David Roberts, Adventurer, Climber, Author, Dies at 78

David Roberts, in center in white, on the summit of Denali after a new route up the Wickersham Wall, in 1963. (Photo: David Roberts collection)

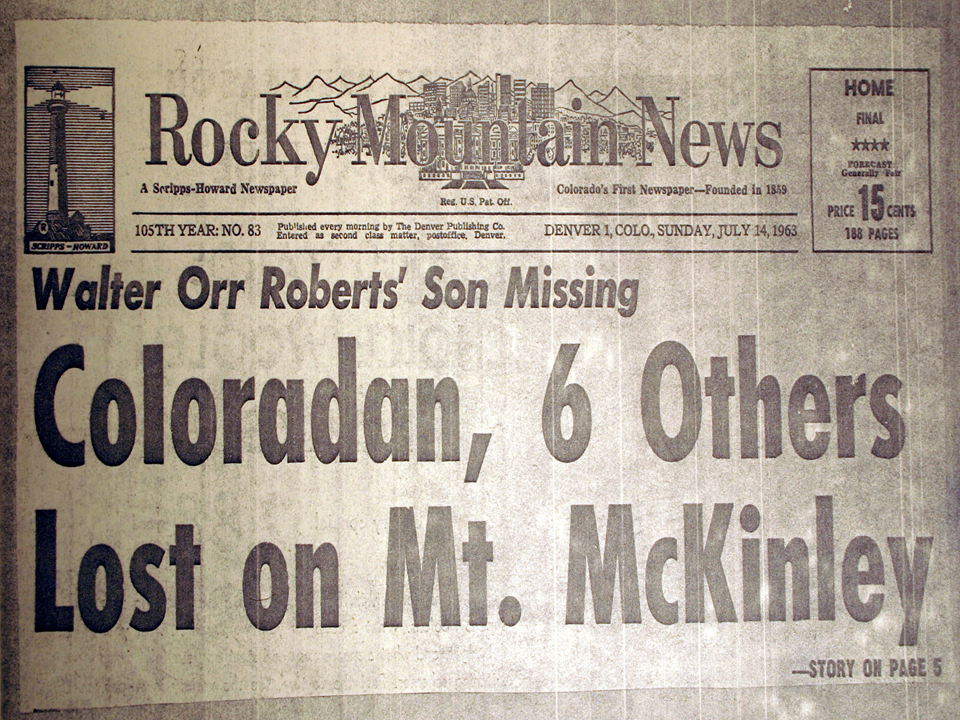

David Roberts, explorer, climbing pioneer and prolific author, died on August 20 from complications following his six-year battle with throat cancer. He turned 78 this past May. Roberts leaves a master-class body of work in the mountains, across the desert Southwest, and in written words. His important first ascents are as innumerable as his books and articles. In Alaska he racked up “20 or 30” firsts, including a new route on Denali’s massive Wickersham Wall in 1963. During that ascent, after Roberts and team were out of touch for five days, Rocky Mountain News reported the team missing and feared dead.

“Nonsense,” said Bradford Washburn, the photographer and cartographer who had talked Roberts into the Wickersham. “Five days out of touch is nothing. Those boys know what they are doing.”

Most climbers will know Roberts for his books, especially Mountain of My Fear, which he pecked out in a blistering nine days while on spring break during graduate school at the University of Denver. That book, about the 1965 first ascent of The Harvard Route on Mount Huntington and the death during the descent of his friend Ed Bernd, became an instant classic, deserving a place beside Lionel Terray’s Conquistadors of the Useless, Tom Patey’s One Man’s Mountains, and Heinrich Harrer’s White Spider.

Roberts didn’t plan on becoming a writer. He studied math at Harvard, but decided he preferred musical composition. A family friend, a composer, kindly told him he should try something else and suggested writing. Turned out he was quite good at it, possessing a curiosity and precision that provided a scientific depth to his works. Roberts admitted that he became an “obsessive writer.” He authored 32 books and hundreds of magazine articles including many for Rock and Ice, Ascent, Climbing and Outside. His latest work, The Bears Ears: A Human History of America’s Most Endangered Wilderness, hit bookshelves in February.

Roberts began climbing in Boulder, where his father, Walter Orr Roberts, an astronomer and atmospheric physicist, founded the National Center for Atmospheric Research. On an early outing in 1961 the young David’s friend Gabe Lee fell to his death when he downclimbed, unroped, to retrieve their jammed rope on the Third Flatiron. Gabe’s death haunted Roberts. When Ed Bernd perished on Huntington without uttering a word as Roberts watched, Roberts had to face the family and recount what had happened. “They looked at me with blank faces,” he wrote in Moments of Doubt. “‘My poor baby,’ Mrs. Bernd wailed at one point, ‘he must be so cold.’”

At age 22 he considered quitting climbing. Is it worth the risk, he wondered?

That answer would come 25 years later when he wrote On the Ridge Between Life and Death. The answer was “maybe,” and in an interview this spring for Climbing, he said he still stuck to that realization, adding that while climbing had for almost 20 years been “the most important thing in my life … life is too precious to throw away.”

Like many climbers past their prime, Roberts phased out of climbing, in his case by age 35. “I started to think that I’d been pretty damned lucky to survive my close calls, and that I wasn’t likely to get any better at climbing in the coming decades,” he told Climbing.

In 1992 while reporting on an archaeological team’s work on ancient Puebloan sites in the desert Southwest, Roberts found his replacement for adventure in the mountains. He spent summers and autumns exploring the canyonlands, studying rock art and ruins to try and determine how The Ancient Ones—the Anasazi, Mogollon and Fremont—had lived, why they had been there and what had happened to them. Climbing, he would tell Harvard Magazine in early 2021, had focused on “me,” while studying The Ancient Ones was all about “them,” and sharing what he learned in the desert was as gratifying as first ascents.

Share he did, writing six books on the subject including The Pueblo Revolt; Sandstone Spine, Seeking the Anasazi on the First Traverse of the Comb Ridge; and Lost World of the Old Ones: Discoveries in the Ancient Southwest.

In 1966 Roberts began dating Sharon Morris, a fellow student at the University of Denver. He asked her if she’d spend a summer with him in Alaska. Yes, and a year later the two were married and remained together until the end.

During that stint in Alaska, Roberts connected with fellow alpinist Art Davidson, who would later write Minus 148 Degrees, a book about the first winter ascent of Denali (then known as Mount McKinley). With Davidson and other fellow climbers from Harvard, Roberts opened climbing in the Revelation Mountains and even named them, spending 52 days with no contact to the outside world in the westernmost extent of the Alaska Range.

Fifty years later Roberts lamented that today’s technology had made it nearly impossible to find real adventure, to really put yourself out there when help is just a text away. In “Our Loss,” he noted that he, too, was part of an evolutionary journey, that by the time he explored in Alaska he had a plane to fly him in, while the old timers had had to walk or boat in. “I suppose we all know in some vague way the old-timers were tougher than we are, made do with gear we’d sneer at, had an infinite capacity for hard work and suffering,” he wrote. “Back then, it didn’t matter when you got home.”

In the interview “Is Climbing Worth Dying For?” Roberts said that if he were young today he’d probably become a caver, because the world’s deepest places had yet to be plumbed and they are where the adventure is. Cavers, he said, aren’t “competing for new lines five or 10 feet left or right of existing routes, but for tubes and shafts and amphitheaters no one has ever seen before, spangled with fragile, unworldly ‘speleothems.’ Those cavers exude wonder. How much wonder do you run into nowadays at Rumney or the Red or Eldorado?”

When Roberts was diagnosed with throat cancer in 2015 he seemed to turn more inward, soften. He became a bit easier to work with on edits, and fretted like a mother when younger climbers such as Clint Helander went off to Alaska to attempt dangerous climbs. “If Clint or Michael [Wejchert] were killed in the mountains, not only would I be devastated,” he wrote in “Alaska Requiem,” “but it would in some sense call into question my faith that, after all, climbing is huge and ennobling and worth risking everything for, rather than crazy and stupid and tragic.”

Roberts wrote four books while he was sick, including Limits of the Known, where he explored man’s relationship with adventure and risk. His later works were “among my best.”

After a life of climbing, exploring the desert, and writing, Roberts faced the big unknown. Not one to “put stock in the old fairy tales of heaven and an afterlife,” he said, “leaving this planet will be the hardest thing I’ve ever done.”