Dirtbagging in the Time of COVID-19

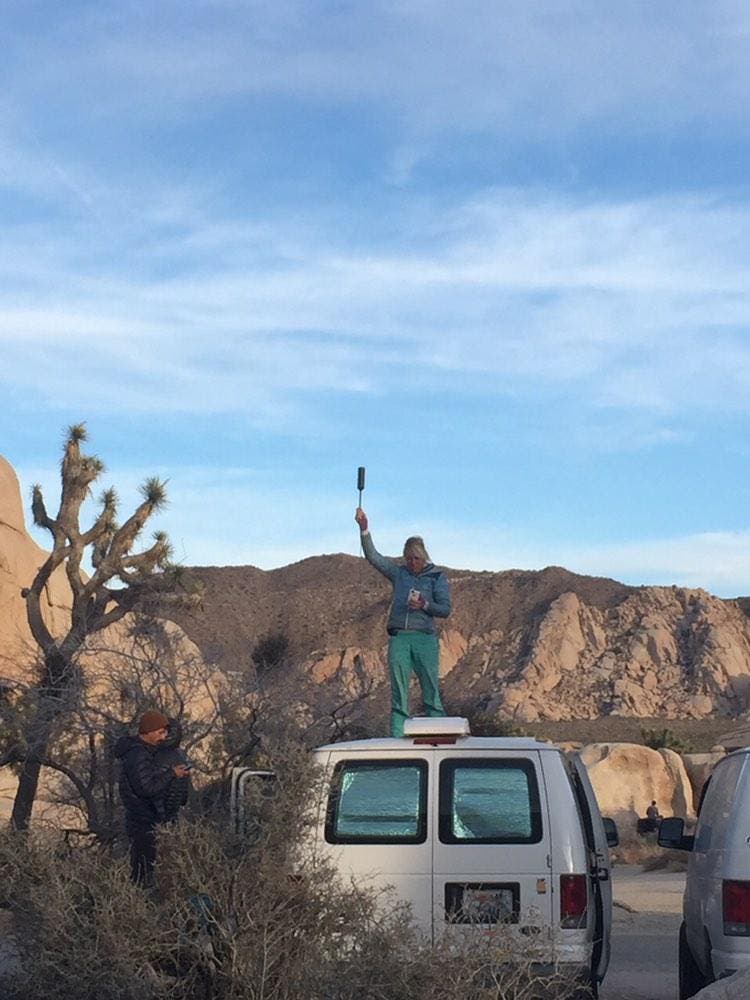

"Courtesy Brittany Goris" (Photo: Courtesy Brittany Goris)

“Stay home.”

With the Coronavirus spreading like wildfire, the message is coming at us from every angle—from the government, climbing media, outdoor companies, pro climbers, our peers, etc. Climbers everywhere have answered the call to “go home,” and hunkered down to wait out the viral storm. Still, within our community there exists a subculture of climbers who live in cars, vans, or amidst the boulders, for whom the act of “going home” is a meaningless order. Where is home for someone who travels full time?

The idea of the American dirtbag climber is a romantic picture, but once the layers get peeled away the van-lifer is technically just a homeless person, albeit by choice rather than circumstance. They’ve sacrificed the security of a home in favor of the vivid pursuit of their dreams, with the acceptance that there is inherent risk with their lifestyle choice—the risk that if things go sideways there might not be an easy, comfortable, or safe fallback option.

This winter, things have gone sideways and then done a full 360, leaving nomadic climbers such as myself stranded and scared. Those home on the couch have been quick to take up the call to arms against anyone out climbing in these times of crisis, shaming travelers, telling them to avoid climbing towns, and saying what we’ve already heard from everyone else: go home.

My van is my home, as it is for many others. Most of the time that means I can go anywhere and feel at home, but when the world is shutting down to flatten the curve of COVID-19 it feels like the opposite: that nowhere is home.

Is home where you grew up? Going home could mean returning to a parent’s house. That’s where my mail goes. I could technically call it home, but that doesn’t mean I can go there. My parents are both over 60, and one of the highest risk groups for COVID-19 is the elderly. Even the youngest dirtbag climbers likely have parents in this category, and potentially bringing the virus to this home could endanger the life of a loved one. Parents’ homes are also often in far reaches of the country or even abroad, inaccessible without a significant amount of travel. My hometown in Fort Collins, Colorado, is at least a 30-hour drive from where I am writing this in California.

Is home where you work? Most full-time climbers have based their lifestyle around some kind of employment, yet it’s rarely the traditional idea of work nor does it offer a solution. Many work seasonal jobs at places like ski resorts or summer camps, which are being closed. Others, like myself, work remotely and rely on libraries or cafes for internet and electricity, which are also getting shut down left and right. My company is based in Seattle. I could call that home, but the last time I parked outside the office my car got stolen—not to mention that Seattle is ground zero for the outbreak, so every friend I have there is either sick or probably carrying the virus. Another non-option.

Is home where you spend the most time, or feel the strongest sense of place? Many climbers consider their favorite climbing areas home, as they make seasonal pilgrimages to places like Indian Creek, Yosemite, Smith, the Red River Gorge, etc. These are the best options myself and many others have, yet these small communities insist that travelers are unwanted and have adopted a locals-only attitude to protect themselves from the “extended spring break” attitude toward COVID-19.

I, like many others, chose a van-dwelling dirtbag lifestyle because I love climbing more than anything and want to pursue it with all the passion and dedication I’ve got. I need climbing more than I need the stuff that fills a house. My home is wherever I climb. I also chose this life so that I could be a professional climber, which puts me in a position where my decisions set an example for others. My sponsors tell me to promote ways to train from home to encourage others not to go out. I was even given a hashtag to use for my in-house training, yet I’m only in a house at the moment because my van is in the shop; a haven with an expiration date. Even heading for the wilderness alone or with a small group for self-isolation is dangerous, because if the sickness were to hit hard, medical attention would be far away, if possible at all.

Thus, the nomads like myself face a moral dilemma with no easy answers in this time of crisis: Our presence poses a risk to any place we might consider “home,” or that place poses a risk to us. So, what’s a dirtbag to do?

Times are hard, but dirtbags are a crafty and resourceful bunch. We’re used to finding ways to make things work in even the grittiest circumstances. Eating nothing but beans for days on end or pooping in a bag isn’t a tall order for a climber. We’ve been unintentionally preparing to survive a catastrophe since the beginning of our sport. Thus, this isn’t a cry for help, but for understanding. We are all struggling to do the right thing to protect the people and communities we love. As bleak as it is to face voluntary house arrest, it’s bleaker still to feel unwanted or unsafe in the only places we can think to go, or even that our presence might be harmful. It’s essential that everyone do their part to flatten the curve of the coronavirus outbreak, so yes stay home if you can. Yet as things get darker in the weeks to come, it is also important that the climbing community protects not only our climbing areas, but the people who call them home. Adopt a stray dirtbag if you can, but at the very least, in the face of this crisis, we must support each other and stand together… six feet apart; I don’t want your germs.