Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

Free soloing means climbing with no rope or gear, a historic genre that in the late 1970s, through the Yosemite-based John Bachar—at the time nicknamed Mr. Norelco, after a “cordless” electric razor—entered mainstream American consciousness. In 2018 the genre exploded in the national and international consciousness with the release of the cinematic and deeply involving film “Free Solo.”

“Free Solo” chronicles Alex Honnold’s mission to achieve his historic free (and the first ever) solo of the iconic 3,300-foot El Capitan, in Yosemite Valley, California, completed June 3, 2017. Directed by Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi and Jimmy Chin, it won the 2018 Academy Award for Best Documentary. (See trailer here.)

The term free soloing is usually applied to steep and technical rock climbing done with only hands and feet, with the sole equipment being climbing shoes and chalk bag, but the word solo also applies to ice climbs and routes done ropeless in the Alps and Greater Ranges. Soloing can also mean going alone with a rope, but free soloing means no rope.

For the climbers below, free soloing is one aspect in a mosaic of climbing experiences and achievements. As one example, John Bachar and Peter Croft are known soloists but were also the first ever to climb (roped) both El Capitan and Half Dome in a day, in 1986, which each considered a great career high point.

Soloing is only done by a minority; most climbers do not practice this extremely dangerous genre. In some ways it was more common, though less known, in the past, when some trad climbers might move unroped on easy ground at the bottom or top of a route; some still do. A fair amount of experienced climbers have done a small amount of soloing, for its simplicity and convenience (such as when no partner was available), and stopped. The text below contains this typical post from an online discussion: “I have in the past but not anymore.”

This compendium aims to be comprehensive, but please understand it cannot cover everything. The intent is to show many major events in the greater context.

This article is not an endorsement of the practice.

Please note that a number of links below lead to paywalled sources.

Leading American soloists

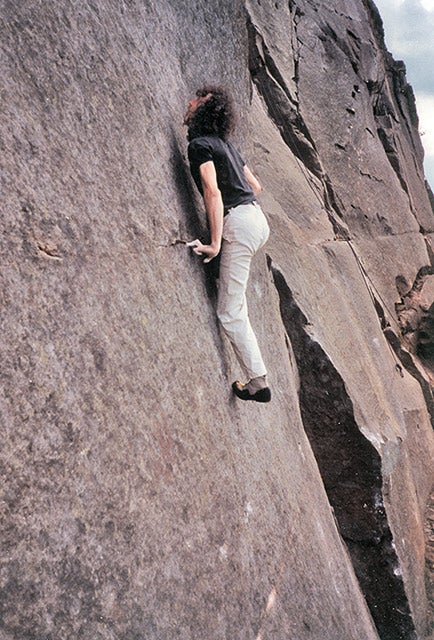

Even before John Bachar made shock waves by free soloing the three routes comprising the 450-foot Nabisco Wall (5.11), in Yosemite in 1979, came an equally stunning one for its era, by Henry Barber of New Hampshire. (See the end of this article for a passage about Royal Robbins’s soloes and extended quotes on his philosophy.)

In 1973, visiting Yosemite, the 19-year-old Barber pulled a visionary on-sight (first time on it) solo of the 1500-foot Steck-Salathé (IV 5.9) on Sentinel Rock, in 2.5 hours. In 1976, Barber at 22 soloed The Strand, a sustained E2 5b (5.10) with the hardest moves on top, at Gogarth, Anglesey Island, North Wales, for an “American Sportsman” television show. Before climbing that, he warmed up by soloing the nearby route Central Park, where a seagull swooped down and took his hat off.

“My solo career doesn’t remotely figure in today’s world,” Barber says today.

Still, he soloed hundreds of routes, on Devils Tower, Wyoming; in the Shawangunks, New York; in Arapiles, Australia; Dresden, East Germany, and a first ascent on Free Korea Peak in Kyrgyzstan. “When I went through all my records it turns out [my soloing] was 87 percent on-sight,” he says.

In 1972 Jim Erickson, who is responsible for about 100 first ascents in Eldorado, onsight free soloed the first ascent of the two-pitch Blind Faith (5.10a) on the West Face of the Bastille, Eldorado Canyon. Erickson did many such first ascents and is known for not having talked about them. He is also one of not many (see more below) to fall solo and survive, 35 feet, breaking both legs and incurring other injuries. He returned to climbing. Erickson was also on the FA of the world-famous 5.11 the Naked Edge.

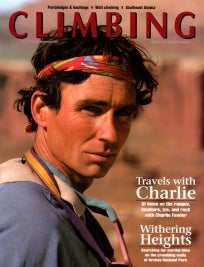

In 1977, Charlie Fowler free soloed the 19-pitch Direct North Buttress (5.10) of Middle Cathedral, Yosemite, an act called “probably the boldest solo of the 1970s” in Yosemite Climbs by George Meyers and Don Reid. In 1978, Fowler made the first solo ascent of the remote and forbidding Diamond Face of Longs Peak, via the Casual Route (5.10a), and he soloed the 1,500-foot The Flakes in the Black Canyon of the Gunnison, and also the three-pitch Diving Board (5.11a) in Eldorado Canyon, all Colorado; his solo of the Eiger is cited below. An exceedingly prolific climber, Fowler disappeared with his partner, Christine Boskoff, on Ge’nyen Mountain in China in late 2006. Their bodies were later found and identified. See this tribute.

In 1979 Earl Wiggins, 22, of Colorado Springs, free soloed the Scenic Cruise (V 5.10+), 13 pitches, techy and pumpy, and with an airy and insecure “Pegmatite Traverse” on slopers. He had in 1975 soloed (eking by, not in control) the two-pitch Outer Limits (5.10) in Yosemite at age 17, the day after falling 30 feet off it. On the Scenic Cruise he seems to have felt solid. His good friend Stewart Green says, “He told me that it went well with no problems. He was understated about the whole deal and modest.”

Jeff Achey in the book Climb! The History of Rock Climbing in Colorado, would write of the Scenic Cruise, “This ascent was the longest, hardest, and boldest free solo then done anywhere in the world.”

Wiggins was a creative, driven character, an in-demand Hollywood rigger, working on major films, as well as a top free climber who even in the early 1980s was not well known to climbers outside of his hardcore crew. Long troubled, a victim of mental illness, he took his life in 2002. See this profile.

In 1979, in what has been called on squamish.com “an astonishing landmark,” Greg Cameron free soloed the first free ascent of the now classic 450-foot Pipeline (5.10d), an offwidth at Squamish, B.C.

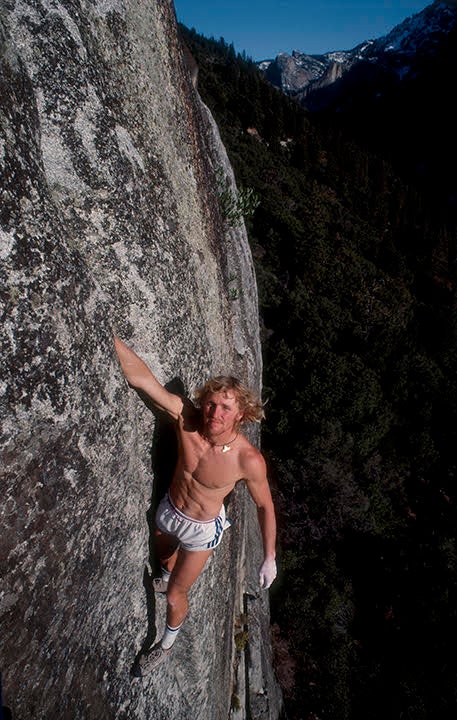

Bachar was a great soloing luminary, known for a brash though half-joking note on the bulletin board at Camp 4, the legendary climbers’ campground, in 1981: “$10,000 reward for anyone who can follow me for one full day.” He was profiled in a Rolling Stone article by Trip Gabriel called “Valley Boys,” and images of him soloing appeared widely elsewhere—in Life, Newsweek, and even airline magazines—in the lay media in ways previously unheard-of for climbers. Bachar also appeared in a television ad for Gillette razors. Among his multitudes of soloes were a smooth one of Leave It to Beaver (5.12b) in Joshua Tree, California, filmed by the television show “That’s Incredible!!” (see the video here), the Yosemite routes Crack A Go Go (5.11c) and The Moratorium (three-pitch 5.11, onsight), and The Gift (5.12c) at Red Rocks, Nevada, for Eric Perlman’s Masters of Stone video series. In 2005 he appeared in the documentary Bachar: One Man, One Myth, One Legend, written and directed by his friend Michael Reardon, also a prolific soloist, with whom he often spent long days soloing up and down multiple routes on Southern California crags such as Tahquitz in Idyllwild. (See Reardon below, and see an interview with Bachar by Eric Perlman here.)

He told Mark Kroese for the book Fifty Favorite Climbs: The Ultimate North American Tick List, of the Nabisco Wall:

“I knew I would blow everyone’s buzz. I got there and meditated for 10 minutes and just tried to zone out. Then I threw my shirt off and just fuckin’ went for it .… On Butterballs you’re in a sea of blank, vertical granite and there is this perfect finger crack. It’s like you’re on the side of a building, perfectly vertical and perfectly flat … and then you’re cruising on perfect hand jams and this absolutely bitchin’ wall and you’re feeling like the king of the world.”

Bachar died at age 52, out alone for what must have seemed a recreational solo on the local Dike Wall, Mammoth Lakes, in California near his home.

See this archival video.

Others of Bachar’s contemporaries who soloed included John Long; their friend John Yablonski, who like Bachar soloed Leave It to Beaver (only scraping by), and was a creative thinker in developing hard bouldering; and Ron Kauk of Yosemite. Kauk, one of the great talents of his generation, soloed the 18-pitch North Buttress (5.10a with a slick crux over 2,000 feet up) of Middle Cathedral.

Yablonski made the first lead, in a manner of speaking, since it was solo, of the previously toproped Joshua Tree classic Spiderline (5.11d). He was lucky as a soloist, once falling off a route only to land in a tree unhurt. A troubled soul, he died by suicide in 1991. See this account of his contributions to bouldering.

John Long, celebrated climbing author, wrote one of his most classic tales, “The Only Blasphemy,” as featured in the compendium Gorilla Monsoon and elsewhere, about trying to accompany Bachar on a “Half Dome day” of 2000 feet, 20 pitches, of solo climbing in the late 1970s. As Long describes it, he froze on the crux of their finale, a 5.11: “Then, as I splay my left foot up onto that slanting rugosity, the chilling realization comes that, in my haste, I’ve bungled the sequence …. A montage of black images floods my brain.”

Stuck, he realizes: “Shamefully, I understand the only blasphemy—to willfully jeopardize my life, which I have done, and it sickens me.” He squeaks through, and the next day does not climb but wanders the desert picking wildflowers.

Long also soloed the 1500-foot East Buttress (5.10b), on the far right reaches of El Capitan, in the mid-’70s.

In 1985 and 1987 Peter Croft was first ever to solo the famed and sustained Yosemite multi-pitch 5.11 routes The Rostrum and Astroman, and later in 1987 created a huge stir by soloing the two testpieces in a day. Also among his prolific solos are Blues Riff, a striking 5.11 crack in Tuolumne, and he had in 1984 soloed ROTC, an overhanging 5.11c, at Midnight Rock high on the rim of the river valley around Leavenworth, Washington. Croft, who would often decline when asked to be photographed soloing, is a venerable presence in the film Free Solo, and tells Honnold, who greatly respects him, that he doesn’t have to go through with the intent.

In 2015 Croft told Chris Kalous of the Enormocast podcast that he found soloing “too personal” to share, cautioning against the presence of a camera.

Today he says, “I do still solo but I rope climb more often. I’ve always been pretty spontaneous in my climbing and soloing does allow that better than anything else.”

Scott Franklin, probably the leading American climber at the time, established Survival of the Fittest (5.13a) in the Shawangunks, New York, in 1985, and soloed it in 1986, the first American to solo the grade, though he says he had done the route so many times (and its difficulties occur down low) that the solo was not major. Similarly, Russ Clune soloed Supercrack (5.12d), a climb he knew well, in 1985, feeling very solid. Yet it is part of the lore that the next time he got on it, taking a toprope from friends, he fell—and everybody screamed. His friend Jeff Gruenberg soloed Foops (stiff 5.11 roof) that year as well. Clune says that while they soloed that season, “That didn’t go on forever.”

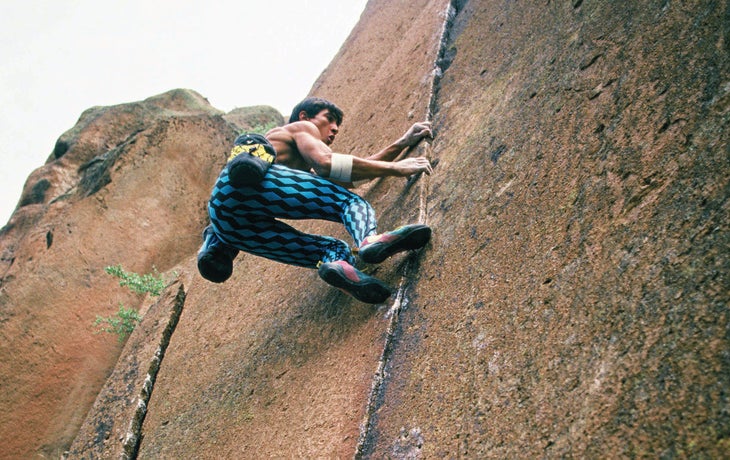

John Duran, a teacher and Native American climber now living in the Beijing region, was a legendary Southwest climber in the 1980s. Among his free-solos are Fainting Imam (then graded trad 5.13a; later 5.12c/d), Dreamscape (5.12a), and La Espina (5.12a), Cochiti Mesa, New Mexico, in 1988. He said in this interview: “I had a real purist’s attitude. That mentality of if you’re going to be out here soloing, you have to be on your business. I learned to block out the fear: OK, you have to perform and get in that place, be in the zone, not worried, confident, you know where the crux is. You kind of break it down mentally. I was Catholic, and I would pray an hour with a rosary before my hardest climbs.”

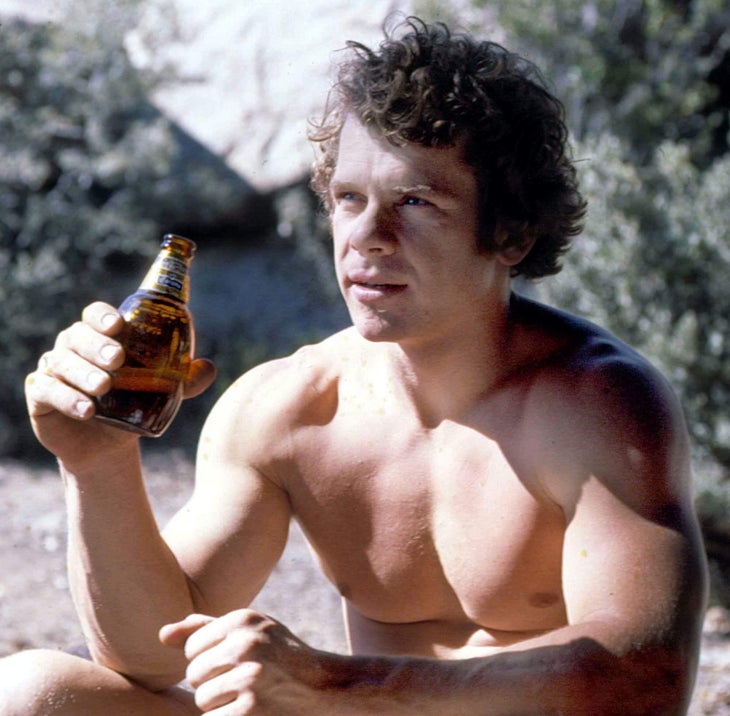

In the late 1980s and early 90s, a character from Manchester, England, found his “Office” in Eldorado Canyon, near Boulder. Derek Hersey was a cheerful and animated persona who soloed in the canyon regularly, known for appearing around a rock corner shouting, “Hey, punter!”

Hersey was the second person, after Jim Collins (in 1978), ever to solo the famous 460-foot Naked Edge (5.11), but is probably best known for three routes in a day (downclimbing one) on the Diamond. In 1989 he free soloed the 1000-foot Yellow Wall (V 5.11a), down climbed the Casual Route (5.10-), and soloed Pervertical Sanctuary (IV, 5.10), finishing before noon. In 1991 he free soloed Pervertical again and downclimbed the Red Wall (IV 5.10-). He was first ever to solo Pervertical.

He died in 1993 at 39 soloing the Steck Salathé, the day after climbing the Nose in a Day on El Cap (with a rope and partner). As is common in such cases, no one knows what happened: rain, a broken hold, a slip.

An obituary in the London Independent read, “In some ways it was fitting that the route was a 5.9 rather than, say, a 5.12, as there was no doubt that it was within his ability. Nor was there any question that he was doing it out of pressure or for accolades—out of anything but love of the experience.”

Roger Briggs, whose plan with Hersey had been to climb a new hard free (roped, not solo) route on the Diamond Face of Longs Peak, did the route with others and as a memorial named it The Joker (5.12c).

See Hersey in this video.

As of the late 1980s, Dan Osman of Lake Tahoe developed Cave Rock sport climbing, appeared at different times soloing in the Masters of Stone video series, and developed speed soloing in a dynamic style (which did not take) as widely shown on video on a Tahoe 5.7. Among Osman’s soloes were Gun Club (5.12c) in the New River Gorge, West Virginia, in 1990; Fire in the Hole (5.12b) at Cave Rock, and Atlantis (5.11+) on The Sorcerer in the Needles of California.

He established sport (roped) routes as hard as his well-known Slayer (5.13d), essentially developing the sport climbing in Cave Rock, Lake Tahoe. For a time it was a worldwide draw, though the climbing there was later closed.

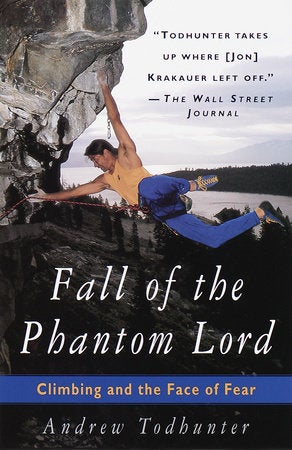

Osman also practiced roped bridge and cliff jumping. He died at 35 in 1998 when his rope broke in a jump from the Leaning Tower, Yosemite.

See the biography Fall of the Phantom Lord here.

In 2006, in El Potrero Chico, Mexico, Jimmy Ray Forester, a leader in the hardcore Texas and Oklahoma communities, failed to come home from soloing The Scariest Ride in the Park, a 40-pitch 5.9 ridge line. A search discovered his body on the ground the next day. Forester was active in stewardship and documentation. He died at age 43.

Duane Raleigh, then of Rock and Ice magazine, wrote: “Forester, a strong, talented and seasoned climber with 17 years experience under his belt, was an iconic figure throughout Oklahoma and Texas, where he repeated the classic runout trad routes and established a slew of his own in characteristically ground-up, onsight style, which he loved.” Imbued with a strong sense of climbing history, Forester was at the time of his death assembling hundreds of pages of route and historical info for a series of guide and history books to publish as a free resource. See this report.

Michael Reardon, close friend and a climbing (soloing) partner of John Bachar, was a film producer and former player in a heavy-metal band who came into climbing and became a self-designated professional solo climber. Another animated character, he was visible in the industry and palling around with Bachar at tradeshow events, and on the rock he soloed hundreds of pitches on these shores and in Ireland, where he had family and emotional roots.

In the video below, he describes his approach and operating mode—he projected an egg-shaped area of concentration, with his focus just above and below him, and slightly out to the sides. Reardon’s list of solos included the Palisade Traverse (VI 5.9) in 22 hours in the Sierra; an onsight solo of the Needles’ Romantic Warrior (V 5.12b) in 2005 and onsight-solo FA of the Shikata Ga Nai (5.12, 800 feet) in 2006, both in the Needles; Equinox (5.12c/d) and EBGBs (thin 5.10d) in Joshua Tree, California; and Ghetto Blaster (5.13a/b) in Malibu.

Reardon died July 13, 2007, on the coast of Ireland. Damon Corso, a photographer who had been shooting him from across an inlet, reported that after a day climbing up and down two routes on the 600-foot Fogher Cliffs, Valentia Island, County Kerry, Reardon was on a ledge above sea level, preparing to leave, when hit by a wave and washed out several hundred feet. Corso wrote on climbing.com, “The current pulled Mike out 150-plus meters in mere seconds. I ran up the hill to the Valentia Coast Guard station a mile away. Mike was still conscious in the water when I left him.” The Coast Guard arrived within 15 minutes, he said, but Reardon had disappeared. The Atlantic Ocean off Ireland in July is designated “cold swimming,” with temperatures of 57 to 61. Reardon was age 36.

See this video.

And read this remembrance by Bachar.

In April of 2000 Dean Potter achieved the second free solo, after Croft, of Astroman, as described by Steve Schneider in a summary of the season in the American Alpine Journal: “The other big news was Dean Potter’s free solo of Astroman. He is only the second person to make this climb in this manner, the first being Peter Croft. Although Dean used an easier variation to get around the technical crux of the third pitch, he deserves full credit for having mastered this climb.”

Potter also soloed Blind Faith (5.11) an equally hard or slightly harder variation to the Regular North Face on the Rostrum.

In 2002 the deeply spiritual Potter soloed Fitz Roy via the Supercanaleta (1,600 meters 5.10) and the Compressor Route (900 meters 5.10 A2) on Cerro Torre, and made a free solo—no rope or any gear—of a new 7000-foot variation he called Californian Roulette, on Fitz Roy. See this account.

In 2006 he did the first free solo of Heaven (5.12d) on Glacier Point, Yosemite.

In 2008 he achieved the innovative first “FreeBASE” ascent of Deep Blue Sea (5.12+) on the north face of the Eiger, in Switzerland, wearing a BASE parachute but no rope. See this 2014 interview, where he said, “Because I’m a free soloist, I think about odds. It’s not good enough to think: I will survive this once. When I think about doing something, I think: Will I survive a million out of a million times?”

Potter and his friend Graham Hunt died in a wingsuit flight in Yosemite in 2015.

In 2007, Steph Davis of Moab, Utah, became the first woman to solo the Diamond Face of Longs Peak, Rocky Mountain National Park. She first soloed the Casual Route (IV 5.10-) that summer, and on September 3, did the same on Pervertical Sanctuary (IV 5.1o). Overall she has free soloed the Diamond four times, twice via the Casual Route and twice via Pervertical.

Davis started free soloing at Lumpy Ridge in the early 1990s and continued over the decades in Yosemite, Tuolumne, Eldorado, Rocky Mountain National Park, and the Utah desert. Other free soloes include Incredible Hand Crack (5.10), Coyne Crack (5.11d) and Scarface (5.11) in Indian Creek, in around 2000, and Outer Limits in Yosemite circa 2002.

In 2008, Davis free soloed the North Face (5.11a) of the nearly 400-foot Castleton Tower, Castle Valley, Utah, and BASE jumped from the top.

See her website, which describes her memoirs, here.

Brette Harrington, from Lake Tahoe but at length based in Squamish, B.C., in 2015 free-soloed Chiaro de Luna (5.11a), Saint Exupery, Patagonia. She has climbed many rock routes solo at Squamish. Harrington is a top all-around climber with leading ascents from sport routes to multipitch trad first ascents to significant firsts on alpine terrain, culminating in the FA of the East Face of Alberta’s Mt. Fay, Alberta. Harrington was the partner of Marc-André Leclerc, legendary alpinist (see entry on Leclerc below) and is a major presence in the current film The Alpinist. See this interview with her.

Most people know Brad Gobright, a Boulder climber originally from Orange County, as the charming, donut-eating subject of Cedar Wright’s 2017 half-hour documentary “Safety Third,” in which Gobright makes the first solo ascent of Hairstyles and Attitudes (5.12c), Eldorado Canyon. There is actually an alarming instant during that ascent, while what is more impressive is Gobright’s easy-breezy climbing and soloing all over the canyon, route after route. The film was part of the traveling filmfest Reel Rock in its 12th year.

He and Jim Reynolds were also standout, hilarious presences in Reel Rock 14 in 2019, with the hour-long film The Nose Speed Record. The film shows how Gobright and Reynolds, by their own account humble dirtbags, take the speed record on the Nose of El Capitan, with 2 hours, 19 minutes. Alex Honnold, previous record holder, calls to congratulate Gobright, and arrives with Tommy Caldwell to take it back (in 1:58).

Gobright was fast and prolific on El Cap, with one major accomplishment being the first free ascent (FFA) of the Heart Route (VI 5.13b), with Mason Earle, in 2015.

In late 2019 Gobright, 31, died in a rappelling accident in El Potrero Chico, Mexico.

In spring of that year, 2019, Jim Reynolds free soloed Afanassieff (5.10c), up the 5,000-foot tower of Fitz Roy, Patagonia. He then free soloed down the route in the dark, on rock wet with ice melt, a near inconceivable 10,000 in total feet. See this account.

Austin Howell, well-known through an Instagram account called “Freesoloist,” climbed ropeless very regularly, including doing 19 5.12s (up to 5.12c). He once gave the community a huge congregate chuckle by soloing a Linville Gorge 5.9 wearing only a hat.

Howell, 31, wrote openly about soloing having helped him in dealing with depression and other mental-health disorders, posting: “Freesoloing isn’t a death wish, it’s a life wish. It’s the single best therapy I’ve ever found for calming my tumultuous mind. The control that I’ve developed on the wall transfers into my daily life.”

He was killed in a fall at Shortoff Mountain, Linville Gorge, North Carolina, in summer of 2019.

See this news account and this obituary.

Clark Jacobs of Idyllwild, California, was believed to have soloed the local 5.9+ Flower of High Rank as many as 500 times. He died in 2021 of natural causes at age 67. See this obituary.

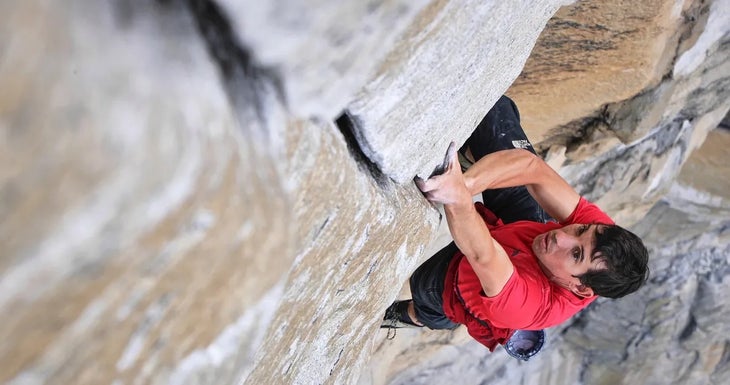

Alex Honnold, of course: As of 2017 Honnold became first to free solo El Cap proper, the big wall section, via Free Rider, 30 pitches, 5.12d. See the Academy-Award-winning film “Free Solo,” streaming still.

In 2007, Honnold became the third person, after Croft and Potter, to solo Astroman, where he took the harder variations, and the Rostrum in Yosemite; and he soloed the exposed Heaven (5.12d).

In 2008, Honnold free-soloed the nine-pitch Moonlight Buttress (5.12c) in Zion, Utah, called by Mountain Project “perhaps the most spectacular, and arguably longest and hardest, sandstone climb in the world.”

Also in 2008, he free soloed the Regular Northwest Face (5.12) on Half Dome, Yosemite, for the first but not last time.

In 2012 Honnold soloed The Triple, enchaining Yosemite’s three biggest faces—El Cap, Half Dome, and Mount Watkins, free soloing all but 500 feet of the 7,000 feet of climbing in under a day. Earlier that season he had been the first to free solo the 1500-foot West Face (5.11c) of El Cap, and he and Tommy Caldwell free climbed the entire Triple on terrain of up to 5.12+. The Triple was first enchained by Timmy O’Neill and Dean Potter, using free and aid methods, in a day in 2001.

Honnold wrote: “Overall, freeing it was physically harder, since we had to climb 5.12 pitches after already doing two walls. But soloing it felt a lot more intense, probably because I was just a little on edge the whole time.”

In 2014, he climbed the 15-pitch El Sendero Luminoso (5.12d) in El Potrero Chico, Mexico. The route is not only hard and sustained but features balance-y, insecure moves (that he had analyzed and practiced assiduously).

Also in 2014 he soloed the 12-pitch University Wall, Squamish Chief, British Columbia.

In 2021, in “The Longest Solo of All Time,” Vitaliy Musoyenko linked 80,000 feet of the Sierra Crest, California, climbing approximately 10,000 feet a day up to 5.9. See his feature account here, containing historic information on other long Sierra traverses. Several experienced climbers have had accidents on these mountain traverses. In 2012 Michael Ybarra, 45, who wrote about climbing and other outdoor sports in the Wall Street Journal and elsewhere, died in a fall on the Sawtooth Ridge Traverse, the Eastern Sierra, which he undertook solo. See the entry on him in Climbers We Lost 2012. In 2016, Julia Mackenzie, 30, fell on the Evolution Traverse, when she broke a hold while climbing with a partner but unroped. See entry on her here.

Accidents

Aside from the tragedies above (and others listed below), various climbers have had soloing accidents. See this article with accounts of falls by Bachar, Reardon, Ben Heason, James Lucas, and Doug Heinrich, all of whom survived, though the first two have since passed. Some other incidents are these (this is not a comprehensive list):

The 29-year-old Elizabeth “Lyzz” Byrnes of Moab, Utah, a dedicated year-round climber there, fell from 60 feet up, just shy of the anchor, on a 5.10 in Indian Creek in 2001.

This discussion upon news of her death was respectful and representative in terms of climbers understanding the purity of the experience, while expressing sorrow and cautioning others about soloing, with this as a typical sentiment: “I have in the past but not anymore.” Another poster reminded those in the discussion never to be pressured into it.

In 2008, George Gardner, age 58 and a greatly experienced, revered Exum guide in the Tetons, took a fatal fall on what would have been for him a routine evening solo on the Grand Teton. He was thought to be on the Lower Exum Ridge. See this report.

In December 2018 Timothy Wibisono, 41, of Baltimore fell to his death soloing at the Trapps.

In 2019, the genial Bob Dergay, 48, an all-arounder who climbed rock, ice, desert and mountain routes, died soloing the classic (and to him familiar) Bastille Crack in Eldorado Canyon. See this obituary.

In 2020, Mike Flood, age 58, another seasoned climber who would have thought he was doing nothing unusual, fell 50 feet soloing the 5.9 Potholes at Stoney Point, California. Flood, who worked in machine maintenance and was considered to be a serious and analytical climber, survived, with life-changing injuries. See this news account.

In 2021, Josh Ourada, age 31, fell soloing the multipitch Nutcracker (5.9), Manure Pile, Yosemite. He fell over 150 feet, from the fourth pitch, and landed on a ledge, where another climber jumped out of the way, and then helped him. Ourada survived and expressed his regret. See this news account.

Also in 2021, Scott Dewey, 31, an all-around outdoorsperson, guitarist and student who was said to like to solo a number of pitches in the morning before class, died in Eldorado Canyon, Colorado. See this obituary.

In January of 2022, Michael Spitz, 35 and a teacher, was found at the base of Illusion Dweller (5.10+), one of his favorite climbs in Joshua Tree, California, and one he had soloed before. Spitz soloed often but mostly did not talk about it. See this account.

International

The following are a few international examples.

In 1985 a 20-year-old Antoine Le Menestrel (France) stunned the climbing world by soloing Revelations, Raven Tor, one of Britain’s hardest climbs. In this journal account, he wrote: “I am at the foot of the route, my head is empty, my body filled with concentration. … The moves are linked in perfection; no hesitation, no unnecessary movement, no tension, just total concentration all the way to the top. I climbed into a state of grace as I had never before climbed.”

In 1986 Ron Fawcett (UK) soloed 100 Extremes (5.10 verging into 5.11) on gritstone, starting at Froggatt Edge and finishing at Curbar, both near Sheffield, England. His 100 routes, as he wrote in his book Ron Fawcett: Rock Athlete, totaled 3957 feet of climbing, with 12 miles of hiking and running from crag to crag. “My brain ached with the tension of so much soloing,” he wrote of approaching the last routes. He climbed morning to dusk, seeing few people and finishing alone, “at peace.”

In 2014, James McHaffie (also UK) was partially inspired by the above to solo 100 Lakeland Extreme routes.

Another British climber, the congenial Philip “Jimmy” Jewell, was renowned for soloing multitudes of pitches. He was known for saying once: “I can’t pull on the smallest of holds, but those I can pull on, I can pull on all day.”

Paul Williams photographed Jewell soloing The Axe (E4 6a) at Clogwyn Du’r Arddu, North Wales in an image that became the cover of the 1989 Clogwyn Du’r Arddu Guidebook.

See this video. One of the narrators describes the film, meaning soloing, as “about total self-reliance.”

Jewell, 34, died in autumn of 1987 on a very moderate climb, Poor Man’s Peuterey (Severe, ie about 5.6) at Tremadoc, North Wales, soloing it in his “trainers,” or trail shoes. The three-pitch route has slick slab and groove moves that are often damp.

In another sad irony, in 1995 the also affable Paul Williams, guidebook author and pillar of the British scene, died one evening soloing Brown’s Eliminate (5.10d), a route he often used as a warmup. He was 49.

Nick Yardley (UK-USA) calls the route “a classic moderate solo for us all at the time.”

“As he went up the face, apparently an edge snapped,” Yardley says. “He fell to the ground and landed hard, no mats then. At first he just sat there joking, saying he was good, but he had massive internal bleeding and soon passed out and died—a true character with a genuine heart. To us younger climbers, he was very much an encouraging father figure, pointing us at routes, pushing us, but also buying beers and giving rides.”

Catherine Destivelle (France) free soloed El Matador (5.10d) on Devils Tower in 1987, for a dramatic reel where she starts out using cams and a self belay (see it here) and soloed the Old Man of Hoy, a sea stack off the coast of Scotland, in 1998. Destivelle was the first woman to solo the North Face of the Eiger, in 1992, onsight; she also soloed the north face of the Grandes Jorasses in 1993 and the north face of the Matterhorn in 1994. See this account.

She said in a 2020 interview: “When I’m free soloing, I feel O.K. I always have a big safety margin, I’m not struggling. You feel quite powerful and calm. If I ever felt afraid, I wouldn’t go. I don’t like to bet. That goes for everything. I don’t run after luck. With my publishing company, it’s exactly the same. I go step by step and build something.”

Patrick Edlinger (France) appeared at age 23 soloing in the 1500-foot Verdon Gorge in the 1983 film Life by the Fingertips. Like Destivelle above, he was a World Cup comp climbing winner. See video here.

Edlinger died at 52 in a fall on the stone stairway of his home. See “The Triumphs and Tragedy of Patrick Edlinger.”

Alain Robert is another French climber known for soloing in the Verdon, as featured in the 1991 documentary Alain Robert en solo integral. Among his soloes is also La Nuit du Lézard (5.13c) in Buoux in 1991. He is known as well for climbing buildings (see below, linking to a New Yorker profile).

Wolfgang Güllich (Germany), author of the world’s first 5.14d and many other milestone climbs, was first to free solo the massive roof climb Separate Reality (5.12), 600 feet above the valley floor, Yosemite, in 1986. A little-known fact is that the photographer Heinz Zak repeated the solo; so did Dean Potter and Alex Honnold.

Güllich died in a car accident in 1992.

Alexander Huber (Germany) soloed the 70-foot Kommunist (5.14a) at Schleierwasserfall in Austria in 2004; also The Opportunist (5.13d), at Schleier, in 2003.

Hansjorg Auer (Austria) soloed the 37-pitch Via Attraverso il Pesce (The Fish Route: 7b+/5.12c, 37 pitches, 850m), in 2007. The year before he soloed the 27-pitch Tempi Moderni (Modern Times: 5.11c), also in the Dolomites. He died in 2019 in an avalanche on Howse Peak in the Canadian Rockies with David Lama (Austria-Nepal) and Jess Roskelley (USA).

Ice, alpine

Some of the ice and alpine climbers known for hard ropeless climbing:

In 1971, John Bouchard forged up the 600-foot Black Dike, Cannon Cliff, New Hampshire, a cold, dank cleft that Yvon Chouinard had called “the last great problem” of Northeastern ice climbing. Bouchard, age 19, had intended to come with a partner, who bailed; had intended to rope solo it, but the rope stuck and he had to leave it; dropped mittens and broke a pick. But he survived (horrified), and the tale became both a turning point for the region and a legend. See this account.

Jeff Lowe soloed Bridal Veil Falls in Telluride in 1978, and in 1979, the South Face of Ama Dablam. He later self belayed on his 1991 route Metanoia on the Eiger. Lowe died of natural causes in 2018.

Tobin Sorenson was a brilliant climber with leading ascents in Southern California, Yosemite, the Canadian Rockies, the Alps, and Australia. In 1980 Sorenson died at 25 soloing the north face of Mount Alberta, Canadian Rockies.

John Mallon Waterman of Fairbanks was an early and bright talent who gained international experience and amassed many mountaineering achievements but was a complicated person who climbed solo increasingly often. His signature route is the Southeast Spur of Hunter, on which he spent 145 days alone. “The Hunter climb defies being put in perspective. It was a new route, a first solo ascent of the peak … a very serious undertaking,” Bradley Snyder was to write in the American Alpine Journal. In 1981 Waterman, a victim of psychiatric breakdowns, disappeared on a solo attempt of the East Buttress of Denali. His mission, taking little gear in a heavily crevassed area and amid active avalanche terrain, is considered a probable suicide.

In the 1980s Patrick Berhault, Christophe Profit, Bertrand Couzy and others soloed routes in the Alps in record times, and undertook massive solo enchainments. Berhault, a close friend of Patrick Edlinger who helped develop sport climbing in Europe, died in 2004 at age 47 on the Dom in Switzerland in a bid to link all the 4000-meter Alps. He was with a partner but unroped at the time.

In 1990, Alain Ghersen (France) linked the demanding American Direct on the Dru, the Walker Spur on the Grandes Jorasses, and the Integrale de Peuterey, Mont Blanc. Ghersen also competed in World Cup competitions, even making a podium.

Alison Hargreaves (UK) was another prominent solo climber in the Alps in the 1990s, though she is best known for climbing Everest alone and unsupported, without supplementary oxygen, in May 1995. In August Hargreaves and five companions including Rob Slater (USA) were lost in storm high on K2.

Mark Twight is a photographer, author and trainer who was a professional ice climber from the late 1980s until 2000. Among his many leading ascents, in 1988, he made a two-hour solo of the 3,000-foot Slipstream (Grade 6) ice climb in the Columbia Icefields, Canadian Rockies.

Mark Wilford, Charlie Fowler: were the first Americans to solo the North Face of the Eiger, in 1988 and 1992 respectively. Wilford, in a long and varied climbing career, also soloed the North Face/North Ridge (VI 5.9 A3), of Mount Alberta in 1991.

Colin Haley has many mountain soloes to his credit, especially in Patagonia, the Coast Range, B.C., and the Alaska Range. They include Supercanaleta on Fitz Roy at age 24 in 2009; the first solo ascent of Torre Egger, in Patagonia, 2016; the Infinite Spur, Mount Foraker, 2016, speed record; and the Cassin Ridge, Denali, in a speed record (8 hours 7 minutes), in 2018. See this account.

Ueli Steck (Switzerland) speed soloed the 5000-foot North Face of the Eiger in 2 hours 22 minutes in 2015. The much-awarded author of a multitude of mountain soloes, Steck died at age 40 on an unroped training climb on Nuptse in 2017.

Marc-André Leclerc (Canada) was one of the great alpinists of a generation, at age 25 already responsible for enormous breakthroughs. Leclerc soloed comfortably on rock on long and short rock routes at his home area of Squamish, yet is best known for the historic soloes of the Emperor Face on Mount Robson, steep mixed routes (including Nightmare on Wolf Street) on the Stanley Headwall, the Northeast Buttress of Slesse in winter, and Torre Egger in Patagonia. He and the respected Alaskan climber Ryan Johnson disappeared in March 2018 descending from the North Face of Main Mendenhall Tower, the Juneau region, Alaska.

See the superb contemporary film The Alpinist, now streaming. The Alpinist is up for a Sports EMMY for long documentary, to be determined on May 24.

See this profile.

Laura Tiefenthaler (Austria): second woman (as far as known) to solo the North Face of the Eiger, in 2022. She rope soloed 10 pitches on the 6,000-foot face. See this account.

Biography

See David Smart’s Paul Preuss: Lord of the Abyss: Life and Death at the Birth of Free-Climbing, a biography of Paul Preuss (Austria), 1886-1913. Preuss was a very early advocate of solo ascents, believed in ethical purity, and eschewed use of technological equipment. In his lifetime he filled lecture halls, speaking on alpinism.

Preuss died at age 27 on an attempted solo ascent of the North Ridge of the Mandlkogel, in the Austrian Alps. He was said to believe that soloing was safer than climbing as a party, as while soloing he did not put a partner or belayer (using the equipment of the era) at risk.

David Smart is founder of Gripped: Canada’s Climbing Magazine.

Other Genres

- Deep-water soloing, done on rock walls on seacoasts or above quarries or rivers. Among early innovators were Miquel Riera of Mallorca, Spain (see Psicobloc in Dosage 2, Reel Rock), who was later lost to cancer, and Chris Sharma (see King Lines), longtime leading American climber.

- Buildering, as done on buildings (often on campuses) and bridges. Two skyscraper climbers have been Dan “Spider Dan” Goodwin and (from France) Alain Robert, “the French Spider-Man.”

- Roped soloing, with the practitioner climbing alone, whether on a short cliff or a route on El Capitan or other big wall.

- Highball bouldering: goes beyond the usual bouldering heights of 10 to 15 feet to a height where a fall would have severe consequences, such as 20 or 40 feet. A near mythic example is John Gill’s ascent of the Thimble, in today’s parlance given V5, on a pinnacle rising 30 feet above a roadway pullout in the Needles Eye area, Custer State Park, South Dakota. In his bouldering history Stone Crusade, John Sherman wrote, “When Gill ascended it in 1961, it was the hardest route of its length or longer in America.”

Slang

Soloing is sometimes referred to as third-classing, after the Yosemite Decimal System. Class 1 is hiking, Class 2 is difficult hiking, Class 3 is scrambling using hands but not yet a rope, Class 4 means roped, and Class 5 is technical climbing, with ratings from 5.1 to 5.15. The upper grades from 5.10 on are subdivided into four categories: a, b, c, d. The term “third-classing” is used somewhat humorously.

Unexpected fact

Tony Scott (UK, then USA), top-drawer director of Top Gun, Crimson Tide, The Taking of Pelham 123, and other action films, was a climber, especially active in his early years, and once soloed the famous Cenotaph Corner, Llanberis Pass, North Wales. The route, an open book set high on the pass hillsides, is a sustained 5.10, with the hardest and most insecure moves (face moves rather than in the corner-crack) at the very top. He died at 68. Read this account.

See also an entry on Tony Scott in Climbers We Lost 2012.

Free soloing has a particularly long history in the UK, back into the 1800s.

Early hard scrambles

John Muir did a lot of solo wandering and Class 4 type scrambling to climb peaks in the Sierra. When he climbed the north face of Mt. Ritter in 1872, he found himself stuck halfway up a cliff face. As he wrote here:

“After scanning its face again and again, I commenced to scale it, picking my holds with intense caution. After gaining a point about half-way to the top, I was brought to a dead stop, with arms outspread, clinging close to the face of the rock, unable to move hand or foot either up or down. My doom appeared fixed.” Yet with a burst of clarity, his mind took over, and he surged on. “My trembling muscles became firm again, every rift and flaw was seen as through a microscope, and my limbs moved with a positiveness and precision with which I seemed to have nothing at all to do.”

More history and philosophy:

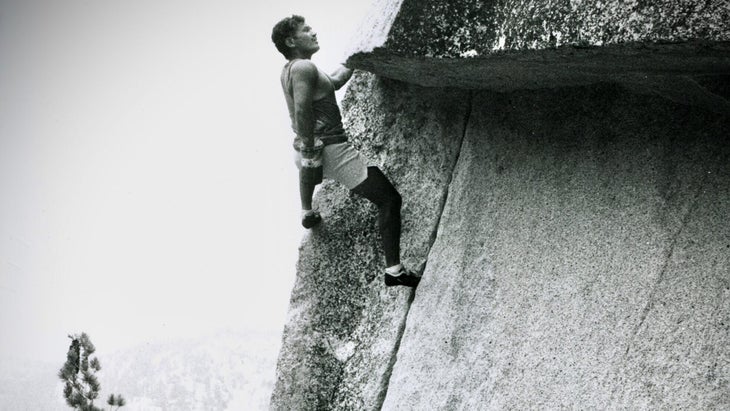

Royal Robbins (1935-2017), pioneering and revered Yosemite and California climber, was also known for soloing on rock. Robbins, thoughtful and scrupulous to the point of rectitude, kept his particular soloes mostly quiet at the time, but wrote about his philosophy in his classic book Advanced Rockcraft.

Pat Ament later enumerated the soloes in his book Spirit of the Age: Royal Robbins.

Taking place in the early and mid 1970s, they included many 5.10s including the offwidths on the right and left sides of Reed’s Pinnacle, done in Tretorn sneakers. “This was,” Ament wrote, “arguably, the highest standard of free-solo climbing in the world at the time.” Robbins also soloed Moby Dick Left Side, Crack of Despair, and the multipitch East Buttress of El Capitan, all 5.10, plus innumerable 5.8s and 5.9s. (He did the North Buttress and Direct North Buttress on Middle Cathedral with self belays.)

From Robbins’ own Advanced Rockcraft: “One must never take a chance soloing; never try something unless one knows one can do it. ….[T]here is no merit in succeeding through luck ….

“One of the most persistent hazards of free soloing is climbing into a position from which retreat is impossible. … It is imperative for the soloist …not [to] make moves he cannot reverse. …

“The terrible thing about free soloing difficult routes that are within one’s capacity, is the chance that faced with the ultimate danger and need for ultimate self-control, one’s nerve might fail and cause an error. That’s the irony of it—that fear could short-circuit skill, that one would die as a direct result of being afraid to die.

“So before you take leave of your friends, consider well the seriousness and possible consequences of going alone.”

See also:

This film on deepwater soloing.

Read also:

Opinion: The Free Solo Documentary Addressed Some Uncomfortable Truths, But Ignored Others

A point-of-view essay (by the author of this compilation) against the practice of soloing: Things We Shouldn’t Have Done: I Regret Ever Free Soloing

Rolando Garibotti: What I’ve Learned, a thoughtful interview with a leading climber and historian who, among other subjects, discusses past soloing, saying in part: “In retrospect, if there was something I wouldn’t do in my life, it would be that.”

Competitive Free Soloing in the Gunks, from 1985, by Russ Clune, with a new preface: “The feeling of unencumbered movement is just plain fun. But I am painfully aware that most of the true soloists of my generation died soloing. … If you keep pushing, eventually there will be pushback.”

Here is a humor piece by Ron Amick on an ill-advised endeavor: “Things We Shouldn’t Have Done: Tried to Solo Swan Slab That Night.”

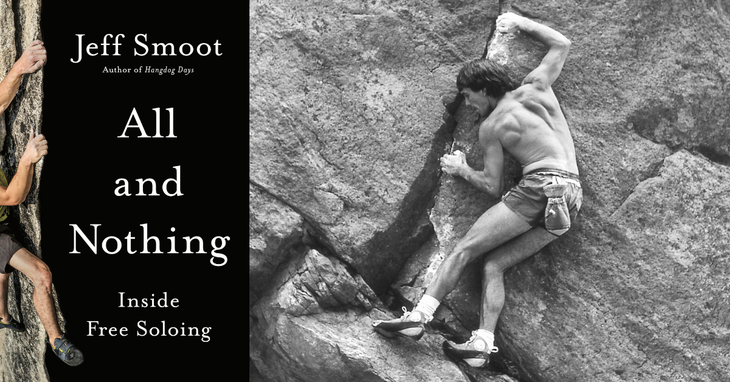

Here is a link to information on the new book All and Nothing: Inside Free Soloing, by Jeff Smoot, a 320-page history published August 25 by Mountaineers Books. Jeff Smoot is also author of Hangdog Days: Conflict, Change, and the Race for 5.14.

Read also, “I tried to Do More With Less”: A Chat with Famed Soloist Henry Barber.”

Here is another online compilation on free soloing.