10 Million People Watched The Dru Rescue. The Media Created Heroes And Villains.

A stunned Hermann Schriddel safely off the Dru, facing the media spectacle. (Photo: Gerard Gery/Paris Match (via Getty Images))

At 3 O’clock in the morning of August 19, 1966, six men crept up the Mer de Glace, the glacier from which the Petit Dru spits upwards. In the dark they could not see the mountain before them. Rain spat down, soaking the climbers to the bone. Ropes, pitons, army rations and sleeping bags bulged out from their heavy rucksacks. They plodded up in the dark: an American, two Germans, an Englishman, two Frenchmen. Some had met for the first time the previous night, in the smoke and gloom of the Hotel de Paris, the cheapest place for an itinerant climber to cop an actual bed in Chamonix. Above the six men was a mountain face that, 15 years earlier, had not once been climbed.

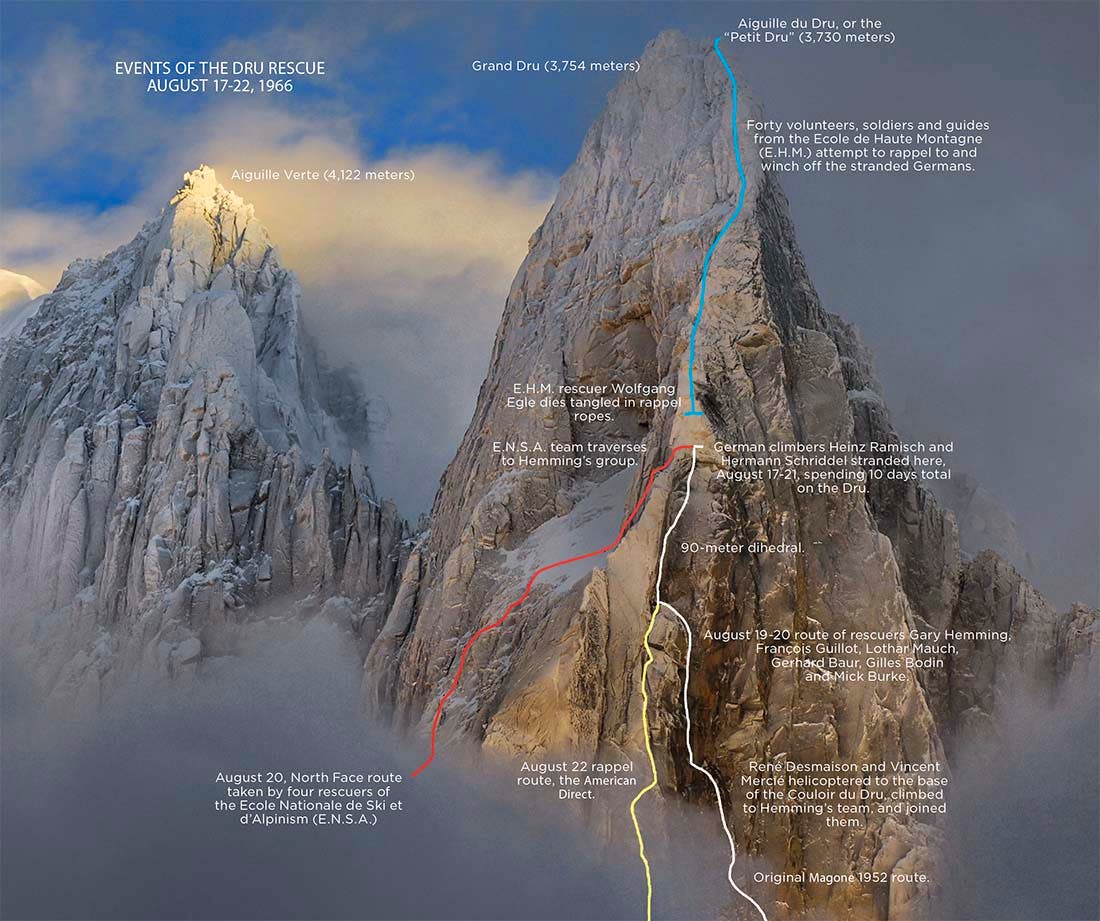

But the six men were not assembled to climb the Petit Dru—they were to save two young Germans who were ensnared on a ledge, unable to retreat, and unable to continue climbing. Verglas coated the entire wall. A helicopter had flown over the mountain on the 17th, and spotted the Germans through the clouds. They were alive. Forty rescuers had been dispatched to the summit of the Dru, but massive overhangs made it nearly impossible for teams to rappel to the stranded men.

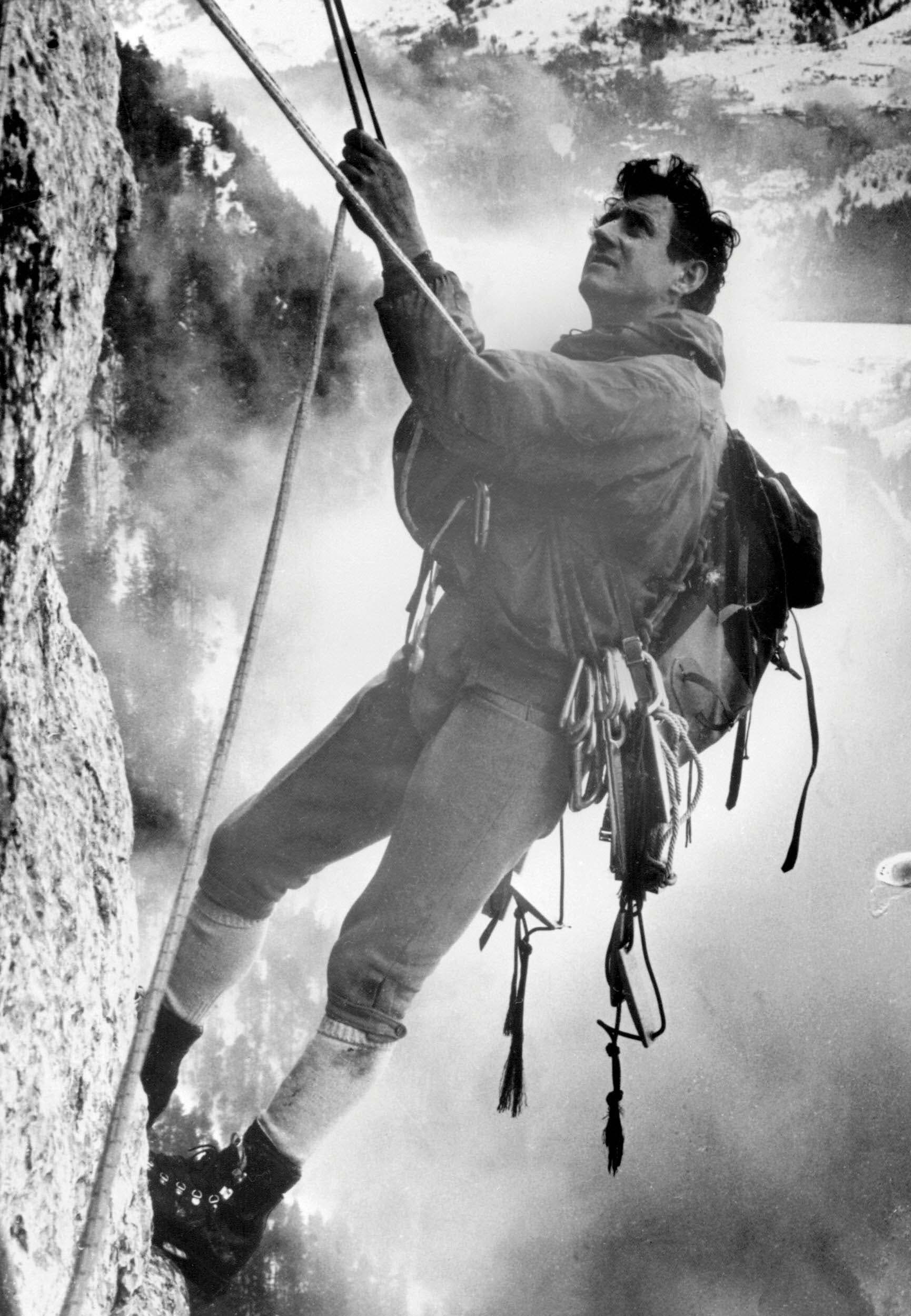

The sole American on the glacier, and part of a second rescue team, was a tall, angular man with patched climbing knickers and a scarf nearly as long as he was. His face, one journalist later wrote, “had something of the beauty of the paintings of the Christian saints.” His eyes, an impish, childlike blue, twinkled when he smiled. In a few days he would be one of the most famous people in Europe. In three years he would be found dead in a campground in Jackson, Wyoming. His name was Gary Hemming, and he carried with him a conviction that in turn carried the five other soaked climbers upwards in the gray predawn drizzle. They would save the men who were trapped, thousands of feet above, by climbing up through the storm.

***

In a range rich in iconic summits, the Drus—the Grand and Petit—stand out. While both are spectacular summits, it was the Petit Dru, at 3,730 meters (24 meters shorter than its taller counterpart), that caught the eye of Chamonix alpinists. Its North and West faces are both steep, imposing walls of granite nearly as tall as El Capitan in Yosemite. It wasn’t until after World War I that alpinists even considered the faces possible.

***

In 1935, the first ascent of the North Face fell to Pierre Allain and Raymond Leininger. Allain was, in the words of the climbing chronologist, Ian Parnell, “decades ahead of his time.” He invented equipment still used today: lightweight half-height sleeping bags, inflatable mattresses and the first modern rock shoe. Allain honed his skills on the boulders of Fontainebleau outside of Paris, unlike many cloistered traditionalists of his era. His equipment, training and approach were, for 1935, breathtakingly modern. On the North Face, Allain and Leininger brought one ice axe between them to save weight. They used a single 7mm rope, five pitons, six carabiners and a prototype pair of Allain’s rock shoes. The pair freed the entire climb at 5.9. In 1935, and perhaps still, it was an absolute tour de force.

The first ascent of the neighboring West Face, in 1952, was such an undertaking that Guido Magnone, one of the first ascensionists, wrote an entire book about the endeavor. The signature beauty of the climb lay in the perfect, 90-meter diedre, a dihedral of granite high up the face. On the first attempt, Magnone, Lucien Bréardini and Adrien Dagory, exhausted from the oppressive heat and short on equipment, dead-ended above the dièdre, where blank slabs gave way to a 30-meter overhang. On their second try, the team, this time with Marcel Lainé, traversed in above the dihedral by placing a line of primitive bolts (gulots), from the neighboring North Face, skipping the section of the West Face they’d previously climbed. This time the team committed to an irreversible pendulum traverse across the slabs and launched up the overhang. The route constituted the cutting edge of rock climbing for 1952. In the wet, icy conditions of 1966, however, the same features conspired to form something more sinister: the perfect trap.

***

“There is,” wrote the journalist Jeremy Bernstein, in a 1971 article for The New Yorker about rescues in the French Alps, “in the back of the young climber’s mind an awareness of the efficient rescue service in the valley—the realization that, if the worst comes to the worst, ‘on vous cherche.’”

Heinz Ramisch and Hermann Schriddel had set off up the Petit Dru on August 14, five days before Hemming’s team labored towards them on the Mer de Glace. Ramisch, a 22-year-old student from Karlsruhe, Germany, had never once climbed with the 30-year-old Schriddel, who worked as an auto mechanic. They had only just met, encamped with a cluster of their countrymen in the Montenvers campground.

Accidents typically leave a distinct trail of seemingly inconsequential mistakes. But then, alpinism is rife with instances— both of ascent and disaster—where small things go wrong, apparently unnoticed by the unlucky protagonists. A razor-thin line has always separated the brilliant from the bumbling.

Ramisch and Schriddel made average, but decent, progress up the easy lower two-thirds of the wall. Planning on two or three days on the face, the two pared down their bivouac equipment to the minimum standard at the time: waterproof anoraks and down jackets, as well as a rudimentary two-man bivy sack.

On the second day, Schriddel took a 30-foot leader fall, badly bruising his ribs. Ramisch’s throat, sore from dehydration, hurt so much he couldn’t swallow. Nonetheless, on the 16th, even after bivouacking through a violent thunderstorm, they started up the dihedral, ignoring the growing clouds and the ice now plastering the face. The decision to continue, instead of retreat, would activate the most complicated rescue in the history of mountain climbing. They made impossibly slow progress. Schriddel fell yet again, and Ramisch, who caught him on a hip belay, badly cut his hands. That afternoon, having taken all day to climb the signature 90-meter dihedral, the Germans committed to the pendulum. Here, they confronted two options: Magnone’s bolt ladder, leading to safety and the less difficult North Face, or continuing up the horribly iced-up overhangs to the summit. Before the team had left Montenvers, they had agreed to wave a red parka in case of trouble to their anxious countrymen below.

After another bivouac, this time on the impossibly exposed ledge beneath the roofs, unable to commit to either the icy overhangs or the old bolt ladder, and certainly unable to reverse the pendulum and rappel, the exhausted Germans made themselves as comfortable as they could, took off the red jacket, and furiously signaled for help.

***

Lother Mauch was frustrated. It was Thursday, August 18. The rain drummed down on the café roof in Courmayeur, on the Italian side of the Alps. He had just retreated from the mountains, and now the weather was getting worse. Mauch, a 29-year-old German with handsome, dark features—he occasionally funded alpine-climbing trips with modeling gigs for fashion magazines—had been planning on an ascent of one of Chamonix’s longest routes, the Peuterey Integral. Across from him, reading that day’s Dauphine Libéré, a French paper, sat Gary Hemming, Mauch’s partner and mentor. The pair had made numerous ascents together: “Gary taught me everything during two summer seasons, when I climbed mostly with him,” Mauch remembers.

***

With Hemming, nothing was as it seemed. Hemming was born in 1934 in Pasadena, California, but when he became famous, he loved toying with reporters and friends alike, mischievously lying about his age, his height, his history. In his obituary, Royal Robbins would describe him as “a climber widely believed to have been among the best in the world.” Yet he climbed well only sporadically, often moodily lapsing into a listlessness that caused his abilities to suffer as much as his partners. Tom Frost, who climbed a new route with Hemming, John Harlin and Stewart Fulton on the Aguille de Fou in 1963, tells me that “his limitations were personal, not physical. He just wasn’t that stable a personality.”

For Hemming, as for others of his generation, alpinism was more a crucible than a sport. He told an admiring reporter from Elle after the rescue: “The mountain is an initiation which is renewed every year. You go there, you test yourself, you find yourself again. Afterwards, you are more able to accept yourself.”

Though Hemming had climbed with Robbins and Frost—men who practically invented modern climbing—he lingered only on the fringes of Yosemite in the late 1950s. His ramblings, from the late 1950s to the early 1960s, took him from Wyoming to Mexico, to British Columbia, to New York City: an early prototype of the dirtbag. Beginning in the summer of 1959, Hemming gravitated towards the Tetons, where he worked as a guide for Exum Mountaineering.

Mercurial even at his best, Hemming was legendary in his moodiness. He exploded into fits of rage, often against inanimate objects. Partners recall how his moods and tempers would affect his climbing. “He was very temperamental,” remembers Konrad Kirch, a friend of Hemming’s and a climbing partner of John Harlin’s. “And he was very fluctuating in his abilities.” Hemming, stalk thin and around 6-foot-4, would often provoke fights he knew he’d lose. Once, he was badly beaten outside a bar in the Tetons by three cowboys he’d been glowering at through his noticeably long, tangled hair. “Death,” he wrote in his diary, “is chasing me in this country. I have to leave before it catches me.”

In 1960, Harlin, an American Air Force pilot stationed in Germany, wrote to Hemming, whom he’d climbed with back in California in 1954. Hemming, attracted by the allure of the European Alps and sickened by the perceived restraints of American society, soon joined him.

While both men had made little ripples on the fringes of climbing development in California, they made quite the splash in Europe, bringing Yosemite tactics to the large, glaciated mountains of the Western Alps. Apart from a new route on the Fou, Hemming completed the first American ascent of the Walker Spur of the Grandes Jorasses, and the American Direct on the Petit Dru, with Robbins in the summer of 1962. (The Direct, as luck would have it, joined the original West Face route at the 90-meter dihedral where the two Germans now found themselves trapped.) Though Hemming climbed with others, it was with Harlin that he felt most strongly the electrifying power of partnership. And while they would argue, notoriously berating each other as they dangled from some precarious belay, they quickly became the most famous Americans in the Alps.

Guided by Hemming’s fatalistic, medieval sense of chivalry, the two were part and parcel to some of the Alps’ most famous rescues. Rescue duties at the time were divided among three groups seasonally— the École Nationale de Ski et d’Alpinisme, or E.N.S.A. (the guide-training school of France), the guides themselves, and lastly the École de Haute Montagne (the training school of the French Alpine troops). Help from talented “recreational” alpinists such as Hemming and Harlin was a necessary addition, but not always welcome. “Gary never liked the Chamonix guides,” says Lothar Mauch. The rift had begun when Hemming and Harlin offered their assistance during the famous disaster on the Central Pillar of Freney in 1961. The ordeal killed four out of seven climbers, and left the two Americans disenchanted over the lassitude of the French rescuers. This rift deepened when Hemming was booted out of an E.N.S.A. course in 1962 for refusing to shave his unruly beard. Later, he shaved it off all the same.

Hemming’s stubborn romanticism plagued him even more in the lowlands. His love life was plentiful, but abysmal. By 1966, he’d amassed a tangle of relationships that were complicated even considering the decade. He had a son with a Frenchwoman in 1963, and the couple maintained an open relationship. But he had also fallen in love with a young French student to whom he prescribed unrealistic expectations and mythic proportions.

When the two met, the woman was 17 years old. Hemming pestered her with hundreds of letters. He climbed over the hedges of her parents’ house in Paris. Her sister, unamused, promptly phoned the police, and Hemming was arrested. Hemming’s beatnik predilections baffled most of his American contemporaries. Frost muses, “He was portrayed as a romantic in the media. But, he wasn’t willing to step up to the plate to be a father or a husband.” For the French, who have always gathered rebellious spirits to their collective bosoms—from Joan of Arc to Arthur Rimbaud—the man brooding in the café with Lothar Mauch on that rainy day in August could not have been better poised for stardom.

John Harlin’s obsession was a route up the North Face of the Eiger in winter. By winter of 1966 he had made multiple attempts over five years, and finally recruited a team of alpinists whose names read like a who’s who of alpinism in the 1960s: Englishmen Chris Bonington and Don Whillans, the Scottish climber Dougal Haston, and the brilliant American Layton Kor. But the attempt had ended in disaster on March 22, as Harlin ascended a 7mm rope halfway up the face. The tiny perlon cord wore over a sharp edge, and Harlin fell. The journalist Peter Gillman, on assignment for the Daily Telegraph, watched in horror from Kleine Scheiddeg through his telescope. “Suddenly I saw a figure in red cartwheeling downwards. It fell too fast for me to follow it.”

[Also Read John Long: The Jump | Ascent]

Five months later, as Hemming read the Dauphine Libéré in Courmayeur at noon on August 18, he was doubtless still reeling from Harlin’s death. “John is one of my dearest friends,” he wrote in his diary. “His death I refuse to accept and so far as I am concerned he is still very much alive … I cannot climb alone next summer.”

The article that interested him involved the two Germans, trapped high up on the Dru, on terrain he was intimately familiar with. The École de Haute Montagne had dispatched some 40 troops to the summit of the Dru, orchestrated from Chamonix by Colonel André Gonnet. The plan was to lower a steel winch down and haul the stranded climbers back up. An Allouette helicopter had buzzed past the Germans, and through the clouds confirmed they were alive, but with the atrocious weather, could do little else.

With the rescuers came the press. “Every newspaper in Western Europe carried details of the rescue on its front pages,” wrote Bernstein in The New Yorker. A helicopter from the O.R.T.F., the official French radio and television network, joined the fray. The Petit Dru had been besieged.

Mauch took a little convincing before he would go with Hemming. “Gary said, ‘If they do it like that, trying to go down from the top of the Dru, they might never get them out.’ He knew very well about the overhangs on the West Face,” he says.

But the tunnel from Courmayeur to Chamonix was expensive, and the two climbers had just paid the hefty fee. Hemming pressed—what better crusade than a daring rescue? He would recount in an ensuing Paris Match article: “This rescue is a great ascent—a real adventure. But what’s important is that it involves the lives of two persons, two companions. If we make it, it will mean a lot more than just another windy summit, don’t you agree?”

Eventually Mauch agreed to return to Chamonix, and to accompany Hemming up the Dru. “It was bad weather,” he reasons, with the logic of any obsessed alpinist. “There was nothing else to [do].” Hemming’s plan, to reach the Germans by climbing up to them and rappelling, seemed simple enough. But rescues in Chamonix were overly complicated affairs, and to rappel a face that huge was still daunting, given the techniques and equipment of 1966. “The rescue organization,” says Mauch, “was very, very bad at the time.”

At 3 o’clock on the afternoon of the 18th, Mauch and Hemming introduced themselves to Colonel Gonnet, who, to his great consternation, realized he was suddenly parlaying with the same upstart American who had been kicked out of E.N.S.A. for refusing to shave.

A man wholly different from Gary Hemming was also paying particular attention to the unfolding saga on the Petit Dru. René Desmaison was one of the best alpinists in France. The 36-year-old had made the fourth ascent of the West Face of the Dru. Unsatisfied, he completed the first winter ascent of the line, and then returned to solo it. In 1958, he and Jean Couzy climbed a new route on the north face of the Grandes Jorasses. He was a member of Lionel Terray’s expedition to Jannu in 1962. Perhaps only Walter Bonatti exceeded Desmaison in ushering in the new era of modern European alpinism.

Unlike Hemming, who flitted between bohemian dalliances and climbing with a calculated nonchalance, Desmaison was an obsessive career alpinist, and one of the foremost guides in Chamonix. And like many professional climbers desperate to fund their endeavors, Desmaison possessed a canny ability to manipulate his adventures and present them—for a cost—to the mainstream media. “He had a reputation in Chamonix,” remembers Mauch, “for working with Paris Match and the radio station.”

In Desmaison’s defense, alpinists with middling bank accounts have always relied on publicity stunts to fund their endeavors. Harlin’s death on the Eiger had received massive coverage; the French magazine Paris Match had taken to keeping a full-time correspondent on hand in Chamonix during the busy summer alpine season in order to snatch up rescue stories as quickly as hapless climbers could ascend into trouble.

Like Hemming, Desmaison realized that climbing up to the Germans was the surest method of rescue. He decided, without informing the world’s oldest organized mountain-guiding association and his employer, Chamonix’s venerated Companie des Guides (who hadn’t yet ventured forth a rescue effort), to strike off up the West Face to save the Germans.

“Amateur or professional,” he wrote in Total Alpinism, “any climber has the right, indeed the duty, to save life.” What he neglected to reveal, in his chapter on the Dru (entitled “The Maverick”), was the exclusive contract he signed with Paris Match before setting off.

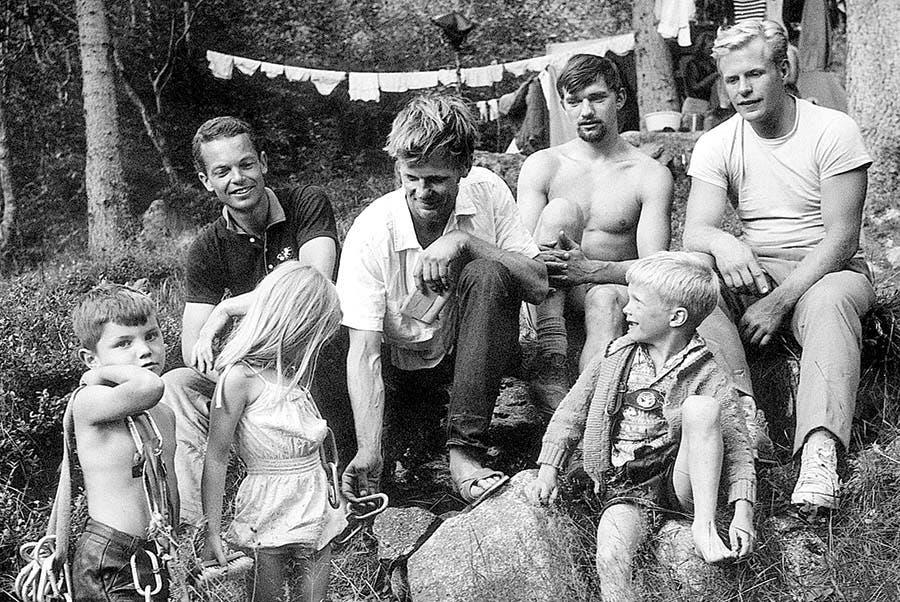

François Guillot, another young alpinist, was drinking a beer and watching the rain in the Hotel de Paris when he saw Mauch and Hemming. Hurriedly, they explained their plan. Within hours of the meeting with Gonnet, Hemming had assembled an improvised team of rescuers: Gerhard Baur was a young German in his early 20s who knew Ramisch and Schriddel. Gilles Bodin was a French guide. Mick Burke, who Konrad Kirch remembers as a “small, dirty- looking climber,” was a talented Brit who would later go missing on the South Face of Everest. He was also crucially well versed in knowledge of the West Face, having rappelled the American Direct, Robbins and Hemming’s line, when his partner had broken an arm due to rockfall.

But Guillot was the lynchpin. At 22, he was one of the youngest rescuers, but also one of the strongest. “I was a pure amateur at the time,” he laughs. “I was coming off a six-week trip to the Caucus mountains. So I was in good shape. Gary knew me, and knew I was a decent climber, and asked me to come.”

By 7:00 that evening, Hemming and his team were on a specially scheduled cog- railway train headed up to the glacier. Early the next morning, the men climbed up the Dru Couloir, an inhospitable place in the best of conditions. Now, as sleet spat down, the couloir was a death trap, and the men, laden with heavy rucksacks and soaked already to the bone, resorted to every trick in the book to make upward progress. In the snow and sleet, the slabs and ledges proved impossible. Guillot led a few pitches and then retreated back down, and the men huddled into their down sleeping bags and two-man bivy sacks, little better off than the Germans, who remained crouched on their teeny ledge, rationing nuts and shivering through their fourth night in the same forlorn spot.

Meanwhile, Desmaison and an aspirant guide and photographer named Vincent Mercié, had taken a helicopter to the base of the couloir and were soon also dodging the fusillade of stones and debris. The two Frenchmen hunkered down for the night on a sheltered ledge, unable to cross over to Hemming and his team until morning, when the cold had frozen the couloir enough to allow safe passage. In the morning, Baur tossed Desmaison a rope. The two parties converged. Now they were eight. What went through Hemming’s mind as Desmaison and Mercié popped up on the ledge next to him? Desmaison, according to his own account, chastised the team for moving too slowly, and conjured a plan of action. “Gary knew very well that Desmaison was there for money,” says Mauch.

For Hemming, the helpless, troubled romantic, the Dru rescue glimmered as the spiritual crusade he had always dreamed of. For Desmaison, whose career suddenly hung in the balance, saving the Germans, and the race to beat his colleagues, meant everything. The idealist and the opportunist would now have to work their way together up the mountain as 10 million Europeans listened, read and watched the drama unfurl across the granite of the Dru.

“Desmaison wanted to do the rescue to take pictures, to sell the pictures to Paris Match, and you could speak for hours about that,” Guillot says. “However, he was perfectly in line with his approach, and he was a professional alpinist.”

They came up with a plan of action. Guillot and Hemming would go first, Desmaison and Mercié second, and Mauch, Baur, Bodin and Burke would tackle the less glamorous but equally daunting task of hauling the heavy rescue and bivouac equipment up the verglassed face.

That Hemming and Desmaison, not exactly slouches when it came to alpinism, allowed the young Guillot to lead the entire West Face speaks more to the 22-year-old’s abilities than anything else. Bodin recalled in an interview in 2002, “Without Guillot, we may still have succeeded. But, it would have taken twice as much time.”

Hemming belayed as the young Frenchman furiously hammered his way up the West Face. Word had gotten out about the tall, valiant Californian racing his improvised team up through the clouds. Even if he was only feeding out rope, the press was in love. Less enamored was the Companie des Guides with Desmaison. For the stoic clique, Desmaison’s latest publicity stunt constituted the final straw.

There were now three rescue groups on the Dru. The École de Haute Montagne’s 40 volunteers, soldiers and guides on the summit were still attempting to lower a steel cable down to the Germans. E.N.S.A. had finally sent its four alpinists to climb Pierre Allain’s route on the North Face, and Hemming and Desmaison’s team was about to reach the Germans by way of the original West Face route.

The three rescue entities were drawing closer to the Germans, and, as notably to the swarms of reporters below, to each other.

On Saturday the 20th, as Guillot led the climbers up the West Face, rescue efforts were compounding elsewhere, too. Four E.N.S.A. climbers—all colleagues of Desmaison’s—had begun climbing up the less-technical North Face, with the intent of traversing in on Magnone’s aged gulots.

The eight men on the West Face bivouacked below the dièdre. Now they were a mere 300 feet below the two Germans. In one day, through ferocious storms, Guillot had led what had taken Ramisch and Schriddel two days the week before. Around the corner, the E.N.S.A. party bivouacked at around the same height. Hemming shouted to the Germans through the mist, but could hear nothing.

Everyone settled down in the dark. Their sleeping bags and clothes were soaked completely through. The next morning, the Germans responded to Hemming’s shouts, and the rescuers attacked the dihedral. Simultaneously, the E.N.S.A. team began traversing in from the North Face. Higher up, Gonnet’s men were still trying to lower a steel cable from the summit of the Dru. They had enlisted the help of some volunteers, including a young man named Wolfgang Egle, a friend of the Germans, who was rappelling above the four E.N.S.A. climbers when he somehow became tangled in the ropes on the icy north face and was strangled to death.

Desmaison remembers the incident in Total Alpinism: “Luckily, this tragic occurrence was invisible from the West Face and, naturally, we did not mention it to the two Germans.”

Guillot and Hemming reached the stranded German climbers a little after noon on Sunday, August 21—a full week after Ramisch and Schriddel had started up the face. Apart from the minor injuries sustained while climbing, and the obvious hunger, cold and exhaustion, they were fine.

As Hemming reached Ramisch and Schridde, Yves Pollet-Villard, one of the guides on the E.N.S.A. team, was making the traverse across Magnone’s gulots. Pollet- Villard was a colleague of Desmaison’s. Moreover, the two had climbed on Jannu together, and routinely roped up around Chamonix. Understandably furious at Desmaison’s decision to rescue the Germans himself, without prior consultation, he now asked the renegade West Face team what their intentions were.

Guillot remembers thinking that, hubris aside, Hemming and Desmaison’s plan was the safer of the two. The ropework involved with ferrying the two exhausted Germans up and across to the North Face was doable, but complicated, and dangerous considering the Germans’ deteriorating condition. Burke and Hemming’s knowledge of the American Direct, which shot down from the ledge in a perfect line, was the safest option.

“At that time,” says Guillot, “rappelling down a 900-meter-high face was something enormous. And certainly for Desmaison, and also for Gary, it was a question of pride. They wanted to keep the two Germans with them, and not give them to the other team. And this created a lot of problems for my friend Desmaison after that.”

One of the North Face rescuers fuming at Desmaison and Hemming’s insolence was Gérard Devouassoux. Five years later, in February 1971, Devouassoux would be charged with rescuing Desmaison and his young partner Serge Gousseault from the top of the Grandes Jorasses after the exhausted climbers had become stuck at the top of a new route. By the time the rescue arrived, Gousseault was dead, and Desmaison was barely alive. Desmaison would accuse the rescuers of intentionally dragging their feet to punish him for his role on the Dru rescue while Devouassoux and the other rescuers would claim that Desmaison’s need for the spotlight—he hauled heavy radio equipment up the wall so he could broadcast daily updates—had caused him to climb too slowly.

Today, many Chamoniards still whisper about Devouassoux’s “revenge,” though few are willing to comment on it publicly. On the ledge in 1966, Guillot, uninvolved in the older men’s weighty quarrels, chimed in, asking for the guides to lower a stuff sack full of snacks.

Desmaison continues: “The cloud ceiling was now about 11,800 feet. The air seemed humid. In spite of the altitude it did not seem cold. It was obviously only a matter of time before the storm broke.”

A helicopter whirred past to snap photographs, and the team rigged the Germans with modern nylon harnesses and retreated to their last bivouac below the dihedral. That night, as the men prepared for the worst, another storm of insatiable violence lashed the West Face. The rescuers debated untying from the pitons, humming with electricity.

On the 22nd, Mick Burke led the team, and the rescued Germans, down the mountain, soaked, exhausted and elated. In the dark, they stepped onto the glacier. In the morning, when, observed Bernstein in The New Yorker, “The light was bright enough so that the O.R.T.F. television cameras could obtain excellent pictures,” the team was helicoptered back to Chamonix. In the black-and-white footage, Hemming appears a little tired. His pants are tattered and worn, and a red knit cap is perched at a perfect angle over his head. He laughs easily with the reporters despite his fatigue, throwing his head back at his own sardonic remarks. His French is good, with a slight American twang. When a reporter asks if he ever thought about giving up, he fixes his gaze: “Jamais. Jamais.” “He loved it,” Konrad Kirch remembers.

While they had toiled on the Dru, Desmaison had slyly hidden his contract with Paris Match from the other rescuers, but, back in Chamonix, he told an understandably livid Hemming. “Gary was not the type of guy who would make a big fuss about fighting with Réne,” says Guillot. “But, I’m sure it was a pretty tough discussion between the two of them.”

While the rescue elevated Hemming to mythic proportions, Desmaison’s actions caused the Companie des Guides to fire him instantly. He would spend the rest of his life feuding and feeling as if Hemming had gotten an unfair portion of the credit for the rescue. “Well done, Gary!” he wrote. “Gary Hemming was the hero of the hour, the man who had saved the two Germans, the man everybody wanted to touch, and interview, and see. You would have thought he had done the entire rescue single-handed; nobody showed the slightest interest in the rest of us.”

Guillot, who later became a guide, spent years quietly reading Desmaison’s increasingly exaggerated accounts of the affair. “René hid everything about the job we did,” he says. “In all his books he mentions the rescue, and each time his role grows, as if he’d done everything himself. I spent my life looking at what René was writing in his books and saying, ‘Bastard; he could have spoken a little bit more about my role!’”

While Hemming basked in the limelight and Desmaison tussled with the Companie des Guides, Lothar Mauch engaged in a heroism of a different sort. Two men had been saved; another young man was dead. The parents of Wolfgang Egle, the man who still hung from the North Face of the Dru, had come to Chamonix. Mauch remembers feeling uneasy. Devouassoux, the E.N.S.A. climber who had reached Egle moments after his death, had delegated the task of meeting the parents to Mauch. “He saw the guy dying before his eyes! I didn’t see anything,” says Mauch. “I was on the other side of the mountain. The parents asked me questions I couldn’t answer. It wasn’t right.”

After the hubbub subsided, a different sort of recovery took place, as rescuers somberly cut down Egle’s body and returned it to Chamonix.

In James Salter’s novel Solo Faces, which is loosely based on the life of Hemming, the title character successfully fades back into an anonymous, vagabond existence after his dangerous brush with fame. The real ending was less tidy. Hemming’s face had been seen on every television station in Europe. He wrote his own account of the rescue for Paris Match. He was put up in the Paris flats of intellectuals and journalists. He played a character on a French television mini-series. Women stopped him on the street. He was “le Beatnik,” with, as Salter puts it, “a saintly smile and the vascular system of a marathon runner.”

“Gary was uneasy and unhappy in the United States,” Robbins would write in his obituary. In 1969, as his celebrité ebbed, Hemming returned to the Tetons. He had taken, for some morbid reason, to keeping a revolver in his rucksack. Hemming’s idealism, which had so embodied the 1960s to his European fans, would be lost, seemingly in time with the tumultuous decade itself, which began with such innocence and ended in unfathomable violence. “Anyone,” he reportedly quipped, “can be a hero one day and a motherfucker the next.” On the night of August 6, 1969, he attended a party with his old friend Bill Briggs at the Jenny Lake Campground.

Hemming, who loved getting into fights he’d lose, needled one of the partygoers about the inferiority of American guides to their Gallic counterparts. The two scuffled, with the much-stronger Exum guide pacifying the wildly drunk Hemming. Later, Hemming quarreled with his girlfriend at the time, snatched his rucksack out from her car, and disappeared angrily into the night, firing a shot from his revolver into the air. Briggs, attempting to cling to much- needed sleep before he met his clients in the morning, heard a second shot at some point during the night. “I recall thinking probably Gary had committed suicide, or perhaps shot the girl.” In the morning he found Hemming’s long body, splayed out in the grass.

***

Desmaison’s Accident on the Grandes Jorasses and the death of Serge Gousseault put him even further at odds with the Chamonix establishment. He constantly warred with the guides he swore abandoned him. Whatever his earthly motives, his routes are considered among the greatest in the Alps. A modern alpinist, Jon Griffith, wrote on his web page after repeating Desmaison’s pièce de résistance on the Jorasses: “Among all the hundreds of classics … there will always remain … the ones that combine five star climbing with an epic tale enshrined in our sport. The Desmaison-Gousseault is one of them.” In 2007, Desmaison died at the age of 77.

Mauch, Guillot, Baur and Bodin are still alive. When I spoke with Mauch, he was in Spain, enjoying the sunset after a day of clipping bolts. He and Guillot are still friends, having met in the bar that rainy night in the Hotel de Paris, over 50 years ago. I chatted with Guillot, who was spending time in Marseilles. His shoulders, he complains, are giving him trouble. In his mid-70s, he still climbs 5.11 (5.12, according to Mauch). “Gary had the fame,” he told me. “And that’s O.K.”

Most of the rescuers turned toward inevitable careers in the mountains. Gerhard Baur became a successful mountain filmmaker. Guillot and Bodin spent lifetimes guiding in the Mont Blanc Massif, though the fame and prestige awarded the rescuers eventually faded. “Ask the youngsters, and you will see there are not so many who know!” Bodin joked in a 2002 interview.

It is difficult to directly connect Desmaison and Gousseault’s tragedy on the Grandes Jorasses with the rescue, but in a town where politics and climbing are tied so tightly together, not impossible. Hemming, turned celebrity overnight, unraveled over his three remaining years. His diaries constantly question his fame. “Now I know with certainty the impossible situation of being ‘somebody important,’” he wrote. While the other rescuers simply became dramatis personae, and a mountain rescue became a confounding muddle of egos, the survivors are probably relieved to have remained relatively anonymous: the two men who gained the most from those stormy days on the Dru suffered in accordance with their fame.

Michael Wejchert is a writer and guides for the International Mountain Climbing School in North Conway, New Hampshire.

This feature article was first published in the 50th anniversary edition of Ascent in 2017.