Pride Hasn’t Always Been Easy: How I Learned to Accept Myself As A LGBTQ+ Climber

This article was first published in 2021 and is being re-published in celebration of pride month.

Being a little bit different is something that I feel a lot of climbers can relate to. We’re a community that’s often drawn together not only by our mutual love of scrambling walls, but by a sense of belonging that we find within the sport. So many of us discover a like-mindedness amongst climbers that we’ve struggled to find in other facets of our lives. For so many outsiders, climbing is our niche. Whether it be through our sense of adventure, the collaborative psych that goes into sending a project, or just sharing the joy of climbing movement, we fulfill our need for connection at the gym or the crag. It’s something that is so crucial to our social and mental health—finding home in a place or a group of people with which we can share a common sense of identity.

I knew that I was different from quite a young age. As the kids around me grew older and started seeking the interest of the opposite sex, I just couldn’t relate to them in the same way. From as young as 7 years old I knew that I didn’t feel the way about women and girls that everyone had told me I was supposed to feel. As I grew older, it became apparent that an attraction to women was not something that I would just grow into as I matured. And yet, no matter the inevitability, I would push these feelings into a deep denial. As a young boy, being gay just did not feel like an option. No one had expressly told me this, and yet the feeling prevailed. When I grew up I had to fall in love with a woman, we would have a family, and that would make me happy. I would do just as my parents did, and their parents before them. I would find the same qualities in their friends, see it in the people on T.V and in movies, read about it in books, and hear about it in music. They all shared a common heteronormativity that I felt I also needed to conform to if I wanted to lead a fulfilling and satisfied life. At 11 years old, it became a secret that I was intent on taking to my grave.

Through my years at secondary school I made every effort to conceal my identity. At times it felt like the most important job I had to do everyday was to mask various aspects of myself in order to fit the mold shaped by the other boys around me. And yet, no matter how hard I tried, it was never enough to deter the chatter. By the way they treated me or the names they called me, it became increasingly evident that I couldn’t hide. They weren’t always so blunt or abrupt, but I could always tell they knew that I wasn’t quite the same as them. At times even my teachers would appear puzzled by the way I simply didn’t affirm the stereotypes they came to expect from an athletic teenage boy. There has always been a strong degree of both masculinity and femininity in the way I behave and present myself. Naturally this would lead to people making assumptions about me. No matter how hard I tried to skew my mannerisms and personality in favour of their expectations, I could never quite get it right.

I had always hoped that through this sport I would find a haven of strong, queer climbers within which I could foster the sense of belonging that I had always yearned for. As I grew older I increasingly felt that this was not the experience I was going to have. When it felt like the right time I began to tell my friends both in and out of the climbing community, as well as certain family members, about my sexuality. I did this through my teenage years and into my early adulthood, and whilst they were always supportive, I nevertheless couldn’t shake this persistent feeling of otherness. In the gym, at the crag, and around the campfire, I would be endlessly probed with generally well meaning but ultimately tiresome questions. These questions would range from how I came to know what I was and my experience as a gay man in the climbing scene, to whether or not my parents were approving of my “choice” to be a homosexual. I did my utmost to educate and inform the people around me, but often found myself longing for a place where it wouldn’t feel like this responsibility fell solely on me.

At that stage of my life, a community in which I would find others that I could fully relate to and see myself in seemed like a far-off dream. I believed that I was at peace with my identity as a gay man, but in hindsight I still hadn’t yet reached the point where I truly saw this part of myself as worthy of love. Without really knowing it, I needed to be able to see people just like me, queer people, at the top and succeeding at life with passion. To see them not just as distant, controversial figures barely worthy of basic human rights like getting married or starting a family, but as whole members of society who can kick goals and be role models. I think it can be such a foreign concept to many that fit into cis, straight, or white majorities that being different can deprive you of such strength and confidence. But when all of your life almost every notable queer person that you’ve seen has had to conceal such a crucial part of themselves to get to where they are, it’s easy to convince yourself, without fully realising it, that you will have to do the same. This felt particularly evident in sport, and as such I always felt that these two parts of myself were juxtaposing one another.

It really crept up on me and took me by surprise when I reached a stage in my life where all of this began to change. A few years ago a newly formed queer climbing association called the ClimbingQTs reached out to me and expressed their interest in having me speak at a panel discussion event they were holding. It was admittedly a bit of a dice role on their part, as despite me not necessarily keeping my queerness as a secret, there was very little on display in my public life that affirmed my homosexuality. Despite the suspicions that I’m sure they held, I was yet to outrightly tell my parents that I was gay, and as such this event presented me with a very unique challenge. Accepting this opportunity would mean taking a massive step in not only accepting myself, but presenting myself to the world in a way that I’d never done before. I reflected on the themes of my youth: the desperation with which I would try to hide who I was, and the longing I held for someone else in the community that I could look up to. I realised very quickly that I felt a strong intrinsic responsibility to be that person for other young and potentially struggling queer people. With all of the things that I had accomplished, I had a powerful opportunity to be that person for others—the one who would wear their queerness with pride and honor alongside their accomplishments, not in spite of them. Nervously, but with little hesitation, I made the decision to take up this opportunity.

I wish that I could have had a glimpse at the ways in which this would change my life for the better. Perhaps knowing this would have eased my nerves, because I couldn’t shake the subtle feeling that maybe I was making a mistake. I held fast and took part in the event, with my parents supporting me from the audience alongside my friends and various other queer members of the climbing community.

It was in this crowd that I saw a network of LGBTQ+ climbers and allies with a greater degree of visibility than I had ever witnessed before. The event definitely led to some deep and meaningful conversations, as my progressive parents struggled at times to understand why it had been so hard for me to share this part of myself with them, but simply sitting up on that stage with a microphone in hand and professing who I was was a powerful affirmation to myself. It opened the door to the kind, compassionate, and bold LGBTQ+ climbing community that I had all but given up hope of finding. In this group of people, I discovered the means to love all parts of myself and truly come to understand what it is to have pride. Queerness is not a deficit that I was unfortunate to be born with, it’s an asset that both sets me apart from the crowd and connects me to so many others. By embracing myself as both a gay man and an athlete I have the ability to assure young people, who may be feeling the apprehension that I did, that gay people are not only all around us, but we don’t have to hide who we are to get respect. We come in all shapes and sizes, and the value that we have to offer to the world has no limits.

If I could go back and speak to my younger self, I wouldn’t necessarily tell him to do anything differently. Whilst it was not that long ago that I was at school, in many ways it was still a different time. I would, however, remind myself that every giant leap I was too afraid to take would one day look smaller, and that my queerness would become something that brings both strength and joy to my life. I never understood as a young person when gay people would profess no desire to change who they were. With the help of my community, I’ve come to understand the ways in which this part of myself has shaped me and allowed me to grow into the person that I am today. I’m exceptionally lucky to have a group of fiercely loyal friends and a loving partner that mean the absolute world to me, and I couldn’t have come to this point in my life without learning to love and appreciate my queer identity. It’s not always easy, and there will always be people who see it as their place to disrupt your sense of self, but a strong community is one of the things that allows me to hold fast in my pride. This community is without a doubt one of the most formative gifts that climbing has given me; a gift of courage and self love that I hope I can have the privilege to be able to pass on to others.

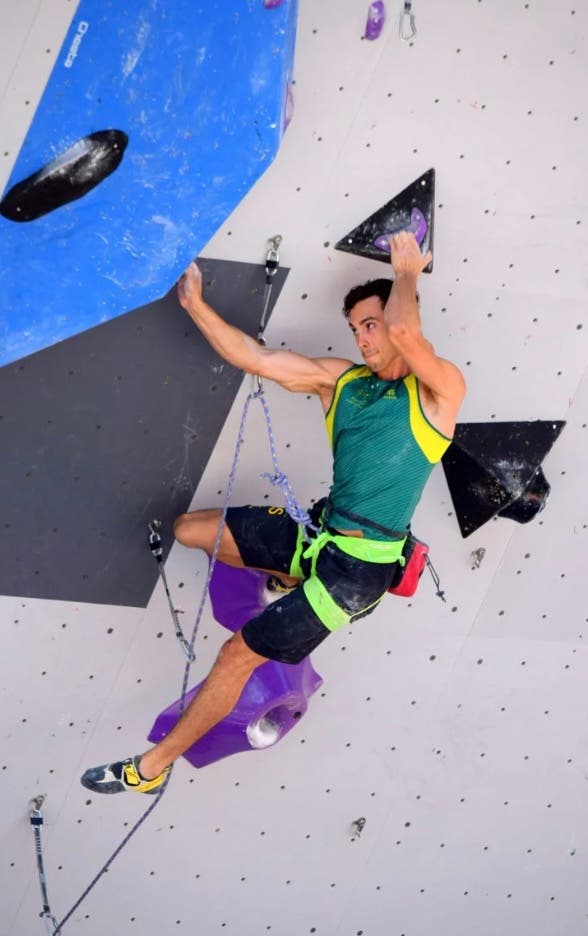

Campbell Harrison (he/him/they) is a 25-year-old competition climber living in Melbourne, Australia with his partner Justin. He has been a member of the Australian National Team since 2012. He can be found on Instagram at @campbell_harrison547.