Making Bargains With God on Mount Logan

"Mount Logan Ridge"

Liam Suckling, 27

Melbourne, Australia

Every mountain has a story to tell and lessons to impart. The ruthless ice fields of the St. Elias range and its crown jewel, 19,551-foot Mount Logan, would teach me something about boundaries.

At 11,400 feet, pain pierced every extremity. Within minutes, I had gone from lucid cognition and physical fluidity to burning muscle spasms and a mental maelstrom. One moment I had been focused in full swing, pushing my own limits and leading up two pitches of bottomless, steep, sugary snow, and now I was breathing fire in an inverted world beyond a darker and more mysterious boundary.

The turbulence escalated. A ripple of agony curled my toes up, and I collapsed onto my anchor. I couldn’t speak coherently. I was disintegrating.

I felt a deep frustration with myself for holding the team up, but I couldn’t make sense of the scene. I’d felt great climbing at almost twice this altitude in the past. I was well-hydrated. Why was the machine of my body failing me at such a crucial moment? Later I would learn that my symptoms came from too much carbon monoxide exposure due to cooking in the tent without enough ventilation, combined with rapid-onset altitude sickness. I’d pushed beyond the limits of my physiology for the speed at which we were gaining altitude.

Matt, Noah, and Jason gathered near me and commenced organizing a rescue plan; their mental dexterity was mesmerizing to me. Guilt and frustration stabbed again. I knew of being the rescuer but not of being rescued; it was agonizing to accept. I felt like I was floating, and rather than having thoughts, I was somehow watching those thoughts from afar with decreasing conviction that they were somehow related to me.

“Keep moving, man,” I could hear Jason’s voice and feel the axe in my hand plunging into the slushy snow. We were descending to meet the chopper that would take me in for evaluation. The familiar human limitations eventually returned, though I remained less convinced of how strict those boundaries are.

Jason Mari, 28

Humble, Texas

It started at 11,000 feet as a little discomfort. At 12,000 feet, it felt like someone was standing on my chest. At 14,000 feet, the gurgling started. If I fell asleep, I would immediately wake up in terror to the sensation of drowning, so I didn’t sleep. I was suffering from HAPE (high-altitude pulmonary edema), a condition that causes a climber’s lungs to fill with fluid. The only treatment is to descend to a lower elevation.

Three days later, having summited Mount Logan and started the descent toward the King’s Trench Route, we were pinned by a storm. In my tent, the only consolation was being sheltered from the storm that was raging outside. At night, the winds picked up, and the temperature dropped to -40°F. During the day, the storm continued, and in our desperation, we tried to move our camp in the whiteout. We might have made it a few hundred feet across the glacier.

My promise to my partners was that I would keep going until I dropped. Their promise to me was that if I did, they would drag my lifeless body home. I have always taken pride in being tough. Not the strongest or fastest or smartest, but tough. That can count for a lot. But near the summit plateau, I broke down completely, realizing that I might be a liability for the team. This experience would forever change my perception of myself, mountaineering, and what a team is capable of.

Mount Logan kills by a variety of ways, most often by turning down the thermostat. Temperatures below -100°F have been recorded on this plateau. For that matter, a two-week storm could blow in without warning.

Over the course of those tent-bound days, I had a lot of time to think. I didn’t question our decision-making, as I believed we were correct in the moment (and still do in hindsight). But I did wonder about our fate. Every extra minute we spent on the summit plateau worsened our chances of survival. Mount Logan kills by a variety of ways, most often by turning down the thermostat. Temperatures below -100°F have been recorded on this plateau. For that matter, a two-week storm could blow in without warning. For obvious reasons, we would have a hard time surviving either event. The possibility of death lingered constantly, and it enraged me. My thoughts continually wandered back to my family and friends at home. My responsibility for the people I love and specifically thinking of a letter my sister wrote to me before the trip were the fuel that drove me up the final 1,000 feet to gain Prospector’s Col and our eventual exit from this peak.

In our final moments on the plateau, my physical condition deteriorated substantially. Each weak step required two of the most painful, shallow breaths that my lungs could bear, after which I proceeded to gasp for air in between fits of coughing, weighting my single, broken trekking pole. For what seemed like an eternity, I alternated crying tears of despair and throwing fits of rage. My mind was host to a circus of emotions. Each time I felt like giving up, I was overcome by a fury that I cannot understand or really explain. It pushed me through the descent and ultimately led to my survival.

Noah McKelvin, 22

Denver, Colorado

Mount Logan is not of this Earth. So remote, harsh, and endless. It’s a place where time doesn’t exist.

During the two-day storm we weathered near 12,000 feet, I listened to my stomach grumble and stared at our food, nervously anticipating the moment we’d run out. We’d planned for a week-long climb, and I questioned every step that got us here. I knew how easily these tent-bound days could turn to weeks. How much snow could we melt with our meager fuel supply? A dark mood descended over us.

I prayed to God. For me, the thought of dying without having felt that I truly gave life everything I had scared me. I told God that if I made it out, I would use my second chance to care for others more than myself, never to waste a moment of life, to push myself as a climber and as a human being.

My past became a dream, and the future was uncertain. There was simply this mountain and nothing else. The moment I tried to take comfort in what life was like back home was the moment I lost concentration.

The whiteout soon turned into a bone-chilling cold snap, and I felt we needed to move or we risked never getting out alive. The views at night were something from a dream: infinite snow and ice, the silence deafening. I set off on a steeper pitch of ice, soon encountering snow-covered mixed slabs. I hammered in one picket and belayed. I was exhausted, weighed down, crouching with my head on the snow. There was only onward. Snow conditions were dangerous enough that descending would’ve been a nightmare. The rope so frozen, we soon started hip belaying. We made it to a wide, flat spot with a sea of clouds below.

Mount Logan was holding on to us with an unexplainable grip, we held on to each other even stronger. This changed us forever.

Gaining ground boosted our spirits ever so slightly. We had to give it everything we had. Every day we moved, we did so until we could not take another step forward. My body tried to find the strength somewhere as it slowly ate away 15 pounds of itself over the course of only 15 days. Pulmonary edema was becoming a horrifying reality for Jason, but we thought of every step forward as a step to safety.

Though Mount Logan was holding on to us with an unexplainable grip, we held on to each other even stronger. This changed us forever. My old self died on that climb, and I was reborn with a new respect for life. Ultimately, I think that’s exactly why we climb and what we went for.

Matt Grabina, 28

Boulder, Colorado

There would be no point in delaying. We had already traveled far beyond our comfort zone. At home in Colorado, I would never have dreamt of stepping onto such a slope, but here, little choice remained.

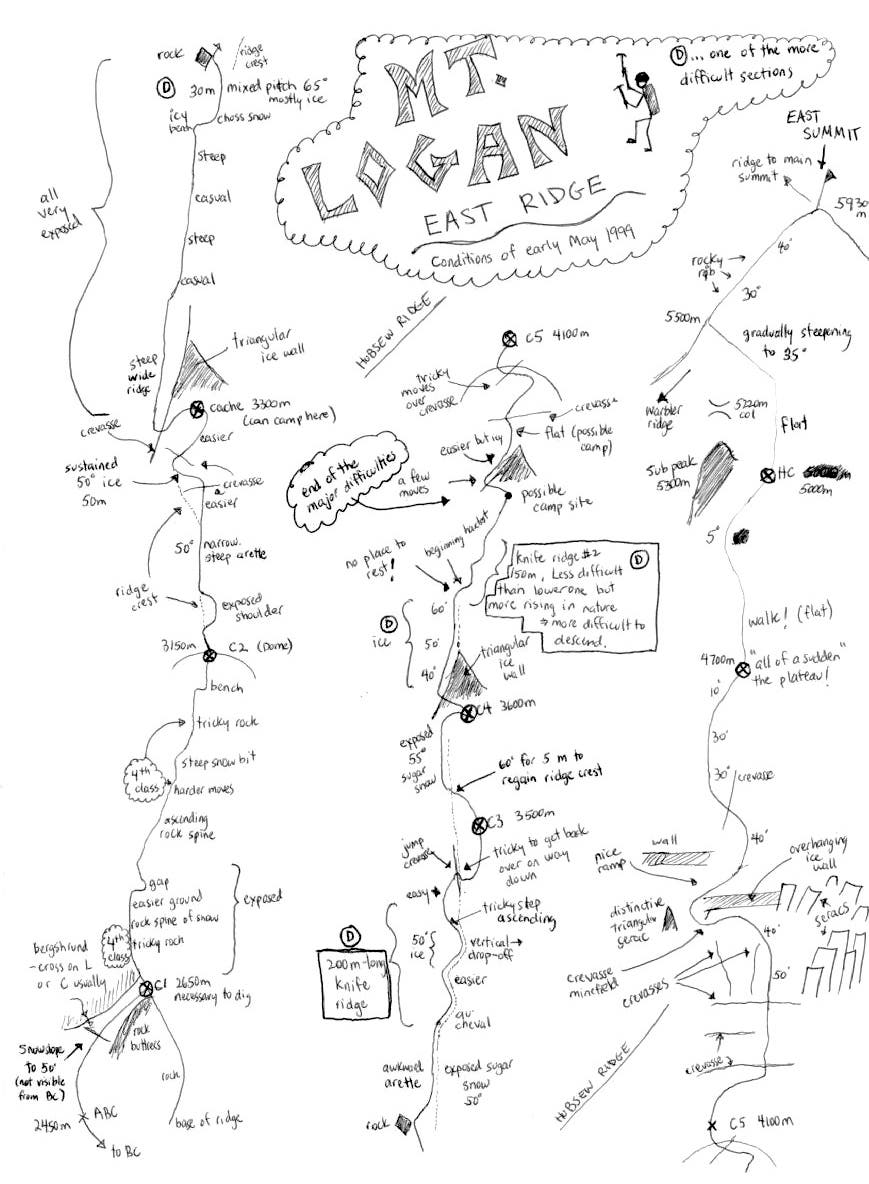

The handwritten route beta (below) suggested we had reached the “end of the major difficulties,” but this information was 15 years old, so who knows. What we did know was that the climbing wouldn’t be technically difficult but deep powder promised an aerobic workout and heightened fear given the avalanche danger. And damn, was it painfully cold! The darkest hours of the Yukon night are simply too icy to get any quality rest, so we planned to move again just to keep warm.

The bit of comfort the team had taken in reaching the end of those technical cruxes faded as we faced off with a danger we had little control over. This slope could rip at any moment. Here we traded in run-of-the-mill fear for terror in the face of a truly objective danger. We moved slowly, fighting for every step.

We found ourselves outside of time, unsure of what our future held. I found it best to set aside fear of what I could not control, with hopes of making room for courage or anything else to take its place. Soon enough, the going became safer and easier, and the sun was up. When we reached Camp 8, it was difficult to recall how cold and bleak things had been just hours before.

An expedition is full of highs and lows. This one gave us the lowest I’ve ever felt, but I knew in that moment that the lows forced us to climb on and live life for all it could offer. But looking out over the ice fields and countless summits, each begging for adventure, I felt only the highs.

Mount Logan Climb Timeline

By Noah McKelvin

In total, we were in the Great White North for more than 45 days. We bought an old van in Anchorage and drove to British Columbia to charter a bush plane into the St. Elias range with our sights on Mount Logan, Canada’s highest peak—and the biggest chunk of ice and rock on the planet. It’s remote and notorious for foul weather, so few attempt it. Some years, only a couple people (literally) reach the summit. Inauspiciously, the van broke down a few times on the way. We were on the glacier for 21 days, and upon hearing we had a seven-day weather window, we went for it. We were on the East Ridge of Mount Logan for 15 days.

6/1 Started up East Ridge and climbed through the night (with a two-hour sitting bivy).

6/2 Arrive at Camp 1 (9,500 feet). Storms a little that afternoon.

6/3 Move to Camp 2 (10,800 feet).

6/4 Attempt knife-edge crux, get shut down by midday heat causing unstable conditions.

6/5 Rest.

6/6 Move over crux and reach Camp 3 (11,975 feet). Liam evacuated that afternoon.

6/7 Tent-bound in whiteout.

6/8 Tent-bound in whiteout.

6/9 Leave camp in evening and climb overnight to Camp 4 (13,943 feet).

6/10 Rest.

6/11 Gain the plateau; Bivy at Camp 5 (17,600 feet).

6/12 Traverse east and main summits to camp 6 (17,550 feet).

6/13 bad Weather. Attempt to move camp, make it a few hundred feet.

6/14 Descend to King’s Trench and Camp 8 (13,451 feet).

6/15 descend remaining route and fly out! An 11-day storm hits 12 hours after our departure.