Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

The boulder fields above the basecamp of India’s 22,520-foot Changabang are an unforgiving place. With 60 mph winds and subfreezing temps at 14,000 feet above sea level, it’s a harsh environment. But Jamie Logan saw it as a refuge. In the days leading up to an attempt on the summit in 1979, Logan wore a tie-dyed cotton skirt she’d bought in the market in New Delhi. Wandering around alone in the skirt offered her the freedom to wear women’s clothes without judgment. It was a desire she’d had at least since her teens, though she had no idea why. Dressing like this made Logan feel more like herself.

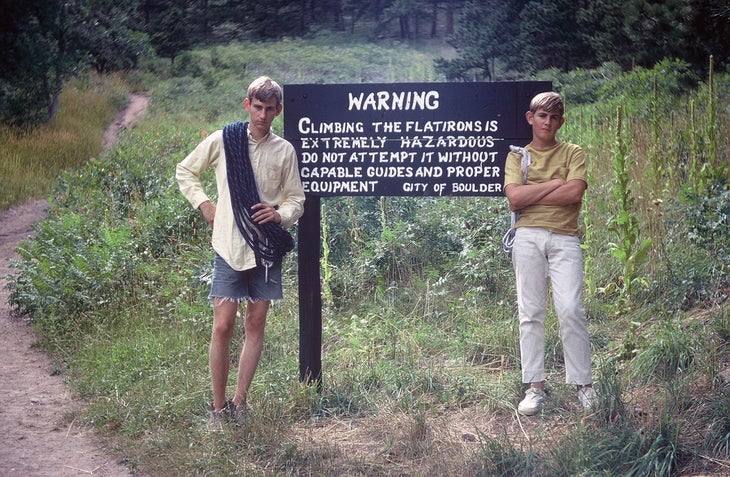

If you don’t know who Logan is, the short answer is: one of the great pioneers in North American free climbing. Today, Logan, age 70, is a successful architect in Boulder, Colorado, with a small firm that specializes in energy-responsible design and structures with low carbon emissions. But in 1965, Logan was just another kid who’d come to Boulder ostensibly to attend the University of Colorado, but ended up climbing so much that she flunked out in her freshman year. From then on, she began to make her mark. In 1966 when she was 18 years old, Logan and partner Chris Fredericks made the first free ascent of Crack of Fear, an infamous three-pitch 5.10d offwidth that Royal Robbins and Layton Kor, among other strong climbers, failed to free. In 1976, Logan and longtime climbing partner Wayne Goss made the first free ascent of the Diamond of Longs Peak by linking D7 into the Forrest Finish into the Black Dagger Chimney, with the crux pitch clocking in at 5.11b/c. In 1978, Logan and Mugs Stump made the first ascent of the shale-covered Emperor Face of Mt. Robson (12,989 feet) in the Canadian Rockies. It took Logan six hours to lead the 150-foot crux pitch, with a bamboo axe and a Forrest ice hammer. When Steve House repeated the pitch 30 years later, he called it M8.

But perhaps Logan’s boldest move has been transitioning to life as a woman. In a small town like Boulder, Colorado, she has experienced both freedom and exile by finally living the life she wants. Transitioning was not an easy decision, one Logan has called “way scarier than the Emperor Face.”

But back to Changabang: Having spent all 30 years of her life trying to hide her secret, Logan found a welcome peace in those boulders. But intense fear punctuated that quiet. She was scared of the unknown, of the thousands of feet of rock, ice, and mixed climbing on their objective: the Japanese Route on the Southwest Ridge, first climbed in 1976. She was scared of the fast-changing conditions that could wipe her and her partner Dakers Gowans off the face of the earth in seconds. But most of all, Logan was scared that someone would see her wearing a skirt.

At age 11, Jamie Logan went climbing with family friends, WWII veterans from the Tenth Mountain Division. They took Logan climbing in the Davis Mountains near her home in Midland, Texas. With a WWII hammer, pitons, and a rope tied around her waist, Logan led her first pitch when the soldiers couldn’t do it. Growing up as the oldest of four brothers, Logan never had a girlfriend or much experience with women, other than her mother. “I never knew how to be around women and girls,” she says. “I was befuddled by the whole thing.”

Logan had always wanted to climb everything—rocks, trees, buildings—so when she boarded at the Fountain Valley School in Colorado Springs, she organized a rock-climbing club. A few years later at the University of Colorado in Boulder, she started climbing in Boulder Canyon, putting up routes with a small group of local climbers who shared the ultimate dream of climbing El Capitan and the Diamond. After flunking out of school in 1966, Logan worked as a carpenter, making just enough money to climb and get to the Valley every few months.

The time was a climbing heyday for Logan, bouncing between big faces in Colorado and Yosemite. In summer 1967 in the Valley, she ran into Royal Robbins, who was showing off the newfangled passive protection he had brought back from England. “Nuts probably changed climbing in America more than anything,” Logan says, “because right away we knew that pitons were done.”

Throughout that time, Logan remained confused about “the gender stuff.” All she knew is that she loved to wear women’s clothes—and that she was terribly embarrassed about it. She can remember wanting to dress in women’s clothes ever since age 12 or 13; Logan had read an article about someone who changed gender and was intrigued by it. When Logan was living in Camp 4 in 1967–’68, there were no women around—only a bunch of macho guys. And so she kept her desire secret. “It made me feel screwed up and weird,” she says, “like there was something wrong with me. Why do I do this?” She had clues that there were people like her, but for her it didn’t seem possible. Instead, she snuck around and wore women’s clothes in secret, thinking that if anybody found out, her life would be over. Even worse, she feared that nobody would want to climb with her again.

It all came crashing down at the end of 1968. Logan got drafted and sent to Vietnam, where she served from 1969 to 1970 in an area behind the front that was hit by rockets every night. “When they let me out in the spring of 1970, I went straight to the Valley and up on a wall with Goss, my best climbing partner,” Logan says. “We were up eight or 10 pitches on this new route on the Captain, and I just started crying. I said, ‘I don’t want to be here. I want to go down.’ I was an emotional wreck.” The strain of living, the aftermath of Vietnam, and the stress of climbing hard way off the ground crushed Logan. It would take her more than a year to get back on the sharp end. “Time passed, I went climbing, it got better,” Logan recalls.

In summer 1976, Logan and Goss made a longtime dream come true when they nabbed the first free ascent of the Diamond. Before their ascent, the Diamond had never been climbed without a haulbag, bivy gear, or hammer—they climbed with just hexes and nuts. Goss led the last pitch, a vertical 5.11 that is the final part of the Black Dagger Chimney, when it started to rain. With no bivy gear, their best option was going up. Goss put chalk on his shirt to clean the holds and fired the crux. “Then I came along and it hit me that I only had to climb 10 feet of this just-off-vertical, technical, crimpy thing and we’ll have done the first free ascent of the Diamond,” Logan recalls. “We each climbed every pitch and nobody fell. When we made it to the top, we realized that this is how everybody is going to climb this now. It’s going to be just a rock climb. It’s not going to be a big wall anymore.”

They didn’t tell anyone about their ascent, but Logan’s friend and climbing partner Roger Briggs called a few days later.

“Hey, Logan,” Briggs said. “We’re going up to do the first free ascent of the Diamond. You didn’t do it already did you?”

“Yeah, we did, actually,” Logan responded. “I’m sorry, Roger. I feel bad, but we did.”

Logan had gotten married in 1971 and had twin boys in 1972 while working as a carpenter, but in 1975, they divorced. (They would share joint custody.) She funneled her frustration, anger, confusion, and hurt into a four-year climbing rampage during which she sought bigger, more dangerous objectives, like Changabang, Denali, the Hummingbird Ridge on Mt. Logan, and the unclimbed 8,000-foot Emperor Face on Canada’s Mt. Robson.

In 1978, she and Mugs Stump—“This kid who nobody had heard of but turned out to be a pretty good rock climber,” says Logan—ferried loads across a raging river into Robson’s basecamp. Logan had attempted the face in vain in 1976 and ‘77, so this year she and Stump had agreed to spend the whole summer there to reach their goal. “The vision of the greatest unclimbed face I had ever seen remained implanted in my mind,” Logan wrote in Climbing no. 52. They messed around on the lower face, coming out every few days to resupply and recover. After about four weeks, a big snowstorm hit the range, covering the face in rime. The duo saw this as the perfect opportunity, and cast off with 25 pitons and eight days of food. After bivying low, the duo climbed 2,000 feet of moderate ice before roping up for a short rock band. What followed was several pitches of gullies of steep ice and a bivouac. The morning brought challenging mixed terrain for hundreds of feet, and an uncomfortable bivy seat chopped into vertical ice. It snowed most of the night while they sat upright and tried to rest. The next pitch was the crux: 150 feet of overhanging ice and rock.

As she finished her epic six-hour lead, recalls Logan, “There was a point where I was 30 or 40 feet above a knifeblade, and I stuck my bamboo ice axe onto a little shelf and got it to stick, and got it to stick, and got it to stick, and finally committed to it even though I didn’t know what it was stuck in. I pulled as hard as I could and thought, ‘Here I go …. ’” Logan manteled onto the ax and stood on a shelf; she slammed in two pins and equalized them with a red sling as a belay anchor. Says Logan, “When I did that section, I knew if I fell, I would kill me and Mugs. Steve House went back 30 years later thinking he was doing a new route. He pulled onto the shelf to find two pitons and a bleached-white sling.” House later graded the free version of the pitch M8. (Logan began on aid before switching to free climbing.)

Stump quickly jumared the crux and then led the last four pitches of snowy slab to the summit ridge, where they spent the night. After 28 pitches of difficult climbing, they decided to forego the summit (Logan had summited on a previous trip) and downclimbed the South Face without a rope.

With two 5-year-olds at home and the knowledge that this type of climbing would eventually kill her, Logan swore off hard, scary ascents. She remarried and went back to school in her thirties to become an architect. Work flooded in, and a friend introduced her to sport climbing in the mid-1990s. “Then it was all over,” Logan recalls with a smile.

The ease of clipping bolts fit well into Logan’s family life. She was able to reach her goal of climbing 5.13. In 2007 at age 61, she ticked Sonic Youth, a 5.13a in Clear Creek Canyon—it was among a half-dozen 5.13s she did in her sixties. (Ironically, she’d made the first ascent of the line, on aid, in 1966.) But her secret longing to wear women’s clothes was always right under the surface. At age 50, she told her wife, who agreed to her wearing them around the house. However, Logan still didn’t want her teenage kids to know, for fear of “screwing them up.” She began to dress as a woman more often, driving her car to distant gas stations where she wouldn’t run into anyone. Around the same time, the Internet was on the rise, and she realized that gender confusion is more common than she thought and that there were other people like her.

When her kids left the house in 1997, the American Alpine Club (AAC) asked her to be on its board. With an annual meeting in Seattle, Logan saw a new city as a chance to dress as she pleased. Before the AAC events started, she sought help presenting as a woman for a few days. “A very sweet woman helped me get dressed up. We went to JC Penney’s and bought clothes, then went to a restaurant,” Logan says. “I thought, ‘I really like this …. ’ But then, I went to the American Alpine Club meeting the next day [dressed as a man].”

When Logan came back to Boulder, she began therapy to address her gender confusion. With no idea where it might lead or what it meant, the idea of living as a female was attractive but seemed unreachable. “I thought the climbing community would not be OK with this,” Logan says. “[The community] always felt pretty homophobic, with certain magazine articles and route names.” Logan also worried she might lose architecture work because of prejudices against trans people.

In 2014, Logan decided to have her facial hair removed by electrolysis. The next year, she went to New York and dressed as a female for three or four days straight. “At some point it became clear to me that that’s how I wanted to live,” Logan says. She told her kids. “My son Michael said, ‘Oh, Dad, that must have been so horrible to live your life with this kind of secret.’ It pretty much was.”

Over the next few months, she told a few of her climbing partners, and it spread quickly throughout the climbing community in Boulder, where Logan has now lived for more than 50 years. The first question she was asked by a well-known male climber was, “Who do you want to have sex with?” When Logan responded, “My wife,” the climber was befuddled. “But, ultimately, whenever some bigger segment of my world knew, my life got better, and I was happier,” she says. After years of individual and couples therapy, Logan and her wife worked through the emotional turmoil brought on by the transition. They decided to stay married, and are still going strong today.

This July, I went out to Upper Dream Canyon near Boulder with Jamie Logan to see how her life has changed. At 70, she moved through techy 5.11+ cruxes with confidence and ease. Although her life has shifted drastically, Logan’s affinity for climbing has remained a constant.

Interview

Climbing: When you look back on those bold ascents of the past, does it feel like that was a different person?

Logan: When I was climbing, I was climbing. There was no gender stuff; there was just the next pitch. When you’re on something hard and scary, there’s a rule—you gotta take your pitch. You think, “How hard is it going to be? Is there going to be protection? What am I going to do up there?” And gender doesn’t make any difference. When I was climbing, I was just climbing. It was the rest of my life that was confusing.

Climbing: What role does fear play in your life as a climber and transgender person?

Logan: To me, fear in climbing comes only abstractly, when you’re sitting at the base of the route and you’re scared. You think, “Oh, should I go up on this? If I do it, we could die.” I had a good brain for that stuff. When I found myself committed to a big route and runout above bad gear, my brain got really quiet. I can climb better than I’ve ever climbed when I’m 30 feet above a knifeblade. It just happens, and I’m not aware of the rope or how long the fall would be.

However, transitioning was terrifying. It was way scarier than the Emperor Face: What if I can’t climb with anybody? What if I screw up my kids? What if my wife divorces me?

Climbing: Any negative experiences in the climbing community as a transgender person?

Logan: No, not really. [When I came out], I didn’t really know what was going to happen, but I can say that the climbing community—the younger ones in particular—has been incredibly supportive. I think some of the older ones don’t understand or can’t really handle it. There are some people who I climbed with in the 1960s who I don’t see anymore, and I think that’s because of how I live now. It’s, like, befuddling to them. They’re very macho guys. I think giving up all the male privilege—the whole thing is beyond them. I have more architecture work than I can do. Overall, nobody seems to care.

I have this idea that if you’re trans or gay or whatever, if you can look other people in the eye and smile, you’re good. That’s mostly what other humans want. When I’m walking around the grocery store and a woman smiles at me, I have no idea whether she’s smiling because she sees me as a woman or because she sees me as wanting to be a woman. I’ll never know, and it doesn’t make any difference.

Climbing: Has your transitioning affected your climbing?

Logan: My climbing is going downhill, but it doesn’t have anything to do with taking hormones or transitioning—it has to do with the fact that I’m 70! And I feel pretty good that I can still climb 5.12 here and there. I was able to get on a 5.11+ in Boulder Canyon and try hard and even climb above the bolt a bit. I still love climbing, and my goal is just to keep climbing. There’s a gazillion beautiful easy climbs. In Yosemite, I’ve never done Snake Dike and Royal Arches; I’ve never done the Durrance Route on Devils Tower, never climbed High Exposure in the Gunks. I don’t really have to do the hard stuff anymore.

Climbing: Tell me about the process of transitioning.

Logan: It was just a series of steps, like a climb. You do the next move: “I’m going to get rid of my beard, then I’m going to go to New York and present as a female and see what happens. Finally, I’m going to go as a board member to the AAC annual dinner wearing a dress.” That was scary, but the general reaction was fine. I bought a table and loaded it up with my crew, so I had my posse. Like, “Yeah, fuck you. I may be old and wearing a dress, but you don’t get to sit next to Tommy [Caldwell].” I was afraid, and wasn’t able to just be myself. Now I’ve learned how to be myself, but of course, sometimes I feel a little uncomfortable or insecure.

Climbing: How would you describe your life now?

Logan: I feel happy. Even when I started trying to figure this out, there were all these times when I would look in the closet and see my wife’s clothes, and think, “Oh, I wish I could wear that.” Now I can, so it feels freer. It feels like I’m truer to myself.

Climbing: How would you explain this to those who might not understand?

Logan: The whole boy/girl dichotomy is really false. A lot of people live in the gender spectrum, and there’s a lot of in between. There are people who are way boyish of girl, and I’m way girlish of boy. But we all navigate somewhere in this Neverland. I’ll never have the experiences that a young woman did, and that’s fine. Sometimes when I’m on jobsites and I’m explaining how I want the concrete done, I get pretty boyish. But then again, when I arrive on a jobsite carrying something heavy, the Mexican concrete guys will run over and carry it for me. It’s part of their culture. Or when I’m in a meeting at work and it’s busy, people will slip back into saying “he.” I don’t get upset, and I don’t expect people to gender-parse their stuff when all we really care about is [getting the work done].

I enjoy women. I like to wear women’s clothes. I like to not be macho. I like to be more sensitive. I like to be more caring about other people. Those are all things I didn’t do as well when I was a boy. I was always trying to prove myself, like, always working the conversation around to my climbing accomplishments. I like the way women are, and it’s something I have to try really hard to be.

Jamie Logan: A Life on the Walls

- 1966: First free ascent of the sandbagged Crack of Fear (5.10d), Twin Owls, Lumpy Ridge, Colorado. As Logan wrote on Mountain Project, “When we did the first free ascent in 1966, 5.10 was the hardest grade .… T2 was 5.9 and the Grand Giraffe was 5.8.” Logan concedes that today she’d rate the route 5.11c.

- 1967: Climbed Eldo’s Grand Giraffe (5.10a) with Royal Robbins in the first use of passive pro in Colorado.

- 1972: First ascent of Goss-Logan (V 5.11- R; later freed by Jimmy Dunn) on the North Chasm View Wall, Black Canyon of the Gunnison.

- 1972: Second American ascent of the Eiger Nordwand.

- 1976: FFA of the Diamond, Longs Peak, with Wayne Goss, freeing up to 5.11 without pitons or bivy gear and linking D7 into Forrest Finish.

- 1978: Alpine-style attempt on Changabang’s Southwest Ridge with Dakers Gowans. Every time they climbed above 18,000 feet, Gowans experienced altitude sickness.

- 1977: Attempt on Hummingbird Ridge, Mt. Logan, with Mugs Stump, Randy Trover, and Barry Sparks. “We climbed from dawn to last light every day for weeks,” recalls Logan, “until it became apparent that whole sections of the route were gone.”

- 1978: First ascent of the 8,000-foot Emperor Face of Mt. Robson, Canadian Rockies, with Stump. Logan spent six hours on the crux lead.

- 2007: Redpoint of Sonic Youth (5.13a), Clear Creek Canyon, CO. Logan had made the FA in 1966 with soft-iron pitons, aiders with metal rungs, and a geology hammer.

- 2008: Designs Movement Boulder and then Movement Denver, two influential Colorado mega-gyms.

Julie Ellison was Climbing’s editor at large. This story was first published in 2017.