Excerpt: Dammed If You Don't, the New Book by Chris Kalman

"None"

Chris Kalman—a longtime contributor to Climbing Magazine—recently launched a Kickstarter campaign for his new book, Dammed If You Don’t. According to Kalman, the book is about what prominent Grand Canyon conservationist Katie Lee called “the conservation Catch-22: saving a wilderness takes enough people to destroy it.” It’s a story about how if we’re not careful, we can fall into the trap of loving places to death, in spite of our best efforts at protecting them. The campaign has already reached its Kickstarter goal.

Climbing editor Matt Samet was an early reader or Dammed. Here’s what he had to say about the book:

With Dammed If You Don’t, Chris Kalman spins a gripping, captivating story that’s part mystery, part The Monkey Wrench Gang, and part Crime and Punishment. It’s both a searing indictment of man’s greed and capacity for heedless destruction, as well as a finely wrought deconstruction of what can happen when even the best intentions go awry. Set amidst the lush, fictional Lahuenco Valley of Chile, Kalman’s novel deftly weaves together the interlocking threads of climbing, science, the complicated relationships climbing partners share with each other and their spouses, and how we so often destroy what we love in the name of “progress.” Read this book, I implore you—you will not be able to put it down.

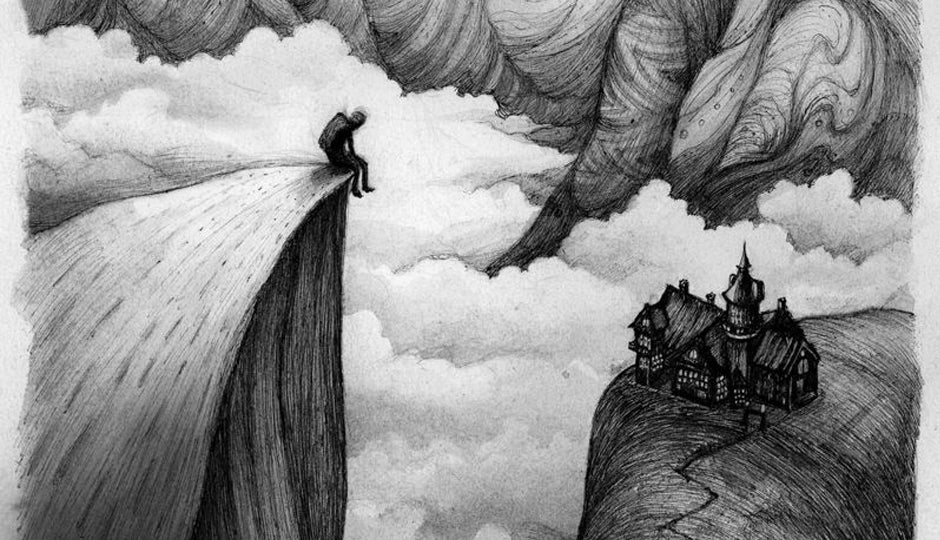

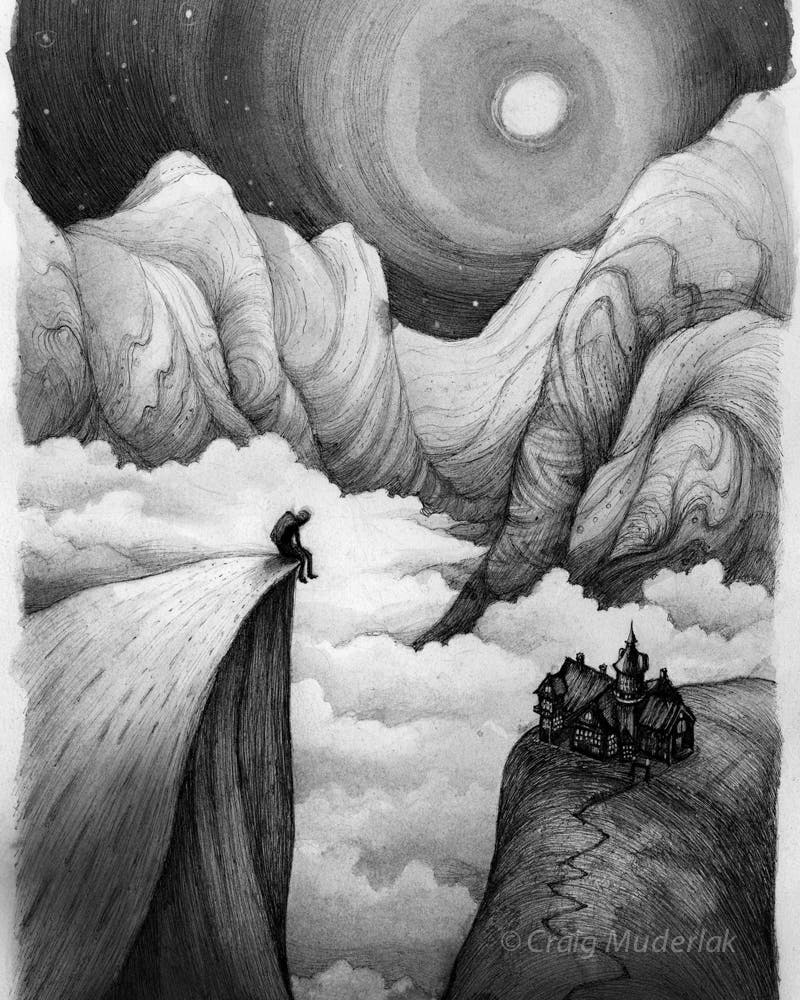

Dammed If You Don’t includes illustrations from Craig Muderlak, who also illustrated Kalman’s last book, As Above, So Below. Prints of Craig’s art are available from the Kickstarter campaign, as well as copies of the book.

Below is an excerpt from the first chapter of Dammed If You Don’t.

Excerpt

Nahuel woke to birdsong before the sunrise, a light mist blanketing the valley floor. He stood up sleepily, then nearly pissed himself when John clapped him on the back with a boisterous “buenos dias, amigo!” The gringos were already up, sorting climbing gear, food, machetes, and a first aid kit into piles on a blue tarp between the tents. Nahuel rubbed his eyes, muttering something under his breath about it being Christmas morning, hueyones culeados. Gary walked over, grunting salutations to Nahuel as he and John loaded packs.

“Quieren desayunarse?” Nahuel asked, hoping they might stay for breakfast. Gary held out what looked like a turd in a foil wrapper, laughing at Nahuel’s unveiled look of disgust at the energy bar. They shouldered their bags, grabbed machetes, and began walking matter of factly towards the river. Nahuel raised an eyebrow, and asked where they were going.

“Alla,” John said, pointing at the tallest cliff on the south side of the river.

“Conchetumare,” Nahuel whispered, looking up at the peak.

“We come back manana,” John said in his broken Spanish “o dia despues.”

“Bueno,” Nahuel replied, calculating how much money he could get for their gear up in the city if they did not return at all. “Que les vaya bien.”

John and Gary cut poles of caña colihue—an Austral relative of the bamboo family—and awkwardly staggered their way across the river. The water did not rise above their hips, but the current was strong and the bed was lined with slippery round stones which shifted under their bare feet. They waved to Nahuel after making it to the other side and lacing up shoes, then disappeared into the forest. They macheted their way straight up the steep mountain slope, climbing the springy branches of lenga trees where the terrain was near vertical. The steep climb gave way to a somber and quiet plateau where three-thousand year-old alerce trees stood as tall and stoic as redwoods. After three hours of hard and sweaty hiking, they were finally at the toe of the buttress. The wall seemed to curve like a scythe, or a crescent moon—slabby at first, then vertical, and finally overhung, the top guarded by roofs and hanging bottomless corners.

After walking along the base to find a suitable place to start climbing, John and Gary sat down and took a brief break. Out from the packs came the gear. They rock paper scissored to see who would go first. Gary won, so he tied in to the top side of the rope (John, the bottom) changed into climbing shoes, and clipped clinking aluminum chocks and spring loaded camming devices to his harness. He and John locked eyes and bumped fists, their spirits flying like school children at recess. Then Gary began to climb.

Gary moved up the wall like a tai chi master, or a ballerina—all controlled strength and elegant balance. He pressed the flat soles of his shoes onto the wall like a gecko, adhering through unseen forces. He did not pull his body up with his arms, but used his palms to shift his center of gravity left and right above his feet, allowing his leg muscles to generate the upward momentum. He was neither quick nor slow; his body neither rigid nor flaccid. As Gary climbed, John continually fed rope from the pile on the ground through his belay device, giving just enough slack not to restrict Gary’s movement, but not so much as to unnecessarily lengthen a potential fall. At one hundred feet, John called out “Half rope!” letting Gary know that in another hundred feet there would be no more slack. Gary climbed fifty feet further until he reached a flat ledge the size of a park bench. He stopped, built an anchor, clipped in, and yelled down “Off belay!”

They ascended the wall like a game of hopscotch. Gary would lead, pause to build an anchor, and John would follow. Then John would collect the protection, lead to a logical stopping point, build an anchor, and Gary would follow. They would not have seemed—had they been watched through a spotting scope as is done in the Alps—to move quickly. Nor did they tarry, except for sections where the crack was swallowed up by mud and vegetation, forcing them to pause at tenuous stances and scrape desperately with finger nails and wire brushes to excavate a spot to place protection. When these efforts were fruitless, they hammered pitons the width of butter knives into narrow seams. When placing pitons failed, they gathered courage and continued climbing unprotected, hoping to find better luck ahead. Both climbers were fortunate on multiple occasions to avoid potentially fatal falls. They climbed like this throughout the day, the meters and hours falling away behind them like water downstream.

Just below the summit, a final overhang jutted imposingly overhead like the prow of a ship. John attempted to traverse left, then right to circumvent the final obstacle, but was unsuccessful. As Gary belayed these efforts, he looked up at the seemingly impossible overhang. He started to perceive a constellation of possible hand and foot holds. He imagined his body performing an elaborate dance: left hand up to the inverted undercling, right hand far right to the vertical edge, left heel pressed on to the protruding knob, right toe pushing down on the horizontal edge, left hand up to the hand crack, spin the body 180 degrees and kick the feet upside down over the head catching the toes from the lip of the roof, place protection in the hand crack, right hand to the lip, then left hand, press down and roll over. He could feel his pectoral muscles flexing through the compression moves, the calf muscle burning from the heel hook, the vertiginous feeling of inverting with one thousand meters of air beneath him.

John made his way back to the anchor looking deflated and defeated, and talking about going down. But Gary interrupted him, and walked him through the sequence he had in mind.

“I told you we should have brought the bolts,” John said. If they had, they could have safely protected the moves.

“Fuck the bolts,” Gary said; “give me the rack.”

John shook his head, but did as he was told. Then he watched, dumbfounded and awestruck as Gary flawlessly climbed the moves exactly as he had described them—the veins bulging in his forearms, his breathing deep and intentional as he maintained composure through the dangerous inversion. He disappeared over the lip of the roof, then let out a victorious whoop which rang through the valley.

Gary pulled up the slack, then John tried the moves. He made it to the inversion by the skin of his teeth, but lacked the abdominal strength to kick his foot over the lip, falling on the taut rope and swinging into space. Jesus christ, he thought, grateful to be following instead of leading, and trying not to imagine what would have happened to Gary had he fallen. Unable to swing back into the wall, John was forced to tie two prusiks and ascend the rope to Gary instead.

Now safely on relatively flat ground, they untied, coiled the rope, slung it over a pack, and hiked the last hundred meters of nontechnical ridge to the summit. When they arrived the light was fading, and everything was cast in a sublime crepuscular stillness. The air chilled, the bellies of clouds shone with the final pink radiance of the day, the clicking of bats seeking insects filled the air. Gary was struck by the sensation of being seen by unseen creatures.

To the south, buttress after buttress extended into the distance like layers of an onion, cut in half and left peeling on the counter. North, on the other side of the Rio Lahuenco, alpine ridges emptied their snowfields into sapphire blue lakes. East, the deep emerald defile and the shimmering river went on as far as the eye could see. Down below was the peaceful meadow at the forest’s edge. They could just make out their tents—small dots of out-of-place fluorescent color. And to the west, a blood orange sun melted into the Coinco fjord. The village of Calihue was somewhere in the distance, along the two-track that wrapped out of sight to the north.

They settled in to sleep upon the summit, which was not—it turned out—a dramatic point at all, but a plateau as broad and flat as a granite football field. They spread out ropes as makeshift pads and spooned together under a single sleeping bag breathing small clouds into the quickening darkness. The gaseous glow of a thousand galaxies bombarded their tired minds, barring them from sleep. The Southern Cross, the luminous Milky Way, an endless stream of shooting stars. They spent hours in silent wonder at the world they inhabited, their place in it, the inconceivable fact that no other human had ever been there before. And finally they slept.