The Noob Chronicles: On Failure

"None"

This story originally appeared in the February 2016 issue of our print edition.

For the very first time since I had started to climb two years earlier, I wanted to quit. I chucked my gear in the back of my car, slumped in the front seat, rolled up a smoke, rolled down the window, folded my arms, furrowed my brow, kicked the floorboard, and said, “Fuck this.”

My previous climbing had been all trad and exclusively outside, and I had never, not even once, wanted to stop. Not when I was the weakest one at every crag, on every trip. Not when someone half or twice my age free soloed blithely past me while I pushed my lead limit on the same beginner route. Not when I backed off a lead and lowered, shamefaced, past my own gear. Not when I flailed, thrutched, chuffed, sweated, bled, or even cried.

None of that was anything a beer and a kind word or dirty joke couldn’t fix. I never went to sleep after a day of climbing feeling anything other than certainty that it was all part of the journey, and there was no better way to spend my numbered days. Until now.

I thought of the dirtbag whose day I would make when I gave away the still-shiny rack, the whimsical doormat I would weave out of my rope. What pushed me to this precipice? I had just failed my lead test at the gym. Again.

“You were too tense,” said Jacob.

“That route is really reachy,” said James. “Hard for short people.”

“It’s mental,” said Wally. “It’s in your mind.”

It wasn’t all in my mind. My excuse for struggling to pass my gym lead test was my unconventional climbography. It was backwards. Due to a chance encounter in a campground on what was supposed to be a hiking trip, I stumbled into a community of part- and full-time van-dwelling itinerant climbers.

I guess they saw something in me. Was it the death wish for which I’d been seeking a healthy outlet my whole life? The novelty of teaching a perennially uncoordinated 30-something Jewish girl from Long Island to trad climb? A pair of boobs, however average, in an environment with a far higher-than-average male-to-female ratio? For whatever reason, they took me in, and for the first time ever, anywhere, I felt at home.

I first roped up in Joshua Tree and multi-pitched in Tuolumne Meadows before I set foot in a gym. I possessed a double rack of prodealed Camalots before I tried to get my lead card, but no trad route under 5.10 is as overhanging as the gym 10b. Due to the fascistic “sport climbing is neither” ethos of my mentors, I had never been sport climbing. Though I could scramble fourth class with a beer in my hand and could open that beer with a lighter, I lacked the strength and endurance to climb even 50 slightly overhanging feet. I would routinely fall from the last bolt of the gym lead-test route. To get the card, you had to send.

It wasn’t falling at the last bolt that bothered me. It wasn’t failing in front of my friends, or the guy I was kind-of, sort-of seeing, or the guy I used to kind-of, sort-of see and his new, real girlfriend. It wasn’t even that a bored teenager with a clipboard had become the arbiter of whether or not I would be allowed to lead climb on this particular plastic wall, when what had first drawn me to climbing was the combination of ultimate freedom and total responsibility, the smell and feel of the granite.

It was that taking a climbing test was changing the meaning of climbing, which had become sacred to me. For the very first time, climbing was not about the journey, the moments, the cyclical and sometimes even chaotic nature of progress, the holistic view of success and failure that defined each day on the rock and each trip to the mountains. Taking the test was all destination and no journey.

Climbing outside, I was tested all the time, but I got to decide how I defined success or failure. Climbing outside, these abstractions felt less like a line in the sand, and more like a continuum. For a recovering perfectionist, nerd, and overachiever, this was healing.

Not that I wasn’t used to failing. I spent the first decade of my adulthood pursuing the singular life goal of becoming The Great Essayist of the 21st Century—a goal I have since amended to An Essayist in the 21st Century. I have been told by famous writers and 22-year-old interns alike that I have minimal talent and no control of my tone, that my writing, like my personality, is “funny, but not quite right.” After a decade of often futile literary striving, trad climbing was a perverse sort of relief. Climbing is hard, but it is easier than writing.

“Fail. Fail again. Fail better,” wrote Samuel Beckett.

I failed. I failed again. I failed worse.

“It’s mental,” said Wally. “It’s just in your mind.”

My regular gym buddies patiently tagged out to toprope with me, but the only other member of our rotating gym crew that winter who toproped exclusively was Wally’s eight-year-old kid.

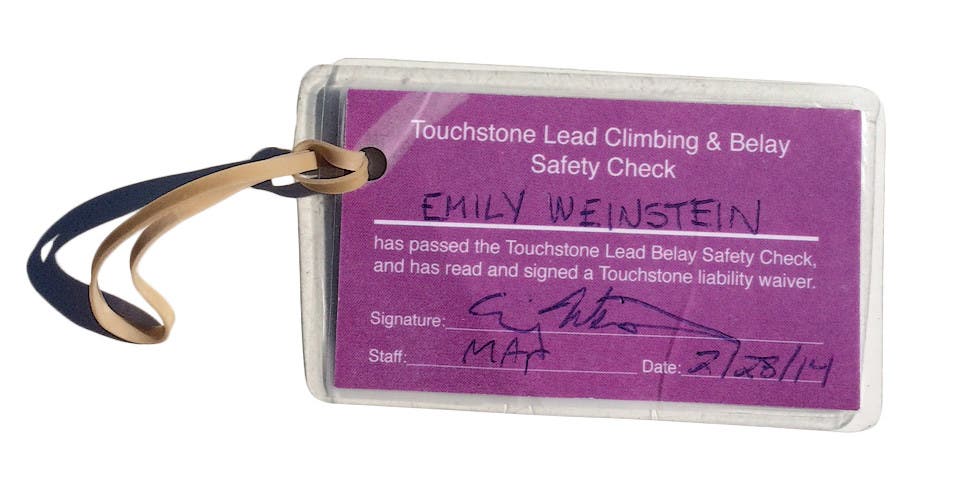

Finally, after a cruel February of useless effort and three humiliating failures, I passed on my fourth try. Jacob reverse-sandbagged me by claiming he really wanted to climb at the one gym in the system where the lead-test route happens to be dead vertical, instead of overhanging. Climbing is definitely about failure, but it is just as much about kindness, patience, and helping out your friends.

I was happy when they gave me the purple card that said I passed my test. I carried it around in my pocket for a while, like it meant something. But then I started dreaming about the next big trip, ogling desert cracks on Mountain Project and wondering what it would feel like to rap off a giant sandstone tower on what looked like a red planet, knowing that all the while, the purple card on its desiccating rubber band would be on the ground in the shredded shopping bag with last week’s sweaty spandex while I would be high above the height of the skylights of any former industrial space full of molded plastic handholds. I’d be signed in to no lead log and released from no liability, and each piece I placed and move I made, each foot of rope I paid out and whip I took would be wholly unsupervised. Out there, each moment would be its own test to pass or fail anew.