. “Don’t think that you’re allowed to come down, too.” Adam said. “If you run out of supplies, I’m coming back up with more.” Beth replied with, “Yeah, I’ll stay up here even though it is ‘Trading Spaces’ marathon weekend.” We sent Adam down with a walkie-talkie so he could make us laugh from 1500 feet below. It was hard to see him go, but I still had Beth, who has been a part of every free route I have done on this big stone with the exception of my first time on the Salathé. It amazes me that she is always willing, no matter what the circumstances — even a broken foot — to come and help me up here. “I love being up here with you,” she said to me. “It inspires me to watch you climb up here. I’ll do it anytime.” That night I barely slept. I lay awake listening to the sounds of the waterfalls and trying to ignore my throbbing fingers and toes. I watched the “half sky” view of the stars and enjoyed the calm of night on El Cap. No noise of cars, motorcycles, or construction. I also thought about the next day’s climbing. I only had three hard pitches left. One was a completely wet 5.13b that because of its unpleasant nature I had barely worked on. Then, a 5.13c boulder problem, then another 5.13c pitch that was the scariest pitch of the climb. I tried not to toss and turn too much in the portaledge, so at least Beth could get a good night’s sleep. The next morning I crawled out of my sleeping bag with my eyes half closed. By the time I was racked up and ready to go I was already bleeding from my fingers and knees. I stared at the pitch above, an arching crack, black with water and dripping with mud. Climbing at this point was no longer fun; it was now just about getting it done. No longer did I think about the joy of the movements or the beauty surrounding me. I focused on the next belay. I finished the wet pitch and lay on the precarious ledge that was my first optional belay. Ideally I wanted to link the wet section into the next pitch, making it another monster, but if I fell on the boulder problem above I was resolved not to re-climb the wet 5.13. I lay on the ledge for a half hour, rehearsing the upcoming moves. Then I committed and cranked through the V9 boulder problem. As I neared the final jug, I pumped out; I caught the jug with my hand, but my feet swung too wildly and propelled me into the air. I lowered back to the ledge, pulled the rope, and sent the pitch next try. I was now feeling the full effects of three hard days on the wall. Although just one more very hard pitch remained, I thought, “I don’t know if I have this in me anymore.” Here I was, 1800 feet up El Cap, near success, but feeling like I might be finished. Would I feel better later today or tomorrow? Just as I was about to give up and rest until evening, Adam’s voice came over the radio. “Nice job dude!” he shouted. “I got a whole crowd of people down here waiting to see you send the last hard pitch.”

The tenth pitch — another 5.13c to round out the day.Photo by Corey Rich

The solitary nature of the challenge is one of the things that draws me to big-wall free climbing. You never have that group energy you get cragging. But this time, a crowd of people pulling for me 1800 feet below gave me just the boost I needed. As I started climbing, my whole body was quivering with pain and fatigue. I had been concentrating for three days straight and my mind was tired. I felt like giving up — but I wanted to give the crowd the show they came for. “It is almost over,” I told myself. I moved from a shallow groove to a small layback crack that marked the last ten feet of hard climbing. I gritted my teeth a little harder and started pulling. If I fell here, a fixed pin that was at least twenty years old and driven into mud would hopefully catch me — but I did not want to test its integrity. I pressed my bloody, swollen fingertips against a tiny sidepull and smeared my feet into a glassy dish. Just as my fingertips reached the next hold, my foot slipped. Panicking, I desperately re-smeared my foot and shot my hand into a bomber jam above. The remaining thirty feet of the pitch was the most carefully climbed 5.11 I have ever done. When I reached the ledge I heard faint screams from below. I turned to face the crowd, threw my hands in the air, and screamed as loud as I could.

Postscript: Almost three weeks after the completion of the climb I am still tired. I tried climbing for the first time the other day and felt horrible. I have felt lethargic ever since, but at the same time deeply satisfied. It was brought to my attention recently that, foot for foot, the Dihedral Wall has over twice as much hard 5.13 to 5.14 climbing as any other free route in the world. I have been back on the route twice since the ascent, once to take pictures with my good friend Corey Rich and once to shoot video with Heinz Zak. Both times, the beauty of the climb again struck me. Heinz even called it the “King of El Cap free climbs,” and I agree. I truly had to rise to a new level to complete this route. I look forward to many more days up on El Cap, by myself or with friends, but I doubt that I will ever do another climb as amazing as the Dihedral Wall. But then again, you never know. Tommy Caldwell, 25, is America’s best all-around rock climber, climbing 5.15 sport, 5.14 trad, and V13 on the boulders. He has free climbed El Cap by six routes, three of which he established. This is his first feature for Climbing