Escalando Fronteras: Helping At-Risk Youth in Mexico Through Climbing

"None"

Veronica screams as Tiffany Hensley cleans the cut across the back of her thigh. A man stumbles toward us in front of Veronica’s cinderblock home in the Lomas Modelo neighborhood of Monterrey, Mexico. Hungry dogs and barefoot kids loiter on the dirt road below, and the sweet smell of burning trash lingers in the air. Beads of sweat glisten on the man’s forehead. His nostrils and mouth are cracked and white as he slurs like a motorcycle changing gears in slow motion. The children standing around us point at the man, repeating, “¡Zombi! ¡Zombi! ¡Zombi!”

Unfazed, Hensley, 26, the operations director of Escalando Fronteras (EF)—an organization in Monterrey that takes at-risk youth rock climbing—continues cleaning the wound. Six-year-old Veronica scraped her leg playing. In Lomas, the kids go weeks without bathing, and lack money for Band-Aids or Neosporin. A cut can quickly become infected. Veronica is one of about 30 kids from the colonia of Lomas involved with EF, and is also one of the most vulnerable. Her mother works as a prostitute, spending nights downtown, leaving Veronica and her four siblings alone at home to cook and fend for themselves, sometimes for days at a time. They rarely go to school.

Cinderblock homes and cement stairs cover the hillside of Lomas. Rural immigrants, known as paracaidistas—“parachuters”—built these structures without permits when they traveled here from southern states such as San Luis Potosí. Many are Indígenas who speak Otomí—a group of languages spoken by indigenous Mexicans. Because of their language barrier, early school desertion, and low socioeconomic status, these immigrants have had a hard time transitioning into city life. They remain on the fringes, poor and without work. Craggy limestone peaks loom in the distance, blurred by smog. Monterrey is a hub for climbing, surrounded by the internationally acclaimed limestone areas Potrero Chico and El Salto, and lesser-known Parque la Huasteca.

Veronica’s uncle, the “zombie,” is high on tolueno—paint thinner. In Lomas, high rates of unemployment contribute to rampant drug and alcohol abuse, and tolueno is cheap and easy to come by. Hensley encouraged the kids to compare the addicts to zombies as a scare tactic to keep them away from tolueno. A lot of the kids in EF have family members or friends who use and sell, so there isn’t much incentive to stay away, making young people in these communities vulnerable to using.

Hensley finishes her makeshift bandage, and Veronica limps toward her house before turning back to us. “¿Puedo escalar el Domingo?” she asks: “Can I climb on Sunday?”

“Welcome to Mexico!” Hensley says as she steps out of her Sprinter van at the Monterrey airport on a Wednesday afternoon in February 2017. New York received a blizzard warning the day before, and now I’m squinting in the hot Mexican sun. I barely recognize this boisterous and sun-kissed human. She hauls my suitcase over the seat, explaining that the side door is broken.

Hensley and I both climbed at Pacific Edge Climbing Gym in Santa Cruz, California. It was the 1990s, and we were at the tail end of the first generation of gym rats. I was a few years older than Hensley, but we both lived at the gym. Hensley rarely talked, opting instead to lap the freestanding boulder in the front. She spent most of the time lurking on the sidelines, neck slightly hunched, watching as bros hucked themselves at boulder problems. She would wait for them to give up, and then slink up to the wall, hands chalkless, and casually send whatever they were working on, the faintest smirk on her face as she walked off without a word.

After high school, Hensley immersed herself in climbing. She moved to Boulder, Colorado, competed in open competitions internationally, worked as a team manager, and then decided to travel. She took to the road, living out of her van. “I was looking for something larger than myself,” Hensley says.

Inspired by Professional Climbers International (PCI), clinics put on by professional climbers for young up-and-comers, Hensley wondered if the same model could be used with at-risk youth. After visiting Climb & Conquer in Vancouver, Canada, a charity organization teaching at-risk youth how to rock climb, Hensley contacted the American climber Rory Smith, co-founder of EF. She asked him what he thought of bringing pro climbers to their young initiative, which Smith had helped launch as a pilot program in March 2014. “He was stoked,” Hensley says, so in February 2014 she headed across the border to visit EF firsthand.

Walking through Lomas for the first time, Hensley couldn’t believe the conditions the kids were living in. A few months later, she started teaching English in Monterrey so she could stay indefinitely. She traveled back to the States and raised $10,000 in gym holds, gear, and funds, using her connections in the outdoor industry. Now, as operations director for EF, she obtains gear from companies and oversees climbing excursions, ensuring that the kids and volunteers climb safely. After getting the thumbs-up to write about and shoot photos of EF, I had hopped on a plane with one week to learn about the program.

“I’m so glad you’re here,” Hensley tells me as we leave the airport and weave through a web of highways and cars. Her wide blue eyes shine with a familiar earnestness.

Monterrey is the capital of Nuevo León, a state in northeastern Mexico. The city has the highest per capita income in the country and is known for being a dynamic industrial center and international business hub—home to giants like Cemex (the third largest cement company in the world) and FEMSA (the biggest independent Coke bottler). As with so many cities, wealth is poorly distributed, creating massive economic disparity between the middle/upper classes and the lower class. While wealthy neighborhoods like San Pedro are brimming with luxury highrises, pristine parks, and Starbucks, informal neighborhoods like Lomas Modelo don’t even have paved roads.

Hensley pulls into a semi-industrial neighborhood and parks in front of a corrugated garage door. The familiar smells of chalk and feet greet us when we enter. The clean white walls of Delta Indoor Climbing Club look brand new. Hensley talks to Antonio, a 13-year-old hiding behind a mop of thick black hair who nods at me shyly. She asks him about Javier, another EF member who was supposed to be at the gym studying.

According to Antonio, Javier had shown up while Hensley was picking me up at the airport, claimed that she had his books, and left. She translates this to me, her arms crossed in front of her, and nods her head to a stack of books in the corner—Javier’s.

Javier has been with EF from the start. He was raised by his grandparents, who cared about him but were unable to watch over him properly. His dad, a tolueno dealer, got him involved in selling young, and before long he was using; Javier fell in with the wrong crowd and gained a reputation in the neighborhood.

“They’re good kids but they lie,” Hensley says. “They’re sneaky; they can talk themselves out of anything because they’ve had to, in order to survive.”

The next day, after an EF staff and volunteer meeting, we find a young man sitting slouched over a too-small bike outside the gym. His eyes hide under the shadow of his flat-brimmed baseball cap.

“Javier is here!” Hensley says. Javier greets me with the standard greeting of young people in Lomas: a sideways high-five to a light fist bump. I miss the bump, and he shakes his head, laughing.

In early 2014, Rory Smith completed his master’s thesis at the University of Lund in Sweden. He had studied youth and the motivators that led them to join gangs and cartels in Monterrey. Ultimately, he found that they resorted to drugs and violence as a means of survival—when you are surrounded by violence and substance abuse, and nobody expects you to do anything else, what motivation is there to say no?

Smith knew that sports and the outdoors had been proven to help keep at-risk youth out of trouble. Monterrey, with all its limestone, provided ample venues to climb. He contacted Dr. Nadia Vasquez, a Monterrey local and recent PhD graduate, after hearing her discuss her work with child soldiers in the Congo on a podcast. Smith thought that rock climbing, a sport historically only pursued by white foreigners in Monterrey, could be used as a tool to keep local kids out of the cartels and street gangs.

One week later, Vasquez and Smith talked to families in the barrio, gauging the feasibility of their project. In March 2014, they launched a pilot program of Escalando Fronteras in Lomas Modelo.

“We used to go up every Sunday and basically beg [the kids] to come climbing,” Vasquez remembers. Now, in their third year operating, they have about 20 kids who climb weekly and they’ve worked with about 100 total from the neighborhood.

“Sundays are the worst days,” Vasquez says. Most of the men in the neighborhood work low-paying menial jobs. When they finish working Friday afternoon, they start drinking together, and continue through the weekend. “By Sunday, they have been drunk for almost three days and they get violent. The women stay inside, hiding from their husbands,” Vasquez says. Vasquez and Smith designated Sundays as the day to bring kids climbing, to take them out of the neighborhood on this most perilous day of the week.

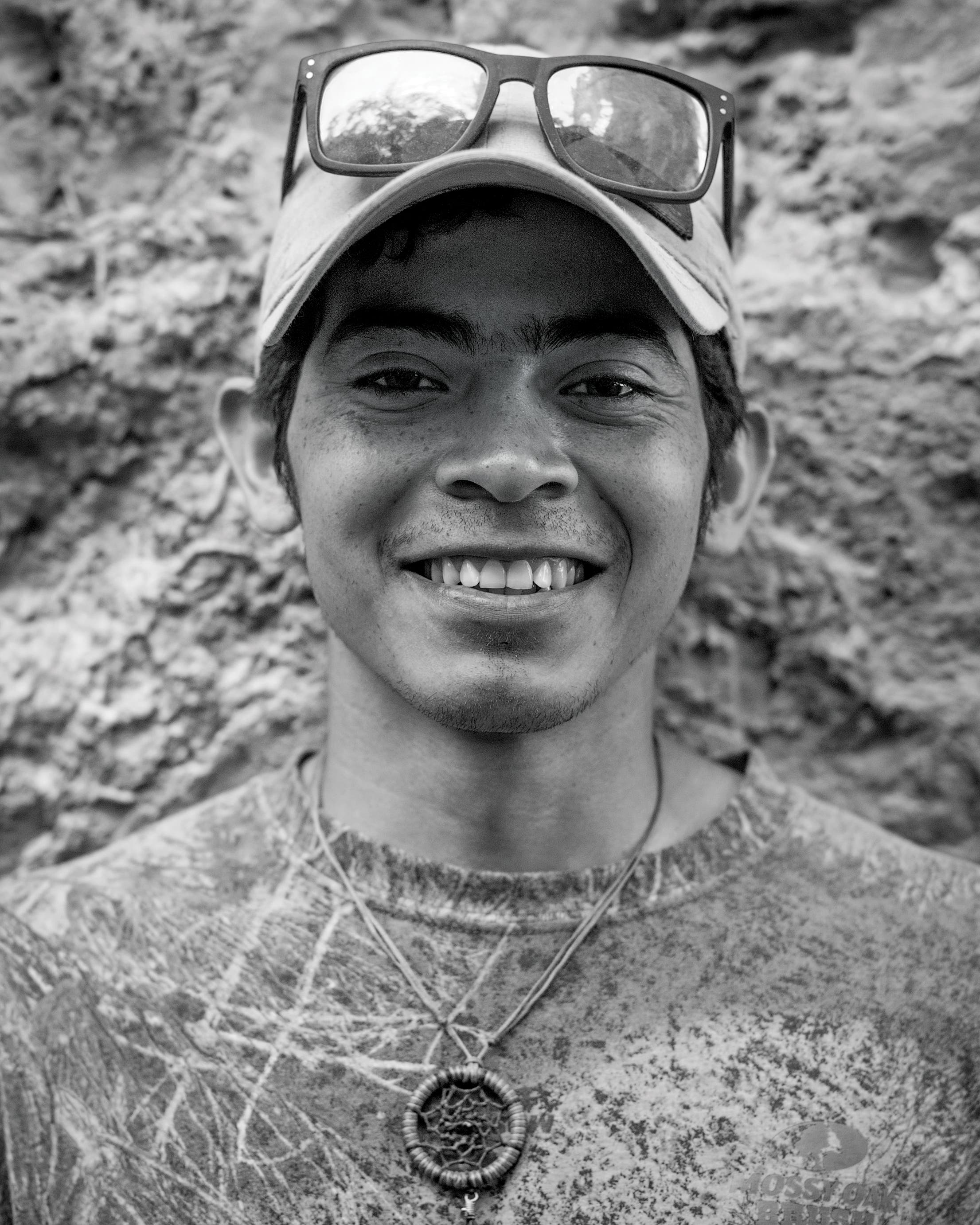

The Faces of Escalando Fronteras

Photo: Sasha Turrentine

The younger kids, ages 5 through 12, train two mornings a week at Casa de Piedra (CdP), a gym in southern Monterrey. After seeing the difficulties the older kids face engaging with the program, Hensley spearheaded a three-month pilot leadership program to encourage them to become more involved. Modeled after a youth organization she observed in San Diego, the program aims to have the kids engaged six days a week—be it studying, climbing, or picking up trash in Huasteca—culminating with a trip to Iztaccihuatl, a 17,000-foot volcano outside Mexico City. They study and then train Monday through Thursday at Delta, within biking distance of Lomas. Friday is for community-improvement projects—recently, Antonio suggested they plant trees alongside Lomas’s dirt road. Sundays, they help out with the climbing trip, mentoring and coaching the younger kids.

The younger kids have shown improvement, and a few of the older kids have stepped into leadership roles. One of the kids, Choko, competes in local competitions and boulders V5. He’s also been attending school more regularly and become a better student. Climbing has helped satiate the children’s listlessness and given them an alternative identity and a sense of purpose.

“Now, the kids prefer to be climbing with us than to stay [in Lomas],” Vasquez says, her stoic face lighting up in a smile.

In 2015, EF put together an Indiegogo campaign in hopes of raising $30,000 to build a gym for the kids in Monterrey. They raised about half that, most of it coming from individual backers and outdoor companies in the United States. While funds were inadequate to build a gym, it enabled them to cover operational costs for almost two years.

“Not having our own physical space has been the biggest barrier,” Hensley says, “but local gyms have been very accommodating.” All of Monterrey’s four gyms—CdP, Mad Complex, RockArt, and Delta—have offered their spaces to EF kids to train and study.

As Hensley and I hang out at Delta that afternoon, she explains the deal: If the kids study for two hours, then they can climb. Since my Spanish is embarrassing, I end up on babysitting duty, playing with 4-year-old David. Hensley helps his 16-year-old mother with her algebra homework.

“I know I learned this stuff, but it’s been a while,” Hensley says. “If we had the money, we could pay for proper tutors.”

In its infancy, EF’s mission was to get children outside and teach them to climb, to give them a healthier activity to replace drug use and the impulse to join cartels and street gangs. As the program progressed, it became obvious that the kids needed more than climbing. “A lot of these kids have dropped out of school. Their parents are too busy with work or their own problems to care,” Hensley says. EF has helped get a couple of the kids re-enrolled in school, and now enforces mandatory study time.

Not quite two hours have passed and Javier is putting his shoes on with Pedro, the oldest and most enthusiastic member of EF. “Pedro is our mascot,” Vasquez joked to me earlier in the day. I feel a bit intimidated. So far, my interactions with the kids have been limited by my lack of Spanish. The new volunteer, Everardo—who is a fluent Spanish speaker—and I decide to teach them the simple game of add-on.

Javier climbs well, deadpointing to holds with accuracy. I’m unsure if he’s giving 100 percent, but Pedro is. He’s light and lanky, and his enthusiasm and effort seem to buoy Javier. Soon we are all laughing as they try to throw each other with tricky moves. I am still recovering from a broken wrist, so I make up my own problem following jugs. I move across the wall using only my left hand until a dramatic botched dyno throws me to the ground. I get another fist bump, one from Pedro and one from Javier. This time, I don’t miss.

On Sunday morning, when we open Tiffany’s van door at the bodega at the base of Lomas, kids are shouting excitedly at one another and wrestling.

Vasquez shouts to maintain order, and the kids form a writhing assembly line. She counts off the first four giggling girls, and they shriek and leap toward the first car. There are a handful of volunteers, three of whom are mothers of kids in the program. “I realized quickly that we couldn’t do this without support from the mothers,” Vasquez says. A full-time professor at the Universidad de Monterrey, Vasquez spends her free time driving younger kids to practice twice a week and also spends a lot of time in Lomas, checking in with families and seeing what she can do to help. She is currently trying to find Veronica and her siblings a foster home.

We drive toward a newly developed bouldering area in Huasteca Canyon, about 30 minutes from Lomas. Huasteca is the less popular sibling to the famous El Salto and Potrero Chico crags, but offers over 300 sport routes and is a popular BBQ hangout spot for locals looking for an escape from the smog.

The van takes a sharp corner and cruises under a huge dam. The pavement ends as the van careers over potholes and small boulders. The kids hoot and holler in the backseat, heads bouncing. They know we’re getting close.

“Oh crap,” Hensley says as the kids pile out of the van at the boulders. “Javier and Pedro.”

The night before, we had dropped the boys off at a trailhead close by so they could camp in the canyon. “Pedro is obsessed with the mountains and adventure now. [His friends] say he has become an entirely different person,” Vasquez told me. The two of them told Hensley that they would meet her by the road in the morning so they could come help out.

Hensley and I hop back in the van. We drive into the main canyon, where limestone mountains rise on either side and desert shrubs are scattered across the valley floor in an array of muted yellows and oranges. The boys are nowhere to be found.

“They’re not at the pullout we said to meet at … ” Hensley says as she pulls a U-turn. “Maybe they hitched a ride.” She is calm, as always.

I felt doubtful they would show up before, and now I feel sure that they won’t. If I was a teenager, and I had already been on my own overnight adventure, I would probably be exhausted from staying up too late. I would head home, over the idea of mentoring young kids. Suddenly, two figures appear in the distance, backpacks jostling. Javier and Pedro are running alongside the road toward the boulders. Laughing and covered in sweat, they hop into the van. “The drive for adventure is in all of us,” Andrew Lenz, founder of Escalada Urbana, a similar project in Rio de Janeiro that teaches young people from the favelas how to climb, told me. Like Smith, Lenz was a climber who believed in the sport’s ability to change lives.

What skepticism I had of the boys’ motivation evaporates.

“They will play some games and study,” Hensley explains after we’ve parked, “and then we get to climb.” She selects three different bouldering stations—mostly because there are only three pads—one easy problem, one slightly more difficult, the third hard.

The sun is suffocating, and there is dust everywhere from dirt bikes, but the kids don’t notice. They wrestle each other in line to get a turn at the stations. The younger ones get scared but push on with encouragement from the older volunteers and climbers. Some kids are clearly strong, with more experience, and fly up the problems, displaying finger strength and knowledge of body positioning.

Veronica elbows through the crowd of boys to the pad below the first problem, a slab with a wide crack. Her tiny hands paw at the rock. She climbs past the first crux easily. Ten feet of air swims below the final, reachy move. She needs to trust her feet and lock off. Seeing the difficulty, Veronica starts to downclimb.

“¡Venga! ¡Si puedes!” (“Come on! You can do it!”) we shout to encourage her. She looks down at Everardo spotting her. From the top of the boulder where I’ve been taking pictures, I gesture dramatically at the hold she needs to aim for. She loads up, reaching, but comes up short, backing down to solid feet.

“¡Venga, Veronica! Si puedes!” She gets her right foot up, her eyes determined, and locks off with her left arm, steeling herself to make the move. “¡VENGAAA!” we yell. This time, Veronica hits the hold to cheers. She pulls herself over the top, her face brightening into a big, toothy smile.

Sasha Turrentine is a climber, writer, and photographer based in Brooklyn, New York.