Into the Vast Unknown

"Charley-Mace-West-Shoulder-Headwall-Mt-Everest"

[Broughton Coburn’s The Vast Unknown: America’s First Ascent of Everest—to be released on the 50th anniversary of the historic expedition—recounts the epic climbs, the men who pulled them off, and how they inspired a generation. This is a short preview of the acclaimed book, distilled from his account of the first ascent of the West Ridge, which is still regarded as one of the greatest climbs in Himalayan history.]

Click here to read bios on the major players mentioned in this sneak peek.

Click here to read interviews with Jim Whittaker and Tom Hornbein.

A half-century ago…

As a teenager in the fall of 1965, I was transfixed—along with 20 million other American viewers—by the first-ever National Geographic TV special. The flickering images, viewed on black-and-white sets by most, showed shaggy men with grizzled beards and blistered skin forging up impossibly steep Himalayan slopes. The glaciers and crevasses were frightening. Looming above, Everest’s summit glowed with an otherworldly aura.

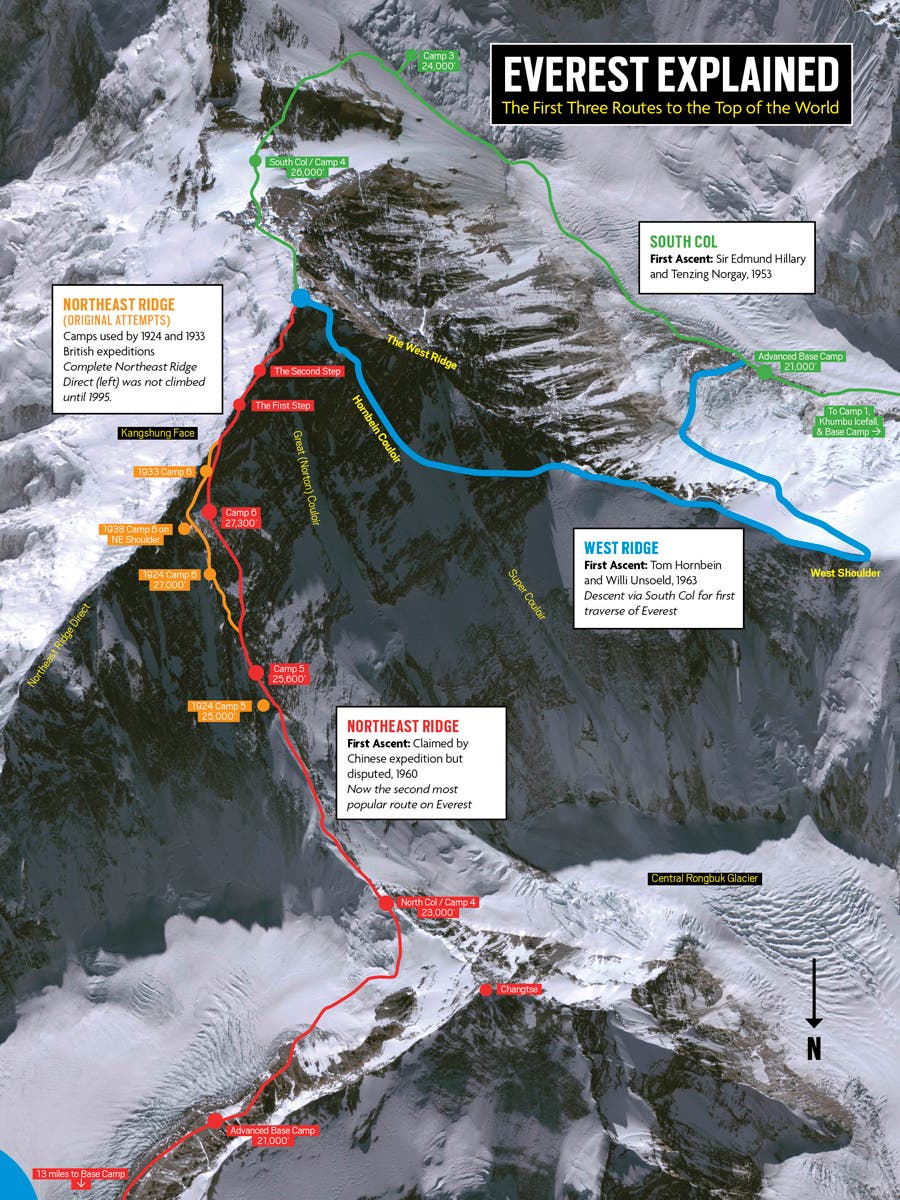

It had taken America a while to get there; in the 1960s, the U.S. lagged behind most of the world in mountaineering. The British and Swiss had reached Everest’s summit a decade earlier and basked in glory across Europe. But the Russians, who had dominated in two previous Olympic Games, hadn’t climbed it. And although the Chinese said they had placed three climbers on the summit in 1960, their claim was dismissed, and it’s still disputed by some.

America had an opening—albeit a narrow one—to beat the Russians to the top of Everest, if not to the moon. Failure, of course, would mean global disgrace. The U.S.—despite its trademark optimism—was struggling with loss, confusion, and an identity crisis. Who were we? Might America fall into second place as a world superpower? We needed direction.

That changed on May 1, 1963 (at least in a small way), when Jim Whittaker of Seattle and Nawang Gombu of Darjeeling, India, became the seventh and eighth people to stand on Everest’s summit. Three weeks later, Lute Jerstad and Barry Bishop followed them, also summiting via the Southeast Ridge. Three hours after that, Tom Hornbein and Willi Unsoeld traversed Everest’s summit, having made the first ascent of the West Ridge.

A week earlier, a tiny space capsule named Faith 7 had lifted off from Cape Canaveral, Florida, atop a massive Atlas rocket. Gordon Cooper, an astronaut with Project Mercury, had survived the longest space flight to date for an American (22 Earth orbits).

These were uncommon men—astronauts and climbers, hybrid scientist-adventurers—who had set out not only to explore, but also to fill in the blanks on the maps of worldly experience and academic knowledge. Everest, like Earth’s orbit, offered a starting point to push this quest into the unknown—and from there to the frontiers of the human spirit. Whether they were aware of it, these men were consummating the diffuse but tenacious dreams of a cautiously hopeful nation.

Concept becomes reality

Some of the team members of the 1963 Everest expedition had a crazy notion: to climb a variation of the mountain’s South Col route (aka Southeast Ridge). Leader Norman Dyhrenfurth calculated that to do so he would need to field a large, well-equipped team. But the concept was too audacious to propose openly during his relentless fundraising campaign, because it entailed tremendous risks—including the risk that the expedition might not reach the summit by any route at all. In spring 1962, Dyhrenfurth hopped into his roadster and drove from the UCLA film school to San Diego to share the idea with Tom Hornbein, who was completing a medical residency.

“Photos were unfurled and laid end-to-end across our living room floor to make a vast panorama, held in place by children’s blocks,” Hornbein later wrote in Everest: The West Ridge. “While I looked at our goal, Norm asked, with a matter-of-factness that seemed irreverent to the highest mountain on earth, ‘What do you think of trying the West Ridge?’”

Dyhrenfurth initially suggested that they climb via the “standard” South Col route, and then descend via Everest’s untouched West Ridge. It was an elegant, if daredevil, enterprise that even the Europeans might envy. Feasible or not, Dyhrenfurth had Hornbein hooked on the West Ridge idea.

Soon, several others were intrigued, and during the expedition’s approach march, lively discussions broke out about its possibility—and how much of the supplies could be dedicated to the effort, and when. It was agreed that a traverse would make more sense if executed in the other direction: up the West Ridge—making it a first ascent—and down via the known South Col route.

A theory that was being studied by the team’s sociologist, Dick Emerson, may have played into the attraction of the West Ridge, too: Motivational investment in a task varies directly with the degree of uncertainty about the outcome. The more certain the outcome, the less motivation there is to achieve it. The West Ridge outcome was highly uncertain, and Hornbein, for one, became fully invested.

Dyhrenfurth tape-recorded the expedition’s daily events in an audio diary transcribed by his wife. Despite suffering laryngitis, he dutifully whispered and croaked into the microphone.

“… It isn’t all lightness, though it is a wonderful team—it’s a strong team. They’re good men, they get along fine, they are all ambitious, they want to get to the summit. And when a person is ambitious, he becomes selfish, and those, for example, who are so eager to tackle the West Ridge don’t realize that when I agreed to split the team into two—if the West Ridge becomes feasible—I automatically signed the death warrant to my own hopes for the summit. We wouldn’t have enough oxygen for as many men to reach the summit if we try two routes, but if we succeed in doing both the West Ridge route and the South Col route, we will have done something unheard of in mountaineering…”

While the advocates for the West Ridge route undertook a reconnaissance, loads were piling up at Camp 2, waiting to be ferried to higher camps. But on which route? In what some felt was an unfair vote, it was decided that most of the expedition’s supplies and manpower should, for the time being, be directed to the South Col route.

Focusing first on a blitz via the South Col was not an irrational decision, considering the demands of the financial backers: Reach the top by any route. Dyhrenfurth had stressed that everyone should have an equal shot at the summit—depending on their physical condition, their own desires, and the prevailing circumstances. Hornbein’s unremitting passion for the West Ridge had caught him by surprise, and Dyhrenfurth referred to him as a “pathological fanatic.” A pattern of irritation grew between the groups advocating each route. Dyhrenfurth hadn’t bargained for being the leader of two separate, competing expeditions.

“One of my major functions,” Willi Unsoeld would later say, “was to keep Hornbein under control.” With the gravitas of his role as climbing leader, Unsoeld could mediate while displaying tolerance for Hornbein (and quietly favoring him). “We would be in full congress, and my job was to sit there, with one clutching claw on Tom’s shoulder, to keep him from tearing the place apart.” Hornbein later pointed out that his single-mindedness might be regarded as “stubbornness” by some and “tenacity” by others.

Time for the West Ridge

Once Jim Whittaker and Nawang Gombu had summited, it was the West Ridge’s turn. But pressure had seeped into Camp 3 West with every radio call from Base Camp. Dyhrenfurth reminded the West Ridgers of their built-in deadline: Porters had been summoned to evacuate the mountain the morning of May 25. The undaunted West Ridge group was making respectable progress, and they had erected their tents at the base of the rocky part of Camp 4W. But around midnight on their second night, May 16, a powerful gust wedged its way beneath the two higher-profile four-person tents. The blast literally levitated the tents—with the climbers and Sherpas inside—and began to carry them down the slope.

“It sounded like a dozen freight trains crashing,” Tetons guide Barry Corbet said. “There was nothing to do other than helplessly try to execute a self arrest, with our fingertips, through the floor of the tent.” They came to rest 150 feet away, perched above the Rongbuk Glacier, which was far below.

“I wondered what I was doing here,” Hornbein wrote, “what insanity had led me to become trapped in such a ridiculous endeavor. The thought was rapid, cathartic: Anybody so stupid deserves to be in a place like this. All three of us were aware of our tenuous hold on the hillside.”

The gale-force winds continued through the next day and blew down Hornbein and Unsoeld’s tent as well—the only one that had remained on the West Ridge proper. The ice-rimed men struggled back down toward Camp 3W and gathered whatever shreds of nutrition and sleep they could.

Quietly, they absorbed the obvious: The West Ridge attempt was over. For one thing, there weren’t likely to be any Sherpas to carry supplies for them. And they couldn’t ask Bishop and Jerstad, who were steaming toward the South Col, for a postponement beyond May 22.

But during nearly two months on the mountain—and many more in thinking and preparation—a pathway up the West Ridge had been grooved in their psyches. Especially Hornbein’s.

The next morning, Hornbein presented a plan that he’d concocted during the sleepless night: They could begin by recruiting any available Sherpas, and then scavenge Camp 3W for equipment and tents to replace the wind-shredded mess at 4W. From 4W, they’d send a reconnaissance team—followed by Sherpas carrying loads—as high as possible up the Hornbein Couloir. This high point would be their final assault camp, 5W. The next day, a single summit team of two would push off from 5W and make one last valiant shot at the summit, eliminating Camp 6W.

“Tom had it figured out,” Unsoeld said. “How many porters we would need, what we could do without, how the oxygen situation stood. Tom’s insomnia was always very productive. And in our weakened condition, it was difficult to distinguish fanaticism from genius. Obviously, it was a kind of hypoxia.”

It was as if a hidden hand had guided the West Ridgers through a gauntlet of physical, political, and meteorological obstacles, delivering them to this point in space and time. They had just enough supplies and time for one final shot at the world’s tallest mountain—via a new route.

Heading up the Hornbein Couloir

On May 21, Hornbein and Unsoeld worked their way up the snowy defile of the Hornbein Couloir, a 45-degree gully on the mountain’s north side. They were grateful for the steps that Corbet and radio operator Al Auten, who had left two hours before, had carefully cut ahead of them.

Around 4 p.m. on May 21, they looked up to see Corbet and Auten sitting on the tiniest of ledges below a layer of light-colored, rotten sedimentary rock known as the Yellow Band. If this was the intended site for their high camp, Unsoeld worried, it had better be at least 27,000 feet. Otherwise, the next day’s climb to the summit and a timely descent might be impossible.

“Twenty-seven thousand, two hundred twenty-five feet,” Corbet sang out, reading from his altimeter as Hornbein and Unsoeld approached. Above them, the couloir narrowed and steepened. Below, the slope fell away sharply.

The Sherpas with them had completed the most demanding and technically difficult carry of the entire expedition—yet none of them had climbed to high elevations before. They constituted the scrappy handful who agreed to return to the mountain and prove themselves after the expedition had already succeeded via the South Col.

Corbet, Auten, and the Sherpas descended to Camp 4W while Hornbein and Unsoeld fixed a tent at an awkward angle, its outer 18 inches hanging over the precipitous Hornbein Couloir. They anchored the guy ropes with a piton—likely ineffectual—that they drove into the delaminating rock of the Yellow Band.

The next morning, Unsoeld’s crampons wouldn’t hold on the loose snow, and the steps he cut sent an endless cascade of sugary snow onto Hornbein. The 55- to 60-degree pitch of the couloir where it passed through the Yellow Band was relentless, offering nothing to sit on or lean against. They conserved oxygen by turning it off while securing each other with dubiously shallow ice axe belays.

Hornbein arrived at each of Unsoeld’s belay positions out of breath. He checked his regulator, which was set at a flow of two liters per minute, yet the bottle remained nearly full. A few hundred feet above their camp, the couloir narrowed gradually into a crack the width of a man’s body, forcing them to climb sideways so their oxygen bottles would fit. Then they faced a cliff 60 feet high—a long pitch of technical rock climbing. The Yellow Band’s rotten, down-sloping slabs offered few solid cracks for the placement of pitons.

Hornbein reluctantly took the lead, and he made a long step up to a steep slab with no handholds. But he was unable to make a crux move—likely affected by momentary hypoxia—so he rappelled down to Unsoeld’s stance and handed over the lead to him. Unsoeld increased his oxygen flow for improved performance and was able to surmount the cliff.

Then they reached a more manageable area of blue-gray limestone—the upper edge of the Yellow Band—at 28,000 feet. The summit was a thousand feet above them. But it was 3:30 in the afternoon, and the shadows were growing longer. They had a decision to make: Go on to the summit and complete a traverse of the mountain, or turn back. Unsoeld didn’t press Hornbein for a response; their decision had silently been made long before. And now that they couldn’t find secure rappel points, their decision was formally sanctified.

Onward to the top

Hornbein’s anxiety that they would not be able to descend by the route they came was overshadowed by a feeling of calm and pleasure at the joy of climbing. They negotiated less-than-vertical faces, flaking rock, and snow gullies, and then reconnected with the crest of the West Ridge for the first time since they had left camp the day before. Everest’s South Summit was now visible, directly across the Southwest Face. Leaning over the ridge, they peered down at Camp 2 in the Western Cwm, a mile and a half below. The wind at the crest was brisk, but the rock felt solid. They removed their crampons and climbed on the lug soles of their reindeer fur–lined boots, grateful to find handholds big enough to accommodate their mittens. For three ropelengths, they moved easily upward along the narrow ridge. Hornbein delighted in the boost he felt from being 13 pounds lighter; he had jettisoned his spent oxygen bottle.

At the top of the ridge’s rocky stretch, they reattached their crampons and continued slowly upward on wind-hardened snow. “To the north, it was a sheer drop of 10,000 feet into Tibet,” Unsoeld recounted. “And to the south, to our right, it was 7,000 vertical feet into the Western Cwm. So as we climbed, we leaned a little to the right.”

A superb sunset view

Most of the planet lay below them. Then Unsoeld raised his head—and stopped. In front of him, the Northeast Ridge and Southeast Ridge converged on a small dome of snow. Something else stood out. “Forty feet ahead was the American flag, shining in the slanting rays of the sun and flapping wildly in the breeze. It was wrapped around the picket, and frayed at the edges. It made quite an impact on our very impressionable minds,” he later said.

Tom Hornbein was following a short distance behind. “Willi… stopped, coiled the rope, and I wondered why he was standing there,” he wrote in Everest: The West Ridge. “I came climbing up and joined him and looked ahead. I kept telling myself, It can’t be the summit; it’s too near.”

With thoughts and feelings shared but unspoken, Hornbein and Unsoeld hugged. It was 6:15 p.m. Together, they walked the remaining 40 feet to the peak. “We felt the lonely beauty of the evening, the immense roaring silence of the wind, the tenuousness of our tie to all below,” wrote Hornbein. “There was a hint of fear—not for our lives, but of a vast unknown which pressed in upon us. A fleeting feeling of disappointment—that after all those dreams and questions, this was only a mountaintop—gave way to the suspicion that maybe there was something more, something beyond the three-dimensional form of the moment. If only it could be perceived.”

Sunset bathed the summits of Makalu and Lhotse and the distant high valleys in amber light, and they took photographs. Unsoeld laid a crucifix, wrapped in a silk blessing scarf given to him by Gombu, at the base of the flag. He tied another kata, this one from a Sherpa relative, to the stake. Then he said a brief prayer of gratitude for the nature of the world in which we live, and for mankind’s ability to appreciate it.

“Buddhist prayer flags and ceremonial scarf, the American flag and the cross of Christ, all perched together on top of the world—supported by an aluminum picket painted survival orange. The symbolic possibilities rendered my summit prayer more than a trifle incoherent.” Unsoeld also unfurled the pennant of the Oregon State University Mountain Club; he had met his wife, Jolene, on a club outing.

Finally, the two men spoke a few words to each other through their oxygen masks, above the roar of the wind: “Mostly an emotional expression of how close together this climb had brought us,” Unsoeld recalled. “It was a testimony to interpersonal relations, rather than to overcoming a great mountain.”

Willi Unsoeld and Tom Hornbein were only halfway home. Instead of luxuriating in the dramatic scene, or in a sense of glory, they turned to the urgent task of getting themselves off the mountain. The odds and the setting of the sun were not working in their favor. But for Hornbein, there was also a profound intuition at play.

“The prospect of descending an unknown side of the mountain in the dark,” Hornbein wrote, “caused me less anxiety than many other occasions had. I had a blind, fatalistic faith that, having succeeded in coming this far, we could not fail to get down.”

A miracle bivouac

“We saw each other, but could not see. We felt each other, but did not feel. We knew each other was safe, but we knew nothing. Man vanished into nothingness—but in that nothingness lay the strength and dignity which man’s soul is capable of.” —Lute Jerstad, at 27,450 feet on Everest’s Southeast Ridge

Hornbein and Unsoeld had reached the summit at 6:15 p.m. on May 22. While descending the Southeast Ridge—a route they had never seen—they followed what could only have been Lute Jerstad and Barry Bishop’s occasional footprints in the snow. When the sun set, only camera flash–like reflections—from distant bursts of heat lightning—remained to guide them. The beams of their flashlights dimmed to a faint glow, then offered nothing.

As they approached what they assumed was Camp 6, they heard voices. Strangely, the voices called for them to shine a light. Unsoeld triangulated the sounds, and they stumbled upon the vague outline of two people. It wasn’t Camp 6 at all—it was Jerstad and Bishop, and they were as lost as Hornbein and Unsoeld.

Jerstad and Bishop’s oxygen had run out, and they were depleted and disoriented. Hornbein and Unsoeld coerced them—and themselves—farther down the ridge. Finally halting at a relatively level patch of rock, the four men swallowed an impossible truth: They would have to stop and wait for morning.

Less than 1,500 feet below Everest’s summit—more than five vertical miles above sea level—four men simply sat down on the rocky rubble of the Southeast Ridge and curled up on their pack frames. It was 12:30 a.m., and they were dehydrated, oxygen-starved, and exhausted on one of the most exposed, wind-swept outcrops on earth. If they survived the night, it would be the highest successful bivouac in human history.

Hornbein and Unsoeld huddled together, with Jerstad and Bishop five feet above them. Hornbein untied his crampons and unlaced his boots. Instinctively, Unsoeld, known in the Tetons as the “Old Guide,” tucked Hornbein’s ice-cold feet inside his own parka, up against his belly.

The temperature dropped to –18°F, and for the remainder of the night, Bishop and Unsoeld felt no sensation in their toes or feet. Bishop focused on hyperventilating, which kept him from nodding off and losing awareness of his freezing digits. Jerstad wiggled his toes continually and was able to maintain some feeling.

Inexplicably, the breezes dwindled to a virtual standstill, leaving them in complete silence. “The night was overpoweringly empty,” Hornbein wrote. “Stars shed cold, unshimmering light. We hung suspended in a timeless void. Unsignaled, unembellished, the hours passed. I floated in a dreamlike eternity, devoid of fears, plans, or regrets. Death had no meaning. Nor, for that matter, did life.”

Base Camp was aware that four men were bivouacked high on Everest. And so was Father Moran, a Jesuit priest and ham radio operator in Kathmandu who had been monitoring the radio traffic coming from Base Camp. He prayed intently that the winds upon Everest be stilled. And they were.

The next morning, the men began to descend and were revived by oxygen carried up from Camp 6 by two saviors: Dave Dingman and Ang Dorje. When they pried off Bishop’s and Unsoeld’s boots at the high camp, they saw bone-white feet from toes to heels. They knew that once their toes thawed, the men would have to be carried. When the helicopter with Hornbein and Bishop aboard lifted off from the Sherpa village of Namche Bazaar, the team knew that the expedition, a success, had come to a close.

The legacy left by simple, strong men

The 1963 American Mt. Everest Expedition saw the convergence of 21 scientifically curious, patriotic, entrepreneurial, and visionary men. They were spontaneous and single-minded, iconoclastic and spiritual, democratic and dogmatic, employed and poverty-stricken—a cross-section of the peculiar spirit that defined America in the 1950s and 1960s. They embodied basic human values of diligence, teamwork, compromise, and compassion—the traits that carried us through the Cold War, the space race, the civil rights movement, and the assassination of JFK.

Mt. Everest would change the Americans who went to climb it. To some degree, it would also change America. Climbers and citizens were on a path of self-discovery, pushing the envelope of achievement and the boundaries of the human spirit. In 1963, Everest became America’s mountain, at least for a moment.

Big E Stats (Source: The Himalaya by the Numbers: A Statistical Analysis of Mountaineering in Nepal and the Himalaya, by Richard Salisbury and Elizabeth Hawley (himalayadatabase.com)

-

19,474 total summit attempts

-

6,206 total summits via all routes (by 3,698 people)

-

240 total deaths (top cause: falls)

-

30 summits via the North Ridge

-

7 deaths on the West Ridge

-

6 summits via Hornbein Couloir

-

5 deaths in Hornbein Couloir