The Snows of Genyen

"None"

Inside the Search for Charlie Fowler and Christine Boskoff

Two of America’s hardiest alpinists, Charlie Fowler and Christine Boskoff, went missing in the eastern Himalaya last December during a mission to climb untamed peaks. As the days ticked by, friends began to worry: These were not the kind of climbers just to disappear. Fowler and Boskoff were mountain-hardened veterans with 8,000-meter summits, wild icefalls, and stout rock climbs under their belts. Were they lost in the backcountry? Being held incommunicado by unsympathetic authorities? Or had they decided to extend their trip? Ted Callahan, a friend of Boskoff’s and one of her Mountain Madness guides, takes you firsthand inside the epic search for the late climbers.

Charlie Fowler must have been having a fine day. Mild temperatures and unusually stable weather (except for some recent snow) had brought the summit of one of the last peaks on his list within reach. He was climbing with the woman he loved, Christine Boskoff, and by any standard they were having a great trip: an ascent of the coveted and oft-attempted Yala Peak (5,820 meters) by a new route and a nearly successful first ascent of the officially unclimbed Jampalyang (5,958 meters). Now, the pair, two of America’s best alpinists, were trying a new route on Genyen (6,204 meters), a sacred, beautiful mountain in a remote valley in China’s Sichuan province, before returning to the States.

On December 4, 2006, Fowler and Boskoff missed their flight home. Two days later, friends in Telluride, Colorado, and Seattle sounded the alarms — contacting the U.S. consulate, reviewing emails the couple had sent from China, searching Fowler’s computer files, and tapping into the climber grapevine. Based on information gleaned from Boskoff ’s last email, sent November 8 from the small town of Litang, they planned “one last two-week peak bagging excursion to the Genyen area.” Little else was known. “It was totally unlike Chris not to be in email contact for so long. If she had changed her plans, she would have told us,” said Mark Gunlogson, president of Mountain Madness, the guiding service he co-owned with Boskoff.

Still, no one wanted to think the worst. Maybe they were lost in the backcountry or pinned down by bad weather. Maybe they’d been arrested and were being held incommunicado. Or perhaps they had decided to extend their trip, as files found on Fowler’s computer clearly indicated interest in a number of peaks in the Eastern Himalaya. But friends were concerned — very concerned. “As soon as I heard that Charlie missed his flight, I was really worried,” said John McCall, an old friend of Fowler’s. “Charlie was too damn cheap to ever voluntarily miss a flight.”

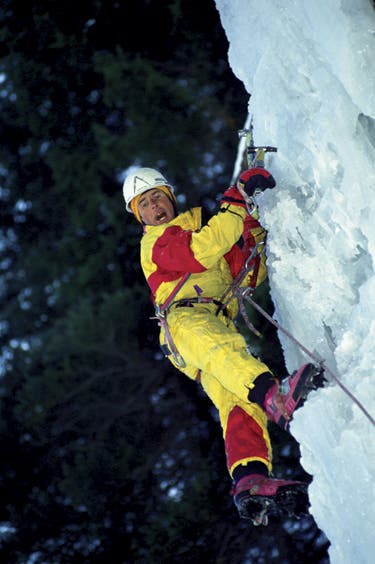

Fowler, 52, was famous for his longevity at the cutting edge of American climbing — in nearly every discipline — and for his uncanny ability to emerge from disasters relatively unscathed. In 1984, he took a 400-foot plunge out of the snowy North Chimney on Longs Peak and came away with nothing more than a bent crampon. And since the 1970s, his bold solo climbs had consistently pushed the envelope. He free soloed the 1,500-foot, ominous The Flakes, in the Black Canyon of the Gunnison, and once went cordless on the 700-foot, overhanging Diving Board, in Eldorado Springs Canyon, in resoled running shoes. In the alpine realm, he made the first ascent of the East Face of Cerro Catedral (VI 5.10 A4+) in Patagonia, in 1992, and his ice and rock accomplishments in the San Juan Mountains and in the Utah desert are too numerous to list. Fowler was also notoriously low-key. For example, when asked about his second-ascent free solo of the IV 5.10- Integral Route on the Diamond of Longs Peak, Fowler supposedly replied, “It was pretty casual,” thus giving the route the name by which it’s known today.

But it also seemed that Fowler was close to using up his nine lives. In 1997, while climbing in Tibet, he and his ropemates took a 1,500-foot fall that left him unable to walk. (During the epic crawl out he sustained serious frostbite, losing most of his toes; he later returned, with little fanfare, to climbing 5.12.) He had, in recent years, split his time between Himalayan expeditions — summiting three 8,000-meter peaks, including Mount Everest — and prolific new-routing around Telluride, Colorado.

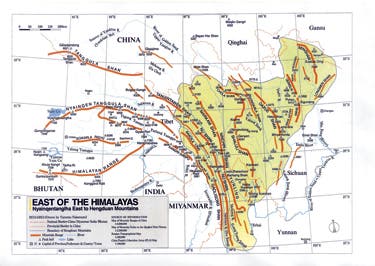

China’s southwestern Sichuan (“Four Rivers”) province is where the Tibetan plateau erupts from the plains of central China. Together with the northern part of Yunnan province to the south, and the Tibet Autonomous Region to the west, the Eastern Himalaya (formerly known as Kham) comprises a vast area with numerous, stunning virgin summits and unexplored valleys. The majority of the inhabitants are ethnically Tibetan — Khampas — and, as Buddhists, consider many of these peaks (including Genyen) sacred.

Fowler and Boskoff decided to climb anyway. Fowler had little patience for China’s ponderous bureaucracy. In an email to Dave Anderson, an American planning to climb in the Genyen valley, Fowler opined that obtaining permits was complicated and expensive, and encouraged “a corrupt system [that] doesn’t help the local people or climbers who will follow in your footsteps” (see sidebar p.71). Without permits, it would be hard to track the pair’s travels.

On December 14, Jon Otto, an American with long experience in the region and owner of a climbing school in Sichuan, dispatched teams of local Chinese climbers to search the towns and trailheads near several unclimbed 6,000-meter peaks of possible interest. Although as focused as possible, this still left a huge search zone — an area the size of Colorado, but twice as mountainous.

Geography wasn’t the only factor. Funding became a formidable hurdle, as well, with a Chinese military aerial search an expensive possibility. Generous individuals fronted enough money to begin the search; however, with an estimated price tag of $75,000, the effort would clearly require fundraising. Accordingly, two committees — one in Telluride and another in Seattle — formed.

After canvassing the towns and trailheads for a week, the four search teams, as well as the police, had produced few leads, merely confirming what was already known: Fowler and Boskoff had been in Litang in early November and had not been seen or heard from since. In order to reach Genyen, Fowler and Boskoff would have driven from Litang to either Lamaya or Zhangna, two tiny villages four hours distant at the road’s end, whence begins the trail to the Lenggu monastery, a 700-year-old complex at the base of Genyen populated by some 200 monks. But the Litang police claimed to have found no trace of them at either village or in talking to the Lenggu monks. Since Fowler and Boskoff had seemingly not visited the Genyen valley, the only remaining clue lay in an email from Fowler in which he wrote, “Now off to one more different area to try a 6,000-meter peak and [a] smaller one.” Wrongly trusting the police’s assertion that they had visited the Genyen valley on December 12 (in fact, they did not visit until December 25), searchers would look elsewhere.

When Gunlogson contacted me on December 12, I was eager to help. Despite living nearby, in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan, and being proficient in Chinese, my reasons for heading to China were mostly personal. I had known Chris for eight years, working under her as a guide at Mountain Madness. One summer, I’d lived in her basement in Seattle; for rent, she charged me a case of microbrew per month. Most recently, we’d guided Mount Elbrus, in the Caucasus. Here, returning late one night from the pub, we’d almost been arrested when police discovered Chris standing on my shoulders, trying to climb onto the roof of the locked guesthouse. Charlie, too, had long been one of my climbing heroes. An old Patagonia ad showed him driving a convertible, fuzzy dice hanging from the windshield, desert rock in the distance, and a beautiful, fit blond climbing in next to him; it convinced me that the life of a traveling climber was all I wanted.

Coming on the heels of the drama on Mount Hood, our search had attracted considerable media attention, and we left Chengdu with a CNN film crew in tow. Two days later, we arrived in 4,019-meter-high Litang, with the CNN folks now suffering from altitude illness and diarrhea. We spent our first day reconnoitering ways that Fowler and Boskoff might have accessed Genyen from the north, rather than via either of the villages to the south. CNN wanted dramatic footage — not just dull images of us going door to door with photos. For a half-hour, we obliged them, donning packs and cold-weather gear and taking a pleasant hike to the top of a small hill a few hours west of Litang. This became the stock footage of the “mountain search” in some of China’s “most rugged terrain.”

Each day brought diminished hope, despite Fowler and Boskoff ’s legendary fortitude. The Telluride search committee had spoken with wilderness medicine experts, and though it was theoretically feasible that they could have survived in the backcountry this long, doubt crept in. Still, the message from the States was very clear: We were to search for live people.

The next day, December 24, after the CNN team departed, we received word that a Litang driver had told police he’d hosted Fowler and Boskoff, had driven them to the trailhead, and had two bags they’d left behind. Initially, the police refused to let us search the bags or speak with the driver, but after the U.S. consulate applied diplomatic pressure, we received permission.

The 700-year-old Lenggu monastery, the last place Fowler and Boskoff were seen alive.Photo by Ted Callahan.

We found Boskoff ’s diary, which revealed plans to start at the village of Zhangna on November 10, and then spend two weeks climbing in the Genyen valley. The driver confirmed that he had dropped them off on November 11, but at Lamaya, not Zhangna, with plans for them to call for a pick-up on November 24. According to him, when that call didn’t come, he thought that maybe they had said December 24. (He was likely “confused” over the date because it’s illegal to run an unlicensed guesthouse.) However, as we’d hoped, the promise of $4,000 had broken his reticence.

That afternoon, we made the four-hour drive from Litang to Lamaya, with a team of 12 searchers, mostly Tibetan trekking guides, as well as the driver. Early on Christmas morning, we set off along the path the driver said he’d last seen the climbers take. As one of the two main trails to the Lenggu monastery, the route was well-used and deeply rutted. We passed three pilgrims heading to Genyen; they’d take a step, drop, fully prostrate themselves, stand up, and then repeat the process. Stopping at every village and nomad encampment to glean info, we spent a day and a half trekking into the monastery, about 900 meters higher and 10 miles from Lamaya. Finally, close to the monastery, we met a herder who recalled a foreign man and woman walking up the Genyen valley about a month previously. He tentatively ID’ed Fowler and Boskoff in a photo.

At Lenggu, we set to work, interviewing the two monks who claimed to have met Fowler and Boskoff on November 13. They showed us where the pair had camped, a short walk above the monastery, and described the pair’s equipment in accurate detail.

Having seen the conditions — the cold, the snow, the avalanche chutes in the valley — we braced for the worst. The monks told us that it had been snowing when Boskoff and Fowler arrived and had continued to snow for three days thereafter, with about six inches total accumulation. This, they mentioned, was enough to set off frequent avalanches on Genyen, the pair’s most likely destination.

Genyen, a glacier-clad giant among a sea of proud rock spires, is the most accessible and striking objective in the valley. Although Genyen had been climbed previously — first by a Japanese team in 1988, and most recently in the spring of 2006 by an Italian team — it had only been done via fairly easy routes, with immense scope for interesting, more direct, 900-meter mixed routes on the steep east face.

Lenggu monastery sits at 4,200 meters, directly below this face, with Genyen’s long summit ridge running parallel along a south-north axis to the main summit, 2,000 meters higher. A flat bench crosses the east face at around 5,200 meters, above which the technical difficulties begin. This bench would have made a great basecamp, but also acts as a catchment for the entire wall, which is crowned by cornices and overhanging seracs.

“A search area the size of Colorado” — a map of Kham with the search area enclosed in black (and Genyen at its bottom). The search headquarters of Chengdu sit near the right edge of the map, below the 31st parallel.Tom Nakamura / East of the Himalayas: To the Alps of Tibet.

By now, any scenario other than a climbing accident seemed unlikely, and any accident would have occurred well over a month earlier. Meanwhile, the monks informed us of very deep snow — more than a meter, in places — farther up the valley, where Fowler had indicated they planned to climb. “But,” said one, “if there is something up there, you will never find it until the snow melts.” That, combined with Fowler’s probable reticence to reveal his plan to climb Genyen, for fear of angering the monks, convinced us to start with Genyen peak and work our way up-valley.

On December 27, five teams of two embarked, with clear instructions that if they found a body they were to establish death, and then leave the site undisturbed. That night, four dejected, tired teams staggered into camp, having found nothing. At 5 p.m., the fifth team descended, declaring, “We found a body.” One member produced digital photos; the climber’s head and torso were buried, though the equipment we could see — boots, crampons, gaiters, and a glove — was modern and Western.

I kept it together long enough to call the consulate and, in Chengdu, Mary, who would inform the committees in the States. Then, I made a plan for the next day’s body recovery, walked over to my tent, and broke down.

That night, it began snowing. Despite the fresh snow, we only needed three hours, walking up a steep moraine to 5,300 meters, to reach the climber the next morning. The body lay directly under the main summit on the aforementioned bench, which showed significant recent avalanche activity; the snowpack over the talus here was extremely unstable. We proceeded cautiously and after an hour of digging, found that it was Fowler. We could see no sign of Boskoff, and the continual snowfall made it too hazardous to continue searching. We were lucky to find Fowler — one day later, his body would have been completely covered by snow. Solemnly, we improvised a litter and carried him down. Over the next few days, we conducted the grim business of transporting his remains back to the nearest mortuary, where Charles Duncan Fowler was cremated on New Year’s Day 2007.

Our best guess is that Christine Boskoff and Charlie Fowler died sometime between November 13 and 22. If it was snowing when they arrived, they probably wouldn’t have gone right for Genyen, opting instead for a rock climb on one of the spires. Regardless, at some point they hiked up from the main trail and along the moraine to reach the bench. Above it, they could have accessed a fairly narrow snow gully, bounded on both sides by rock buttresses. The gully, about 30 feet wide and pitched at 50 degrees, stretched 500 meters above the bench. If they had climbed up a couple hundred meters, they could have set up camp in the relative shelter of the right-hand buttress, positioning themselves for a quick blast to the top. Above there, a rightward-traversing ramp led to the blocky north ridge to the summit. It would have been a logical, direct, and relatively safe line… except for the gully, which widened at the top and acted as a massive funnel.

Genyen’s east face, with the bench where Fowler’s body was found indicated by the red dot. The pair’s prospective route up the gully, then north ridge, follows the red line.Photo by Ashley Pollack.

Fowler’s body lay in the fall line below this gully, 100 meters above the bench, and showed trauma consistent with a long fall. He was lightly dressed, with a fleece jacket tied around his waist. In the lid of his pack he carried his sunglasses case — empty — and wool hat, so it must have been daytime and fairly warm. The pack held a sleeping bag, some extra clothes, a stove and liter of fuel, three to four days of food, a cooking pot, enough webbing to improvise a harness, and a coiled rope. It was clear that he wasn’t climbing so much as moving camp when he was killed. Boskoff was probably carrying the climbing hardware and tent, plus her own gear. On Yala and Jampalyang, both lower than Genyen, they had set up advanced basecamps at around 5,200 meters, from which they could summit in a long day. It seems clear that this was their plan on Genyen, as well, and that whatever killed them — avalanche, ice fall, cornice collapse from above — hit as they headed up the gully toward their intended camp.

We may never know what happened. For alpinists of Boskoff and Fowler’s caliber, the gully would have been simple, and the lack of climbing hardwear, including a harness or rope, on Fowler’s body attests to this. It also seems impossible that Fowler might have died in the accident and Boskoff, if left alive, could not have gotten down to the monastery, an easy hour away. (She even could have crawled if injured, as the terrain is non-technical.) Most likely, they were just in the wrong place at the wrong time, and a freak accident — one that could have happened to anyone — claimed their lives.

Christine Boskoff still lies somewhere below Genyen’s summit. There is hope that when the search resumes in the spring, when the winter snows begin to melt, we will bring her home. We know that Charlie Fowler never would have wanted to leave her. If we can’t find Chris, Charlie’s family has asked us to scatter some of his ashes up there, so that they can remain together forever, overlooking the infinitely lovely Genyen valley.

Genyen’s east face.Photo by Ashley Pollack.

The Permit Conundrum Most formerly restricted areas in the Eastern Himalaya are now open to tourists, including many peaks sacred to the locals. While local and international opposition to climbing such objectives remains strong, according to the Sichuan-based climber Jon Otto, “The mountaineering associations will issue a permit to climb virtually any, if not all, the peaks in Sichuan… once the money hits the table, I would bet anything still goes.” And, as Fowler noted, “It’s all a big scam, with different mountaineering associations competing to issue permits and rip off climbers.” The alpinist Dave Anderson, for example, recalls one Chinese guide quoting him a fee of $1,500 to climb virgin peaks in the Genyen valley, and another adding the spurious charge of $1.50 per person per night as a “grassland sauce protection fee.” In most cases, permit money ends up in the pockets of corrupt Chinese officials.

On Genyen, Fowler and Boskoff likely felt that since the Chinese officials were going to grant permission for these sacred peaks anyway, they might as well be the ones to climb them, “doing it on [their] own and hiring local people,” in Fowler’s words. With Genyen, they probably figured that the previous ascents had diluted local opposition to climbing. It was telling that the parties most upset during the search were the local mountaineering associations, who had missed out on collecting lucrative fees, and not the Lenggu monks. Still, given that the Chinese allow climbers on even the most sacred peaks, it is up to the individual to decide whether to climb or not.