Is Climbing Worth Dying For?

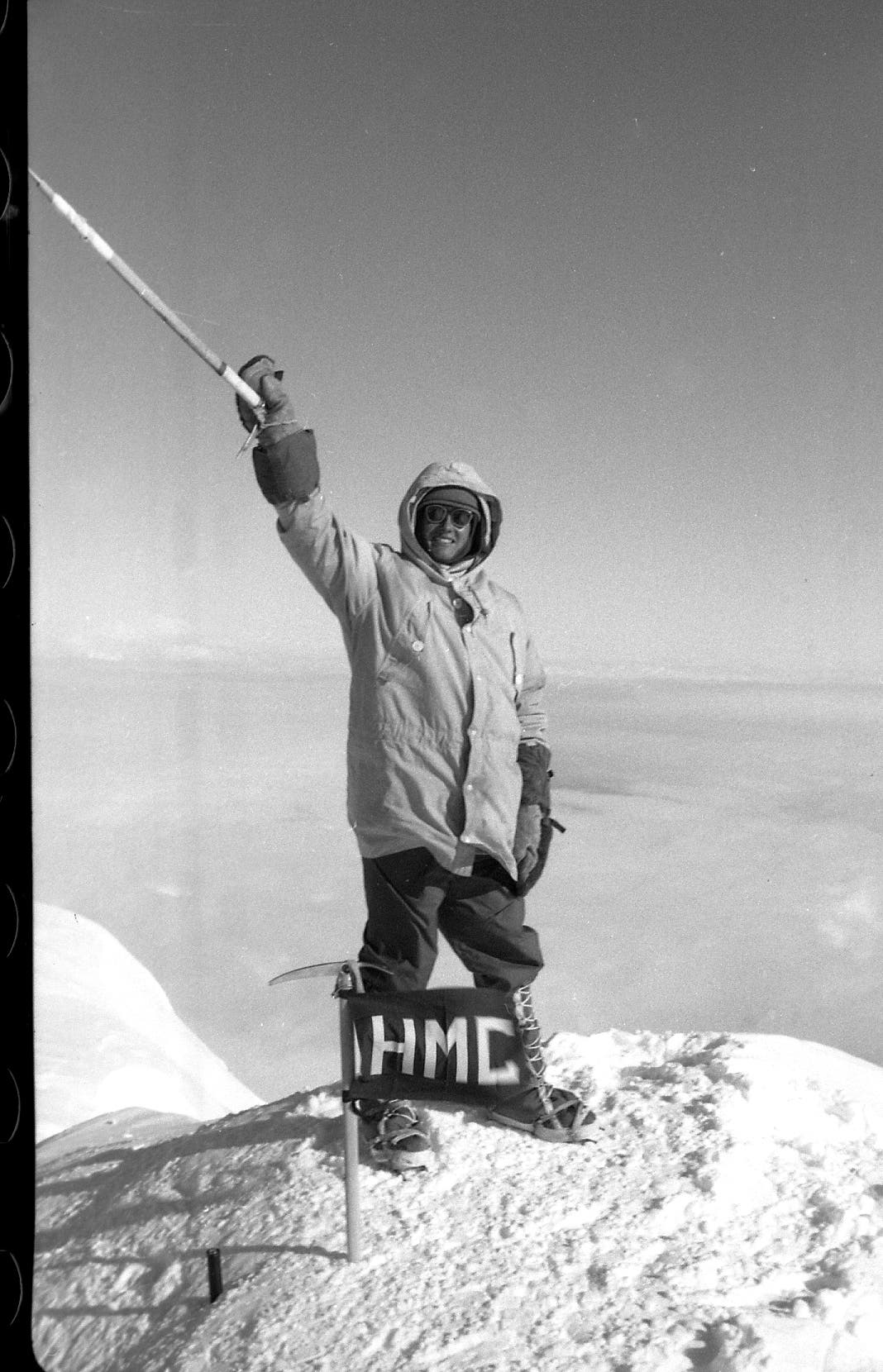

David Roberts (arms up) with Pete Carman, Hank Abrons and Riock Millikan during the first ascent of the Harvard Route on Denali's Wickersham Wall, in 1963. Photo by John Graham

In the article “Moments of Doubt,” David Roberts considers his early climbing days and the deaths of two friends. Gabe Lee fell unroped just below Roberts high on the First Flatiron outside Boulder in 1961 when Roberts had been climbing just over a year. Ed Bernd perished in 1965 after making the first ascent of the West Face of Mount Huntington, Alaska, with Roberts, Don Jensen, and Matt Hale, when a rappel anchor failed on the descent.

After the Huntington accident Roberts thought about quitting serious mountaineering. “Some of the worst moments of my life have taken place in the mountains,” wrote Roberts in “Moments of Doubt.” But, ultimately, he concluded that despite the risks and loss of friends that climbing “was worth it then.”

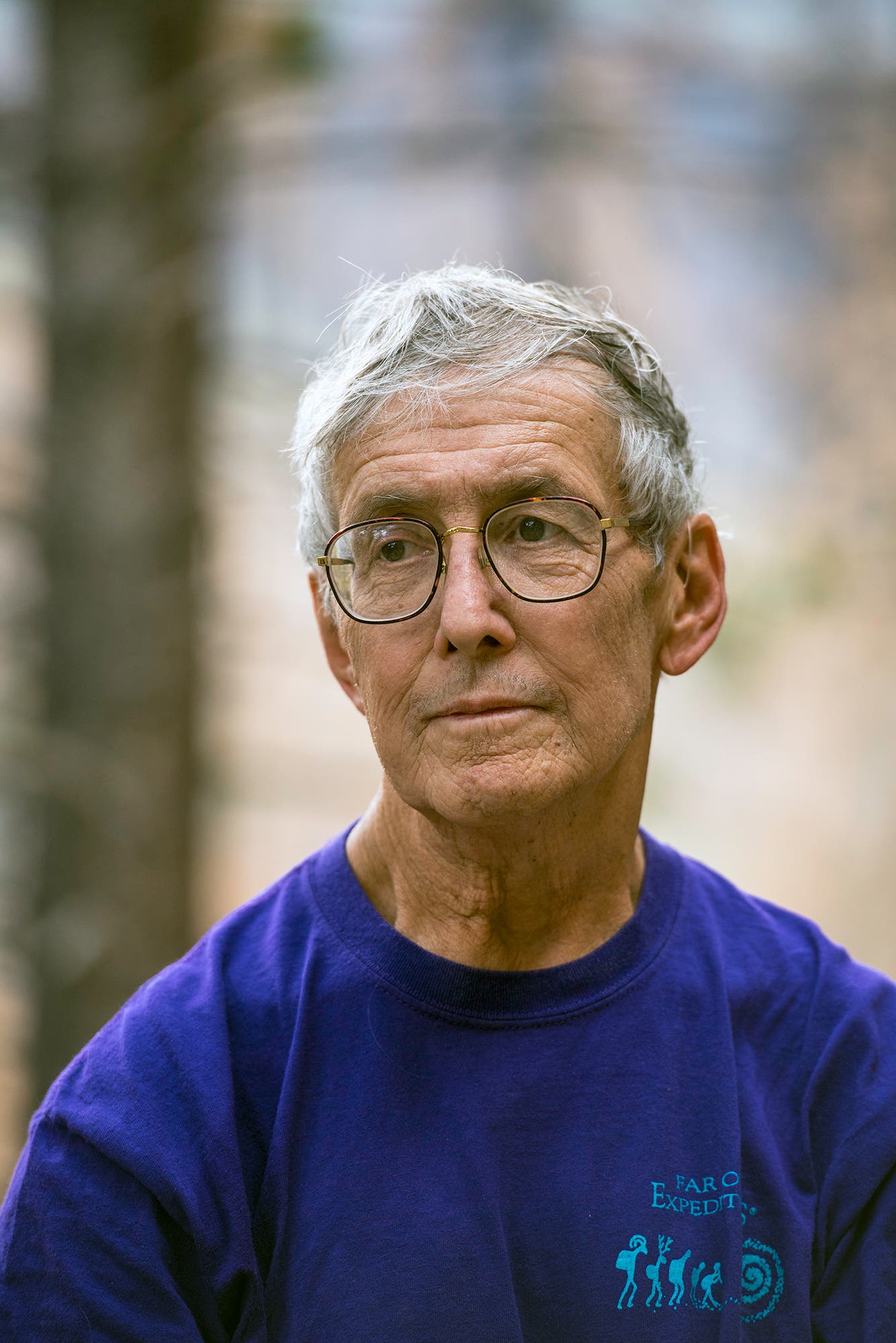

Roberts, 77 (he turns 78 in May), went on to become one of Alaska’s great climbing pioneers chalking 12 expeditions and “twenty or thirty” first ascents there including the massive Wickersham Wall on Denali in 1963, and making the first recorded visit to the Revelation Mountains, the westernmost extent of the Alaska Range. Roberts gave the untracked Revelations a name, and made numerous first ascents there.

In 1968 while working on a Ph.D in English at Denver University, Roberts wrote his first book, Mountain of My Fear, as a catharsis, a coming to terms with the death of Bernd on Huntington.

Over nine days of spring break Roberts pecked out with one finger—he never learned to type—the nine chapters of the book he would become most known for, and which is still in print.

Roberts hadn’t intended to become a writer. The son of Walter Orr Roberts, an astronomer and atmospheric physicist with a planet (and a trail near Boulder) named after him, David trained to be a mathematician, earning a BA in math from Harvard, but then thought he wanted to become a musical composer. A family friend, a composer himself, talked Roberts out of music, steering him towards writing. Roberts went on to pen hundreds of magazine articles and 32 books including Limits of the Known, where he examines our relationship with exploration and risk from his perspective of having been diagnosed with throat cancer in 2015.

Six years on, Roberts remains prolific. His latest book, The Bears Ears: A Human History of America’s Most Endangered Wilderness, landed in February.

Climbing caught up with Roberts, whose feature “Alaska Requiem,” is in this year’s edition of Ascent, to see if, over 60 years after he began climbing, whether he still thinks it is worth it.

—Duane Raleigh

What achievement, and this doesn’t have to be climbing related, are you the most proud of?

One tends to keep a special place in one’s heart (which is closer to the ego than the physicians realize) for one’s best climbs. For me: the west face of Huntington, Shot Tower, and the southeast face of Dickey. Also the coup of discovering, naming, and climbing in the Revelation Range, where we spent 52 days. Most of them in storms.

But looking back from age 77, more than 45 years after the last of those ascents, I have to give equal weight to a career spent writing, with the focus on my books, all of which were written out of love and/or passion, rather than as magazine assignments. And especially the fact that during the last six years, when I’ve been pretty sick with cancer, I’ve written four books, all four among my best.

Does climbing have a deeper purpose, does it make a meaningful contribution to humanity, or it is an activity that’s no different from any other sport?

The eternal question, which all but the most self-centered climbers agonize over. The facile rationalizations come all too easily to one’s lips: my climbs inspire others; my ventures into the unknown contribute to the great deed of discovering the “last places” on earth; by risking everything in the mountains I model a life-affirming alternative to lying on the couch and binge-watching TV.

But it’s hard not to sympathize with the absurdist label Lionel Terray chose for his brilliant memoir, awkwardly rendered in English as Conquistadors of the Useless.

The more you struggle with this pseudo-dilemma, the more it becomes meaningless. Does poetry have a deeper purpose? Does music? And how would you recognize a “meaningful contribution to humanity” if it smacked you in the face? Greta Thunberg thinks she’s making one. So did Hitler, perfecting the Aryan race.

Has climbing shaped your life? If it has, how?

Yes, of course it shaped my life. For almost 20 years, climbing was the most important thing in my life. And when I tailed off, it took years to find anything that engaged me so completely. That hiatus, during the years I was struggling to make a living as a freelance writer, brought with it an underlying anomie, a dull, constant thrum of purposelessness.

I’ve often said that finally, at about the age of 50, I discovered the remedy, in an interest that grew to obsession with the Ancient Ones of the American Southwest—Anasazi, Mogollon, Fremont, and their kin—who left behind the most stunning ruins and rock art panels in the United States. I’ve written six books about those vanished Old Ones, and I like to claim that this new passion is less self-involved than my old one: searching for prehistoric sites in remote canyons is not about me, it’s about them: about the how and why of the civilization they built and abandoned just before 1300 AD.

Yet I wonder. The quest to understand the Ancients is not one I’d willingly give up my life for. The quest for a summit was. Youthful obsession is fanatic, and it holds life cheap. But in one’s later years, there’s nothing quite so deeply involving.

What was your greatest fear, was it of being injured or killed climbing, of the unknown, situations or conditions beyond your control or something else?

Oddly enough, my greatest fear was never of getting killed, but of failure. Of chickening out where others would have gone on, and of not knowing how to weigh the difference. That said, like all climbers, I had the bejeesus scared out of me too often by close calls, and in the grimmest predicaments I made the age-old pledge to myself, If I get out of this alive, I’ll never go climbing again. But once you traverse to safety, that pledge evaporates, and all you taste is hunger for the next great challenge.

Is climbing, alpinism in particular, worth the risk?

The fundamental question. In 1980, in my first piece for Outside, I asked myself that question, framing it as an attempt to explain why, having witnessed the fatal falls of my partners Gabe Lee when we were both 18 and Ed Bernd when he was 20 and I was 22, I kept climbing for many more years. I actually titled the essay “Worth the Risk,” but editor John Rasmus gave it the better title of “Moments of Doubt.” I answered my own question with a resounding “Yes.” (That essay is still my most anthologized piece.)

But 25 years later, in my climbing memoir On the Ridge between Life and Death, I came to a quite different answer, a highly qualified “Maybe.” It took me all those years to realize that in 1980 I had faced the query, “Is it worth the risk?,” only in terms of myself. The “yes” boiled down to a calculation that the joys of climbing outweighed the sorrows.

What I hadn’t pondered was the lasting impact of a climbing death on the victim’s loved ones. In 2004, I looked up Gabe’s brother and sister, whom I hadn’t seen since 1961. Marian, in particular, had nursed a 44-year rage against me, fueled by her incomprehension of what had gone wrong that July day on the First Flatiron.

By the end of our marathon encounter and the writing of my book, I was reduced to that tentative “Maybe.” And that’s the conclusion I stick with today.

What is climbing’s single biggest change since your early days of climbing?

The incalculably profound change, and to my mind, the younger generation’s great loss, is how connectivity in all its guises—from airplane and helicopter rescue to sat phones and inReach devices and the GPS and Internet—have redefined the game. Seldom these days does a climber go off with the mantra in his head, If we get in trouble, it’s up to me and my buddies to get us out. Instead, you can hop on the phone/beacon/support-team link and sit and wait to be rescued.

If you were younger today, say 15 years old, would you become a climber and if you would, which discipline would you prefer?

I often think I’d be drawn to caving rather than climbing. Right now, caving is in the middle of a “golden age” not unlike mountaineering’s in the 1950s. The Everest of caving—the deepest pit in the surface of the earth—not only has yet to be fully plumbed: it probably hasn’t even been discovered. I’ve been in only a couple of serious caves, guided by experts. But their zeal and sense of brotherhood remind me, for instance, of the scene at the Gunks in the early 1960s.

They’re all nerds, and they dress in Army-surplus overalls and sweatshirts, but we were nerds back then. They’re not competing for new lines five or 10 feet left or right of existing routes, but for tubes and shafts and amphitheaters no one has ever seen before, spangled with fragile, unworldly “speleothems.” Those cavers exude wonder. How much wonder do you run into nowadays at Rumney or the Red or Eldorado?

When did you stop climbing seriously and why?

Like most climbers, I didn’t abruptly quit; instead I just gradually tailed off. At the age of 35, I started to think that I’d been pretty damned lucky to survive my close calls, and that I wasn’t likely to get any better at climbing in the coming decades. And life began to seem richer, if more ambiguous, than my fanatic pursuit for unclimbed mountains and new routes. It took quite a while, though, to find another quest that engaged me half so profoundly. (See above, under the Ancient Ones of the Southwest.)

What do you know now that you wish you’d known when you were you were at you climbing prime?

That life is too precious to throw away. That love and friendship are more important than achievement. That the only planet we’ll ever inhabit, no matter how humans try to destroy and pollute it, is inexpressibly wonderful, and leaving it—for those of us who put no stock in the old fairy tales of Heaven and an afterlife—will be the hardest thing we’ve ever done.