The Unlikely Rise of a Climbing Hero

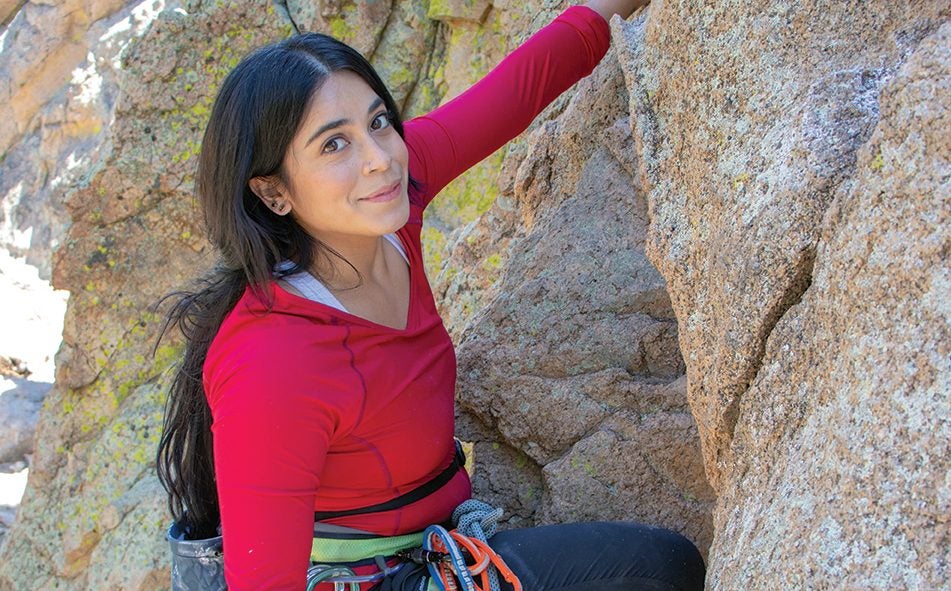

eady on Claim Jumper (5.10a), Holcomb Valley, Southern California, in 2019. (Photo: Antonio Ayala)

This article first appeared in Rock and Ice.

On a starless spring night in 1999, a 9-year-old girl opened her window, popped the screen, and swung her legs out. Brushing against the siding, she watched large flakes of peeling paint fall 15 feet to the ground. “This is it,” she muttered. “Now or never.”

Diagnosed with scoliosis two years prior, Maricela “Marci” Rosales had been periodically bedridden. While a back brace hindered her mobility, it was not the greatest limitation to her exploration. Since their neighborhood bordered Los Angeles’s housing projects, where drugs, gangs and stray bullets posed ever-present dangers, Marci’s parents enforced strict rules about when she could leave the two-bedroom unit they shared with Marci, her brother, her sister, a nephew and a great uncle.

The moldy, dilapidated structure that sheltered Marci felt like her prison at times; the brace that supported her back, her shackle. She found solace thumbing through second-hand copies of National Geographic her father had bought for pennies at estate sales. Losing herself in images of faraway lands, Marci longed to see the world from all its angles.

From her windowsill perspective, Marci surveyed the landscape: the neighbor’s old trailer and a skeleton of a garage, charred black from a long-ago fire, loomed across the driveway. Just then, a distant shot rang out, and like a runner at the starting line, she was off. Marci manteled out and stemmed between the roof, the wall and a tree to land below her window.

“Nature was something reserved for people with means … not for brown girls in the inner city,” Rosales says.

As she ran across the tiny patch of grass adjoining the house, Marci imagined having just descended a mountain, and traversing an alpine meadow like the adventurers she had seen smiling on the magazine pages. As quickly as she escaped, though, Marci was yanked back by her father.

“I don’t know how he knew,” says Rosales, now 30, “but he always caught me doing things I wasn’t supposed to.”

The stunt earned her a spanking, but Marci knew her father was just glad she was safe. The adventure seemed worth it, but something else became clear: Marci’s reality had no mountains or meadows intertwined with wispy fog. It was concrete and freeways choked by smog.

Also read: Why Aren’t There More Black Climbers?

“Nature was something reserved for people with means … not for brown girls in the inner city,” Rosales says. “The idea that people actually climb to the top of mountains fascinated me, but it was so far outside my reality … I just forgot about it.”

Kenji Haroutunian, director of California Outdoor Recreation Partners, who has mentored Rosales since 2015, marvels that she managed to find rock climbing. “Her background meant the odds were stacked against her before she got out of the gate,” he says.

Beyond the lack of economic resources, Marci faced another major obstacle. While outdoor recreation by Latinx is at an all-time high, based on data from the 2019 Outdoor Participation Survey, it was historically not part of the culture. No data existed for the 1990s, when Rosales was a child, but just 24 percent of Latinx responded that they participated in some form of outdoor recreation in 2010, compared to 44 percent today. The lack of participation is particularly dramatic in first-generation Latinx populations.

In the Puerto Rican culture in which Marci was raised, the barrier is especially high for women.

“We didn’t know people who climb rocks,” says Gladys Rosales, Marci’s mother. “I get my daughter like to go outside … She is, how do you say, terca [stubborn]. In our culture, wilderness is for men. Women belong at home, away from danger.”

Add scoliosis to the mix and the obstacles to climbing seem almost insurmountable. The severity of her condition and the lack of access to proper treatment left Rosales struggling with basic activities. When talking about her scoliosis, she still grimaces. “My bones felt like they were coming out of my skin,” she says. “There were days the pain was so intense I couldn’t get out of bed, I couldn’t go to school, so doing sports was impossible.”

Despite missing school, and her father’s cancer diagnosis during her junior year of high school, Marci kept her grades up. Intent on an education, she applied for grants and took out loans to enroll at the University of California, Riverside (UCR) after graduating from high school in 2007.

Yet at UCR she grappled with social integration as well as the rigor of college academics while trying to maintain connections to her family and fiancé back home. After the end of her first quarter, she and her fiancé ended their half-decade relationship. The resulting void sent Rosales into a maze of doubt, but also gave her space to explore the person she wanted to be.

In the spring of 2008, a dorm mate invited Rosales to try out the school’s climbing wall. At age 18, she was 5-foot-2 and over 200 pounds, but Rosales accepted because she wanted to be more social and try new things.

Looking up at the wall, she thought, “Wow, I’m supposed to get up there?” Still, she tried, which impressed Adaly Soriano, a high-school friend who joined the group at the wall.

“Marci didn’t get very far off the ground,” says Soriano. “It’s not only that she was out of shape, but there was a lot going on. Her father was dying, her mother was already dealing with health problems, and things fell apart with her fiancé.”

Rosales says that after her first attempt at climbing, she was neither disappointed nor discouraged. “I actually had no feelings one way or the other about it. [Climbing] was just another thing I couldn’t do,” she says.

In her sophomore year, Rosales was unable to afford housing: Her only viable option was living in her car. “I mean, I barely had a car—my little Scion was definitely a lemon. I could have died in that thing,” she says with a chuckle. Knowing that she was not the only homeless college student kept her from being swallowed up by a sense of shame, but sleeping in a confined space exacerbated her scoliosis, and her health continued to deteriorate. Rosales guesses she tipped the scales at 220 pounds, but could not be certain because she had stopped weighing herself long before that point.

To manage her increasing physical pain and emotional distress, Rosales found relief in Vicodin and other prescription painkillers. “It was a really dark period in my life, and I’m not proud of it,” she says. “I was addicted, and in a constant drug fog, but I didn’t know how else to cope.”

In an alternate universe, Rosales might have become an opioid statistic, but as nearly everyone who knows her can attest: She is tenacious, a self-professed fighter. She refused to let her circumstances define her story.

“I knew I couldn’t wallow in my problems,” she says. “My father was sick, and my family needed me, and I wanted to get strong for them.”

In her junior year at UCR, Rosales decided the first step to getting healthy was to strive for better fitness. She focused on the school’s Student Recreation Center by diligently monitoring its online jobs portal, and by the end of spring semester in 2010 found work as a facilitator at the challenge course.

The job put Rosales into the middle of the action. After her shift she often stopped at the climbing wall, where she was mesmerized by the athletic bodies contorting in impossible ways. She tried climbing again over the summer break, when many students left campus, so few would be around to see her fail.

“I couldn’t imagine how I would ever become a real climber … with my squatty, lopsided frame … but I climbed anyway,” she says. Rosales couldn’t finish even the easiest routes, but continued to return and got farther each day.

Two experienced climbers, Mary Becraft and Ian McGarraugh, observed her determination as Rosales worked out the intricacies of climbing and learned how to leverage her body—drawing from a love of dancing central to her Latin roots. Becraft and McGarraugh began giving Rosales climbing tips, at first cautiously, but soon invited her into their circle of half a dozen climbing friends.

“We all wanted to see Marci succeed,” Becraft says.

“Everyone gave her pointers and rallied her to try again after falling,” says McGarraugh.

The community of climbers at UCR propelled Rosales beyond the indoor walls, but she was woefully unprepared for her first outdoor climbing excursion. During winter break of 2010, the UCR rock-climbing club loosely organized a trip to Bishop. There was limited information and no gear checklist. All Rosales knew was that she needed climbing shoes, a tent, a sleeping bag, and warm clothes. She found a pair of ill-fitting shoes, and at the last minute, her father managed to purchase an oversized thrift-store ski jacket. Rosales had never spent a night outside, didn’t know how to pitch a tent, and had no idea she needed a sleeping pad to insulate her from the frozen ground. Despite waking up cold to the core, she was blown away by the Buttermilks. The sun rising over enormous granite boulders strewn about the high desert valley, surrounded by the distant peaks of the Eastern Sierra, stunned her.

“This was the first time I actually experienced nature in a different place,” Rosales says. “I’m from the city.” She had seen the desert landscape of Riverside, but it was an urban environment.

“Bishop was a small town. I’d never seen a small town before. And going into the Buttermilks, and going down the dirt road, and then just seeing these boulders … and then the Eastern Sierra. I’ve never seen that, and they were all snowcapped, and there’s snow everywhere … I was like, Whoa.”

Even today Rosales tears up when she talks about it. “It’s almost like a religious experience … or maybe a spiritual awakening … Everything about that trip—the blue sky, the crisp air, the feeling of warm gritty rock under my fingers—was so AMAZING! I was hooked.”

In the subsequent months, Rosales’s desire to get healthy and her newfound love for outdoor climbing forced her to formulate a plan to break her cycle of drug use and focus on a holistic approach to pain management. After extensive research, she found a chiropractor who helped address her spine misalignment, and she began physical therapy.

Her body and mind adapted …. Her pain decreased dramatically and was replaced by the joy of climbing.

“I was very lucky to be able to access affordable health insurance through the school,” says Rosales, “and I was able to find [a doctor] who listened to what I needed and helped me get away from [my] dependency on pain meds … in about four months.”

More than anything, Rosales immersed herself in climbing and leaned into its transformative power. “I became obsessed with climbing for the next five years … and in so many ways, it saved me,” she says. “I gained strength, found ways to cope with problems, and was inspired to finish school.”

Climbing taught Rosales patience. She tackled each wall she encountered one hold at a time, whether in the gym or out at her favorite crags. She kept trying, she says, “to do better than the time before.”

In less than a year, Rosales began ticking off routes she had never dreamed possible, and her body and mind adapted to the demands of the sport. Her pain decreased dramatically and was replaced by the joy of climbing. By 2013, Rosales was climbing 5.11s and projecting 5.12s— unrecognizable from a time when she couldn’t climb anything. She ditched her back brace, stopped prescription painkillers, and slimmed down to about half of her peak weight.

Yet despite her increasing amount of time on the wall, the more challenging projects, and the countless climbing trips to Horse Flats, Holcomb Valley, Echo Peak, Malibu Creek, Big Rock, Tramway, Joshua Tree, Red Rocks and Bishop, one thing kept Rosales from embracing her identity as a climber: her family’s disapproval.

“When I first told them about climbing rocks, my mother nearly passed out, and my father started screaming,” she says. “All he saw was me putting myself in harm’s way after all they had done to protect me.”

For years, whenever Rosales mentioned climbing, her father would simply dismiss it with, “¡Es para locos!” (“It’s for crazies.”)

“I tried to brush it off … and learned to live with the disapproval, but it really hurt,” she says.

A few months before his death, in 2012, Rosales’s father accompanied her to the Mad Rock retail outlet in Santa Fe Spring as she geared up for bouldering season. Looking at the gear and flipping through issues of Rock and Ice, Marco Antonio Rosales finally understood that rock climbing was a bonafide sport that underpinned an entire industry. For the first time he recognized the positive impact climbing had had on his daughter, who had evolved, without him quite noticing, into a happy, vibrant and pain-free young woman. Shortly before his passing, Rosales’ father gave his blessing: “Tu escalando ha sido lo mas feliz que habia visto en tu vida. Por favor no dejes tus pasiones.” (“When you climb, it is the happiest I’ve seen you. Please don’t give up your passions.”)

She navigated around pockets of drugs, gangs and stray bullets to talk to at-risk youths about her experience as a child of an immigrant, a climber and the first in her family to finish college.

“His blessing was the missing piece I needed,” she says. Her voice cracks.

Her father’s death dealt a new blow to Rosales, and a fall when someone accidentally pushed her down a flight of stairs landed her in a wheelchair.

“It felt like, ‘I can’t win,’” she says. “It was hard to deal with the loss of my best friend, my father … and it was hard to stay positive … but the support of the climbing community got me through.”

To pull her out of her funk, friends invited Rosales to the crag as soon as it was practical. “It was another low point in life, but in so many ways it was also a high because I was taken care of by an amazing climbing community,” says Rosales. “My friends would not only get me outside, but also remind me to bring my homework, and remind me to stay focused on my goal” of graduating.

Rosales took her lessons from climbing and applied the same patience, focus and discipline to her academics, where she had previously bounced in and out of probation. In 2013, she graduated from the University of California, Riverside, with a bachelor in Sociology and Law & Society, a milestone she celebrated with a climbing trip to the Tramway in the San Jacinto Mountains.

Beyond academics, rock climbing also opened doors into the outdoor industry.

A few months before graduation, Rosales had a chance meeting at the local climbing gym with Kenny Suh, who leads sales and marketing at Mad Rock. After learning her background, Suh offered her a position on his sales staff, and made her a brand ambassador.

“As a minority-owned company, our approach to our climbing-team ambassadors has always been unconventional,” says Suh. “We didn’t want to just focus on people who are at the edge of climbing grades.

“Marci wasn’t a 5.15 climber, but she was committed to advocating for climbers of all walks. With her subsequent connection to Latino Outdoors, it turned out to also be a positive step in engaging a growing but under-represented community.”

Rosales’s Mad Rock ambassadorship let her add her voice to the climbing community at large. “I never hesitate reaching out to people to offer pointers, and use my story to show how accessible rock climbing can be,” she says. “For people who are intimidated by climbing like I used to be, it could mean the difference between giving up and trying harder.”

Driven by her love of climbing, Rosales has made public-lands access and advocacy her mission. In 2014 she got involved with Los Angeles Wilderness Training (LAWT), which provided outdoor-skills training for adults who work with inner-city youths. That led to work with Latino Outdoors (LO), a non-profit that connects the Latinx communities to outdoor recreation.

She also returned to central Los Angeles to volunteer with the StepUp Women’s Network after-school program. Every Thursday for a year, she navigated around pockets of drugs, gangs and stray bullets to talk to at-risk youths about her experience as a child of an immigrant, a climber and the first in her family to finish college. She encouraged young people of color “to look beyond the streets, and find opportunities to explore the outdoors.”

Rosales has participated in countless advocacy, stewardship and diversity initiatives ranging from disability access on public lands with the Disability Rights Legal Center to Spanish-language educational initiatives with the Access Fund. In 2018 and 2019, she represented California at Climb the Hill in Washington, D.C., to lobby for climbing access.

Rosales’s dedication to causes had a price: Much of her work was unpaid, and she lived in her car on and off until this year.

Rosales jokes that living out of a Subaru Outback was an upgrade from the Scion, but says, “Of course I wanted more. I wanted a place of my own, but L.A. is expensive.”

In 2019, Touchstone put Rosales in one of its head-coach positions, but she still couldn’t make ends meet, and stayed in the gym’s parking lot when L.A. banned sleeping in cars on public property.

The pieces started to come together in 2020 when Rosales became the California program associate director for the Conservation Land Foundation, where, among other duties, she works with marginalized communities to become better advocates for public lands.

“We wanted somebody who is passionate about public lands and has a commitment to equity and diversity,” says Elyane Stefanick, one of the California program directors. “Marci was the perfect fit.”

Charlie Lieu has spent the last quarter of a century climbing on all six non-frozen continents. She lives in Edmonds, Washington.