A Climber We Lost: David Turner

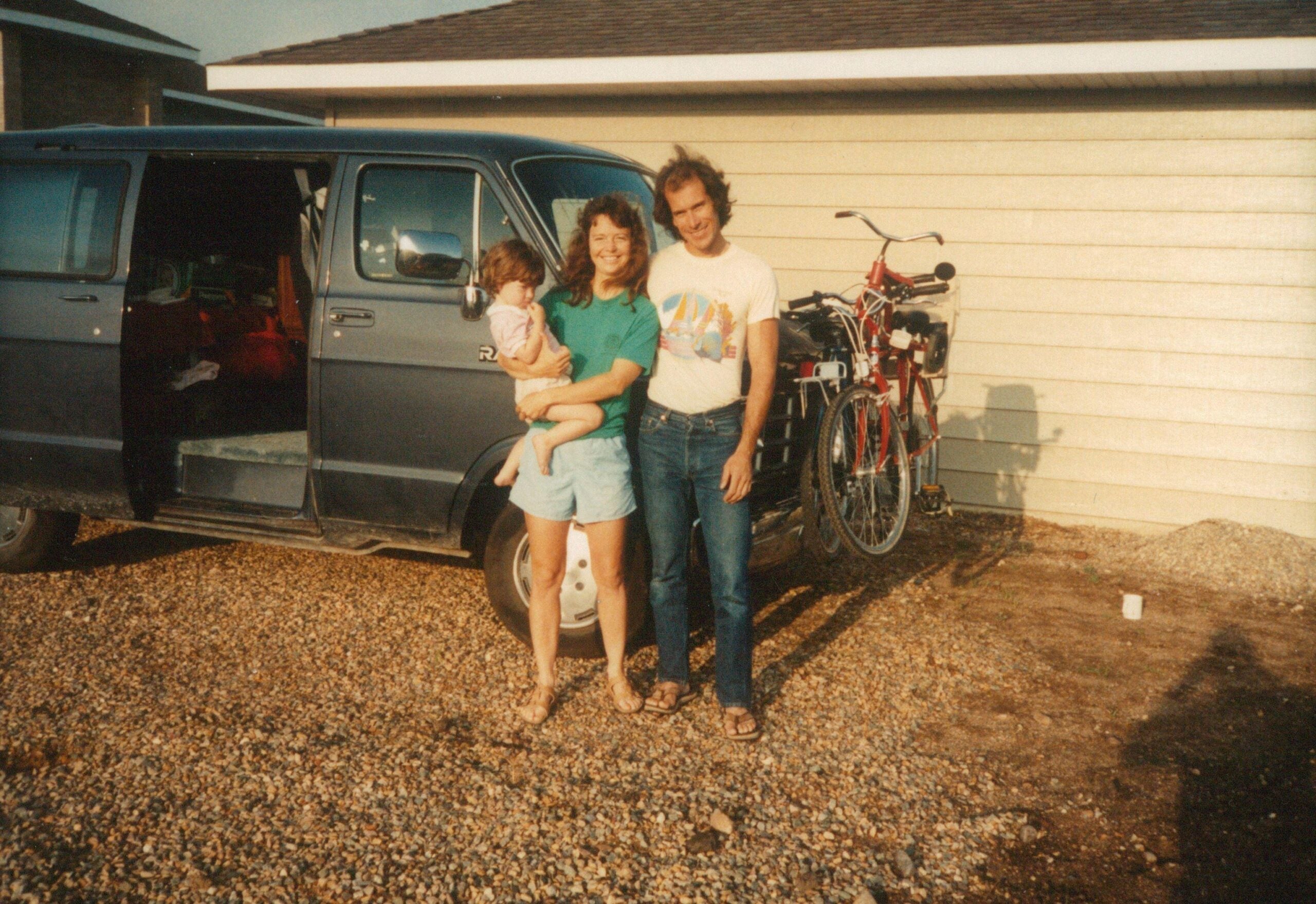

Stephanie, Nancy, and Dave Turner on their 15-month road trip in 1989/1990. Dave quit his job and the family loaded up in the van, traveling around the American and Canadian West to hike and climb, well before #vanlife was even a thing. (Photo: Nancy Turner)

You can read the full tribute to Climbers We Lost in 2023 here.

Dave Turner, 70, January 5

The Colorado—and American—climbing community lost one of its unsung heroes when David Ahle Turner, who went by Dave, passed away on January 5, 2023, after a skiing accident at Aspen Highlands, Colorado. Two days earlier on the final run of the day, Turner, an expert and lifelong skier, hit a catwalk at the bottom of a black-diamond run while carrying speed and launched into a grove of aspen trees, sustaining catastrophic injuries.

Turner was a fixture in the Colorado climbing scene. He was born in Denver in July 1952 and got into climbing in 1976 while attending Colorado College in Colorado Springs, when some dormmates invited him out to the rock. This was back in the era of pitons and Whillans harnesses, and Turner’s first rock boots were the infamously stiff “blue suede shoes” sold by Royal Robbins. His first lead was the 45-foot 5.6 South Ridge of White Twin spire in the Garden of the Gods, an experience he described in an outline for a book as being “very exposed and ‘real’ and intimidating and exhilarating.”

As his skills evolved, Turner racked up an impressive all-around ticklist, though you’d never have known it, given how modest he was about his accomplishments. These included a climb of the fearsome Mount Temple, Canada, in 1988 with Gregg Oliveri; an ascent of the Nose of El Capitan with Andy Selters in 1989; an onsight free solo of the notoriously nebulous Northcutt-Carter (III 5.7 at the time) on Hallet Peak, Colorado, in 1990, during which he got off-route and had to keep his wits about him; the first free ascent of the Andromeda Strain (5.11a WI 4+ M6) on Canada’s Mount Andromeda in 1997 with John Culberson; and a summit of Aguja Poincenot in Patagonia, also with Culberson, in 2001. A lifelong outdoor athlete, Turner was perpetually fit, and you’d see him bouldering hard and climbing 5.12s at the gym and at crags around Boulder, Colorado, well into his sixties.

Throughout his life, Turner had many metiérs, primarily in the outdoor-education, guiding, and law arenas. He taught rock climbing in North Carolina, worked for Minnesota Outward Bound, guided for the American Alpine Institute, and taught skiing at Loveland Ski Basin in Colorado. As a lawyer, Turner practiced estate planning and probate litigation; after winding down his practice in Boulder, Colorado, in 2019 and 2020, he retired with his wife, Nancy, to live in Basalt, Colorado, where they bought a house in October 2021. Married for 40 years, the pair were some of the first van lifers. They hit the road in 1989 for fifteen months to hike and climb when their daughter Stephanie was just a toddler, stopping at destination areas like the Tetons, Joshua Tree, the Canadian Rockies, Mount Lemmon, Utah, and Bishop. (The Turners also have a second, younger daughter, May.)

On the climbing-access front, Turner’s contributions are immeasurable. Using his legal expertise—he earned a law degree from the University of Colorado in 1978—he helped set a precedent for positive climber-land manager interface that has become a model throughout Colorado, and perhaps America. In 1989, the City of Boulder established a bolting moratorium in Boulder Mountain Parks, which included the Flatirons, a venerable sandstone scrambling, multi-pitch, and traditional area above town. This curtailed the burgeoning sport-climbing development, but also made it effectively impossible to upgrade aging bolts. As a result, climbers largely stopped frequenting the Flatirons for sport climbing, and rappel anchors on the summits began to fall into dangerous disrepair.

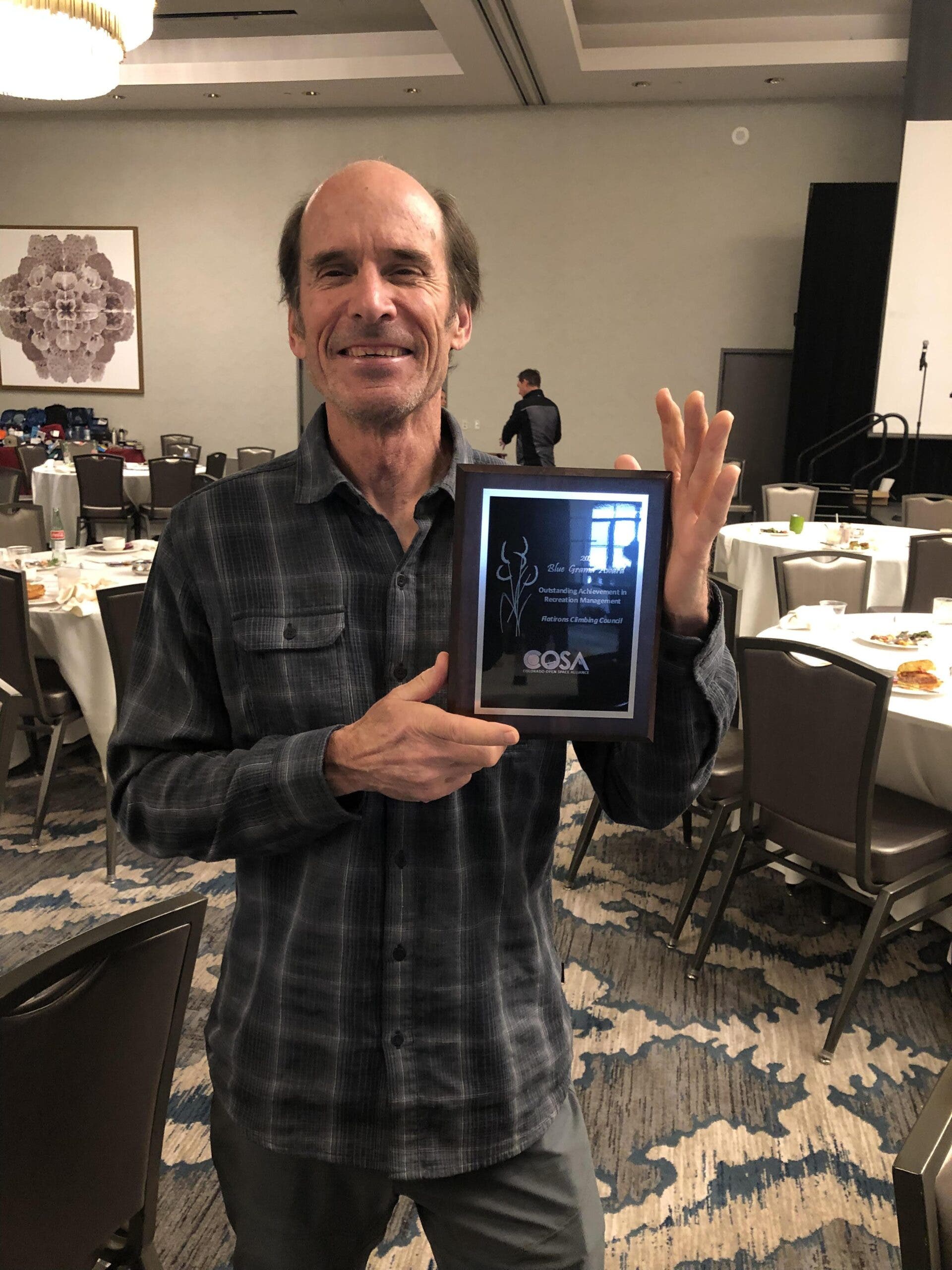

In the late 1990s, Turner, along with Terry Murphy and Rick Thompson, then the national access and acquisitions director at the Access Fund, came together with others to form the Flatirons Climbing Council (FCC; founded in 1998), an organization of climbers that would interface directly with Open Space and Mountain Parks (OSMP) to try to resolve these issues. (Turner also served on the Access Fund’s legal committee for years and was president of the FCC from 2001 through 2007.) Through countless meetings, über-patient diplomacy, and steady lobbying, the FCC succeeded in opening the Flatirons to bolting on a permit system, starting in 2003 with a pilot area on Dinosaur Mountain that has since expanded to include numerous formations, including mega-destination crags like Seal Rock and the Slab. The program, in which a board of climbers on the Fixed Hardware Review Committee vets applications before forwarding them along to OSMP, has been a wild success, with each of the three annual cycles seeing more than its quota of three applications. The Flatirons are a vibrant climbing area again thanks to Turner’s vision and effort, with dozens of new routes up to 5.14c, plus all the 1980s classics updated with modern, stainless-steel hardware.

Wrote Thompson in an email, “[The FCC’s] positive impact on the climbing scene in the legendary Flatirons has set a standard of excellence, and today they continue their excellent work, sponsoring annual climber volunteer days, educating on climber conservation issues, and conveying the goodwill of the climbing community. It is largely because of Dave’s involvement that the organization has been so successful.”

One of the last times I saw Dave was in 2021, on a trail day he’d put together to engineer an approach through talus, deadfall, and poison ivy up to Overhang Rock in Bear Canyon. It was hot and smoky that July day, and the weed-pulling and rock work were grueling in the heat. But there was Dave with his Cheshire cat grin, making friendly banter with the other volunteers, looking honed and strong and so much younger than his 67 years as he uncomplainingly moved giant rocks around to build steps.

One of my finest memories of Dave was helping him and the brothers Roger and Bill Briggs bolt the Direct West Face of the Third Flatiron, a technical, rope-stretching 5.11 up the iconic formation’s western skyline buttress, in August 2009. Climbers had been playing on the route for years on toprope, but without bolts it was clearly a death lead, and so remained only a dream until the Third Flatiron reopened to bolting in the Aughties. Drill (and bolting permit) in hand, we hiked in, did a final toprope run to confirm the clips, and drilled the line, which has nine clips in addition to the odd cam.

Wrote Dave, with typical modesty, in his Mountain Project description, “No first ascension credits are given because many have contributed to the creation of this magnificent route. Some have toproped portions of it as early as the ’70s, others have worked long hours to re-open the Flatirons to new fixed anchors, after a twenty-year ban, which enabled wonderful routes such as this to be created. Others have supported the efforts of the Access Fund and the Flatirons Climbing Council, volunteered for trail projects, and otherwise contributed to the greater climbing community of Boulder. This is indeed a communal route on Boulder’s iconic crag.” Still, it was Dave who made the first lead, cruising through thin crimps, heads-up slab moves, and a final, pumpy roof with such poise and natural ease that when it came my turn to lead, fighting fear, Elvis leg, and rope drag, I wondered if I was even on the same climb.

In 1987—the year that Dave really immersed himself in climbing—he made yet another quietly impressive tick, onsight free soloing the North Ridge of Mount Stuart, a long, complex, technical rock route on the massive granite peak in Washington State. At the time, Stephanie was only three weeks old, and Dave and Nancy had hiked into the Stuart area with their newborn daughter. Wrote Dave, “What I remember from that day is the sun blazing in a brilliant blue sky, the hyper-white glare of glacier snow, and the swift upward movement over solid rock exposed on all sides.”