THE MEXICAN GUIDE at EL GRAN TRONO BLANCO

"None"

If you want a climbing article, a pitch-by-pitch travelogue on this secluded place, this story ain’t for you. I’d rather tell a saga of our encounter out there, with a saint of a man on this rugged section of Baja. This piece is a review of a fellow who jumped out of the chaparral and helped us survive. This tall tale is a tribute to our friend who taught us the meaning of a simple Spanish word that few north of the border really appreciate or understand: simpático. This recounting tries to unpack our amigos way of saying, we human beings no matter our creed or breed or what we read are “Una fatsa, una ratsa” one face one race, the human race.

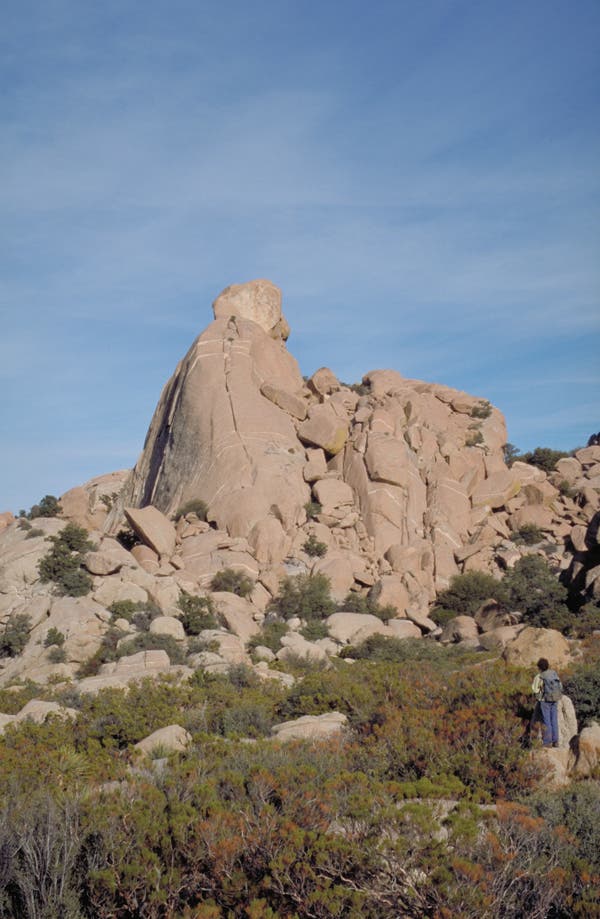

In our haste to get to the base of a climb, it is not unheard of for us to get disoriented for a while. To be so totally FUBARed looking for this Trono Blanco granite dome nearly the size of Middle Cathedral Rock in Yosemite, where we needed a Mexican guía guide to get us there, well, this is how I recall the experience.

Mi amigos, ¿qué pasa? ¡Dónde vas!¿Chingada? He came out of the chaparral like a jaguar, stealth and pronto, a middle age cat, who, if he wanted to, could of captured all three of us at once and hauled our asses into the bush for a meal. A day time premonition who materialized about where the “fork in the dirt road” was supposed to be.

He was maybe my middle age, and guapo or good looking, my build, about 5 foot 7, all alone, graying beard, likewise the color of his shoulder length hair. His skin was the hue and texture of my brown leather boots he didn’t need chaps to walk through the cactus and thorns. Eyes were sad, I think they had seen a lot of misery, and much joy. Expression somewhat like Carlos Santana viewed in a DVD concert. Voice akin to a 40 year old fine mariachi guitar well played. Sombrero a yucca woven model well used. He was wearing what appeared like an old pair of white Gramicci climbing pants, huaraches, and a Patagonia Hawaiian shirt, logo and all. Nice but ragged attire for this first weekend in November expedition into the Sierra Juarez region of Baja Mexico. Elevation approximately 6,000 feet in a bizarre mix of scattered ponderosa and pinyon pine, palm, yucca, agave, succulents, cactus and chaparral species of very pointed, rough and waxy leaves.

Our ghost looked vaguely familiar. In my halting pocho Spanish I asked, Te conozco? “Do I know you?” He looked at me for a while and smirked, Padria sir, could be. He said something about spending time in California, Estados Unidos, and Aztlán. On our truck stereo the Grateful Dead were jamming away, “. . . The wheel is turning and you can’t slow down.”

We were three college grads, all smart enough to follow topos up big walls in Yosemite, take verbal beta from friends on how to get somewhere, and two of us where geography majors with courses in cartography under our climbing harnesses. We had no GPS or cell phones, just us and we expect “us” to get us out of trouble if we got in such an ordeal. The Three Musketeers, one for all and all for one. Dan and I had worked for Outward Bound. Joe and a pal had ridden their two wheeled aluminum mules all the way down Baja to Cabo San Lucas. A trio of boy scouts prepared for anything. I had once been given directions in San Diego on how to hook up with a dude in Tijuana way off the beaten path and down or up many alleys. Gail and I found him, no problem. I had volunteered on the Arizona zona seca frontera with a group dedicated to providing H2O tanks for the northbound desert travelers. We were all practiced south of the border.

We had been dead set on getting to this big wall, machismomaxamundo! We knew we had it in us to find a way through. On this dusty dirt road looking for the White Throne we tres amigos were in mucho problema(!), so turned around we couldn’t see right from wrong, and our new friend our milagro or miracle seemed genuinely interested in helping us out of our fix.

We were standing around our beat up 4X4 pickup by now beginning to talk with . . . ¿Quiéneres? Who are you? “Amigos, looking for Trono Blanco?” Yes! Si! ¿Sabes, dónde estamos? You know where we are?

We left San Diego crossing The Borderat Tecate at about high noon. ¡Salispuedos! Get out (of town) while you can! ¡Arriba! Heading east on Hwy. 2 toward Mexicali, to the turn off at La Rumurosa gas and chimichanga was relatively normal, even if we were in another country. But once past the highway now on the main dirt road, there are hundreds of other paseosucker sand trap lures, flat tire routes steering us every whichaway but the right way. I was reminded of my water color painting I did in elementary school: The Plumbing black pipes going left and right off the “main line” at ninety degree angles and forty fives. T’s and Y’s going crazy, even circling back on the “main line.” Deja vous. I was at our crux and hadn’t even set foot on stone. We were in need of Baja Triple A: Automobile Association of Aztlán (Their Country, the Southwest).

Me llama Chewbacca. Chewbacca?! We looked at one another. Chewie OK? Si.¿Cómo te llama ustedes? I went first, Preston, Daniel and Joe followed. We shook hands. His grip was strong, callused, but soft. Con mucho gusto!

Not much is written about this Shangri-La dome land. For good reason. To get to El Gran Trono Blanco can be a mammoth undertaking even before you leave your North American casa, of choosing the right team (no bickering down here, ya better get along), gathering information, working out logistics (gotta have a plan), and building a car parts repair cache such as an electric cigarette lighter air / tire compressor (for when we flatted and had to use our tire “hole” repair kit, or fill up a slow leak), can of fix-a-flat in case the little compressor motor burned out or another set of climbers needed help, extra water hoses (go to a auto junk yard and pick a part), spare fuses, quarts of oil etc, and antifreeze (we forget nearly it all!). Plenty of cash well hidden in case we needed to talk our way out a police discussion. We did have a stout battery (oversize for our rig) and jumper cables, a small tool bag, and duct tape and bailing wire. There is more . . .

Take a Wilderness First Responder or EMT course and bring a medical box that includes suture packs, Morphine, Codeine, Dramamine, combat size compresses, a snake bite kit and the like (a bit of an exaggeration, but not much). We had a few bandaids, some aspirin, athletic tape and super glue. No chance of a rescue down here. Then set off to accomplish the mission, or at least die trying. Knowing the lingo, at least on a confident elementary level is very important. We left our Spanish phrase book at home. Who planned this trip anyway! I was our translator and my Español was piss poor. Praying to El Señor, El Verbo, Mother Mary, and St. Christopher Patron Saint of travelers in desperate situations, now that was a smart thing to do! Still, we were trespequeño turistas, three desperados in a laughable mess.

Chewie waited with us as we thought about his future and ours. Odd, and I hope this doesn’t sound like a stereotype, but Chewie didn’t smoke, neither did any of us. We pulled out a six pack of Anheuser Busch’s finest, Joe handed him a cold one and said, “This Bud’s for you.” ¡Salude! Chewie looked at our ropes and tack, he shook his head with approval, ¡Alpinismo! By the end of the second six pack and a bag of chips and Pace hot Salsa we were in agreement. Chewie would be our Moses leading us on to the promised land. Who is this guy? And he knew more English more than he let on.

What should we call our south of the border friend? Mexican? Mestizo? Bracero? Campesino? Paisano? I thought, sooner or later we would find out where Chewie was from, when and how long he was in El Norte, and maybe for what reasons. For now, we being but gringo gabacho babosos didn’t know anything beyond our amigo’s name and his friendly face, nor did we care. Chewie seemed puro and honest. And we liked him. We were in for an adventure (to arrive), little did we know how interesting a mountain we were going to climb.

Chewie asked about our water supply. This topic was very important to him, we saw it in his body language. ¿Cuantos gallons, agua? I counted to twenty on my fingers. Veinte aqua aqui.Bueno.

Chewbacca had one errand to run before we left, said he’d be back pronto. He turned back into a jaguar like a shift changer, jumped into the bush and was gone. An hour later El Tigre returned with a tattered and bleached-by-the-sun climbers pack, a frying pan, a dozen eggs, tortillas, frejoles in a big can, chilis, red peppers, onions, garlic cloves, cilantro, tomatoes (we had the cheese, lettuce and cabbage), Cholula hot sauce, and a case of Tecate Beer. Where’d he go? Joe loaded the eggs into our ice chest, we wasted no time chugging another cerveza.

Our truck tailgate was down and Chewie emptied most of the contents of his rucksack. Out he pulled a long sleeve T shirt with the Go Climb a Rock stenciled on the back (no lie). He also had a Grateful Dead T shirt with the dancing skeletons artwork. A white baseball hat with the Mexican national emblem on it that looked as beat up as my Corona hat. A Blue Water climbing harness came next, the kind my climbing wall manufacturing company sold to gyms who had our walls installed Sport Rock International, Paso Robles. Hum. He had an ATC belay plate, well used, chalk bag, and . . . who is this guy? Then, with much anticipation on our part, next came, a small wool blanket, then . . . those shoes, I have a pair of those old boots: Boreal Firés! Chewie saw me stare at the Spanish botas. He smirked, picked one up said, Mi amigo es Chongo Chuck, and his rubber. ¿Tu sabes Chongo Chuck? Si!

This encounter was getting stranger and stranger by the moment and we hadn’t even got going yet. One more item to inspect the quart and half glass bottle. Dan carefully picked the jar up and I asked, Que es esto? Chewie we were finding out, was a most versatile Mexican. This small jug contained his very own signature tequila. ¡Hijola! For Dia de los Muertos (Dan now cradled the bottle like it was a little baby).We again looked at one another to try and remember exactly what the Day of the Dead was is all about. Chewie was willing to be with us for at least a day during this solemn remembrance, oh yah, to celebrate the death of their relatives and their spirits returns during this fall memorial. Looking north, being so close to La Línea, La Frontera, the Mal Paíz, El otro lado, I imagined Chewie had relatives or friends out there.

What must it be like to cross the border in the middle of summer, with too little water and too many La Migra searching for you? To loose a family member to dehydration and death! Chewie was animated and talkative as we stashed his gear in the bed of the truck.

Joe and Chewie padded the Bell Jar care-full-ee with our sleeping pads as if it was Nitroglycerin soon to explode with any jolt. We wanted that explosion to happen in our brains. We hopped into the king cab truck and us dumb sheep followed the directions of el pastor. Within an hour, as I remember it, we were at the smaller domes, just passed them we found a place to camp. Like Joshua Tree with no neighbors. Our oasis.

As we unpacked what we immediately needed, more beer and chips, lawn chairs and such, we relaxed in the late afternoon setting sun. Chewie wasted little time preparing for the evening meal. Joe helped. Dan and I got the campfire going. We had a pound of ground round (we were going to make hamburgers!), Canola oil, Chewie the pinche or cook had the rest of the ingredients laid out like he was the Cajun chef Paul Prudohomme, and was now beginning to concoct tacos de fantastico on our Coleman stove. More chips and salsa, we were listening to the Flying Burrito Brothers. “. . . Wild horses couldn’t drag me away / wild horses couldn’t drag me away.” Chewie said that after dark on the radio AM dial, we would be able to tune into a station all the way south to México Ciudad. A thousand mile radio signal.

As I watched the Mexican Magician prepare our meal his treat, I thought of the famous artist Picasso and his sculpture, The Goat. This is how I saw Chewie. Tough, rugged, duro, funny, yet polite, kind, even compassionate. Servant and artist. A Mexican Picasso.

¡Comida! We laid out our dinner in an organized fashion on the tailgate, tacos, chips and salsa, beans, cheese, cilantro, cabbage and lettuce, onions, and cerveza. We all had a chair to watch the sun set. We were now the Four Musketeers eating with gusto, now well satiated and well in verse. I am the quiet one, the listener, many call me Deep Thinker. Joe and Dan are more entertaining and conversational. Chewie was now part of us, or we were part of him, a gregarious cuatro amigos chowing down. Dinner over we bused our tables, cleaned up, and prepared for the next course.

By the time the stars came out we were well into our conversation about life on the border. Chewie brought out his agave liquor. “I want to make mescal as good as Tish Hinojosa plays Tijano and TexMex ballads. I’m not there yet, wrong kind of agave here.”

For some weird reason we brought four heavy glass tumblers, small size. For our Bud beer!? Around the small campfire Chubacha began with a short recitation of Los Dias de los Muertos. A thousand year old celebration (Aztec origin) to help Hispanics grasp hold of their ancestors who were now alive in the spirit world and we were celebrating with them. Kind of a modern day version of Jesus’ blood and body coming to life in all the saints. Chewie pulled one more item out of his pack, stuffed in a pillow case a human skull. He now had on his Grateful Dead shirt.

“This calavera represents my relatives and friends out there on the desert floor who did not make it.” He sat the head on a stone like an shrine with tequila in a shot glass, some water and chips and salsa next to the fire. With a pour of the Bell Jar, we tasted Chewie’s mescal. ¡SALUDE! His Distilado de Agave was not Patron. Better than Jose Cuervo, that’s a fact. “I can only make a little at a time.” In Spanish Chewie raised his glass to his relatives. As a white boy barely understanding elementary school Spanish, I was at a loss to what Chewie said. No worry. Chewie knew if we got hold of the basics, we were better off than before, and we would have bunches of fun doing it! Chewie sang a song, he said was written by Flaco Jiminez, Un Mojado Sin Licencia (A Wetback Without a License).

We hear a coyote sing another song in the distance, then several joined in the chorus. Chewie: “Coyote is much more than a wild dog in the bush. Coyote is a spirit, a trickster, and possibly a bad omen. To hear coyote is to think, trouble is near.” He also said, “Don’t worry, they know we are celebrating my family, and we have our holy site right here.” We drank more tequila, ate chips and salsa, drank more beer. And toasted Chewie’s family that was alive and with us.

On the AM radio, we heard, Tres Veces Mojado (Three Times a Wetback). Chewie interpreted: “When I came from my land El Salvador, with the intention of arriving in the U.S., I knew I would need more than courage . . . There are three borders I had to cross, across three countries I walked undocumented. Three times I had to risk my life, that’s why they say I’m three times a mojado . . . (In Arizona) I pushed myself to the middle of the desert (and) by luck a Mexican guy named Juan gave me a hand . . .”

Chewie gave us a hand. We were thankful. Sleep comes easy when you are relaxed, feeling safe. Just before bed, with the fire now glowing embers, Chewie did a remarkable thing: he put a candle now lit inside the skull, and this skull glowed through the eye sockets and mouth. Hasta manaña.

Next morning at dawn, Chewie and I were up, stirring the fire to life and making coffee. We had brought a pound of Guatemalan beans. Perfect start for our climbing day. We had a French Press, filters and a cone, cream and sugar. Joe and Dan smelled their wake up call and Chewie was busy getting breakfast ready: huevos rancheros. Cooking pot clean, pan and skillet also, more coffee, now time to think like alpinists. What to climb?

We were in complete agreement, our ascent would be exploratory, because we would be back. Chewie had a suggestion, a route he knew called VW. Maybe 5.9, much 5.7 and 5.8, ten or so pitches, a way around a chimney with a few aid moves in it. Sounded reasonable. Chewie was our leader and we prepared our truck for our absence, stowing everything in the cab, leaving a note saying nothing in here is valuable, and taking out our stereo and hiding it. We took off, then down the arroyo and . . .

As we stepped down and around the cobbles, talus, and scree, Joe as he let gravity carrying him onward had a rattlesnake strike between his legs, a rather lethargic strike as the morning temperature was well below 70 degrees. Still it set José into flight and Chewie into the bush after the reptile. He came back out holding this serpent as if it was one of those trick toy wooden snakes that seem alive. This snake WAS alive, and we were a little freaked that our friend was so calm. I said, “Who do you think you are, Don Juan the Jacqui medicine man?” Chewie smiled, “You’ve read Carlos Castaneda!?” Our jaguar put the serpent down, it slithered into the shrub.

As I said at the beginning of this tall tale, more important than the great climb was the great camaraderie we four were sharing. At camp that evening we were stoked, and though the beer was warm, so what!? More chips and salsa, plenty of cheese and tortillas, chilis and peppers for quesadillas. More tequila around the fire. Celebration is a fine festival.

We were, to Chewie, in simpático. We understood Chewie, his take on the Day of the Dead. Joe asked, “Chewie, what is La Raza?” Chewie, “You are La Raza Cosmica. The cosmic Race.” Chewie reminded us again, we are “una fatsa, una ratsa, one face, one race, the human race.” Though La Raza is sometimes depicted as super Mexicans Latinos Chicanos Hispanics ready to take back the Southwest U.S.A., Chewie broadened and mellowed that definition to include us. Joe and Dan are both dark skinned, though I am adopted (Tierradulce or Sweetland) my birth mothers last name was (is?) Sanchez, and mi esposa es una chicana. Chewie: One face, one race, the human race.

When you put it that way, there is not much room for prejudice, racism, or bigotry.

Dan asked Chewie, “Do you ever take people across the border? “Sometimes, but I am no coyote they charge way too much money and are dangerous they get my people killed, and I’m no mule I hate drugs.” He sipped his beer. “I have gone to coyote school down . . . “ Chewie pointed south, “I know many routes. I am going to guide a family across the border starting in two days, porgratis.” More beer is passed around. Rock on, essa.

Chewie looked north, “Mexicans crossing the border are Los de abajos, the underdogs. I am their guia. Thousands of my countrymen and women, children and grand folks cross every day. It is like when America was in the Viet Nam War. The North Vietnamese came south along the Ho Chi Min Trail, and your army and air force couldn’t stop them. At the DMZ (he used the phrase, sin frontera, land without border) between the North and South they crossed. No fence or wall or amount of border patrol soldiers could halt the compesinos from getting south to their promised land.” I thought, like ants on the march, nobody can stop them from their mission. “A lot of North Vietnamese peasants and soldiers died along that trail. There are many thousands of graves out there on those trails,” Chewie pointed north with his head.

I thought of the song by Woody Guthrie about Mexican immigrants, mojados or wet backs, picking our fruit and vegetables, Deportee: “Some of us are illegal . . . some not wanted . . . They chase us like outlaws, like rustlers, like thieves. We died in your hills, we died in your deserts . . . we died ‘neath your trees and we died in your bushes, both sides of the river we died just the same.”

Chewie pulled out his skull and set up his alter. Chips and salsa, then tequila was shared like communion. We were in church and Chewie was el pastor. We talked about his family in Mexico, in Baja, in America, or as he put it, Aztlán (the mythical land where norte and sud bled with no border), how many times he has crossed the invisible zone, his many dangerous trips, toils protecting the paisanos, and snares by banditos and snakes and La Migra. His rescues of lost families dirt poor, in the mal pais dry as a bone land where vultures circle overhead looking to scavenge a meal. Chewie changed subjects and asked about our families. We were one family now.

Packing up our evening supplies, making ready for bed, Chewie asked us all, “I want you to experience what my people must endure crossing the border. Come with me in two days.

To be continued . . .