Guidebooks Are Still a Problem

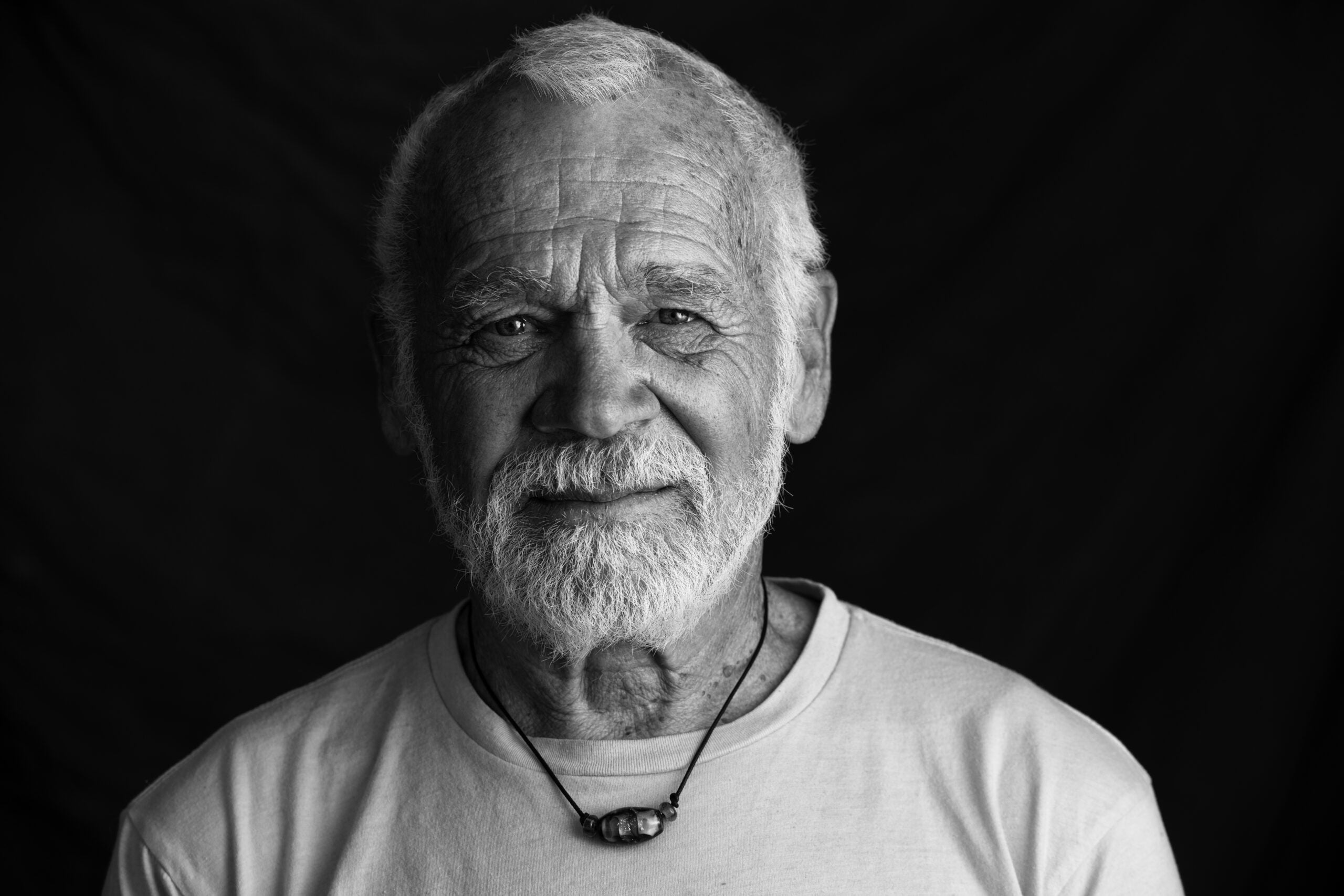

(Photo: David Clifford)

My favorite note on a topo came from a guide buddy, Todd Vogel. Next to his line drawn up a particular pitch he wrote, “A little weird here.”

Get there and anything could happen, but at least you’ve been warned. It’s advice that could apply to using any guidebook. The convolutions of the natural world don’t lend themselves to two-dimensional linear representation. … Here’s a story.

So we drove into Boulder last fall, prime climbing time. We had eight days, an Airbnb. We went straight up to the Third Flatiron to warm up. That would be my fourth time up it. We carried the Flatiron guidebook from California. It’s satisfyingly dog-eared from being stuffed into climbing packs. I know the Chautauqua—I love saying that word—trails, a little. Hiking up out of the parking lot over meadows can feel like The Sound of Music. So classic you half expect to see Julie Andrews skipping along holding the sides of a flouncy skirt. Or maybe John Denver will offer you a joint.

Our chosen line was lesser known, furthest left along the slab. And we got lost.

Our fault, maybe, for desiring a whole new approach to a familiar place. We switched to Mountain Project to get us there. But, nose to phone, we couldn’t decipher the directions, where one wrong step off a steep sidehill trail and climbing wouldn’t be an option, for a while.

How far is 200 yards when it’s so steep? All we knew for sure was that we needed to cross this ravine. We improvised, finding a spot where we could barely descend without rapping, and managed a creek crossing on the third try by scuttling over a humongous chockstone that’s “only” 4th class.

I won’t go into the bushwhacking that followed. The climb itself was really fun. Descending, we were grateful at last to read word-for-word directions to the rap chains. And happy to squeak through the steepest talus below on a well-built trail before twilight shut us down. The Access Fund had clearly been there, because a chaos of talus was subtly reworked into heroic-sized steps. Nice! Also nice was the sumptuous choice of brewpubs and the Sherpa-owned restaurant we settled on.

That little scene underscores my first takeaway about guidebooks: The rough approach wasn’t a guidebook (or app) problem at all. It was a mountaineering problem. It took replaying that realization over our first beer to fully understand. But truly, it’s an easy, knee-jerk response to slide into the blame game. Stupid guidebook! Inept Mountain Project! We would have had an easier approach if we had relied on our innate mountain sense right from the start. Not that hard. We could see the Third, right up there. And how to weave through deadfall is not the kind of problem you should expect even a Strava line to help with. You just figure it out, one high-step at a time. Just go. Instead, we kept searching for clues on the tiny screen.

There’s just a paragraph for each route, some routes being thousands of feet, about one sentence per pitch. It develops a rhythm. There is personality—even quirkiness—in the way those lines get described.

Our own fault? Well, our fault for trusting some stranger’s directions, just a random opinion blurb in the comments strings that are so ubiquitous online. A guy, or gal, of unknown skill and questionable authority. Which leads directly to the most infuriating thing about that venue: It is overstuffed with info written by amateurs of geography and climbing. So, yeah, sign of the times.

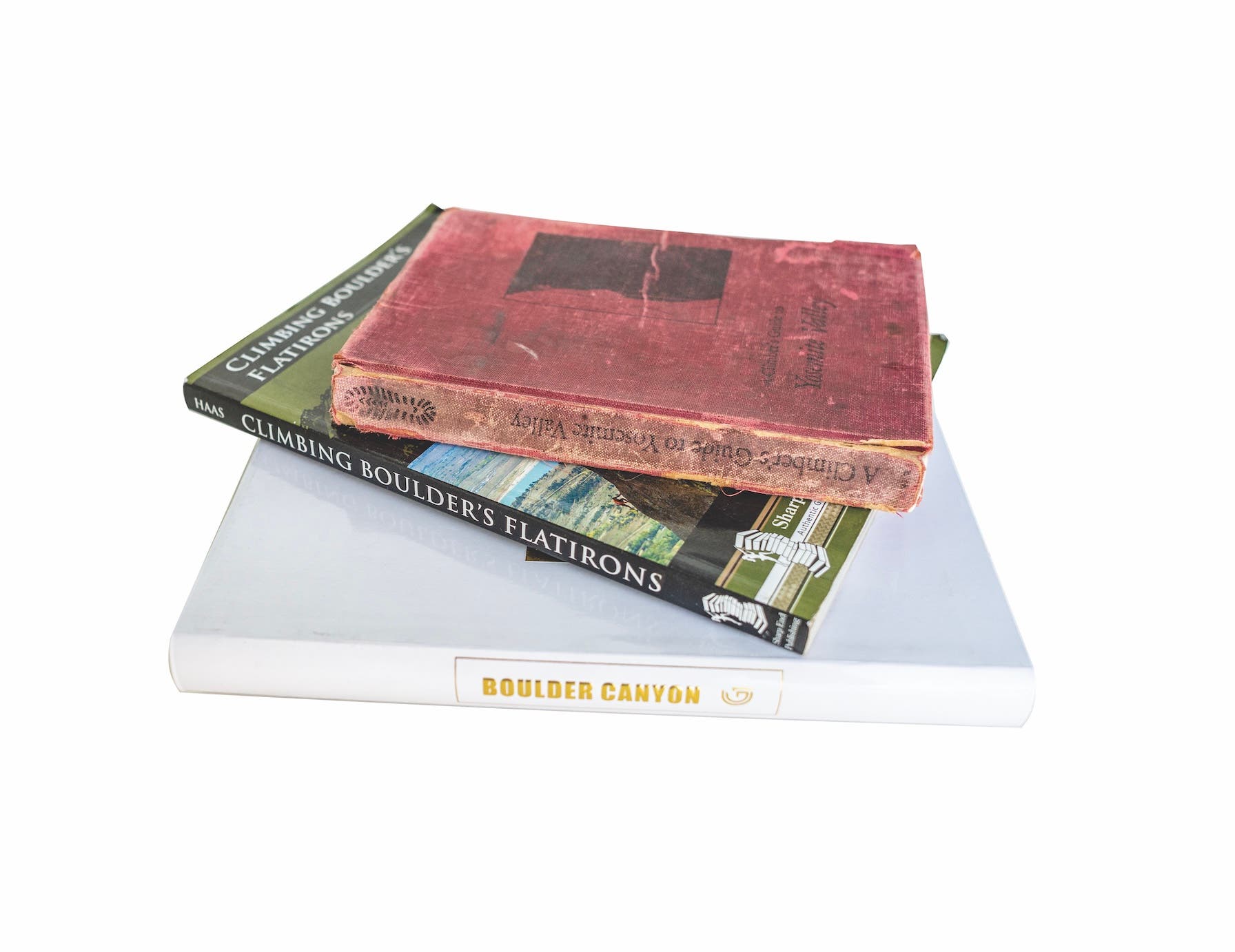

The next morning we were on the steps of Neptune Mountaineering as it opened. There are two bookcases of guidebooks. Good advice at your elbow is one of the best things about a great shop. Oh yeah, also, my girlfriend, Eva, wanted a new climbing pack. I wandered off and found ski boots … on sale! Hours later, no pack and sans ski boots, we walked out with four new guidebooks. $140 bucks. Once upon a time, when guidebooks cost less than a six pack, most of my road trip money could get saved for beer.

One of our new guidebooks was so odd, right on the face of it, I couldn’t get past the cover. It felt outlandish in the mode of guidebooks-have-come-to-this, yet it’s one of those that came recommended by great staff, the latest on Boulder Canyon. No typical rad-dude-color photo. It was stark white. A pearly shine. With the title in raised gold letters, weirdly like a bodice-ripper novel. I half expected to open it to a mushy inscription by Tammy Faye Baker. Its meta-message, though, was disturbing: too fine a volume to toss in your pack and actually use. It might become soiled.

Inside it looked perfectly fine, thankfully. Unfortunately, we didn’t get to test-drive it because the road up Boulder Canyon was all torn up, and the pullout for our chosen route was blocked by honking-big machinery. Reminded me of the joke about mountain towns having two seasons: winter and construction. We moved on to Lumpy Ridge, opening another of our fresh new guidebooks.

If all this strikes you as a yawn, here’s a contrasting experience from when I was 19. Yosemite Valley, 1964, and the very first guidebook to the place, Steve Roper’s A Climber’s Guide to Yosemite Valley, was hot off the press.

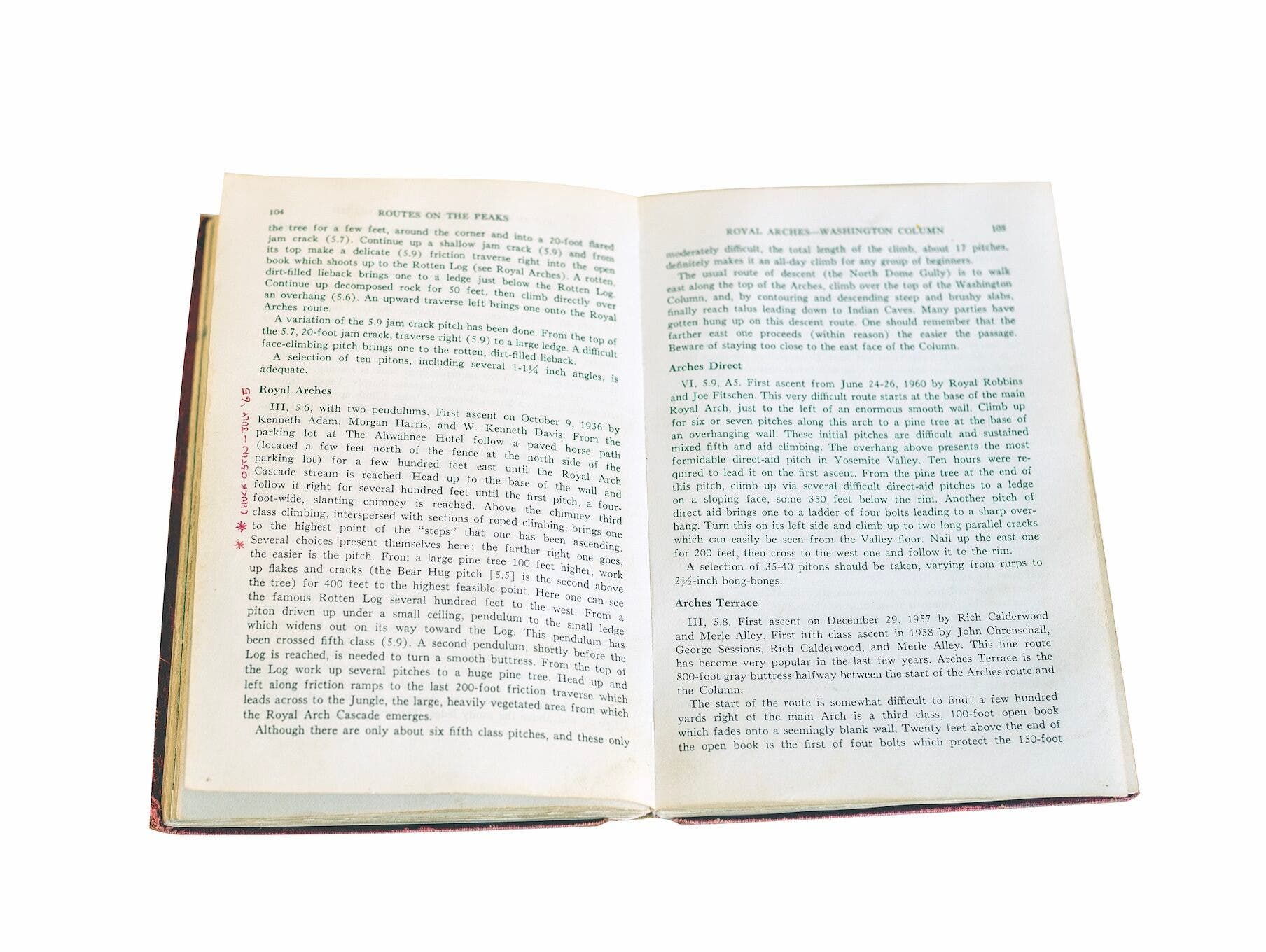

My copy has been well-loved. It has climbed hundreds of thousands of feet in my pack—and don’t get me started on leather-bottomed, metal-buckled canvas packs. Roper’s guide doesn’t have a topo in sight. That won’t be invented for 15 more years. There’s just a paragraph for each route, some routes being thousands of feet, about one sentence per pitch. It develops a rhythm.

There is personality—even quirkiness—in the way those lines get described. No gear recommendations. Plenty of adventure lurks, generously interpolated between landmarks. All route descriptions settle into their own rhythm, and become part of the learning curve for a climbing area.

In 1966, I moved on from the Valley to a different area and promptly got sandbagged. The Teton guidebook was way fatter, which should have been my first clue. There was a totally different rhythm to the descriptions. High on the Normal Route of the Grand, I climbed right past a famous move I’d been looking forward to, the “Belly Roll Almost,” because it was described in a much wordier mode than I expected. I hadn’t adjusted, not realizing I needed to.

Speaking of Wyoming, I went on to the Wind Rivers. Got up classics in the Cirque of the Towers. I was starting to get used to those routes being translated onto paper by yet another author new to me. I was falling in love with a new mountain range, which then led to one of the rudest guidebook shocks of my life.

A week later, we were done, sated. We began walking out, not even driven away by a lightning storm. And then there it was: a 700-foot wall sliced by a Yosemite-style crack system. Unclimbed. We dropped our packs.

I won’t bore you with a gosh-and-golly account of my very first first ascent. It was fun and satisfying, but this is about the guidebook incident that spun out of it. Proudly, I named our new line. Now remember, this was the Sixties.

Earlier, back in Camp 4, Sheridan Anderson, our very-own resident-troublemaker cartoonist, had proposed an outlandish guidebook note about needing an extra left klettershoe. So, in his honor, our route became Andy’s Only Extra Left Klettershoe Chimney.

I wrote it up, and sent it to … an address in Texas? Maybe that should have been a warning. Yes, the husband and wife guidebook authors were from Texas. And, just perhaps, California humor was beyond them. The Cirque of the Towers was coming into its own as a destination in those years, so in 1968 a new edition of their guidebook appeared. There was my route. Or was it? My route name had been abbreviated to “Klettershoe Chimney.” Bland and stupid. And the climb was on a different peak. What?

Fortunately, those two never wrote another guidebook. Dude was a lawyer … what can I say? Guidebooks were their side hustle.

But the really fortunate thing, for all of us, is that Joe Kelsey took over. O.K., I’m totally prejudiced here. The Wind Rivers are the second-finest mountain range on earth—I’m from the Sierra and prejudiced—and Joe Kelsey is one of the most literate, knowledgeable, devoted and downright funny guidebook authors who has ever lived. His notes on geology alone are as sophisticated as you’ll find anywhere, and his Golden-Retriever-scale for defining third class climbing is totally unique. If his dogs figure it out, it’s third class; if not, fourth.

Kelsey has spent his entire climbing life in the Winds, and—here we’re lucky again—he has recently expounded on the fullness of his experience. It goes way beyond being a guidebook author, though that’s in there too. He summed it up with tons of rich stories. And attitude. Look for A Place in Which to Search. It’s self-published, so you’ll have to, well, search for it. You’ll be rewarded by one of the best climbing memoirs ever, starting with Joe ducking out of college to become one of the legendary Vulgarians in the Gunks.

Guidebooks have changed. It’s not so much the slick paper and color photos. Those are nice. It’s the stories creeping in among the routes that I really like. The lore of climbing. Who stumbled upon this place? What was its very first route like? Tell me an epic. Or three. Tease me. I think of a newer guide to Indian Creek. I got to contribute a story of driving along those cliffs before their time was ripe to become a major climbing area, and I love rereading the story about the FA of Super Crack of the Desert (and its original name …). A bold lead on hexes, shortly before cams opened up the place to mere mortals. This is how guidebooks have become more like a good climber campfire.

That guide to Boulder’s Flatirons has ’em, too. Great stories. There’s an armchair chapter about vying for the record, round trip from the parking lot, on the Third. And a classic photo of snow climbing its face, battling upward with an ice axe.

Mountain Project—it’s free!—is now a major force in the “guidebook” world. It has helped us get to a number of crags too new to be in print. And digital can bring up-to-the-minute information, even though lots of yammering in the vein of my-opinion-is-vital-even-though-I’ve-only-climbed-six-routes-ever needs to be filtered out, big time. I don’t need your excruciating beta to drop a #4 in there, and would rather savor whatever sequence awaits me above.

I hate the idea of locating climbs by GPS. It’s not just, like texting at 75 miles an hour, that distraction-by-a-screen can be bad for your health, and sharply curtail your longevity.

Last fall, I went to Suicide Rock. Eva has this gig, doing IT work for big law firms, the kind with maybe Google for a client and offices all over the country. So when we left Boulder she flew to San Diego for a few days, and I got to drive across the West, one of my all-time favorite things. On her next break we climbed at Tahquitz and then Suicide—her first time.

I’ve been going there for over 50 years and looked forward to repeating classics. I headed back to Suicide Rock’s Weeping Wall. Only I couldn’t find it. I guess it has been a while. I’ll spare myself a lot of embarrassing stumbling around and a false start after trying to convince myself that this slab here looks sorta like it. It went on for hours. Finally, Eva pulled out her phone, hunted down a weak signal, dialed up Mountain Project and got us there in time for a few quick laps before dark. “Follow the guide”? Yeah, right.

And there are other, “authored” digital apps (for a well-deserved fee) that bring all the brilliance of traditional guidebooks, plus the convenience of updates and other tech features, to your handheld. Check out the Gunks App.

But still, I hate the idea of locating climbs by GPS. It’s not just, like texting at 75 miles an hour, that distraction-by-a-screen can be bad for your health and sharply curtail your longevity in so many ways. It’s not remembering to download from WiFi when your attention is on counting draws and filling the water bottle. Really, it’s about fondness for adventure. Exploring. Then again, my attitude is frankly so creaky, such a throwback and who-cares irrelevant in this handheld age that it doesn’t count. Can you stomach another lost-in-the-woods story from a bearded woodsman who’s climbed at (insert crag here) for 50 years, is a full-on certified guide and should know way better?

Yes, I’m fully certified, but I can get just as lost as anyone on new terrain. My credentials ain’t magic, and mountain terrain can be devious. Stumbling around in steep brush again … same as it ever was. That goes for straight-up rock areas too. My rule of thumb is this: Allow half a day to get oriented to a new area—not climbing, just floundering—while you get on the wavelength of a new place and a new guidebook author.

Wondering about the TITLE to this piece? “Guidebooks Are Still a Problem.”

Still a problem? Forty-odd years ago in this very journal, the editors arranged a debate about guidebooks between myself and Royal Robbins. They labeled it “The Guidebook Problem.”

It wasn’t about guidebooks screwing up places by bringing in hordes of climbers, even though those storm clouds were already forming back when there were a thousand times fewer climbers than we have now. And it wasn’t about inherent deficiencies in the whole guidebook genre either, the kind I’ve been talking about here. No, it was because some of us in the Sierra had stopped reporting new routes entirely. Didn’t write them up at all. We weren’t hoarding our “secret spots” either. Rather, it was a hippie-Buddhist concern about ego, about the danger of getting swept away by an inflated sense of self. Hey, did you see my new route? Yeah, I’m so badass … It felt like what happens in skiing where your fresh tracks in powder are visible from the bar. Instead, we wanted to refocus, hoping to revel in a sense of purity, savor the experience itself.

Royal Robbins was a perfect one to debate in favor of recording your routes for the future. I mean, the Salathé Wall? Iconic. Worthy. And the beta for getting up it has led thousands since its FA to one of the best experiences of their lives. The climb didn’t just accidentally start getting called “the finest rock climb on earth.” So, I guess I was destined to lose that debate.

Plus, I began to notice that I looked forward to going to a new area and being led to the most classic lines, rather than mistakenly gunning for some shit route up a brushy gully that had thoroughly earned its obscurity. There’s a good reason I now have a five-foot shelf of guidebooks right at my elbow as I write this. And another five feet in the next room, including older guides to well-loved areas like Joshua Tree, and ones to equally well-loved spots I just won’t get back to very soon, like the English gritstone. In the end, I had to admit to myself that I use guidebooks all the time, that I like them. Only then can I get over myself, and my self-righteous stance about not reporting routes.

Besides, there’s one line from that hush-hush era I’d like to find again. On the Incredible Hulk, which has rightfully proven itself to be one of the finest Sierra areas, Mike Farrell and I put up the second-ever climb. Unlike all the others, it goes directly to the summit, which in the cragging spirit of climbing there, matters not at all. We didn’t name it. Why bother when you ain’t reporting?

Well, decades later, someone put another line on that facet of the Hulk. There’s a good chance they’re the same climb. And why not? Crack system shooting toward the summit, bordered by the orange granite that hallmarks among the best, most featured face-climbing in the Sierra. With ours never published, that wall was just waiting for a “FA.” They ended up the same difficulty; the new route is called Falling Leaf. Mike, whose memory is less fuzzy than mine, even drew me a topo. At only 5.9—I think we even rated it an old-school 5.8—it could open up the fun of the Hulk to less experienced climbers. Definitely worth a trip to go check it out again.

I was the first to push climbing development in the Buttermilk Boulders. For a few years, my Armadillo clan would live out there days on end, exploring, partying, and putting up lines. Now several guidebooks lead tens of thousands to a truly worthy experience.

These days when I go out to the Buttermilks, most everyone I run into is new. Which is great. We can share some beta, shake our heads and grin in gratitude for the bounty of this planet—starting with rocks and sunshine. We have climbing in common, and that’s plenty to build community around. I often think of what Phil Lesh of the Grateful Dead once said, looking out over a sea of us Deadheads at one of the innumerable concerts we’ve shared, starting the year before I wrote my first article for Ascent, 1967: “Without this community, hey, what good would it be?”

Doug Robinson is a professional mountaineer known for his climbing, guiding and backcountry skiing, as well as his poetic writings about the mountains.