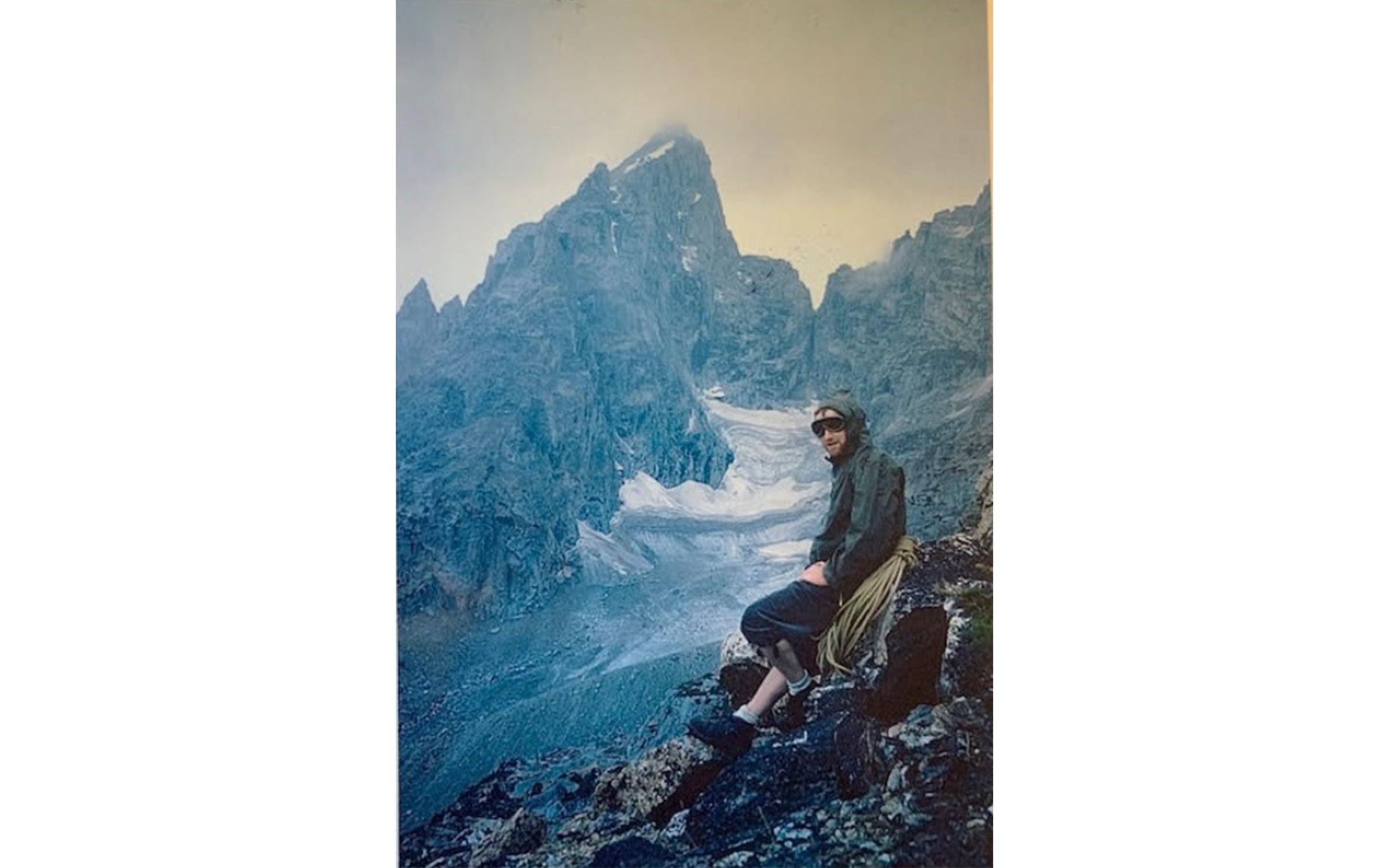

A Climber We Lost: Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, October 10

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. (Photo: Csikszentmihalyi family)

You can read the full tribute to Climbers We Lost in 2021 here.

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, PhD

87, October 10

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi was a pioneer in the field of positive psychology, best known for his research and findings in the state of consciousness he called “flow.” He considered rock climbing a perfect conduit for experiencing flow, and was a climber himself.

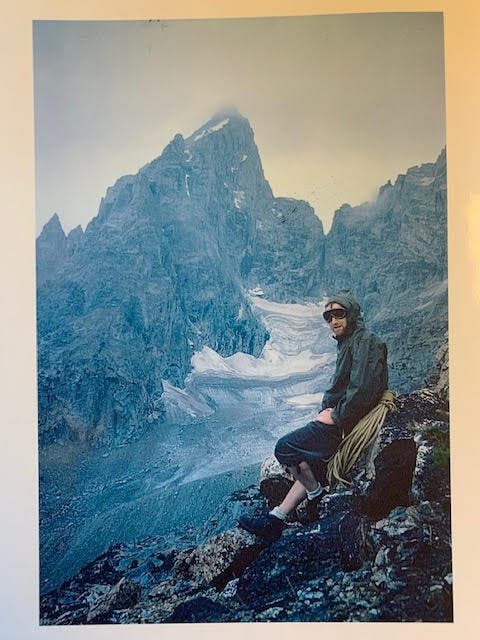

Hungarian by descent, the young Mihaly grew up in Italy during the sad and chaotic time of World War II, with his family separated, one brother killed, and another put in a labor camp. As an adolescent living in a post-war refugee camp in Italy, according to the Washington Post, he “played chess with adults, becoming so engrossed in the game that he forgot about his troubles. He later found the same sense of inner accomplishment—a feeling he would recognize as flow—from rock climbing and painting.”

Dr. Csikszentmihalyi told the Edge.org: “We moved to Italy at the end of the war, and I got involved with the Boy Scouts and other youth organizations. As a result, I started mountain climbing and rock climbing in the Dolomites in northern Italy. Climbing produced the same kind of result of total concentration, a feeling that you were doing everything you could, that your whole being was involved, and that you forgot everything else. And at the time there was a lot that you wanted to forget.”

His son Christopher posted on Facebook: “As a refugee in postwar Rome, he attended the Classical Gymnasium ‘Torquato Tasso,’ was an avid rock climber, and waited tables …. His own experiences of enjoyable concentration in rock climbing, chess and painting were largely ignored in psychology and psychotherapy, which were at one time largely anchored in the analysis of negative pathologies. He introduced a framework for the study of these positive states.” From his studies arose the 1975 book Beyond Boredom and Anxiety, eventually followed by the bestselling Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience, in 1990.

A breakthrough in Csikszentmihalyi’s young life occurred in 1951, when he was staying in the Swiss Alps, exploring the mountains and trying to work at a ski resort—but broke, as there was no snow. He randomly attended a free lecture that turned out to be given by Carl Jung! Csikszentmihalyi became an enthusiastic reader of psychology texts and soon after came to the United States to study it, earning his doctorate in 1965 from the University of Chicago and teaching there for many years, and then at Claremont Graduate University.

Many climbers I know have appreciated the book Flow, for describing a familiar state. I was exposed to Csikszentmihalyi’s work through Virginia Savage at the 1989 climbing World Cup at Snowbird, Utah. Virginia, a doctoral candidate in sports psychology, had been contracted by the U.S. Olympic Committee to study the competitors who were willing to be interviewed. I was one, and soon after she mailed me copies of a number of Dr. Csikszentmihalyi’s writings on the state of flow. We collaborated in developing programs for CityRock, a climbing gym I opened at the time in Emeryville, California, and I eagerly read Flow when it came out. Today, at the Gateway Mountain Center, a non-profit in Truckee, California, we use flow science in our work with children suffering from serious emotional disturbance and complex trauma. We use climbing as we can, and also seek terrain such as logs across creeks and talus fields to cross to support youth in accessing the optimal zone of challenge. These efforts can help them experience relief from depressive and anxious thoughts, while building pathways of resilience.

Dr. Csikszentmihalyi wrote in Flow: “The mystique of rock climbing is climbing; you get to the top of a rock glad it’s over but really wish it would go on forever. The justification of climbing is climbing.”

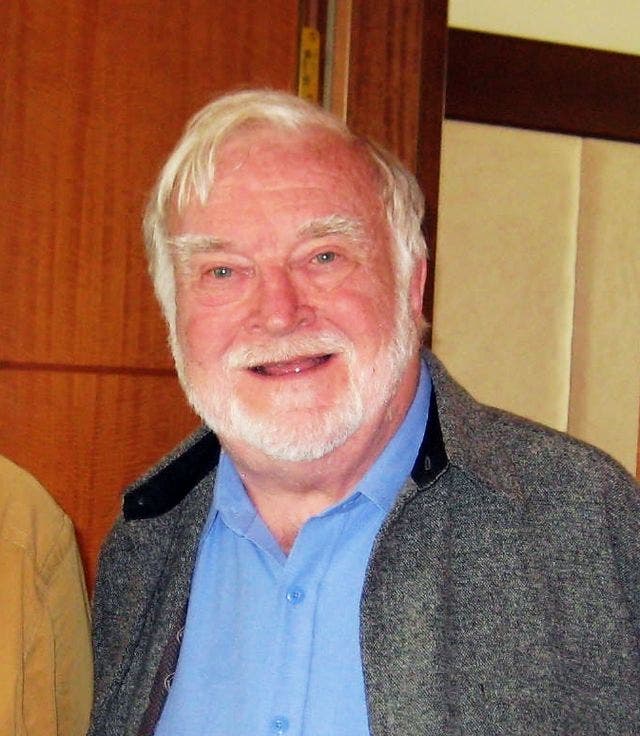

After a period of declining health, he died at home in Claremont, California, leaving a wife, Isabella, and two adult sons, Chris and Mark. Chris marveled at his father’s grace throughout, saying, “He was an incredible gentleman until the last breath.”

See also this obituary in the New York Times.

You can read the full tribute to Climbers We Lost in 2021 here.