A Consolidated History of Women’s Climbing Achievements

From the first women recorded in mountaineering in the late eighteenth century, to the first 5.15 female ascent by Margo Hayes in 2017.

Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

For centuries, women have pushed their limits in the mountains. For nearly as long, they’ve done so behind the scenes and rarely received proper credit, being recorded as “Sir William’s Wife” or left unnamed. And when a woman did summit, it wasn’t due to her own strength but—as the narrative often went—to the men on her team who surely carried her across crevasses, hauled her pack, and held her hand on the most daring precipices. Women have persisted, though. Since women were recorded in mountaineering in the late eighteenth century, to the first 5.15 female ascent by Margo Hayes in 2017, the call of the mountains has been as strong for women as it has been for men.

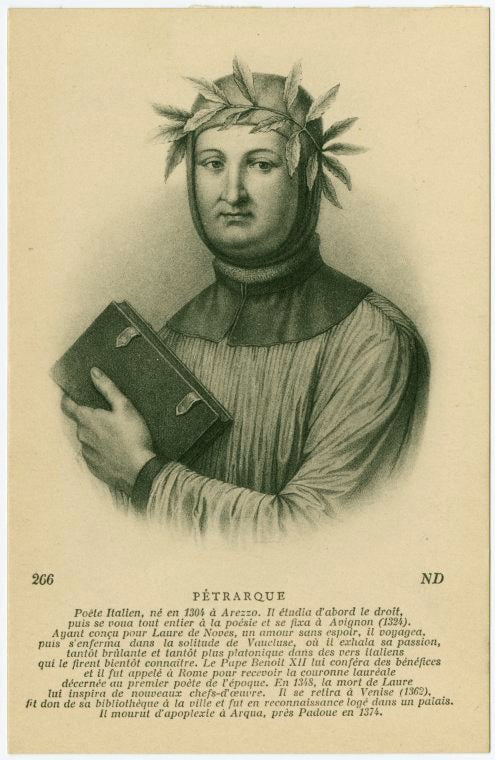

1799: The Beginning

Although the first documented ascent of a mountain was Mount Ventoux in 1336 by the Italian poet Petrarch (above), the first recorded female ascent wasn’t until 1799, when the mysterious Miss Parminter climbed “on” Le Buet (10,157 feet) in the Alps of Savoy. Shortly thereafter, in 1808, Marie Paradis became the first woman to climb Mont Blanc. However, her ascent went widely unknown. Thus 30 years later, French aristocrat Henriette D’Angeville, outfitted with six porters, six guides, and a 14-pound outfit including multiple layers, a petticoat, and a feather boa, summited Mont Blanc and proclaimed herself the first woman to do so. She did this with flare, releasing a carrier pigeon and popping open champagne on the summit.

1800s: Walker and Brevoort

Lucy Walker, rumored to have lived on sponge cake and spumante, became the first woman to summit the Matterhorn, in 1871, after hearing that her contemporary Meta Brevoort planned to snag the FFA. At that time, Brevoort was known for her “scandalous” fashion choices, often choosing pants over skirts on her ascents. Walker would go on to complete 98 expeditions and became an involved member of the Ladies Alpine Club, created in 1907 in London as a response to Britain’s strict “male-only” Alpine Club.

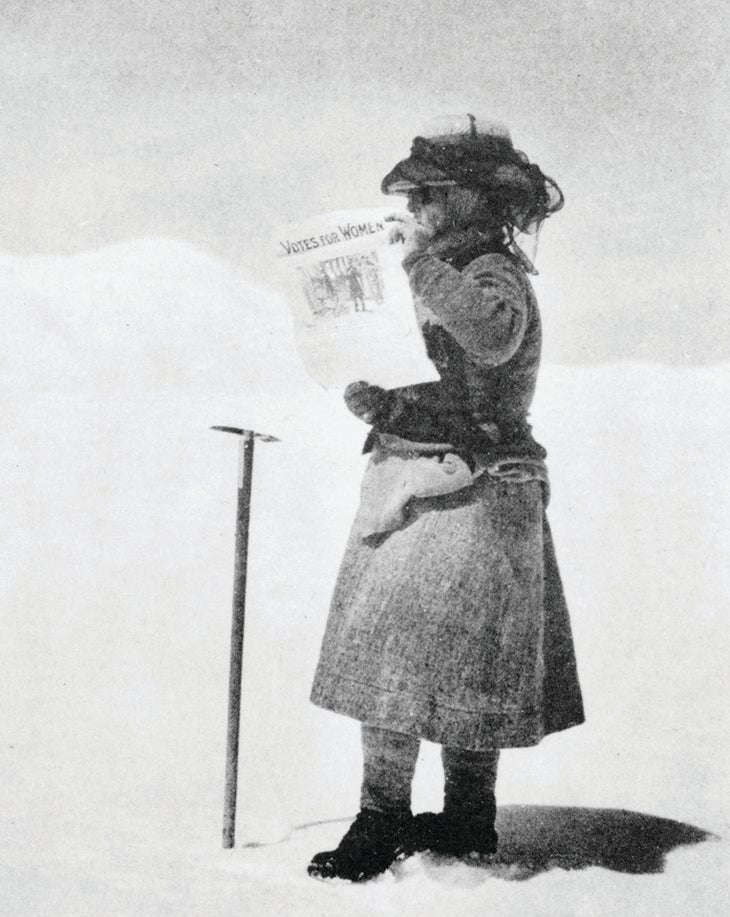

Late 1800s/Early 1900s: The Right to Vote

During the late 1800s, when women were getting their start in alpinism, men began rock climbing in the Elbsandstein of Saxony, the Lake District of England, and the Dolomites. While OG Jones was making his 1897 FA of the Lake District’s Kern Knotts Crack (5.8 PG-13), women were thinking of the right to vote. Annie Peck, a founding member of the American Alpine Club, climbed Coropuna (21,079 feet) in Peru in 1911, and waved a banner atop the summit reading “Women’s Vote.” Meanwhile, Fanny Bullock Workman, while surveying glaciers on an expedition in the Karakoram, was photographed with a “Votes for Women” sign (above). (Workman trekked to the Himalayas to climb Pinnacle Peak [22,735 feet] in 1906, establishing a new female altitude record.) Through the efforts of Workman, Peck, and countless other suffragettes, women won the right to vote with the ratification of the 19th amendment on August 18, 1920.

1920s: Miriam O’Brien Underhill

In the mid 1920s, Miriam O’Brien Underhill made the traverse from Aiguilles du Diable to Mont Blanc du Tacul, tagging five 4,000-meter summits. In the late 1920s, she coined the term “manless climbing” and in 1929 nabbed the first such ascent of the Grépon with Alice Damesme. Shortly after the ascent went public, the French mountaineer Étienne Bruhl infamously shook his head and stated, “The Grépon has disappeared. Now that it has been done by two women alone, no self-respecting man can undertake it. A pity, too, because it used to be a very good climb.”

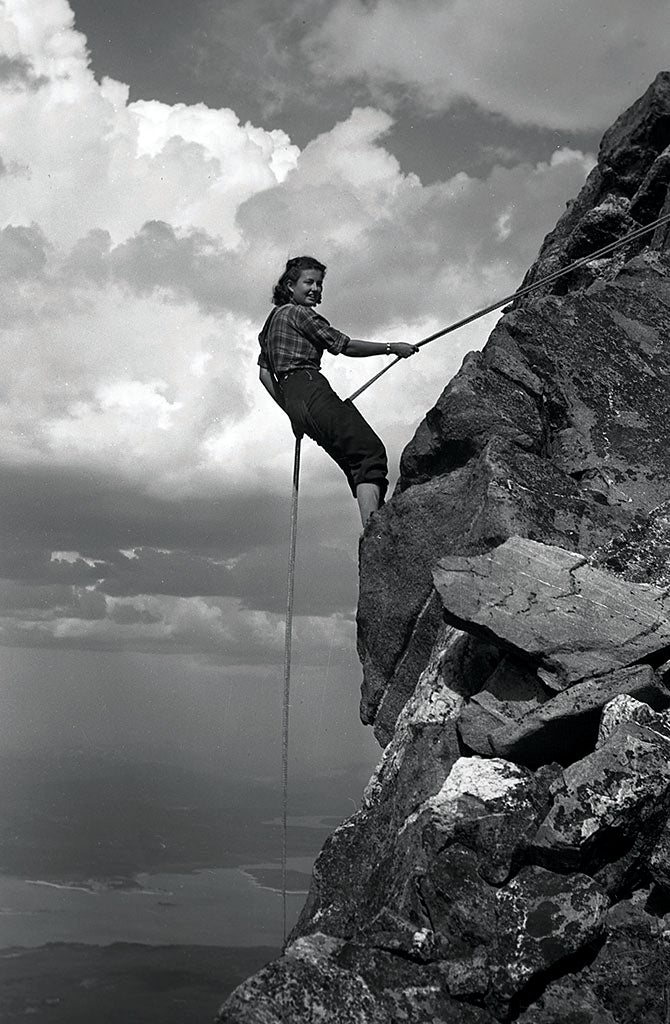

1930s: The Owen-Spalding

Negative sentiment toward women is easily found throughout our history in climbing, including in America. In 1939, a group of women from Jackson Hole, Wyoming, made the first female ascent of Owen-Spalding (II 5.4) on the Grand Teton. Margaret Smith Craighead (above), Margaret Bedell, Ann Sharples, and Mary Whittemore awoke earlier than other climbers to ensure critics couldn’t attribute their victory to the help of men. After their milestone, the Salt Lake City Tribune reported, “Another successful invasion of the field of sport by the weaker sex.”

1930s: Marj Farquhar—“Strong Like Lhotse”

Thankfully, the slights women climbers endured only solidified their goals. Like Marj Farquhar, who became the first woman to send Yosemite’s Higher Cathedral Spire in 1934, via its Regular Route. Farquhar, an active member of the Sierra Club, belonged to a small group of climbers who learned modern rock-climbing techniques from Robert Underhill, who imported them from Europe. Marj and her husband, Francis, were leading environmental activists in the mid-1900s, and remained at the epicenter of Yosemite’s early climbing years. “If people were mountains,” wrote Nicholas B. Clinch in his “In Memoriam” article, published in the 2000 American Alpine Journal, “Marj Farquhar would be Lhotse… strong, impressive, and rising far above most other mountains.”

1940s-’50s: WWII, Washburn, Prudden, and the Stanford Alpine Club

In the 1940s and ‘50s, World War II and its aftermath demanded everyone’s attention, and climbing came to a near-standstill. In 1947, Barbara Washburn became the first female to summit Denali (20,320 feet), and Bonnie Prudden became prominent in the Shawangunks, putting up some 30 FAs, including Bonnie’s Roof (5.9) and Boston (5.5 PG-13). The Stanford Alpine Club made their debut in 1947, with a nontraditional stance, welcoming women and celebrating “manless” climbing. Mary Sherrill, Freddy Hubbard, Irene Beardsley, and Sue Swedlund all made notable first all-female ascents of climbs like the Regular Route on Higher Cathedral Spire (Sherrill and Hubbard) and the North Face of the Grand Teton (Beardsley and Swedlund).

1960s: The Golden Age and The Feminine Mystique

The 1960s ushered in the Golden Age of Yosemite Valley. In 1967, Liz Robbins, along with her husband, Royal, ticked the Regular Northwest Face of Half Dome, becoming the first woman to climb a VI big wall (photo above shows them on the summit after their climb). Liz also attempted the Nose in 1967 with Royal, but the pair rappelled after 600 feet due to heat and insufficient water. In 1971, Johanna Marte became the first woman to scale El Cap—as a non-leading client of Royal Robbins. The 1960s also introduced Betty Friedan’s book The Feminine Mystique, which inspired thousands of women to find fulfillment beyond the role of housewife. Until its release, women spent 55 hours per week on chores and child-rearing, and less than 10 percent of all doctors, lawyers, and engineers were women. The women who pursued climbing were on the fringe of an already-fringe society. They rejected cultural norms, put off children, and pursued life with their own sense of purpose.

1970s: First All-Female Ascent of El Cap

Riding the wave of nonconformity that began in the 1960s, Beverly Johnson (above, at Camp VI) and Sibylle Hechtel made the first all-female ascent of El Cap via the Triple Direct (VI 5.9 C2-), in 1973. After seven days of learning how to haul bags that weighed more than both of them, throwing themselves into a sea of granite, and mustering every ounce of grit they had, the two topped out the 2,900-foot behemoth. While the women were on the wall, Valley climbers wagered for and against them. Their ascent marked a turning point for female climbers. Around this time, in 1972, Title IX became law, making sports equal opportunity for men and women. Prior to its passing, only 294,015 girls nationwide participated in sports. According to the 2015-2016 survey by the National Federation of State High School Associations, that number has grown 1,030 percent to 3,324,326 female participants.

1970s: Beverly Johnson and Ellie Hawkins, Yosemite

Soon after the Triple Direct, Johnson soloed the Dihedral Wall (VI 5.8 A3), while Ellie Hawkins soloed multiple Yosemite climbs including Never, Never Land (VI 5.9 A3) and the first ascent of Dyslexia (VI 5.10d A4), so named to bring awareness to a condition she’d battled her whole life. According to a 1985 LA Times article, while Hawkins soloed Dyslexia she “began to see in mirror images, and her shoelaces and her rope momentarily disappeared from her field of vision.” In 1977, Molly Higgins and Barb Eastman made the first all-female ascent of the Nose.

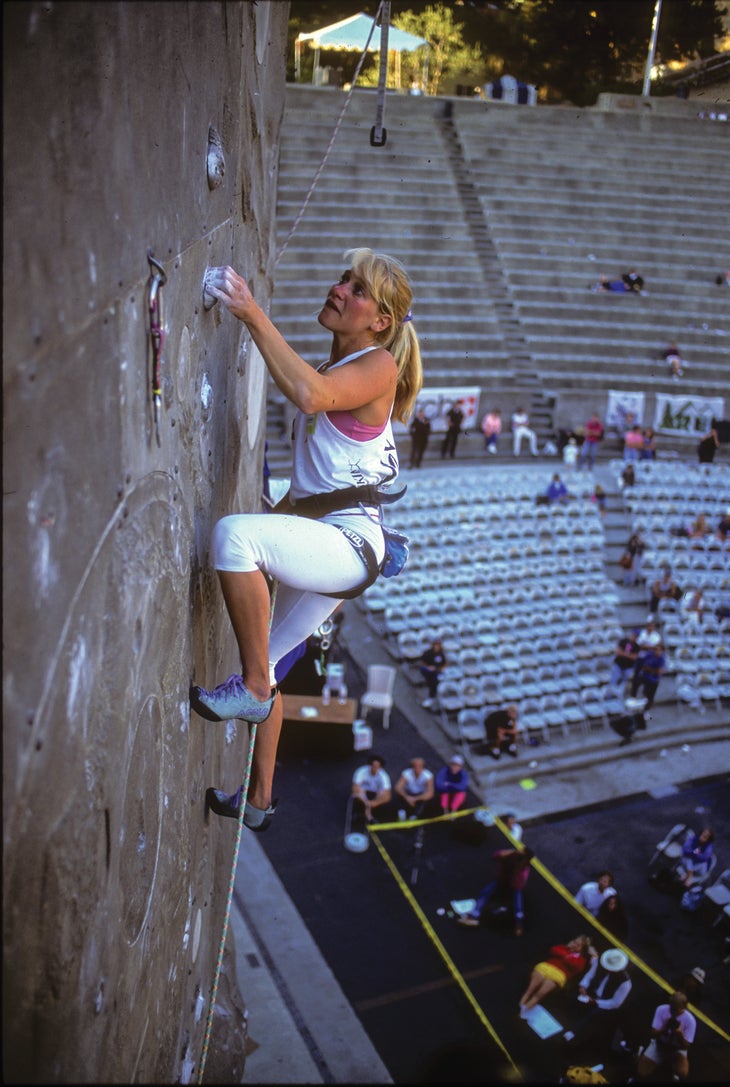

1980s: The Comp Era Begins; Women Tick Hard Sport Routes

The 1980s brought a new spin: competitions and indoor gyms. In 1985, the first SportRoccia event was held in Bardonecchia, Italy (it later became the Rock Master comp), and Catherine Destivelle, known previously for alpine climbing, took first place. A year later, Lynn Hill learned about the competition while climbing in France, and returned to enter. In a “disputed ruling,” Destivelle retained her position on the podium, while Hill, overwhelmed by the changing rules and regulations, took second. The two remained close competitors until Destivelle returned to alpinism in the 1990s. During this era, it finally felt like women were receiving their proper due. Luisa Iovane, and Italian climber, entered the competition circuit and climbed Comeback (5.13b; above) in 1986. And Isabelle Patissier sent Sortileges in 1988, becoming the first woman to climb 5.13d.

Early 1990s: Lynn Hill Climbs 5.14 and Frees the Nose

In 1990, Lynn Hill became the first woman to redpoint 5.14a with Masse Critique in Cimai. Hill’s passion for the sport and progression through the most difficult grades landed her on talk shows, and made her a crowd favorite at competitions. Hill had come to Yosemite Valley in 1978 as a 17-year-old, and quickly gained a spot under the wing of the Stonemasters, a group of freewheeling climbers from Southern California. She found a climbing partner in Mari Gingery, and in 1979, the pair completed the first female ascent of The Shield (V 5.8 A3) on El Cap over six days. Hill has many other noteworthy firsts including Vandals, a 5.13a trad route in the Gunks, along with her 1993 free ascent of the Nose (VI 5.14a), where she famously pronounced, “It goes boys!” Hill then returned in 1994 to free the route in a day.

Mid-1990s: Robyn Erbesfield-Raboutou Crushes All Comps

In the mid-1990s, Robyn Erbesfield-Raboutou won four World Cups in a row and became the third woman ever to send 5.14, a feat she continues to accomplish in her 50s with ascents of Philipe Cuisinere (5.14a) in 2016 and Thunder Muscle (5.14a) in 2017. She also won every competition she entered in 1993, as well as five US championships in her time as a competitor. Now she’s raising her children under the wing of Team ABC, part of the ABC Kids Gym, a bouldering and training facility she founded with her husband, Didier, in Boulder, Colorado. Their daughter, Brooke, 16, has sent V13, and is the youngest person to climb 5.14b with her ascent of Welcome to Tijuana, in 2012 at 11 years old.

Mid-1990s: Third Wave Feminism; Women Shred in Droves

The Family and Medical Leave Act in 1993 and the Gender Equity in Education Act in 1994 allowed women to stand up for themselves in education and at work. Women’s numbers in the Senate doubled, Janet Reno became the first female Attorney General, and Ruth Bader Ginsburg became the second woman appointed to the Supreme Court. Meanwhile, women worldwide were working to abolish gender stereotypes and role expectations, creating the “third wave” of feminism. In climbing, the rise of gyms and competitions ushered in a major uptick in women climbing hard. In 1996, Mia Axon became the fourth woman to redpoint 5.14 with Planet Earth (5.14a) in the Virgin River Gorge. And in 1999, Katie Brown became the first woman to onsight 5.13d with Omaha Beach in the Red River Gorge at age 18, after mistaking the new climb for a 5.12 warm-up.

Late 1990s-Early 2000s: Josune Bereziartu and 5.14+/15-

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the Basque Josune Bereziartu became the world’s best female sport climber. After encouragement from friends to become the first woman to redpoint 5.14b, Bereziartu began projecting Honky Tonky in 1997 and succeeded in 1998. She continued to break records, becoming the first woman to redpoint 5.14c, 5.14d, and 5.14d/5.15a with Honky Mix (2000), Bain de Sang (2002), and Bimbaluna (2005), respectively. Bereziartu’s ascents dramatically narrowed the gap between men and women, and by the late 2000s women were climbing 5.14 in numbers never seen before.

Mid-2000s: The Art of the First Ascent

One of the most impressive things women have been doing in ever greater numbers since Lynn Hill freed the Nose is cutting-edge first ascents. In 2004, Beth Rodden established The Optimist, a 5.14b seam in Smith Rock. Then, in 2008, she redpointed her 40-day project Meltdown, a 5.14c trad climb that became the hardest pitch in Yosemite at the time. Meltdown has remained unrepeated despite attempts from numerous strong climbers. Other examples of hard recent female FAs include Utah climber Jacinda “JC” Hunter’s 2010 route Fantasy Island (5.14b) in American Fork—completed while raising four kids and working full-time as a nurse; Paige Claassen’s 2013 FA of Digital Warfare, a 5.14a sport climb in South Africa (above); Isabelle Faus’s FA of The Dark Daughter (V13) in 2016 in Rocky Mountain National Park; and Barbara Zangerl’s 2017 first free ascent, with Jacopo Larcher, of Gondo Crack (5.14b) in Switzerland.

2010s: A New Era—Sasha DiGiulian, Ashima Shiraishi, and Margo Hayes

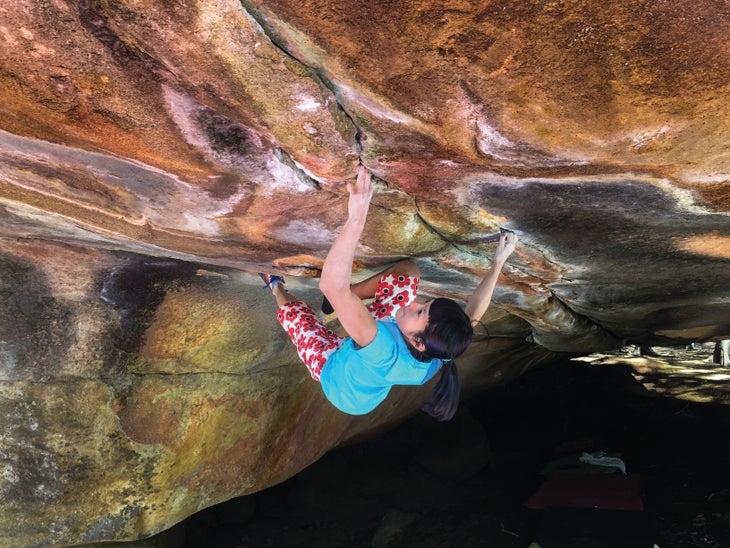

In the late 2000s to present day, the gap between men and women has narrowed to a sliver. In 2011, Sasha DiGiulian became the first American woman to climb 5.14d with her ascent of Pure Imagination (later downgraded to 5.14c), and in 2013 became the first female up the adventurous Bellavista (5.14b), a multi-pitch climb in the Dolomites. DiGiulian, who stands 5’2” and sports long blonde hair and pink fingernail polish, works to dispel the idea that women who play outside are tomboys. Ashima Shiraishi, often outfitted in bright, patterned leggings made by her mom, also belies this idea. On March 22, 2016, at Mt. Hiei, Japan, Shiraishi, became the first woman, and youngest person (then 14), to top out a V15 boulder problem with Horizon (above). Then, in February 2017, after seven days of projecting, Margo Hayes made sport-climbing history when she clipped the chains on La Rambla (5.15a), becoming the first female to climb the grade.

[Ed. Since this story ran in our September print edition, Anak Verhouven put up a 5.15a first ascent, and Angy Eiter became the first woman to climb 5.15b!]

Only a hundred years ago, women were fighting for the right to vote. And while we’re currently experiencing political turmoil over women’s rights—among many other issues—in our country, there’s no denying we’ve come a long way. Today’s crushers like Alex Puccio, Emily Harrington, Paige Claassen, Hazel Findlay, Nina Williams, Michaela Kiersch, and so many more will continue to push the limits of what’s possible for women. If we’ve come this far in a hundred years, what will the next hundred bring?

Megan Walsh is a climber/writer in Salt Lake City. She loves exploring routes in Utah and beyond, but is even more stoked about furthering the progress of women in the outdoors.