The Mod Squad

"Mile Mills" (Photo: Mile Mills)

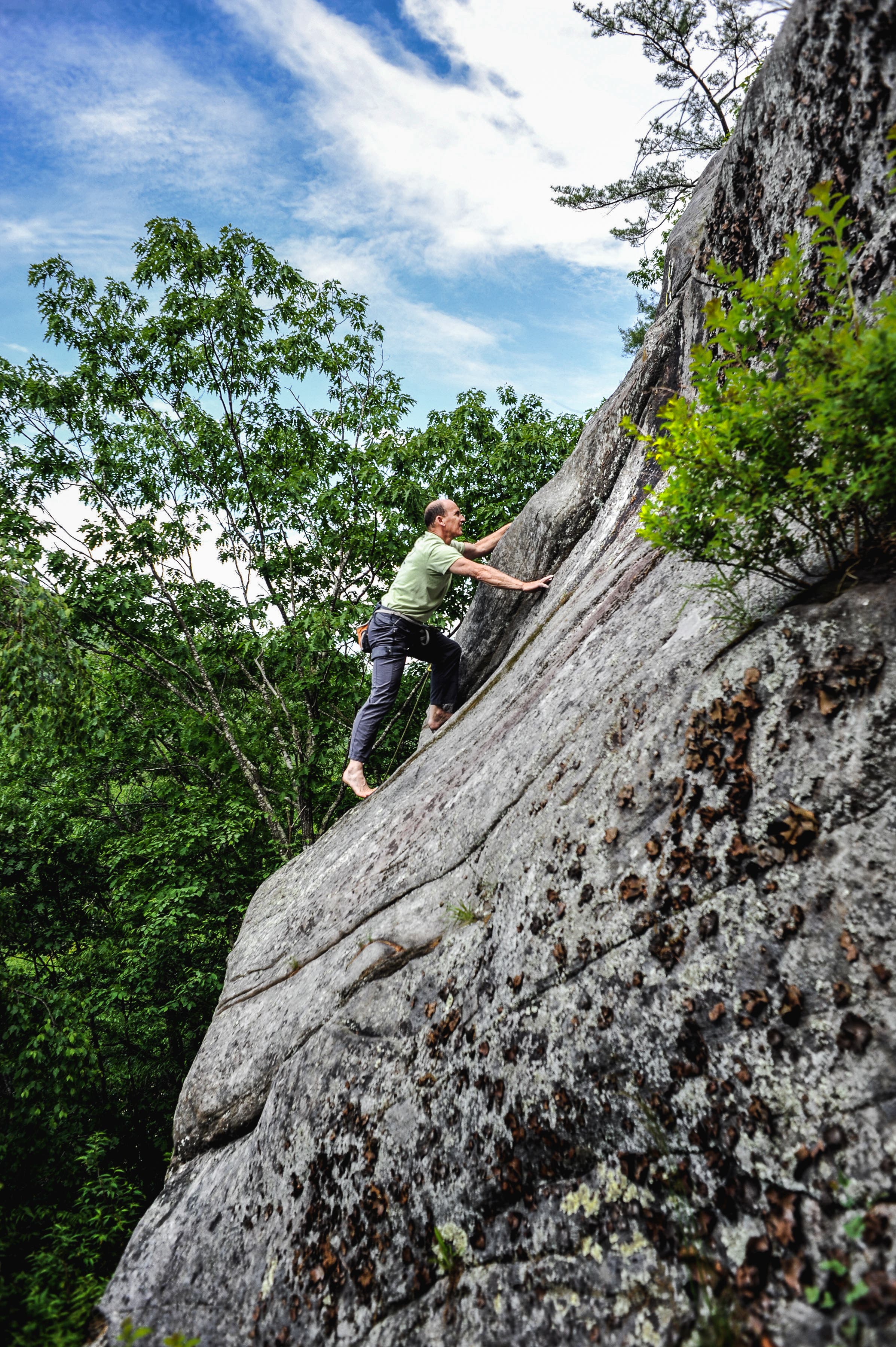

As a climber who doesn’t plan on breaking any records or even leading a 5.12 any time soon, I seek out the 5.10-and-under climbs at my local cliffs. I like climbs that don’t make me contemplate my mortality on every move, as I suspect most of us do as well. Still, the media so often focuses on the climbers ticking 5.15s—the Adam Ondras and Margo Hayeses—when so few of us attain these grades. Perhaps the climbers who make it possible for us to enjoy mellower climbs—our favorite 5.8, 5.9, and 5.10 sport routes—also deserve credit.

It’s not just me who loves these easier climbs. Think about your local crag or gym, and how crowded the moderates are compared to the 5.11-and-up routes. According to a recent survey by the Climbing Wall Association, the University of Utah, and Clemson University, 39 percent of us max out at 5.11 indoors, while the majority of climbers said 5.9 or 5.8 was the lower end of their preferred difficulty indoors. (In contrast, 24 percent of respondents marked 5.12 as their preferred upper grade, and only five percent said 5.13 or higher.) We can easily see this preference on rock, too. At Smith Rock, Oregon, the three-star 5 Gallon Buckets (5.8) has over 2,500 ticks on Mountain Project, while the nearby four-star Kings of Rap (5.12d) has only 30.

Even if moderate climbing is not your jam, you’re likely getting on these climbs as warm-ups or using them to mentor newer climbers. However, unless you scour the first-ascentionist names in guidebooks or on Mountain Project, the folks putting their time, money, and effort into bolting moderate sport climbs go largely uncelebrated—despite the fact that their routes see exponentially more traffic than the 5.13s, 5.14s, and 5.15s.

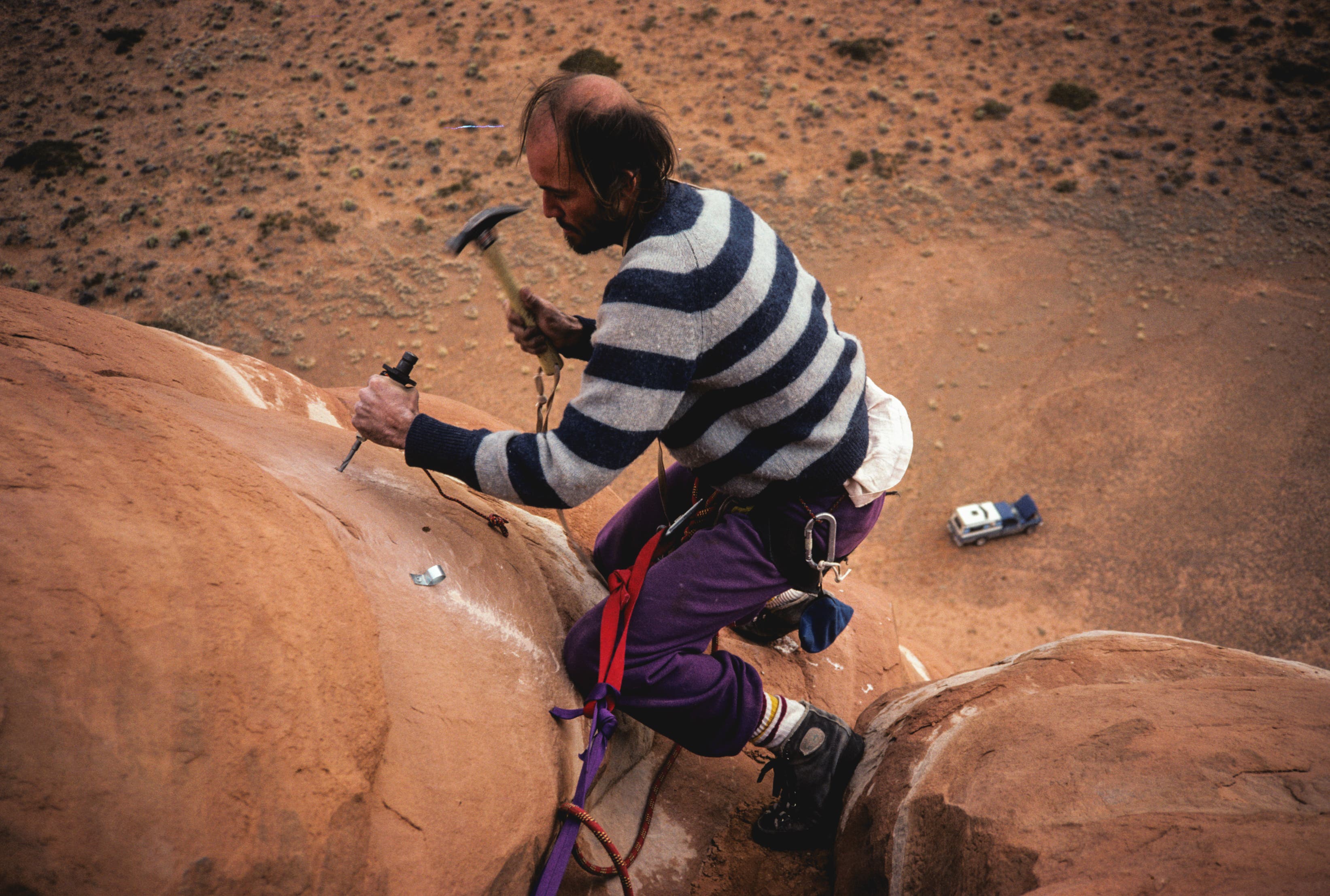

In the early 1980s, America’s first sport routes generally followed more difficult lines that were otherwise unprotectable—and were sparsely bolted, as with the mere six bolts in 75 feet on Alan Watts’s Watts Tots (5.12b; Smith Rock) or the same number of bolts Christian Griffith placed in 1985 on Eldorado Canyon’s first rappel-bolted climb, Paris Girl (5.13a R), which is 115 feet long. At the time, climbers only had hand drills, so first ascentionists would bolt only where they felt was necessary, mainly because it took so long to drill (Watts says often an hour per bolt). On easier terrain, early face climbs ended up being more runout yet—often climbing ground-up, climbers would either climb as far as they were comfortable or punch it to a logical stance to drill. Imagine a 5.12 climber ground-up bolting a 5.7, placing three or four bolts in 150 feet.

In the late 1980s, the power drill hit the climbing scene. With tons of torque and rechargeable battery packs, these drills made it much easier to bolt (no more destroying your hands by repeatedly hammering a bit into the rock), letting first ascentionists bore holes in seconds and opening up the possibility of establishing multiple new routes in a day. This made sport climbing a less elite, less esoteric pursuit, and soon bolt-only face climbs of all grades began to appear across the country. Concurrent was the growth of gyms, of which there are now 530 and counting in America according to the Climbing Business Journal. With the boom in gyms, which are most new climbers’ intro to the sport and offer fun, juggy moderates, climbers have come to expect this experience outdoors, seeking well-protected introductory leads in the 5.6–5.9 range—climbs that would have been lethally runout three decades ago. And route developers have responded, or perhaps in a chicken-and-egg scenario, the developers who’ve chosen to focus on establishing moderate sport climbs are also creating the demand.

This moderate boom has its pros and cons. On one hand, the climbing community has become more inclusive—you don’t have to be a 5.11 trad leader or a 5.13 sport climber to go rock climbing anymore. On the other hand, more people cause more impact. Kenny Parker, the vice president of the New River Alliance of Climbers (NRAC), has seen the increase in impact at his home cliffs in West Virginia, including overcrowded parking lots, lines for popular climbs, and erosion on approach trails. He says that while the NRAC has contributed to building and fixing trails and improving parking and access, their big focus recently has been on stewardship education. In an email, Parker wrote: “Climbers aren’t the same people as when I began climbing in 1985, and we have to adapt to who these people are now and not totally expect them to know how to behave in these outdoor environments.”

After talking to the following nine first ascentionists—all of them responsible for scads of new, moderate sport climbs across America—I learned that putting up these moderates often takes more work than establishing more difficult climbs, usually because of the broken-up, slabbier terrain, sometimes covered in loose dirt and lichen. The climbs can involve hours of cleaning off moss, loose rock, etc., as well as making sure each bolt is strategically placed. While each developer had a different philosophy about route-smithing, all stressed the importance of taking the time to make sure each climb is as good as it can be. While many have also established 5.12s and 5.13s, they say they mostly just like establishing new lines regardless of difficulty; they bolt routes for the adventure of exploring new rock and for the community aspect of sharing that resource. Many of these longtime equippers have also become leaders in their communities, serving as stewards, role models, and mentors.

Here, we present the “Mod Squad,” nine American climbers who’ve each put up anywhere from 50 to over 500 (yes, 500) climbs at their local areas.

Jared & Karla Hancock

Location: Traveler’s Rest, South Carolina

Age: Jared: 46; Karla: 38

Number of Established Moderate Routes: Jared: 200+; Karla: 60

Estimated Number of Bolts Drilled: Jared: 2,000; Karla: 600

Estimated amount spent on bolts & drilling equipment: Combined, around $10,000 during their bolting heyday of 2004–2006

Favorite First-Ascent Names: Gettin’ Lucky in Kentucky (5.10b), Tectonic Wall, Muir Valley; Bitter Ray of Sunshine (5.10b), Great Wall, Muir Valley

Recommended Moderate Area: Tectonic Wall, Muir Valley, Kentucky

Jared Hancock proposed to Karla, now his wife of 13 years, while bolting a route in Muir Valley in March 2005. Recalls Jared, “I found this one [route] that I thought was really pretty, so I rappelled in and put some anchors, and then hung the engagement ring [at the chains].” As Karla toproped the line, inspecting for potential bolt placements, she took three falls and asked to be lowered. But Jared wouldn’t let her. Then she saw the ring. “After I lowered her to the ground, she was still smiling,” says Jared. Karla accepted, then went on to finish bolting the route and made the first ascent. “I thought she should have named it something appropriate, like The Proposal or The Engagement, but she chose Posse Whipped,” Jared says.

The couple started putting up new routes at the Red in 2004 when Rick and Liz Weber (the owners of Muir Valley) invited them to bolt on their property. From 2004 through 2006, the Hancocks put up a combined 200 to 300 routes, with the majority being sport routes in the 5.8–5.10 range—standout Muir Valley classics include Gettin’ Lucky in Kentucky (5.10b) and Send Me on My Way (5.9-). While the couple also put up some 5.11s and 5.12s, Jared found more people climbed and enjoyed the moderates, so he focused on that range. For him, the grade matters less than the simple act of exploring and discovering “what is around the next corner.”

During their years at the Red River Gorge, Karla learned a number of bolting hacks. For one, she started wearing a plastic poncho whenever she gave Jared a backup belay while he was cleaning a route to avoid getting covered in the lichen and dirt showering down. Karla also bought a book about snakes so she could identify the serpents they kept seeing in Muir Valley. “It’s very common for me to take a nap at the base of a cliff in the sunshine and wake up to a copperhead coiled right next to me,” Karla says.

Now, Jared is a full-time route-setter at Climb at Blue Ridge in South Carolina, and Karla is a regulatory compliance specialist in construction and engineering. Karla also sets at the Blue Ridge gym, coaches the youth climbing team, and, she says, acts “like an Uber” for the couple’s eight-year-old daughter, Lucy. Lucy topropes 5.11s and 5.12s outside and does gymnastics, swimming, whitewater kayaking, and mountain biking. This past year, the couple took their daughter to the Red for her first lead: Plate Tectonics (5.10a)—which the pair helped establish with the Webers in 2005.

Todd Gordon

Location: Joshua Tree, California

Age: 65

Number of Established Moderate Routes: “Way more than I ever want to be put in print.”

Estimated Number of Bolts Drilled: Prefer not to say

Estimated amount spent on bolts & drilling equipment: Prefer not to say

Favorite First-Ascent Name: Lubricated Goat (5.10), Escape Rock, Joshua Tree

Recommended Moderate Area: Siberia, Joshua Tree

Some call Todd Gordon the “Climbing Mayor of Joshua Tree” because of his many contributions to and positive presence in the park, whether it’s his untold first ascents or his onetime informal climber hostel, the Gordon Ranch, which provided a home to wayward climbers from 1985 through 2002. The now-retired schoolteacher has been climbing since 1972 and is the author of the guidebook Joshua Tree Sport Climb & Top Rope Sites, which was published last year.

Gordon has been climbing in Joshua Tree since before it became a national park in 1994, and you’ll find his name attached to the first ascent of many bona fide classics, including Sexy Grandma (5.9 mixed), Lubricated Goat (5.10), and Dos Chi Chis (5.10a). When Gordon started putting up routes in the 1970s, they were primarily traditional climbs, and he took a conservative approach to bolting when it was needed. Says Gordon, you’d “climb until you were so scared you couldn’t climb anymore, and then you just stood there and hand-drilled the bolt, and then you climbed again as high as you possibly could go […].” Because of this style, many of his old routes are runout, including infamously scary climbs like Manly Dike (5.10a PG-13) and Bish (5.8+).

Gordon says he established routes because there weren’t many around when he started, and because he liked the adventure and creativity. Over the years, he’s seen the many controversies over different bolting styles erupt, including the bolt wars of the 1980s when sport routes at J-Tree were sometimes defaced or chopped. Within the national park, bolting has also become much more regulated (you need to have a permit to bolt or rebolt in many areas). While this has helped mitigate impact, it can be challenging to navigate. “Any time you drill one bolt, there’s somebody in the world that’s going to be really pissed,” Gordon says.

While he no longer puts up new climbs, Gordon still climbs two to four times a week and, with his wife, Andrea, runs an Airbnb in Joshua Tree. The site gives the Gordons’ digs 4.93 stars, and is filled with reviews from people talking about the “outstanding hospitality,” including Gordon’s willingness to loan guests guidebooks and suggest good climbs.

Lance Hadfield

Location: Albuquerque, New Mexico

Age: 53

Number of Established Moderate Routes: 150–225

Estimated Number of Bolts Drilled: 1,200

Estimated amount spent on bolts & drilling equipment: About $8,000

Favorite First-Ascent Name: Circus Dog (5.11b), Crow Feather Wall, Mud Mountain, New Mexico

Recommended Moderate Area: Luna Park, Red Rock Arroyo, New Mexico

As a kid growing up in Boise, Idaho, and Albuquerque, New Mexico, Lance Hadfield would climb anything he could, scampering around on rocks, trees, and houses. When he was 16, college students in Boise took him to a quarry just above town. Recalls Hadfield, “I was scrambling around over two rocks and came on top of a boulder, and watched these two guys climbing what looked like a blank face. And I sat there for over an hour just watching these two gentlemen climbing and was completely enamored by it. And that was it.”

Hadfield became “obsessed with climbing things that [had] never been climbed,” and by the time he was 19 or 20 had bought a hand drill and was putting up new routes on the granite of the Sandia Mountains above Albuquerque. Today, one driving factor in Hadfield’s thirst for new climbs is simply that he’s already climbed all the routes in New Mexico he’s able to. Thus, when he finds a new area, he bolts whatever routes are there regardless of the grade.

In the early 2000s, Hadfield and his wife, Sarah Brion Hadfield, helped discover and develop a climbing area in southern New Mexico called the Bat Cave. The cliffs surround an abandoned mine, which was “like the Wild West” when they first started climbing there. One Friday night, the couple drove in to see a light shining atop the dark cliff, 100 feet up. When they hiked up the next morning to assess possible routes, they found an abandoned shelter with empty TNT boxes outside and bedding and clothes inside.

Since then, the area has become a popular sport-climbing hub, with quality routes from 5.7 through 5.14. The group of local developers has also developed a trail system to make navigating the steep approach easier and less prone to erosion.

Hadfield has spent most of his life in Albuquerque, building his life around climbing—he works full-time at Stone Age Climbing Gym as the head setter and climbing coach. He and Sarah head out most weekends to explore new areas or to establish routes. One recent find was Mud Mountain near the town of Truth or Consequences, where the couple established 38 climbs from 5.8 to 5.12, created trails, and wrote detailed directions to the desert-limestone bluffs on Mountain Project.Luna Park, Red Rock Arroyo, New Mexico

Gregory Hand

Location: Golden, Colorado

Age: 70

Number of Established Moderate Routes: Around 500 first ascents total (including moderates)

Estimated Number of Bolts Drilled: 5,000+

Estimated amount spent on bolts & drilling equipment: Prefer not to say

Favorite First-Ascent Name: TOPLOB—Take Only Pictures, Leave Only Bolts (5.11a), Sheep Mountain, Poudre Canyon, Colorado

Recommended Moderate Area: Boulder Canyon (specifically Tese, a 5.10- on the Witches Tower), Colorado

Gregory Hand started climbing 51 years ago at the University of Minnesota when he joined the Minnesota Rovers outdoor club. “I thought, ‘Oh, gee, climbing sounds fun,’” Hand says. “I thought you took, like, a grappling hook and you threw it up on the cliff and then you pulled yourself up.”

In the 1970s, Hand lived in Washington, DC, and climbed at Seneca Rocks, but no one bolted there. After moving to Colorado in 1980, he got into bolting because it offered something new to climb. Hand loved steep climbs, and a few classic Colorado FAs in this vein include Free Willie (5.11a; see opening photo) and Threshold of a Dream (5.11d) at Lower Animal World in Boulder Canyon and Br’er Fox (5.7) on Other Critters in Clear Creek Canyon.

In April 1996, Hand tore his ACL at the base of Lower Animal World while bolting what would become his hardest first ascent, Piles of Trials (5.12b). Hand says, “I was moving my pack and stepped up on a rock, and my ACL exploded!” Instead of going immediately into surgery, he climbed through the season; two weeks later, he sent the climb wearing a big knee brace.

Now 70, Hand climbs around one day a week, cruising up moderates or putting up routes with Paul Heyliger, a professor at Colorado State University, Fort Collins. Due to injuries and aging, Hand now tends to bolt and climb low-angle routes, but still loves “the thrill of searching for something new.” Hand especially likes putting up easily accessible beginner-to-moderate routes for his grandchildren. One area he mentions is East Colfax in Clear Creek Canyon, which, he says, is “so accessible you could take a baby carriage” there. When he found the area, Hand says there were around three routes on the cliff. He quickly added another 20, mostly in the 5.5–5.9 range. Now, “If you go on a weekend, there’ll be 50 people,” he says. “It’s almost as though we’ve created a monster.” He also helped bolt the nearby Safari area, which has routes in the 5.3-to-5.9 range and is also swarmed with beginner climbers and guided groups.

In August 2019, Hand encountered a father taking his two sons (ages five and eight) climbing at East Colfax. After watching a few misstarts and confusion, Hand offered to belay the dad while he set up a toprope for the kids. When the dad got to the top, Hand recommended threading the anchor so he wouldn’t have to go back up to retrieve the quickdraws. The dad had apparently never done that before—he was straight from the gym.

“That gave me a chuckle,” Hand says. “So I told him what to do, lowered him to the ground, and made my exit.” Hand notes that while it’s nice that gyms provide a safe learning environment, people need to be aware of the “difference between gyms and the real world.” In summer 2019, an 18-year-old girl died on one of Hand’s routes, Labby (5.9), at the Other Critters cliff after a miscommunication with her belayer resulted in an 80-foot groundfall from the anchor. Hand says, “Soon after, someone went up to that area and installed Mussy Hooks at all of the anchors to mitigate this problem.”

Now, Hand golfs around five days a week and volunteers as his club’s tournament director. He says golf is similar to climbing in that it’s about personal improvement and slowly getting better scores—just like climbers working up through the grades.

Christopher Smith

Location: Wilmot, New Hampshire

Age: 58

Number of Established Moderate Routes: 30+

Estimated Number of Bolts Drilled: 500–1,000

Estimated amount spent on bolts & drilling equipment: $8,000

Favorite First-Ascent Name: Clip a Dee Doo Dah (5.3; two pitches), Jimmy Cliff, Rumney, New Hampshire

Recommended Moderate Area: Rumney Main Cliff—specifically Rock Du Jours Direct (5.9; 2 pitches)

Christopher Smith was one of the first climbers to “discover” Rumney, New Hampshire. “I had been to Rumney once before sport climbing existed and thought it sucked,” Smith says. “Years later, my wife dragged me there to try the [new] sport climbs. She loved it, and we came back every weekend thereafter.” Today, Smith, the co-president of the Rumney Climbers Association (RCA), is an iconic local who’s put up Rumney classics like Underdog (5.10a), Sweet Polly Purebread (5.10c), and The Vaporizer (5.12a).

Smith has been climbing for 42 years and bolting new routes almost from the start. He began climbing with his older brother, Ward (the same Ward Smith who later wrote one of the Rumney guides), while they were in high school in Wakefield, Rhode Island. On weekends, they’d drive to New Hampshire or the Shawangunks in New York to climb. The brothers still climb together today.

Smith’s favorite part about bolting is selecting a line. “I get to choose the line that other people will climb for who-knows-how-long,” he says. The routes he bolts now at Rumney often take huge amounts of work to clean because they are low-angle and typically inobvious (the obvious lines have mostly been bolted). For example, Lonesome Buffalo (5.8) at the Buffalo Pit took Smith around 40 hours to clean. In three- to four-hour stints over 10 days when the weather was too poor to climb, Smith cleared lichen, dirt-covered ledges, and odd bits of loose rock with a pry bar, hatchet, wire brush, and broom.

In Rumney, Smith used to have a friendly competition with other first ascentionists over who could put up the best easy climb. But, in 2000, after Smith bolted Clip a Dee Doo Dah, a two-pitch 5.3 that gets three stars on mountainproject.com, he says, “Everyone kind of gave up … just cause it’s so easy and so good.” With seven bolts per 150-foot pitch, a friendly angle, clean, grippy rock, and amazing views of the valley, the route has become a beloved moderate masterpiece. It’s one, as Jay Knower wrote on Mountain Project, “5.13 climbers regularly romp up … because the setting is so beautiful”—and has also seen an all-free ascent by a dog, Shyla, wearing a Ruffwear harness.

When Smith bolted Clip a Dee Doo Dah, he had just recovered from Lyme disease. During the year he battled the tick-borne illness, Smith went from redpointing 5.13a to 5.10d. As he puts it, “If I’m ever too weak and I can’t climb Clip a Dee Doo Dah, I’m going to have to give it up.” Until then, though, he hopes to continue climbing the easier routes he’s established.

Ryan Cafferky

Location: Hood River, Oregon

Age: 43

Number of Established Moderate Routes: 80+

Estimated Number of Bolts Drilled: “In the thousands.”

Estimated amount spent on bolts & drilling equipment: $25,000 over 12 years

Favorite First-Ascent Name: Vombatus ursinus (5.10d), the Wombaty

Recommended Moderate Area: The Marsupials, Smith Rock

Ryan Cafferky’s bolting interest began around age 19, when he read in a friend’s collection of old climbing magazines about climbers putting up new routes. He devoured any book he could find on climbing at the library. Later, Cafferky started bolting after spying potential new routes at Smith Rock, Oregon. “I just thought, ‘Oh I could probably do that,’” says Cafferky. “And just started out like that.”

From 1997 to 2007, Cafferky (often known as Ryan Lawson on Mountain Project; Cafferky changed his name in 2004 for family reasons) established moderate routes all over Smith, including Birds in a Rut (5.7 mixed) on the Wombat and The Outsiders (5.9) on the Morning Glory Wall. His goal was to spread people out. While Cafferky has also established more-difficult climbs like Heresy (5.11c) on Christian Brothers and Blackened (5.11c/d) on Llama Wall, he mostly loves to put up climbs “that take people to a unique place [and] are more of a journey.” The climbs that inspire him are the ones that bring people to a new or underrated area, discovering a diamond in the rough. Some of his favorite FAs at Smith include the five-pitch 5.9 classic Wherever I May Roam and the five-pitch, beginner-friendly 5.7 First Kiss.

Later in his bolting career, Cafferky would often bolt at night to avoid disturbing anyone with drilling noise or dropping rock. On one such nocturnal mission in 2002, Cafferky was out at Lepers Buttress and spotted an enticing chimney below; he rappelled in to explore, finding a large, hidden water groove. Cafferky says, “I just remember laughing and being giddy because I had found such an amazing feature.” The route, now called The Climb, is a 3.4-star 5.12c on Mountain Project.

Today, Cafferky lives on an 80-acre homestead that’s part of a larger off-grid farm where the community maintains its own water and power systems, and produces most of its own food. He also works as an arborist and runs the farm’s sawmill.

Darren Knezek

Location: Provo, Utah

Age: 57

Number of Established Moderate Routes: 250+

Estimated Number of Bolts Drilled: 6,000–7,000

Estimated amount spent on bolts & drilling equipment: “I don’t even want to know. If you figure it out, don’t tell me.”

Favorite First-Ascent Name: Lunatic Fringe (5.10c; 11 pitches so far), the Jobsite, Rock Canyon, Utah

Recommended Moderate Area: Rock Canyon

Darren Knezek owns the climbing shop Mountainworks in Provo, Utah, close to some of the state’s most popular climbing areas, including American Fork and Rock canyons. Knezek also co-wrote the Maple Canyon Climbing Guide Book and contributed to developing classic Utah zones like Maple, Ibex, Rock Canyon, American Fork, and Joe’s Valley.

One weekend in April 1994, Knezek, Jeff Pedersen, and Bill Boyle were driving down from Provo to Ephraim to trade a climbing rope for a set of tires for Pedersen’s car and to check out a potential climbing area the guy with the tires had suggested. That area was a dud, but as they started heading back, Pedersen took out a map, pointed to a random canyon (the guy they’d met had hinted at possible climbing in some of these nearby canyons), and said they should scout it. This was Maple Canyon. When the group first saw Maple, it had a small campsite along a dirt road and only one established climb (the 5.9 Raindrops on Lichen, put up by Jason Stevens). When the trio went back a few days later, they ran into Stevens. The group (including Stevens) scattered around Box Canyon, scrambling to put up new routes. Knezek says, “The very next weekend, one of our friends found Joe’s Valley, and we went there next.”

Knezek started off bolting easier routes to give his climbing partners something to climb at his new areas. The second route Knezek ever bolted was a 5.11b called The Bulge at the Appendage, Rock Canyon. “[I] just noticed a wall and I thought, ‘Man, this is really cool—no one’s ever seen this before,’” he says. At the time, the hardest route Knezek had climbed was a 5.10c, so The Bulge took him four days of projecting to send. While he was projecting that route, he also put up a 5.7, 5.8, and 5.9 next to it for his partners.

In every area that Knezek bolts, he tries to put up a wide range of grades from 5.9 to 5.13a. While Knezek climbs hard, sending 5.12s and 5.13s, he knows climbers value moderate routes, so he puts those up as well—even if they end up being more work to clean. “Typically, lower-angle routes [in the 5.8-to-5.10 range] in Utah can be quite a lot of work to clean,” Knezek says, including removing loose rock from the friable conglomerate, limestone, and quartzite so the climbs become safe.

Knezek has recently been bolting a multi-pitch climb called Lunatic Fringe in Rock Canyon, which he hopes will be 5.10. “I’ve done like 11 pitches, and it’s 10c so far, so hopefully it’ll still be 10c or d by the time I get to the top,” he says—perhaps stretching 25 or 26 pitches from the Jobsite Wall up Squaw Peak.

Kenny Parker

Location: New River Gorge (mostly), West Virginia

Age: 55

Number of Established Moderate Routes: At least 100

Estimated Number of Bolts Drilled: Thousands

Estimated amount spent on bolts & drilling equipment:

“Thousands”—but now mostly provided by the climber nonprofit New River Alliance of Climbers

Favorite First-Ascent Name: Psycho Wrangler (5.12a), Cotton Top, New River Gorge

Recommended Moderate Area: Orange Oswald Wall, Summersville Lake

Kenny Parker started climbing at age 18 while working as a busboy in Charlottesville, Virginia. The cook there took him to the Ravens Roost crag along Blue Ridge Parkway. “Here I am to this day, stuck,” says Parker. “Stuck as a climber.”

When Parker started climbing in the New River Gorge in 1985, the area was largely undeveloped: “There weren’t very many climbers, so you kind of knew everybody. It was pretty much a feeding frenzy as far as new routes go,” he recalls. With many of the climbers around him “in the new-route game,” Parker followed suit, and bolted one of his first routes at the New, Dragon in Your Dreams (5.11c) in 1986, going on to author such area classics as Hazmat (5.11c) on Orange Wall and Psycho Wrangler (5.12a) on Cotton Top. Mostly, Parker will bolt whatever the rock presents, and for the New, that’s primarily been in the 5.10-to-5.12 range given the Nuttall sandstone’s overwhelming verticality. However, he doesn’t shy away from the 5.7s either (although many of them have stayed traditionally protected, as they were put up in the pre-sport era). In 1994, Parker and his climbing and business partner Gene Kistler opened the outdoor shop Water Stone Outdoors in Fayetteville—less than a 10-minute drive from the gorge.

Parker says many of the New’s routes (especially the old trad routes) were named when Mike Williams was creating the 2010 guidebook, simply because the first ascentionists were “long gone and couldn’t be found.” So Williams asked Parker to come up with some names. “Sometimes,” Parker says, “I’ll just pick up a dictionary and find some cool new words”—such as he did for the Sunkist Wall’s Opulence (5.9).

These days, Parker is married, with a six-year-old son. Over the past few years, he’s been doing a lot more rebolting than bolting, a crucial mission at an area that sees 50+ inches per year of rain and at which many of the early climbs still have subpar, 1980s hardware. Parker and a small crew of other rebolting enthusiasts have been upgrading with a mix of glue-ins, “twizzler”-style eye bolts, and Petzl Long Lifes. Parker is also the vice president and anchor-committee chair of the New River Alliance of Climbers (NRAC), which he helped to establish in the 1990s, and works with the nonprofit to help fund his and others’ rebolting efforts. Parker and his crew are planning to rebolt moderate areas in Bubba City, including Sandstonia and Beer Wall, where the climbs typically range from 5.5 to 5.11. Over the years, Parker and others have updated bolts at almost every crag in the New, chipping away at making the gorge’s 3,000-plus climbs safe for generations to come.

Johanna Flashman is a freelance writer chasing good rock and cute dogs aroung the world. She is currently based in Oakland, California. Her work has appeared in Outside and at SELF.com.