Alaska Requiem: A Friend's Death and a Lifetime of Weighing the Cost

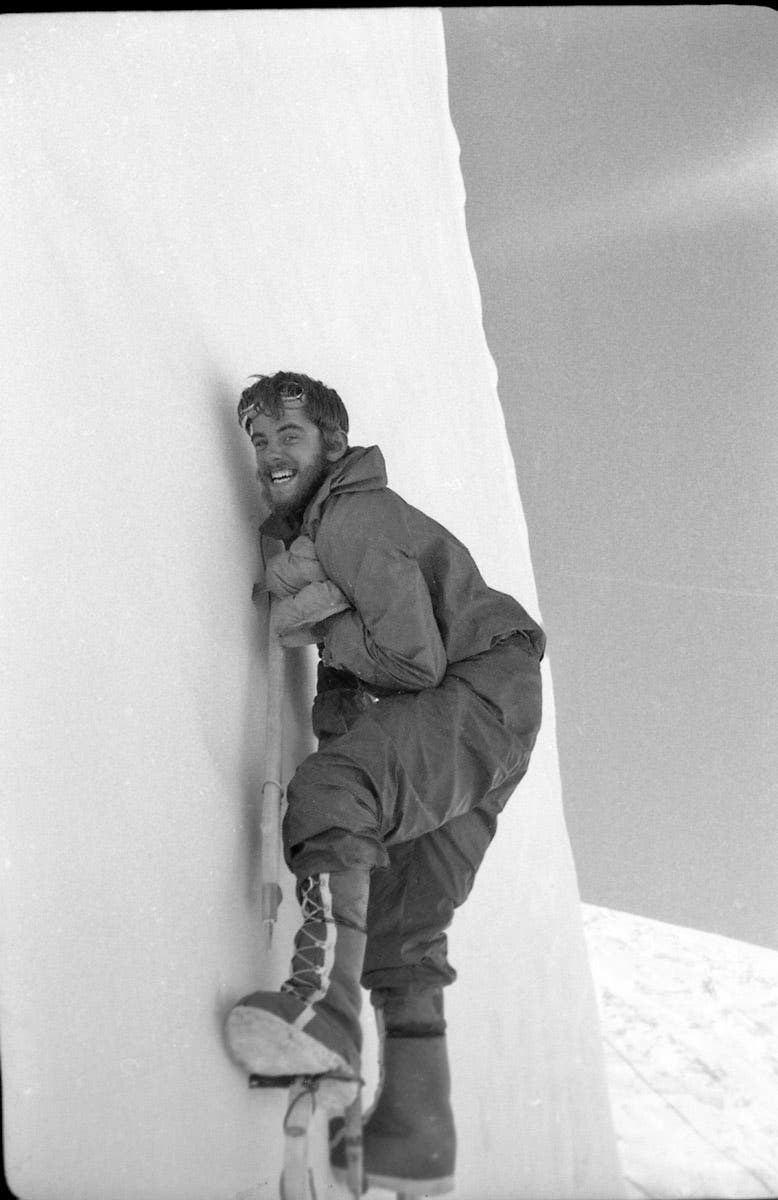

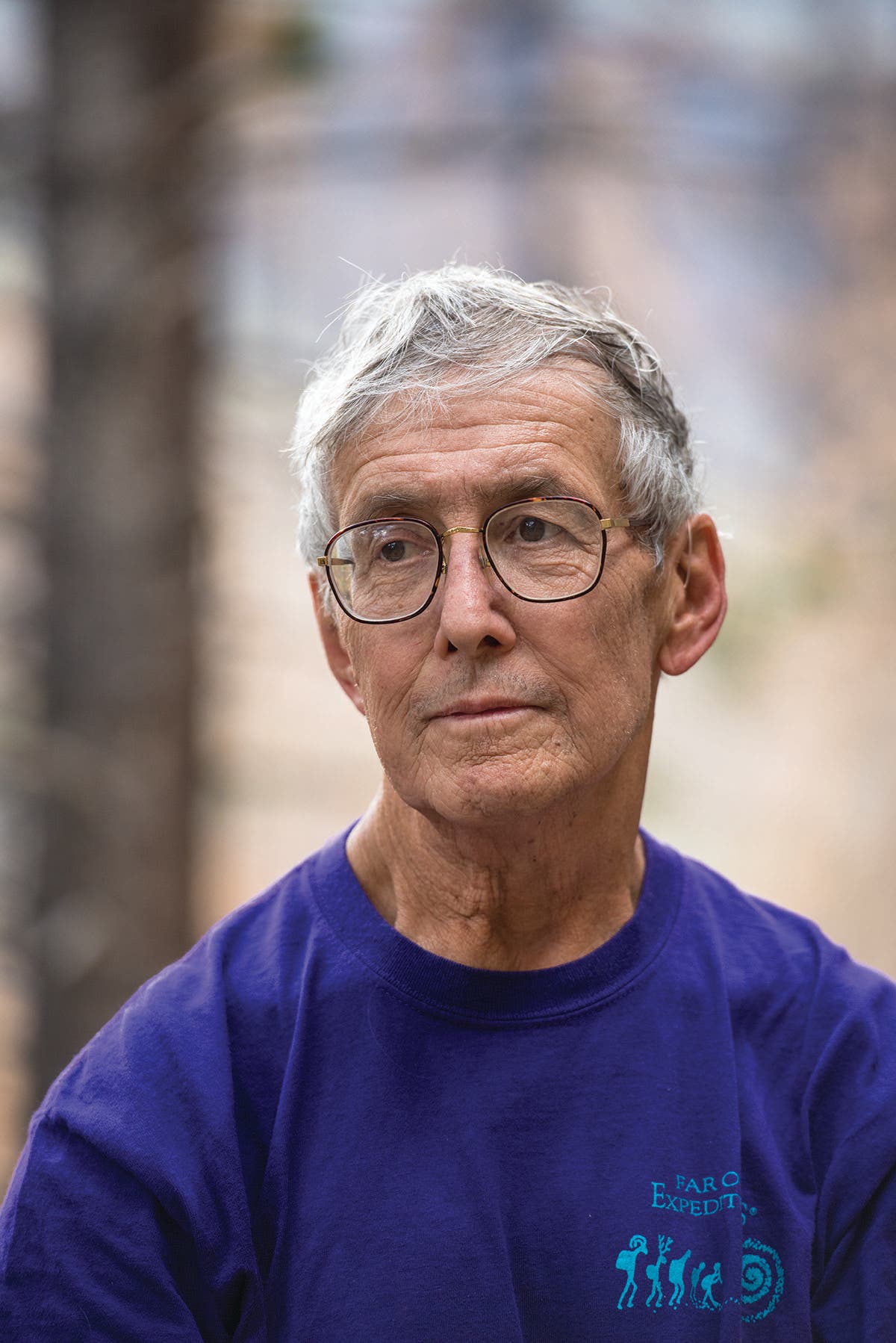

Rick Millikan atop the Icebox—key to the upper Wickersham Wall, during the first ascent in 1963. (Photo: John Graham)

We took turns driving the VW Microbus, riding shotgun, or lying in back in a jumble of ropes, hardware, food boxes, and Ensolite pads as we tried to sleep. Outside, the dreary landscape plodded by at 30 miles an hour: jungles of birch and dwarf spruce, lagoons infested with ferns and tussocks. In the muddy truck-stop parking lots we piled out to buy burgers and coffee, the smell of bacon grease and stale fries wafting across the lunch counter, windows shut tight against the emptiness. Those truck stops broke the 1,200-mile book of unpaved Alaska Highway into chapters: Trutch, Wonowon, Toad River, Muncho Lake, Jake’s Corner … And for punctuation marks, the red roadside crosses: “Three died here 1953.”

I was afraid. As I lay in back, hiding under a sleeping bag, the engine drone a bass thrum in my head, I tried to dissect my fear. Of the mountain, of course, in all its hugeness. Of what I had agreed to do, after Rick and Hank had invited me up to Rick’s college dorm room and casually popped the question: “We’re thinking of climbing McKinley this summer. Wanna go?” Of the wild Northland this desolate trail was unfolding. Of the prospect of spending more than a month on glaciers, in storms, under seracs and rock walls. Of commitment. Of the unknown.

The summer before, I had worked construction in my hometown of Boulder. In these addled spells inside the hurtling Microbus, I might well have traded the prospect of the Wickersham Wall for a return to hefting two-by-fours and prying out bent nails. But the seniors in the Harvard Mountaineering Club were demi-gods. Rick and Chris had climbed Waddington, Hank had already been on another route on McKinley (renamed Denali, its original Athabaskan name, in 2015). What did I hope to become, if not their peer? In any event, there was no backing out now.

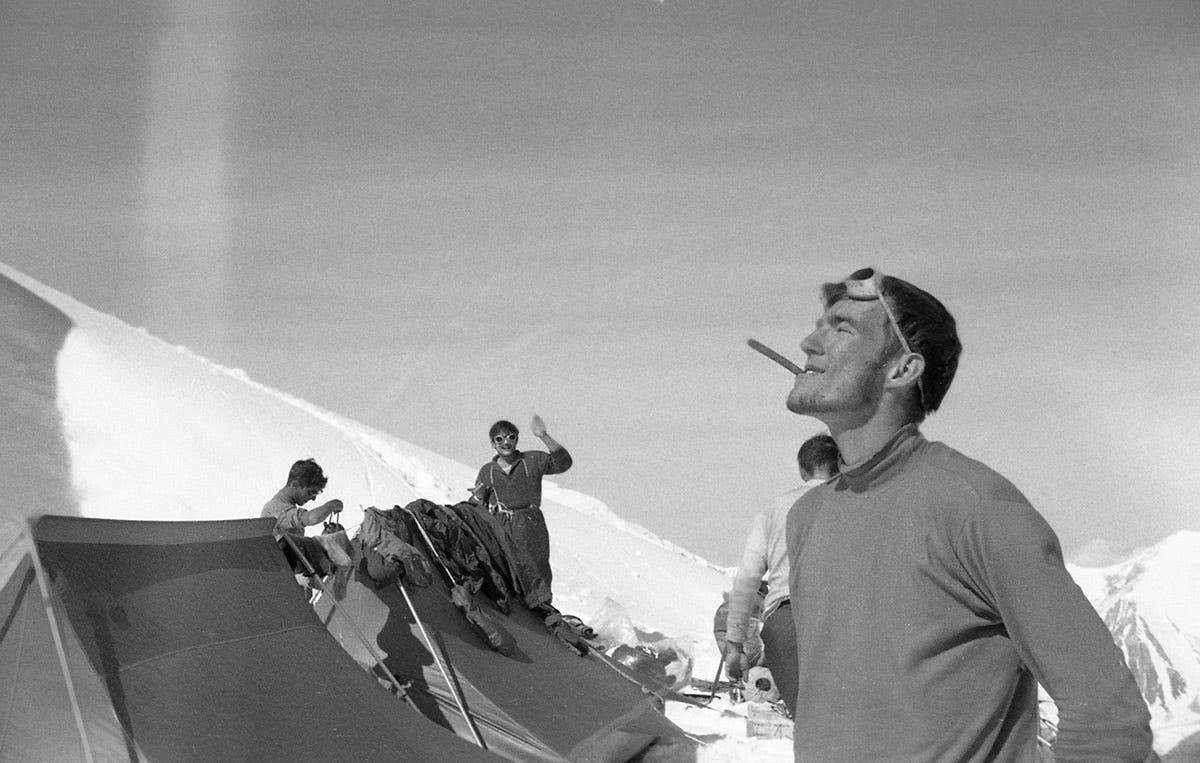

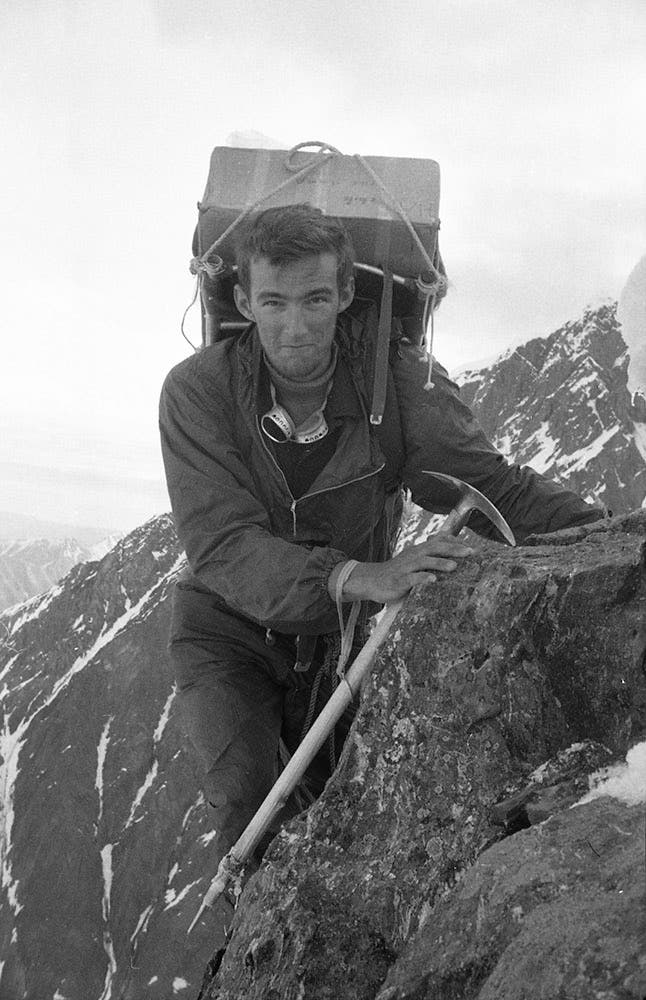

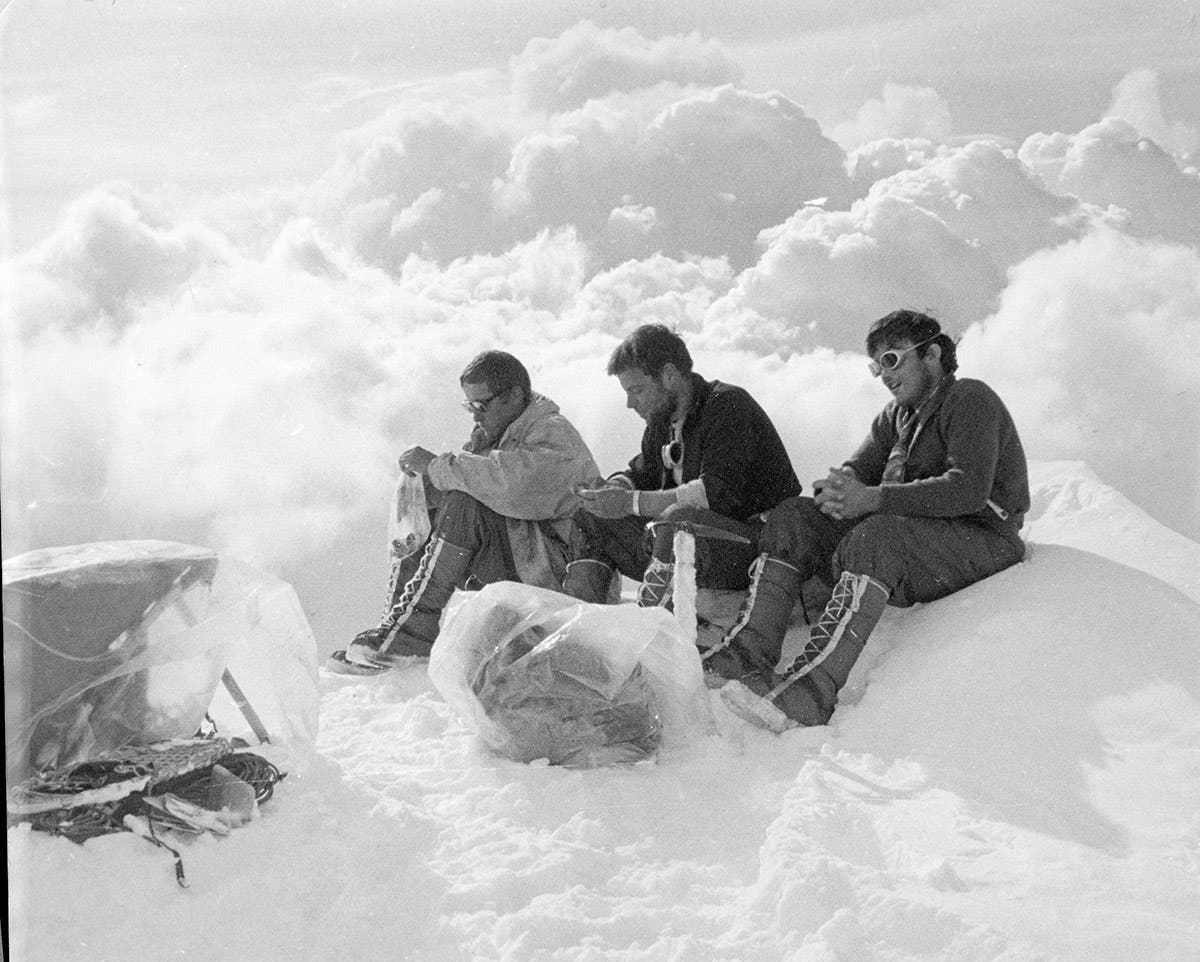

Two weeks later, in tents pitched at the head of the icefall leading to the crux rock buttress on the unclimbed 14,000-foot face, seven us—Rick Millikan, Pete Carman, Chris Goetze, Hank Abrons, John Graham, Don Jensen, and I—were camped in a shooting gallery. In my diary, I blandly noted, “It seems quite hazardous, and already two falling rocks have put holes in our tents, and a few big ones have just missed … About an hour ago a slide swept just to the west of camp, right over the ends of the rope on which we had been hauling.” Yeah, it was scary, but I wasn’t scared. This was what big-range mountaineering was all about.

After we got up the Wickersham Wall in 1963, among my six partners, one never climbed in Alaska again. Three ventured forth on a single second effort each in the Great Land, one other on two further expeditions. Don Jensen would end up assaulting Alaskan peaks on four long exploits, two of them failures on Mount Deborah. But I came back again and again, until I had notched 13 forays up North. Alaska had set its hook in my soul.

That April day in Rick’s dorm room, there was no way I could say no to him and Hank. Two years later, there would be no way Ed Bernd, a sophomore as I had been in 1963, could say no to Mount Huntington. In 1965 in our high camp, exhausted and giddy after gaining the summit on the 32nd day of our struggle, crammed four into a two-man tent, I said, “Man, that was the best climbing day of my life!” Ed answered, “Mine, too. But I’m not sure I’d do it all over again.”

Seven hours later, he was dead.

And 56 years later, guilt still gnaws holes in my well-being.

When I was in my twenties and early thirties, Alaska seemed a land of limitless promise, of unnamed peaks and barely explored ranges: the Great Gorge, the Hayes Range, the Kichatnas, the Revelations (where no one before us had ever been), and, way up beyond the Arctic Circle, Igikpak and the Arrigetch. During the school year—Harvard, grad school at the University of Denver, then teaching at Hampshire College—nine months of desk-bound servitude served as the penance I paid for another pilgrimage into the heart of the great mystery, the eternal wonder of couloir and buttress untouched by human hand or foot.

But to get to the mountains, you had to drive that gloomy haul road through Trutch and Wonowon, fill the gas tank at Tok or Delta Junction, then waste the precious summer daylight buying food for 40 days in Fairbanks or Anchorage. Talkeetna I could like: the ten-buck breakfast at the Roadhouse, where Carroll and Verna Close filled your plate with more pancakes and bacon than three sourdoughs could eat; beers at the Fairview Inn, the walls hung with fading portraits of old miners and dead pilots; Don Sheldon’s cavernous hangar, where we packed and waited nervously for the flight in; the B & K trading post, where Sheldon and Cliff Hudson once broke the candy case in a legendary fistfight.

Out of the truck, legs spread, hands on hood, we were frisked down, the nervous younger cop’s hand on his holstered pistol throughout.

But the Alaska of its towns and two real cities seemed to flaunt its tawdry boosterism, its ramshackle post-frontier sprawl. I got my first good dose of it in the summer of 1966. Still shaken by Ed’s death on Huntington the previous July, I wasn’t at all sure I was ready for another expedition. But Art Davidson, who lived in Anchorage in his truck (named Bucephalus, after Alexander’s horse), was imploring me to join him in the Kichatnas—a range Don Jensen and I had actually planned to investigate a week or two after Huntington, until the loss of Ed changed everything.

Out of the blue in May, 1966, Art had phoned me in Denver to say that a cushy summer teaching job at Elmendorf Air Force Base had suddenly come open, after the longtime instructor had mysteriously defected. I’d never taught anything: It would be two more years before my profs at the University of Denver unleashed me on Freshman English. But I got the Elmendorf job, and flew to Anchorage as soon as DU’s spring term ended. My god, the pay was $2,700—enough to fund three years of expeditions! Art and I put off the Kichatnas until September.

That spring I’d started dating Sharon Morris, a fellow student in a DU creative-writing class. We’d only begun to get to know each other, but on impulse I invited her to fly up to Alaska and share the summer with me. On impulse she agreed.

It was the first time either of us had shacked up with a lover. “Shacked” is the right verb for the one-room plywood box we rented in Spenard, then Anchorage’s slum. It didn’t even have a separate bathroom: instead, a phone-booth-sized cubicle carved out of an interior corner, next to the lumpy, narrow double bed.

My gig at Elmendorf was back-to-back two-hour classes in basic grammar and modern fiction from 6:30 to 10:30 Monday through Thursday evenings. Sharon snagged a job in the sewing department of JCPenney. Our schedules at once got out of whack. After teaching for four hours, I was too wired to sleep until 2:00 or 3:00 a.m., and Sharon got up at 7:00 to take the bus to Penney’s.

I walked into my first classes with trepidation. At 23, I looked even younger, and I’d be teaching G.I.s twice my age. On the fiction reading list was Catch-22. The prospect of deeply offending the men and the service that Joseph Heller so ferociously lampooned filled me with dread. But the men in my night class wept with laughter as they rehashed Yossarian’s wildest riffs: “He’s got it down perfect,” they raved over that misfit’s shenanigans. It turned out I was a hit as a teacher. My students even got a kick out of diagramming sentences.

Some of the time, Art lent me Bucephalus to commute from Spenard to Elmendorf, and many a late evening we cruised around town talking climbing and the Kichatnas. That summer he’d sneaked through a window at Alaska Methodist University to play a basement piano for fun. An APB must have gone out on him, for one dim midnight a pair of squad cars, lights flashing, blocked us in. Out of the truck, legs spread, hands on hood, we were frisked down, the nervous younger cop’s hand on his holstered pistol throughout. The next morning I bailed Art out of jail.

I caught his 45-foot fall on a hip belay, carving deep grooves in my fingers.

On weekends I headed off to the Chugach (or “Chew-Jacks,” as the local climbers called it), southeast of town, for alder-whacking and ridge-scrambling on rotten rock in Alaska’s ugliest range. I was out of shape, and the Kichatnas, I knew, would be a stern school.

Some Friday or Saturday nights, all three of us hit the strip joints, which were female-friendly in the gold-rush tradition. Sharon was shocked by the whimsical lewdness of the dancers: one of them had a trick of twirling banners attached to her nipples in opposite directions while she talked Mae-West-dirty to us gawkers. But other nights when the sky was clear we elevatored to the top-floor bar at the Captain Cook, where we sipped Manhattans. Through the panoramic windows, far off to the northwest, we could glimpse the upper spires of the Kichatnas, backlit at midnight. “We’ll be there in only five weeks!” Art would peal.

Yet Anchorage, ensconced in one of the loveliest natural settings in Alaska, between the tidal rips of Cook Inlet and tundra-swathed foothills, depressed me. Fourth Avenue was asprawl with derelicts and drunks, most of them natives. The fast-food chains were the same as in the Lower 48, only twice as expensive. I got food poisoning from potato salad at the Safeway lunch counter.

I never thought I’d fuss like a mother over younger friends obsessed with mountains as I once was.

The Alaska Book Cache was a haven for misfits in a town where few read the Daily News, and the New York Times was unknown. One rainy evening in Bucephalus, Sharon and I passed a big native man with a bloody bandage over his right eye, trying to hitch to the hospital. I started to pull over, but Sharon yelled, “No!” We drove on, nursing a nasty argument about racism versus safety. In the so-called “faculty room” at Elmendorf, sipping stale coffee, I listened to my colleagues trading tips about real-estate deals and the prospects for a bonanza drilling oil up by Prudhoe Bay. Ever since Nome in 1899, Alaska had been the locus classicus of get-rich-quick every-man-for-himself. You could smell the greed in the Anchorage air, damping the sweet, sorrowful scent of fireweed and willow.

Even though I climbed in Alaska 13 years in a row, I never wanted to live in the 49th state. The students at Hampshire who came under the sway of my Alaska passion wondered why not. Several of them moved to Alaska for good, including two fine writers, Tom Kizzia and Nancy Lord.

One reason for me at first was that the technical standards in Alaska were woefully low. From my base in Massachusetts, I had the Gunks, Cannon, Cathedral and Whitehorse, also the ice gullies in Huntington Ravine, on which to hone my skills. Anchorage climbers had what?—the grungy seaside scarps on the Seward Highway. The denizens of Fairbanks and the U. of Alaska had even less.

All that would be remedied in the next generation, though, with the discovery of Valdez ice and the emergence of brilliant alpinists such as Andy Embick, Carl Tobin, and Roman Dial.

My dismay about Alaska culture was not confined to the shopping malls of Anchorage and Fairbanks. On later visits to the towns of Barrow, Nome, Shishmareff, and Allakaket, I saw the tragedy of Inuit assimilation at its grimmest.

The ravages of the “native problem” had their roots in the gold-rush mentality, in the quintessentially American contempt for the poor and marginalized. The other two countries with large Inuit populations, Canada and Greenland (long a Danish colony), had handled the cultural clash with far greater wisdom—especially the Danes in Greenland, who enforced rigid prohibitions to keep visitors from corrupting Inuit life. But booze, drugs, and third-class status were built in to native Alaska from Nome in 1899 on.

My last northern expedition came in 1975, when I triple-packed into the Tombstone Range in the Yukon with two Hampshire students, Mark Fagan and Jon Krakauer. We were proud of our bare-bones style, with no airdrop, no radio, and a hitchhike down the Dempster Highway to Dawson City at the end rather than an arranged pickup. But the only previous party’s promise of “Bugaboo-style granite” met the reality of crappy rock and avalanching couloirs, and June was too early in the summer.

On the east face of Little Tombstone, Jon and I climbed a thousand feet through minor volleys of falling rock and salvos of collapsing snow and ice. Jon’s lead on the fifth pitch was a delicate A4 dance on tied-off knifeblade tips. We climbed through the night, and suddenly I was only 60 feet below the summit, where the wall leaned back from vertical to 65 degrees. Piece of cake, I thought—until I saw the trap. No cracks, no pro, and every hold was brittle. From a four-pin hanging belay I watched Jon inch skyward. A foothold broke; Jon cursed, then slid, bounced, and plummeted into the air below me. In the age before GriGris or ATCs I caught his 45-foot fall on a hip belay, grinding my brake hand into the cliff, carving deep grooves in the backs of my fingers.

We rapped the wall, exhausted, over-careful, and bummed out, and finally collapsed on the grass, glad to be alive. Jon was animated by our close call, but we’d blown through our hardware building rappel anchors on the retreat, and the rest of the trip we could get up only easy peaks while we rationed our dwindling food supply.

A month later, with Nate Zinsser and Tom Davies, Jon put up the Ham and Eggs route on the second ascent of the Mooses Tooth. The line is now the most sought-after classic in the Ruth Gorge.

I didn’t make a conscious decision to quit expeditioneering, but the close call on Little Tombstone haunted me. So did other close calls on my 12 previous forays, the death of Ed Bernd, and the slow-won recognition that there’s no such thing as safe climbing in Alaska. And the many days stuck in storm-lashed tents when I wondered what other adventures I was missing by lurking in ambush of nameless peaks.

I’ve kept climbing the rest of my life, in ranges like the Dolomites and Wind Rivers, on crags all over North America and Europe. But it wasn’t the same, and I knew it. I returned to Alaska, on four wonderful fishing trips with my father to remote lakes in the Brooks Range, on magazine assignments, and one January as, at Roman Dial’s invitation, I guest-taught a class at Alaska Pacific University in—what else?—the literature of Alaska.

But nothing filled the void I had left behind after the Tombstones … until, almost 20 years later, I discovered the joys of hiking the canyons of the Southwest in quest of prehistoric ruins and rock art. It wasn’t life and death, and it wasn’t about triumph or failure. But searching for the Old Ones has centered my life for about the last 30 years. I got hooked in 1992, and I like to think that the tamer adventures of this quest range into realms beyond the scope of mountaineering—among them, the challenge of understanding how another people in another time comprehended the world. A single arrowhead lying in the dirt poses questions no direttissima can answer.

While I dabbled with easy routes on local crags, I’ve kept up an intense interest in what younger, bolder climbers were doing in the great ranges. I pored over each issue of the AAJ. When I read accounts of new routes in Patagonia or East Greenland or the Karakoram, I kicked myself that my focus on Alaska had precluded voyages to those magic lands.

The older I got, and the more my physical capacities declined—especially during the last six years, under treatment for incurable cancer—the more the Alaska of my youth seemed to lie beyond a veil, a lost paradise of unfinished business.

And then I discovered that, thanks as much to my writing as to my Alaskan campaigns, I had become not the old fart relegated to history that I expected, but a pioneer, even a mentor. Michael Wejchert is the son of Chris, one of my later-life climbing pals. As a teenager Michael grew ambitious, but all of a sudden he seemed to graduate from Cathedral Ledge to the Alaska Range. I learned only indirectly that he was fixated on Mount Deborah because as a kid he had read my book about Don Jensen’s and my attempt on the east ridge in 1964. In the last 50 years, Deborah has seen only a handful of ascents. Michael decided to go after its finest and most challenging route, the 4,500-foot south face, which had never been climbed nor even attempted.

Don Jensen had first seen it from the air, as he flew with our pilot to deliver our base-camp airdrop. As soon as he got back, he told me, “We’re in for something incredible, Dave!” I first encountered the face suddenly, as we crested a low pass on the fourth day of our 40-mile hike-in. I wrote in my diary, “Descriptions fail. It is going to be tough.”

I’ve climbed with Michael at Mammoth Lakes, Skaha, and Cathedral and Whitehorse, on chummy outings of our self-styled Old Gang, founded in 1996 by Matt Hale, Ed Ward, Jon Krakauer, Chris Wejchert, Chris Gulick, and myself. Michael’s skill and grace on rock, his focused judgment, are a wonder to see. But Alaska doesn’t care about skill and grace. His father, Chris, and I agonized quietly when Michael went off in April 2013 and again in April 2015 to do battle with (to appropriate Don Jensen’s malediction) “the black heart of that monster.”

The first April, extreme cold—a steady minus 40 degrees—shut down Michael’s team before they could really come to grips with the south face. During the second April, the pilot’s being forced to land far from the face, together with a month of nonstop storms, dictated another retreat. Since then, Michael has climbed in the Ruth Gorge and made a marathon traverse of the Denali massif with Freddie Wilkinson and Dana Drummond. But the south face of Deborah is in his head, promising the old illusion of transcendence that mountains always tease.

That evening, I told Clint and Jess, “You guys should have won the Piolet d’Or. But Alaska isn’t on the judges’ radar.” Eighteen months later, Jess was dead, avalanched off Howse Peak with David Lama and Hansjörg Auer.

For years after our 1967 expedition—five of us from Harvard and Art Davidson—that made the first ascents in the Revelation Mountains and named the range, I wondered why others hadn’t swarmed to its limitless prospects, as climbers had to the Kichatnas after 1964. In print I’d taunted the future by singling out what we considered the hardest peak in our branch of the range (Golgotha) and by singing the praises of a peak (Mausolus) I saw only on the flight in, and which I thought might be the hardest of all to get up. Then along came Clint Helander.

By the time of this writing, Clint’s not only knocked off Mausolus and Golgotha, but in a dozen expeditions to the Revs, he’s climbed and named other great peaks, while surviving more close calls than I ever did. We corresponded, then met. I couldn’t believe how modest a fellow he was, and how much respect he showered on those who came before—including me. In 2015, Matt Hale and I headed up to Alaska to give our slide show on the 50th anniversary of climbing the west face of Mt. Huntington. We feared that nobody would care, that few would show up. But in Anchorage and Talkeetna, we met raucous, cheering audiences. It was Clint who organized everything, designed and put up the posters, then squired us around for beers here and strolls there as if we were ambassadors from important countries.

In 2017, Clint and Jess Roskelley pulled off the first ascent of the massively long, five-towered south ridge of Huntington, one of the greatest deeds ever accomplished in Alaska’s mountains. When I first saw Brad Washburn’s photos of the south ridge in 1965, I drew a sharp breath as I thought, That’s a route for the next generation. Or the next.

On the ridge, as clouds and snow enveloped the two men, Jess kept nervously asking, “Is this just a local storm? Or a major one?” Clint, as he later told me, bluffed confidence. By the third day, the two men were truly—in that old exploration cliché that so seldom earns its keep—past the point of no return. A place where I had never been.

I agonized over Clint and Jess when they were on the climb, out of contact. So did Michael, who had been slated to pair with Clint until a shoulder injury put him hors de combat.

Clint called us both from the summit with his cell phone batteries fading. And six months later, Sharon and I shared a single evening with Clint and Jess in Telluride, where they were working a construction gig to feed the rat of their climbing addiction. Jess at first addressed me as “Mr. Roberts.” I told him that I’d met him when he was two, when I interviewed his dad for Outside magazine.

That evening, I told Clint and Jess, “You guys should have won the Piolet d’Or. But Alaska isn’t on the judges’ radar.” Eighteen months later, Jess was dead, avalanched off Howse Peak with David Lama and Hansjörg Auer.

I never thought I’d fuss like a mother over younger friends obsessed with mountains as I once was. I don’t think Brad Washburn, who talked us into the Wickersham Wall, promising it would be a safe route, worried about us on McKinley. When we were reported missing and feared dead, Brad told the papers, “Nonsense. Five days out of touch is nothing. Those boys know what they’re doing.”

Michael Wejchert and Clint Helander know what they’re doing. But so did Jess Roskelley. And Hayden Kennedy, and Marc-André Leclerc, and Kyle Dempster, and so many others among the world’s best alpinists.

If Clint or Michael were killed in the mountains, not only would I be devastated, but it would in some sense call into question my faith that, after all, climbing is huge and ennobling and worth risking everything for, rather than crazy and stupid and tragic. When Clint got back from his latest foray into the Revelations, after another pair of near misses, I sent him a jaunty e-mail—something like, “Whew. Hope you can dial it back a little now.”

But what my heart says every time they go off is that old, useless plea: Be careful. It’s what my mother told me as we drove out of Boulder in June 1965 on the way to Huntington. It’s the last words Ed Bernd’s mother ever said to him.

This article was first published in Ascent in 2021.

Read More:

- “The Big Maybe: Revisiting David Roberts’ The Mountain of My Fear” by Jeff Jackson

- “Remembering David Roberts” by Duane Raleigh

David Roberts (1943-2021) survived 13 Alaskan expeditions. He is the author of numerous classic pieces of climbing literature, including Mountain of My Fear, Deborah, and On the Ridge Between Life and Death: A Climbing Life Reexamined. His final book, published in 2021, was The Bears Ears: A Human History of America’s Most Endangered Wilderness.