The Big Maybe—Revisiting David Roberts' The Mountain of My Fear

David Roberts on the summit of Denali in 1963 after forging a direct line up the massive Wickersham Wall. (Photo: David Roberts Collection)

The first thing I did when I heard that David Roberts had died was read The Mountain of My Fear (TMOMF) again.

I encountered TMOMF in 1976 when my 6th-grade homeroom teacher busted up our bathroom floor hockey game and the punishment was a book report.

Unaccountably, my elementary school library in Plano, Texas was stacked with mountaineering books—Buhl, Bonnington, Brown, Boardman, Harrer, Herzog, and Messner. I read them all. Eventually I worked my way to the Rs and laid my hands on The Mountain of My Fear.

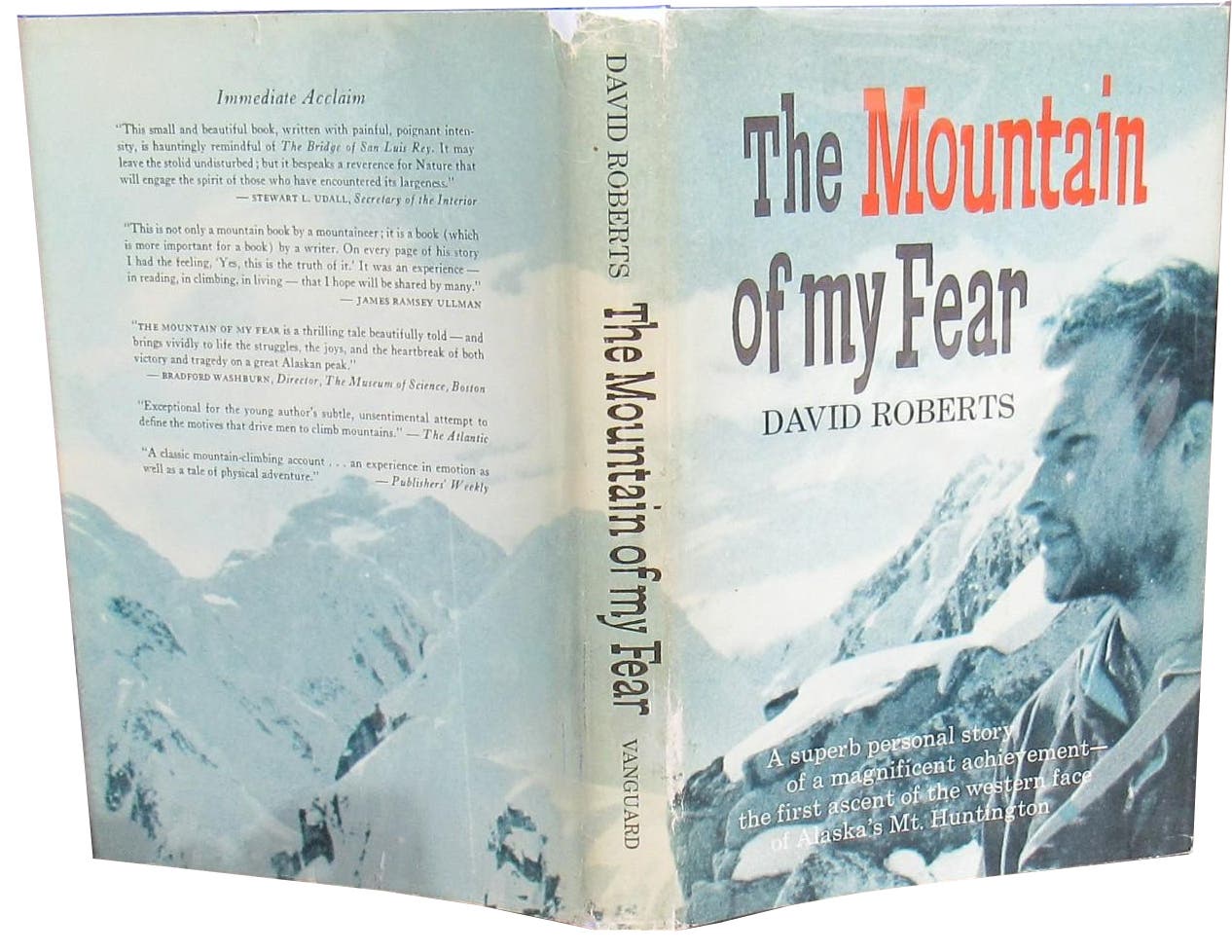

It didn’t take long to see that Roberts was a different caliber of writer. Jon Krakauer—not one to lavish praise—wrote in his foreword to a later edition of TMOMF (the first edition was published in 1968) that Roberts had “certifiable brilliance.” Krakauer runs down Roberts’ cutting-edge first ascents, highlighting his 1965 climb of the west face of Mount Huntington with Matt Hale, Don Jensen and Ed Bernd. TMOMF was based on the Huntington ascent and Krakauer characterizes it as “perhaps [Roberts’] finest” while placing Roberts at the lonely pinnacle of bad-ass climbers who can also write. In fact, Krakauer—author of Into Thin Air, the best-selling climbing book of all time—notes that David Roberts might be the only one.

It’s hard to gauge the significance of Roberts and Company’s Huntington climb from 45+ years away. They must’ve felt a huge sense of adventure when, just in their 20s, they loaded a VW Microbus in Boulder, drove to Alaska and chartered a ski plane to drop them on the Tokositna Glacier with several weeks’ worth of food and 7,000-feet of rope—all of which they fixed.

They basically sieged Huntington in a style that seems quaint (they brought a Monopoly board) and distant from modern fast-and-light, disaster-style alpinism. Roberts, Hale, Jensen, and Bernd took three weeks to climb the 30-pitch Harvard Route. These days, in good conditions, it’s usually done in a day and the current speed record is 14 hours.

Roberts’ climbing style, though cutting edge for the time, is retrograde in TMOMF, but the writing is still fresh. Krakauer states that Roberts’ trademark is “unflinching honesty.” What stands out to me is the energy Roberts puts into chasing down the psychological and philosophical underpinnings of the climbing experience. Other climbers have written about their struggles and triumphs, but Roberts goes deeper, shares his responses on a more intimate level.

This reflection from the summit of Huntington is an example of the way he interrogates and renders experience: “There was little to do, nothing we had the energy for, no gesture appropriate to what we felt we had accomplished: only a numb happiness, almost a languor … If only this moment could last, I thought, if no longer than we do. But I knew even then that we would forget, that someday all I should remember would be the memories themselves, rehearsed like an archaic dance; that I should stare at the pictures and try to get back inside them, reaching out for something that had slipped out of my hands and spilled into the darkness of the past.”

In describing the summit of his finest mountain he traces it back to the transitory nature of experience. This is Roberts’ thing. He wrings beauty out of the fact that nothing lasts. TMOMF is saturated with lines like this.

Here’s another, particularly affecting to read just days after Roberts crossed over: “And that someday I might be so old that all that might pierce my senility would be the vague heartland of something lost and inexplicably sacred, maybe not even the name Huntington meaning anything to me, nor the names of three friends, but only the precious sweetness leaving just a faint taste mingled with the bitter one of dying.”

Roberts, in his preface to TMOMF, dismisses the book—which was drafted in a white-hot nine days—as a “purgative,” to help cope with the loss of Ed Bernd who died on the Huntington descent, and was “written under the influence of a kind of romantic existentialism and in its giddier flights of the prose of Faulkner.”

Agreed. The prose can blush purple, but there’s something so unfiltered and thereby winning about Robert’s great imagination unfettered. TMOMF is Roberts young and unchained, and if the headier tangents are a touch high-flown, they are never windy—always freighted with substance and a fearless commitment to “telling it like it is,” as Krakauer puts it.

Roberts returned again and again to this theme of impermanence, questioning the validity of climbing, working out the balance of risk and reward in his dogged pursuit of the truth. In Moments of Doubt, his most-anthologized essay, Roberts concludes that “it was worth it then.” The “then” suggests that even in 1980 Roberts’ was wavering. In April 2021, just five months before his death, Duane Raleigh interviewed Roberts for Climbing Magazine and Roberts’ equivocates even more.

“25 years later, in my climbing memoir On the Ridge between Life and Death, I came to a quite different answer,” he says. “It took me all those years to realize that in 1980 I had faced the query, ‘Is it worth the risk?,’ only in terms of myself. The ‘yes’ boiled down to a calculation that the joys of climbing outweighed the sorrows. What I hadn’t pondered was the lasting impact of a climbing death on the victim’s loved ones [his friend Gabe Lee died trying to free a stuck rope with Roberts on the First Flatiron outside Boulder in 1961]. In 2004, I looked up Gabe’s brother and sister, whom I hadn’t seen since 1961. Marian, in particular, had nursed a 44-year rage against me, fueled by her incomprehension of what had gone wrong that July day on the First Flatiron. By the end of our marathon encounter and the writing of my book, I was reduced to that tentative ‘Maybe.’ And that’s the conclusion I stick with today.”

I don’t know about you but I think that “maybe” is a disappointingly indefinite conclusion from the guy who might be—by dint of flawless prose and strenuous cogitation—the greatest translator of the subtleties of the climbing experience.

“The quest for a summit was [something I’d give my life for],” he wrote in his recent interview with Climbing. “Youthful obsession is fanatic, and it holds life cheap. But in one’s later years, there’s nothing quite so deeply involving.”

As usual, Roberts sums it up nicely. Alpine climbing is worth it—a fanatic obsession that you’d give your life to—until it isn’t. There’s really no need to judge it on a continuum. Roberts himself calls such judgements “pseudo dilemmas” even while occasionally engaging in them.

The other day while I was taking a rest in the kneebar on my project, I asked professor Neil Stotts, my belayer, if he’d ever read David Roberts.

“Oh yeah,” he said. “I’ve read a ton of Roberts’ books. The Mountain of My Fear and Deborah and On the Ridge Between Life and Death.”

“What do you think of him?”

“He’s one of the best,” Neil said, and the professor has read pretty much every climbing book ever written in English.

We continued our conversation on the hike out.

Neil said, “I love reading David Roberts but he reminds me of those born-again Christians who were into drugs and fighting and partying and sex and everything and then they find Christ and stop all that stuff, but somehow the partying and sinning is all they want to talk about. Of course, David Roberts wrote a ton of books that weren’t about climbing, but when he wrote about climbing he always seemed to revisit the tragedies.”

It’s obvious that Roberts is working something out in the “purgative” TMOMF—something that he’ll continue to process for a long time—and it’s riveting to read. Is climbing worth dying for? Maybe.

Alpine climbing is an act of profound selfishness, but that doesn’t mean it’s necessarily a bad thing to do. Roberts’ The Mountain of My Fear proves these acts of selfishness—these peak experiences—provide you with both moments of doubt and moments of transcendence. The moments of doubt will haunt you and make you wise, and the moments of transcendence will lift you up, and you’ll continue to mine them for meaning, material, maybe even high art like the writings of David Roberts—for the rest of your life.