"You Feel Hunted in the Alpine": An Interview With Jim Bridwell, Climbing Legend

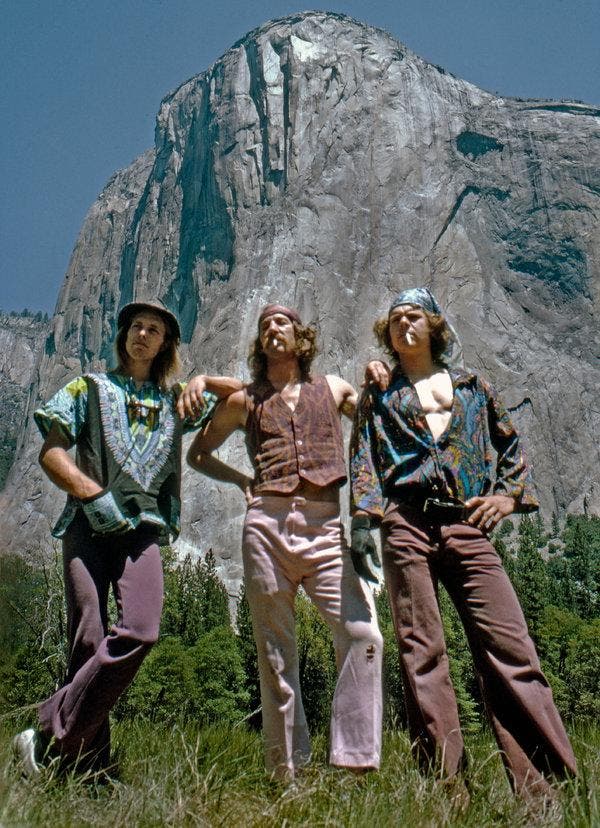

Billy Westbay, Bridwell, and John Long after the first one-day ascent of El Capitan's Nose, 1975. (Photo: Billy Westbay Collection)

This article featuring Jim Bridwell was first published in Rock and Ice No. 61 (May/June 1994).

His morning ritual is complete: a cup of strong, black coffee and a cigarette by the half-open window. He writes, sometimes calligraphically, and these days a cassette of flamenco guitar accompanies him everywhere. Jim Bridwell is a climber who has nothing left to prove.

Yosemite climbers long held their valley up before the rest of the world as the crucible in which one was to be tested. In the late 1960s and early ’70s, they were young, brash, talented, and hungry. With his long hair and mustache, fast-driving, and the passion to train hard and climb harder, Bridwell became the archetypal Yosemite climber.

In the mid ’70s, Bridwell and his partners proved to his generation what could be done with that training and desire. They did the first one-day ascent of the Nose (34 pitches) and the first ascent of the Pacific Ocean Wall route on El Cap (5.9 A5) back to back. When Bridwell, John Long, and Billy Westbay were photographed beneath the Nose after their one-day ascent, they dressed in flamboyant Jimi Hendrix style and seemed to pose the question, “Are you experienced?”

The routes and walls and mountains Bridwell has climbed are too numerous to list: Sea of Dreams, Zenyatta Mendata, Cerro Torre (in a day and a half), the East Face of the Moose’s Tooth, and the Eiger North Face are but a few. His experience on big walls is unmatched. It’s been said that there is no partner you could have on a wall who would improve your chances of success and survival as much as Jim Bridwell. — Steve Dieckhoff

You started climbing in 1962, when you were 18, at a time when very few people climbed. What drew you to the sport?

I was into catching birds of prey, and it was difficult to wait for them to come to you. I’d sit in this blind, trying to hide from their telescopic vision, trying not to move, having all the patience of a normal teenager and getting nowhere. So this became apparent that this was not the way. The way was to climb to the nest and take the young birds, then train them. After a while, the climbing part became more important than the birds.

The social scene attracted me, too. As a child I lived all over the East—my father was in the military, then he became an airline pilot. I went to more schools than years of school. Climbing fulfilled my need for community. And it was one I could fit into—people seemed more intelligent; it wasn’t just the normal high school scene. They were thinking about something other than what kind of car they wanted—except for maybe Galen Rowell, who had a little repair shop. He was a car guy.

Young people often have a sense of immortality. Did climbing shake that sense for you?

I saw immediately how serious climbing could be. You didn’t have the protection you do now. I came close quite early on, on the East Chimney of Rixon’s Pinnacle. The second pitch is 5.8; it’s an overhanging bombay chimney. If you stay on the outside it’s much easier, and you can get protection. But I didn’t know that, and I was cowering in the back. I remember looking down—my last piece was 60 feet below me, and I was running out of strength. I looked to see what I would hit—it was the top of this pillar. I was sure I was headed for this target.

In my second year of climbing I lost a friend, Jim Baldwin—he did the first ascent of the Dihedral Wall on El Cap. He died rappelling off Washington Column, climbing with John Evans. Jim was the first person at Camp 4 to actually call me by name. I wasn’t in the climbing circle—it was a tight clique. People who climbed considered it to be esoteric, and they guarded what they knew pretty carefully. If you really wanted to climb you had to become a member of the clique, and the initial stages were difficult—no one wanted to take you climbing. Jim was the first person to be receptive to me.

How did his death affect you?

I went up on the body carry with the Park Service people. To see the body lying there, with no life in it, just the shell of a person I knew … it really struck home. And there was something else that bothered me. John Evans told how Jim had wanted to come down, that he had a foreboding about the climb. He asked if John would hate him for going down, and John said, “Of course not; if you don’t feel like climbing, we’ll go down.” So Jim rappelled first, and he somehow didn’t take the proper precautions and went off the end of the rope.

You started as a free climber. What’s your most memorable free climb from that era?

Twilight Zone, down by the Cookie. It was one of the hardest climbs around at the time. [It’s now rated 5.10d.] I’d been climbing about two years, so I wasn’t exactly a seasoned veteran. Frank Sacherer led the crux pitch with three pieces, and only the last one was good. I remember watching him above me, wondering if he would fall and pull me off—I was standing on a small ledge with only one poor piton for an anchor.

So that’s what impressed you?

That and the way he did it. It’s a wide crack—3 1/2 to 4 inches. He didn’t climb in the crack; instead, he was back-foot chimneying on the little rugosities on the wall and leading out with crummy protection. It astounded me how far out he’d go, just how much it must have meant to him to succeed.

Why did you get into aid climbing?

My sense of adventure, really—there’s always been an element of risk in my background, as far as climbing goes. I wanted to go to the mountains, and I know aid would be good experience, because you’re not always able to free climb there. Back home in San Jose, we’d go out and aid-climb trees. We’d nail pitons into them, then go out the limbs and practice overhangs and sling work.

And I was drawn to the higher walls—I used the short routes to develop the skills I needed to climb major rocks. It was the golden age of big-wall climbing—the only routes on El Cap were the Nose and the Salathé Wall. There’s not much left out there today in terms of new lines—the virgins have all been taken.

You moved rather quickly into free climbing big walls.

Yeah. I always wanted to do things in better style—either faster or with more free climbing. It was always a lot more exciting to do 5.10 1,000 feet off the ground rather than 150 feet. You couldn’t put in much gear, because gear placement took time—even when you were really proficient, it took 45 seconds to a minute per placement. Big walls change your attitude—the trees on the ground look like broccoli; there’s definitely a mental factor. Many people’s boldness goes away, and the aid slings come out.

Was there a turning point for you, when big walls no longer seemed threatening?

A week after I did the first one-day ascent of the Nose, I completed the first ascent of the Pacific Ocean Wall—it was the most difficult route on El Cap at the time. I spent nine days on the wall; it was the first time I was actually living the experience. Before the PO I was into climbing fast; I always felt a little tense. You get the feeling you don’t belong up there—the birds do, but you don’t. After that route, I felt I had done the most difficult thing, and there was no longer any point in being worried.

You feel sort of hunted in the alpine situation. You’re the prey; the mountain is hunting you.

When did you make the transition from big walls to alpinism?

In 1975, the same year I did the one-day Nose ascent; in fact, I did the Nose as a training climb for the mountains. The first place I went was the place that intrigued me the most—Patagonia. In 1963 Chris Fredericks showed me a picture from a ’61 issue of the American Alpine Journal, and said, “This is what climbing’s all about.” And I just went, wow. The wildness of the place—it’s the epitome of climbing.

It took me 12 years to get there—it’s mainly a matter of money, eh? That’s why we don’t have many American alpinists. It’s easier to hang out in Yosemite, where there are lots of great routes. To climb mountains you have to put your nose to the grindstone, which takes away from your climbing training, so it’s sort of self-defeating.

I felt I had already learned a lot in Yosemite, so I got a job on the oil rigs and earned enough to get me down there. I didn’t even have a round-trip ticket—or a partner, as it turned out. I went with Kim Carrigan, but he got deported at the Buenos Aires airport for no passport. I ended up meeting some Australians, and climbed with one of them. We did the first ascents of Mojon Rojo and El Mocho.

How does the mindset/philosophy differ between big walls and alpinism?

You feel sort of hunted in the alpine situation. You’re the prey; the mountain is hunting you. There’s always a sense of urgency—get it done and get out. You’re not up there to play. I had all the skills—I knew there was nothing I couldn’t aid or free climb, if it came to it. I felt confident in the arena, but there was always a very real sense of adventure. You could do 5.7 and still be scared. Technical difficulty had little to do with it.

You mentioned “living the experience” of a big wall when you did the Pacific Ocean Wall. Can you explain what you meant?

Living in a vertical world, day after day, you get used to certain routines. Handing things from one person to another—it’s not just a casual thing, because gravity is always there to wake you up. There are certain things you just don’t drop. You get in the habit of attaching each thing to a sling and clipping it off. And order—you have to know exactly where everything is, so you can find it in the dark if you need to.

How about sleeping on a wall? What are your dreams like?

I seldom have a problem sleeping, although several times I’ve awakened and wondered, where the hell am I? On the Sea of Dreams [El Cap], we talked about our dreams, and some of them were pretty wild, but I don’t remember what they were.

Have you had any falling dreams?

I had one shortly before I did the PO. In my dream I was soloing El Cap. I was on a sloping ledge, and I felt off balance and started falling toward the outside of the ledge. Suddenly I had chalk on my hands, and I was able to stop myself right at the edge.

Then the dream recurred almost immediately. This time I skidded on the ledge for a second and went off, plummeting toward the ground. I spread my arms, and instead of falling I soared through the Valley, just like a bird. It turned into a wonderful flying dream.

But the bizarre thing is what happened on the PO. I had just followed the third- or fourth-pitch-to-last pitch; it was getting late, and I was looking for a bivi. There was an easy ledge, and I untied from the rope and walked across. It was just like my dream, a sloping ledge, and I was untied. I was very, very careful.

Does it feel weird to get off a wall after you’ve been on one for days?

It does. You step from a vertical world into a horizontal one, and sometimes your balance isn’t as good as you thought. It’s because you’ve developed a whole different sense of living, like a big-wall animal, a new creature.

Did you manage to keep a social life going with your focus on alpinism and Yosemite?

You mean girls? I believe I had a bit of a reputation, which is pretty well documented in other places. It is hard when I go off for months at a time. I’ve been married since 1980; I met Peggy about a year before my first Patagonia trip. I was gone for three months; then I went straight to the California Sierra to teach a mountain-rescue seminar. Peggy paid a friend to fly her to Bishop and pick me up. Pretty romantic, huh?

Do you have any children?

We have a boy, Layton, who’s 14. He doesn’t climb; he’s a very talented artist; he’s in the specially gifted group. He gets nearly straight A’s—sometimes I think, where does that kid come from? Though I was into art when I was young and had stuff at the state fair.

Do you still climb big walls or pursue alpinism?

I did a new route on Half Dome in 1990—Shadows. But there’s not much left to do, and my interest is in new routes. If I climb an existing route, it’s to guide it. I climbed the Eiger in 1992, but I haven’t had much time for alpinism. I was the head rigger for Cliffhanger; that took all my time for a while. Most of the work took place preproduction: ordering all the equipment, setting up the stuff for the climbing stunts, scoping out the camera positions and platforms, cleaning loose rock, helping the special-effects staff rig their stuff. Rigging is a good business—there’s a lot of it going on in the LA area, so it keeps me busy.

How about sport climbing?

It’s fun. Sport climbing is a lot like sport fucking—a lot of fun and not much commitment. There’s a little granite area I developed this winter, just outside of Palm Springs in the San Jacinto. A private place for me and my friends. I’ve put in 19 routes, from 11a to 12c.

You’re 49. At what age do you think you were in your climbing prime?

Technique-wise, I’m climbing as well, if not better, than ever—after a while you know how to do it. But I’m not as strong as I was. I think that could be a training thing—I don’t have time to train the way I used to. I have a family, and jobs that take me away. Before I was totally dedicated to it.

How has climbing shaped your philosophies?

A lot of things people consider really important—their annual income, a Ferrari in the driveway—are not important to me. How I gauge success is different from others. I’m not willing to sacrifice my life for objects. I want to dedicate my life to experiences, character, spiritualism—I consider these better things to waste your time on. Although there’s something to be said for mowing the lawn.

Marjorie McCloy was the Editor of Rock and Ice.