Jerry Gallwas Established the U.S.’s First Big Wall. It was the Defining Moment of a Brief Career.

The imposing Northwest Face of Half Dome, in Yosemite. (Photo: Ron Reznick/VW Pics/Getty)

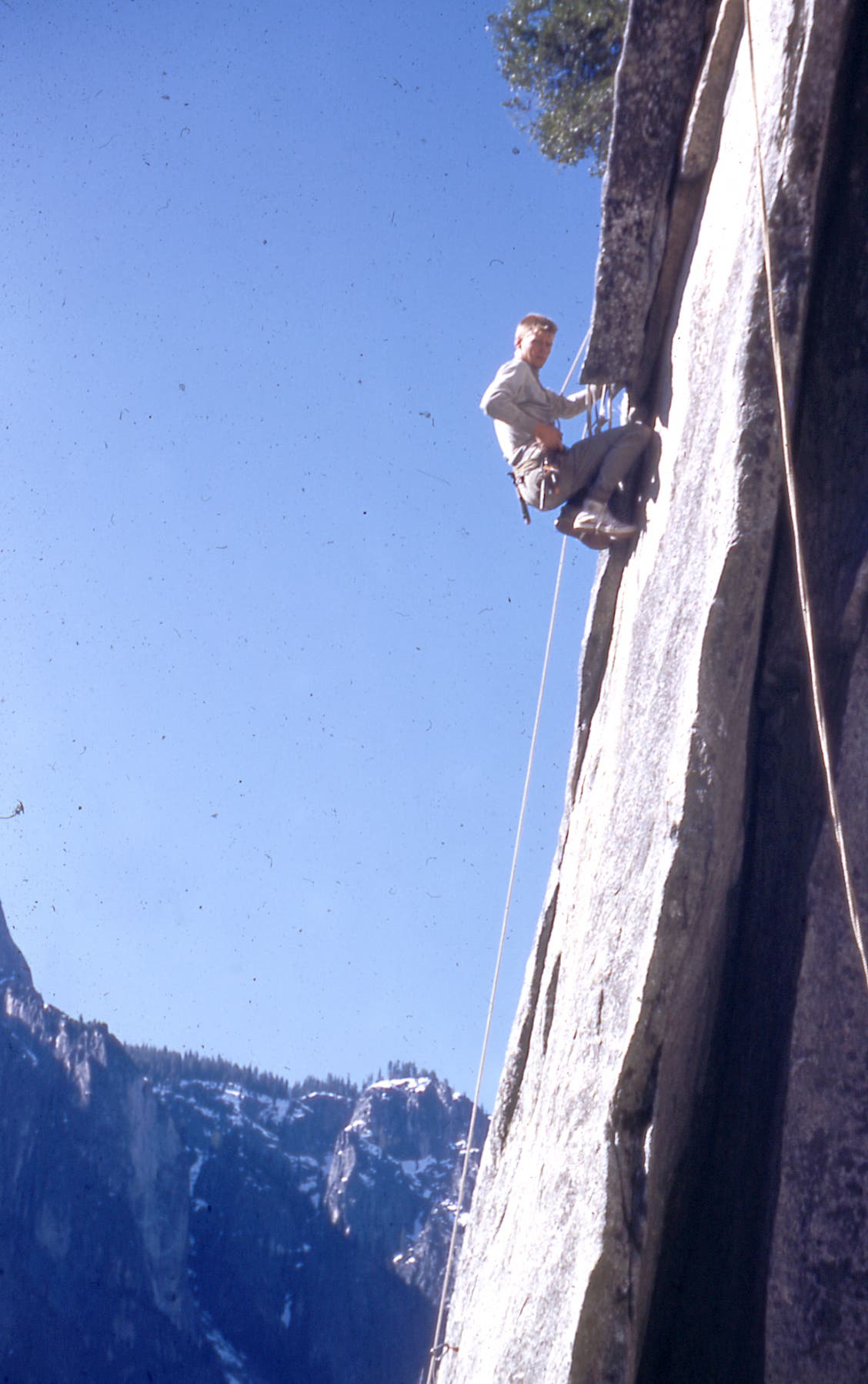

Big wall climbing was established in America in 1957 with the ascent Half Dome’s 2,200-foot Northwest Face. This pioneering route, the first grade VI in the country, paved the way for US climbers to leapfrog their European counterparts in both length and difficulty. And the techniques honed on the storied walls of Yosemite Valley led to groundbreaking ascents on the world’s great granitic ranges.

To be sure, routes in Yosemite such as the 1,200-foot Lost Arrow Chimney, the 1,700-foot Steck-Salathé, and the 1,800-foot North Buttress of Middle Cathedral Rock, done in the late 1940s and early ’50s were multi-day climbs, but none approached the level of difficulty and commitment of Half Dome. And just who was capable of such an undertaking?

Jerry Gallwas was 15 when he started climbing at Mission Gorge in 1951. The slick granite knolls were undoubtedly home to the most popular climbing area in the San Diego area, even if most of the routes were only 40-80 feet high. Gallwas, like all aspiring Southern California climbers of the era, dreamed of climbing the comparatively massive 800-foot Tahquitz Rock: the ultimate proving ground due to its size and difficulty of routes. It was there, in 1952, that he met two other up and comers, 17-year old Royal Robbins and 16-year old Don Wilson.

The lure of Yosemite’s legendary, towering walls was great and in 1953 Gallwas and Robbins climbed the long, adventurous Yosemite Point Buttress where they suffered through a cold and rainy bivouac high on the face. With important lessons learned from that epic, such as bivouacking on a ledge with wood but having no matches, they, along with Don Wilson, made the second ascent of the intimidating Steck-Salathé on Sentinel Rock where they cut the climbing time from five to two days.

After climbing several of Yosemite’s biggest test pieces, it was evident to Gallwas that the soft-iron pitons that most climbers were using just didn’t cut it on longer climbs. Repeated placement and removal quickly reduced their usefulness. “I had read Ax Nelson’s article in the Sierra Club Bulletin, “Five Days and Nights on the Lost Arrow,” and had seen the photos,” recalls Gallwas. “A fortuitous find of an anvil in the spring of 1953 inspired me to learn how to make pitons so I spent many weekends working with the forge, drill, and grinder.”

Gallwas convinced an engineer friend to let him access his commercial heat-treating facility and by the end of the month Gallwas had churned out “two or three dozen” 4130 alloy chromoly pitons, inspired by the legendary climber John Salathé’s designs.

Now with the proper tools, the next logical progression looked to be the vertiginous Northwest Face on Half Dome and in 1955 Robbins, Gallwas, and Wilson were joined by Sacramento climber Warren Harding for an attempt.

The length and difficulty of the Northwest Face of Half Dome was immediately apparent. A poor route-finding decision resulted in long direct-aid leads, and the team’s pace slowed to a crawl. After two days on the wall they had climbed only 450 feet. On the third day Harding was all for continuing to “slug it out” on the difficult terrain—he’d found great success with this dogged tactic, having just made the first ascent of the North Buttress of Middle Cathedral—but Wilson favored a more “fast and light” style. After a terse discussion they retreated.

“The mood of the four of us in the 1955 attempt was very toxic,” remembers Gallwas. “Warren and Don were never meant to be on the same rope, let alone the same climb. We could have continued for another two days but climbing was intended to be fun and fun was nowhere in sight.”

Gallwas and Robbins were keen for another attempt, but because of the issues between Don Wilson and Warren Harding in 1955, Warren was not invited on the climb. As it turned out, the spurned Harding was rumored to be planning his own attempt which accelerated the plans of Gallwas and Robbins. Unfortunately, Don Wilson could not get time off from work on such short notice.

Finding a last-minute partner in Yosemite was much harder in 1957 than it is today. There were no resident climbers in the Valley at that time; everyone had regular jobs and came into Yosemite on the weekends to pursue their craft. Robbins and Gallwas desperately wanted the first ascent of Half Dome’s Northwest Face but quivered at the thought of embarking on such a wall as a lean team of two. They recruited the young Mike Sherrick, a strong and stoked Southern Californian climber.

Harding was on a work trip to Alaska, but his return to the Valley was imminent. “For Royal and me, it was now or never because Mark [Powell] was at the top of his game and Warren was tenacious beyond any failure when he set his mind to it,” explains Gallwas. “We were going for the gold with apprehensions but no sense of failure.”

Trying to utilize the most climbable features their proposed route broke the face into three distinct sections: the initial 900 feet ascended straightforward, obvious crack features, as did the final 1,000 feet. It was the middle section, a 300-foot rising traverse to link the lower and upper sections which appeared blank and was most likely the crux of the route. This was the reason the team brought 1,200 feet of rope as well as much more gear than food or water.

“We were haunted by Toni Kurz’s death on the Eiger—not being able to retreat across the Hinterstoisser Traverse—and took extra rope to ensure our ability to get off the face,” recalls Gallwas. “That was a miscalculation because a rope is eight pounds, as is a gallon of water. Had I sat down and really planned, it would have been obvious to take more water, and less rope. I would certainly have taken my camera which I left behind with the idea of saving weight. Not so smart and certainly poor planning!”

Gallwas and Sherrick, both 21 at the time, and Robbins, 22, had planned for a five-day ascent. By the afternoon of day two, being more familiar with the route and much better prepared than two years before, they cruised through their high point from the 1955 reconnaissance and were forced to confront the dreaded traverse. Robbins and Gallwas used eight homemade pitons, seven expansion bolts, and a novel technique which came to be known as the “pendulum” to solve the blankest spot and reached the upper wall’s chimneys, flakes, and cracks early on the third day.

“Sleeping at the base of Psych Flake, someone dropped an aluminum film canister from the Visor and it ricocheted down the flakes creating a haunting sound as we knew how fragile the flake system was,” remembers Gallwas. On the fourth day, at the top of the flake system the Zig Zags were tough given their condition and they bivouacked at the top of the feature with Gallwas sitting on a nubbin of rock with Robbins and Sherrick several feet below.

The next morning, with luck on their side, they discovered a 50-foot ledge leading out left which bypassed the frightening overhangs of the Visor above. It was the exact weakness they needed. They were hopelessly committed, having just thrown most of their aid-climbing gear off the wall. “The name tells it all,” remembers Gallwas. “We were committed as we had dropped all our extra gear and committed to go for the summit. The Visor is very intimidating—so Thank God says it all!”

“It was exhilarating. It was the way out from under the Visor and the goal was in sight,” adds Gallwas. “I gulp every time I see the photo of Alex Honnold in a red shirt and no rope standing up. I put in a couple of big angle pitons and moved across with little remembrance of what techniques of style I used. I do remember wishing I had a camera as no one would see the ledge until later climbers came along.”

The trio climbed one final pitch of difficult aid climbing and soon were on the summit where they had a most unexpected welcoming party. “Warren was there to meet us with ham sandwiches, water, and a very welcome but salty greeting,” recalls Gallwas. The three had beaten Harding to the route but, in a classic case of one-upmanship, Harding would make the first ascent of El Cap via the Nose the following year.

Being weekend climbers, Gallwas, Robbins, and Sherrick had little time to celebrate their groundbreaking achievement. “We were all going to be late for work and didn’t even think to get a photo of the three of us when we got to the Valley, my camera was in the car,” remembers Gallwas.

Studying Chemistry at San Diego State, Gallwas’s life took an abrupt turn after his success on Half Dome. “The draft board made it clear that I was going into the Army as soon as I graduated. They recognized a career student, so I got to work with my final grades and draft notice coming in the same mail.” Gallwas’s army experience turned out to be great as he supervised the chemistry section of a 300-bed station hospital and in the process learned clinical chemistry. While he regrets the years lost to climbing he admits that “it was a hobby and not a career.”

After two years he mustered out and joined Beckman Instruments. His 30-year career included designing, building, and marketing clinical laboratory instruments. He went on to consult widely and serve on numerous corporate and nonprofit boards. “That was my professional life for nearly 30 years which could not have happened had I not had the Army hospital lab experience,” explains Gallwas.

His climbing career ended in 1966 on the slopes of Southern California’s iconic Mount Baldy. Caught in a blinding snowstorm he and his partner “slept or tried to” until dawn. “I made a classic mistake and didn’t throw a snowball into a steep couloir to check if the snow was hard or soft and before I knew it, was headed down a 500-foot chute,” remembers Gallwas. He hit a ledge, did a 360, and landed on his belly with his pack still on and his ice axe in hand, allowing him to self arrest before smashing into the rocks below.

“I was a hematoma from my navel to my ankles,” recalls Gallwas. “After telling me I was lucky to be alive, the surgeon removed two inches of duodenum leaving a belly scar just where in those days you would tie a rope.” It took two years before he could wear a belt and by that time Gallwas was engrossed in a small team developing a multi-million dollar business and raising two kids. He missed climbing but was just too deeply involved with family and work.

Looking back on his climbing career Gallwas is characteristically humble about his historic achievements which also included first ascents of the classic desert towers the Totem Pole, Spider Rock, and Cleopatra’s Needle. “I was a weekend climber and climbed as a passion,” he recalls. “I was a consistent climber but not a hot shot.”